“Cool Traditions” Stay in Tune with Modern Life

The World of “Washi”: Paper that Lasts a Thousand Years

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

At the Heart of Traditional Japanese Lifestyles

Paper has been an intimate part of Japanese culture for more than a millennium. Handmade washi paper has a warm texture, as well as a resilience and durability that belie its remarkable thinness. People have cherished and treasured these qualities for centuries.

Washi has been put to an extraordinary range of uses in Japan, not only helping people to meet their basic daily needs but also performing an essential role in rituals. Washi painted with lacquer has been used to make bowls and other utensils, while paper coated with perilla oil was used in traditional parasols and umbrellas. People used to wear raincoats made from a thin and breathable washi fabric called kamiko. Paper lanterns gave illumination at night, while washi fans helped bring relief from the heat and humidity of summer.

Washi was also used for the mizuhiki decorative cords used at weddings, funerals, and other important life events, for the gohei paper streamers used in Shinto shrines and on the altars in people’s homes, and for the white paper used for copying Buddhist sutras and prayers. Papier-mâché Daruma dolls and maneki-neko cats brought good luck and lent an auspicious air of festivity to people’s homes and businesses. Used in the “window” panels of shoji sliding screens, washi filters in soft light into Japanese homes, helping to cultivate a sensitivity to nature and the changing seasons.

Torinoko paper today is used chiefly for Nihonga paintings. A special knife is used to trim the “ears” from the edges of the paper.

Torinoko paper today is used chiefly for Nihonga paintings. A special knife is used to trim the “ears” from the edges of the paper.

In Mino, famous for producing the very finest-quality shoji paper, washi is known to have a slightly beige tinge when new, similar to that of linen. It is only after the paper has been mounted onto its frame and exposed to sunlight for a time that it takes on its beautiful pure white hue for which it is celebrated.

Premodern Edo (now Tokyo) was often besieged by calamitous fires, and many merchants are said to have thrown their ledgers and other important records into a well whenever disaster struck. Once it dries, washi returns to its original state, and letters written in ink are not lost even if the paper gets wet. Washi is also surprisingly resilient to being torn, is repellent to insects, and water resistant. Such adaptability and durability made handmade washi an essential part of daily life in Japan.

Made by Hand, One Sheet at a Time

The secret behind the strength of washi lies in carefully selected raw materials and a painstaking process of hand production that has remained essentially unchanged for centuries.

First, tree bark is boiled. The most widely used species of tree are a type of mulberry known as kōzo, the mitsumata or paper bush, and a shrub called ganpi. After boiling, the outer bark is peeled off and the fibers exposed. The fibers are beaten till soft, then mixed with a starchy binding agent called tororo aoi (also derived from a plant) to make the mash from which the paper is made. The raw ingredients are then sieved and pressed with a bamboo mat called a suki-su and processed into paper, one sheet at a time. The long strands of plant fiber are carefully bound together at this time to make strong paper.

Paper is removed from the suki-su bamboo pressing mat and set aside, one sheet at a time (left). The mash is sieved through the suki-geta frame to obtain paper of a uniform thickness (center). Traditional papermaking is done in the coldest months of the year (right).

Paper is removed from the suki-su bamboo pressing mat and set aside, one sheet at a time (left). The mash is sieved through the suki-geta frame to obtain paper of a uniform thickness (center). Traditional papermaking is done in the coldest months of the year (right).

The same production techniques are used throughout the country, but differences in the hardness of the local water and climate, such as wind, humidity, and temperature, lead to differences in the character and texture of the paper made in each region. A true paper connoisseur in bygone days could reportedly ascertain by sight and touch alone where a particular sheet of paper had been produced.

The technique of making paper by hand is said to have arrived in Japan from China during the first half of the seventh century. It is a method that makes the most of the natural strengths of the raw materials and remains fundamentally unchanged to this day. Yōshi, or “Western paper,” by contrast, is made using machines and chemicals to extract pulp, the color, smoothness, and texture of the paper being determined by the kind of additives used. This makes it possible to achieve higher yields and allows mass production, but the chemicals can easily damage the fibers and make the paper prone to deterioration.

It was only in the second half of the nineteenth century, when yōshi entered Japan, that the term washi began being used to distinguish it from the imported variety. As Japanese lifestyles became increasingly Westernized in the years that followed, handmade washi entered a period of decline as it was replaced for many purposes by cheaper Western paper.

Paper that Lasts a Thousand Years

But some washi varieties have remained alive and well despite the changing times. Indeed, torinoko paper made in the famous washi-producing province of Echizen (in northern Fukui Prefecture) is said to last a thousand years. This may strike many as being a surprising claim, as paper is usually considered to be a fragile thing, prone to tearing if mishandled, turning to mush when wet, and liable to burn if left too close to a source of heat. How can paper be so resilient as to survive a millennium?

A passage in the Wakan sansai zue almanac, published in 1712, refers to torinoko as the “king of papers,” describing it as having “a remarkably smooth surface that makes it perfect for writing and a resilience that gives it a remarkably long life.”

This “king of papers” is a type of washi made from ganpi that is smooth to the touch. In previous times, this durable high-quality paper was particularly esteemed by the nobility and the ruling samurai elite.

Torinoko means “bird child.” What lies behind this curious moniker? Perhaps disappointingly, locals say that there is nothing more to the name than a simple description of its color, which was thought to resemble that of a chicken’s egg. The traditional name has survived, along with the methods by which it is made.

The town of Imadate in Fukui Prefecture is a traditional center of washi production. Situated in a mountain valley alongside a swift-flowing river, it has specialized in making washi for centuries, and numerous workshops still line the banks of the river today.

One of them is operated by Iwama Heizaburō, where skilled artisans produce not only torinoko but also a variety of washi using traditional materials like kōzo and mitsumata.

After many years working together as a team, these workers move in perfect tandem as they lift the freshly made paper, sheet by massive sheet. Cloth is placed between the sheets to make them easier to peel off when dry. The suki-geta used for large sheets like this has to be lifted by crane.

After many years working together as a team, these workers move in perfect tandem as they lift the freshly made paper, sheet by massive sheet. Cloth is placed between the sheets to make them easier to peel off when dry. The suki-geta used for large sheets like this has to be lifted by crane.

During the Edo Period, workshops in Imadate made exclusive, high-quality paper as the purveyors to the shogun and his household. Handmade Imadate washi was also used for banknotes produced by the Meiji government, and later for the 100-yen notes that continued in circulation until the 1940s.

“It’s the combination of soft water and harsh winters that gives Echizen paper its distinctive qualities, says the shop owner. “The best paper can only be made in a place like this, where the traditional environment still survives.” Imadate receives heavy snowfall—up to a meter can fall in a single night. The bitter cold is believed to give the paper its “backbone” and is believed to be essential for making the finest-quality paper. First, the bark is boiled in a large cauldron-like tub, then drenched in cold water. The resulting fibers look like shiny strands of silk. The fibers are washed in cold water, and any extraneous particles or impurities are removed. The fibers are then beaten until they are soft and are mixed with starchy tororo aoi, made from aibika, to produce a mash that is stirred and pressed to produce the paper.

A worker’s well-practiced hands painstakingly remove stray particles or impurities from the plant fibers.

A worker’s well-practiced hands painstakingly remove stray particles or impurities from the plant fibers.

The process of chiri-tori, or removing impurities, is a particularly painstaking stage of the production process. “If you cut corners here, it’s impossible to make good paper,” says one worker. The job of plucking out stray particles and bits of bark that have become mixed with the fibers is performed by veteran workers who know the entire process intimately. They crouch for hours, hunched over their tubs of cold water, their eyes focused intently on the strands of fiber at their fingertips, day after day. It is cold, unforgiving work.

Women crouched at work removing stray debris from the fibers, their fingers numb from constant immersion in cold water. Workers need to wrap up well to ensure they do not freeze during the long hours of work in the bitter cold.

Women crouched at work removing stray debris from the fibers, their fingers numb from constant immersion in cold water. Workers need to wrap up well to ensure they do not freeze during the long hours of work in the bitter cold.

In the quiet of the workshop, the only sound is the heavy slapping of the water as it sloshes in the tubs. In the gentle light that streams in through the high windows of the workshop, the papermakers stand like shadow puppets before the tubs of paper and water, their breath pluming before them as they work. They wear high rubber boots, rubber aprons, and have their sleeves rolled up to their elbows.

The large bamboo suki-geta they hold between them moves slowly in a seesaw motion through the milk-white mash until, moving as one and seeming to coordinate their very breath, they lift the freshly made sheet of paper from its watery cradle.

“It’s difficult to tell the thickness of the paper with the lights on,” says one of the workers. The workshop is lit entirely by natural light. Judging thickness by the translucency of the paper, these highly experienced artisans can produce sheets of almost uniform thickness by sight and feel alone. These subtle gradations of color can only be distinguished in natural light, which comes in through the frosted glass of the workshop windows.

Handmade torinoko paper, freshly pressed in the winter cold. The name comes from the paper’s color, which is said to resemble that of an egg.

Handmade torinoko paper, freshly pressed in the winter cold. The name comes from the paper’s color, which is said to resemble that of an egg.

The only heat comes from a small charcoal brazier the workers use to restore feeling to their numb fingers. The cold is essential to making fine-quality washi.

A pair of workers can produce 60 to 70 sheets of large-size ōban paper a day. The job of standing at the tubs pressing paper was traditionally considered women’s work in Echizen, but today men do the work too, thin wisps of steam rising from their hands, numbed red from long immersion in the cold water.

“Our hands dry out if we’re not touching the paper,” says one. These words are testimony to the artisans’ dedication to keeping this ancient craft and its traditions alive, despite the unforgiving nature of the work. The natural raw materials pass through many such pairs of well-practiced hands as they undergo the transformation from humble bark to the “king of papers.”

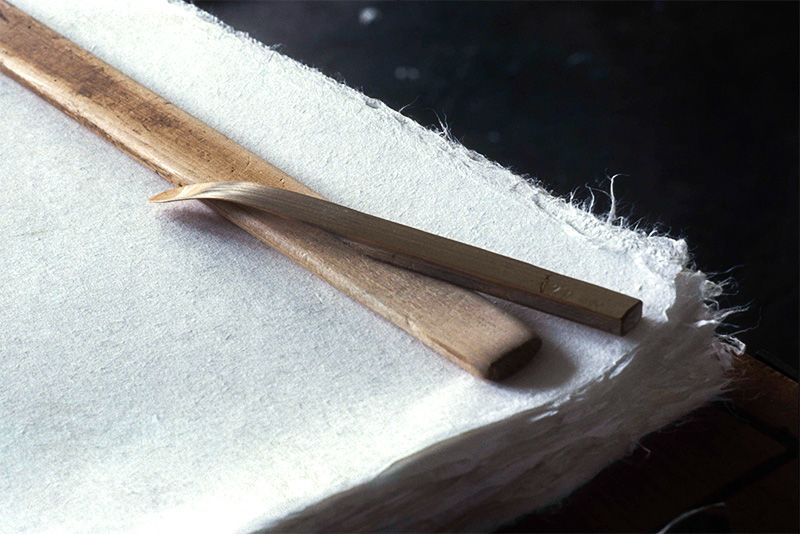

The simple bamboo tools of the washi-making trade: the suki-su lying atop the suki-geta.

The simple bamboo tools of the washi-making trade: the suki-su lying atop the suki-geta.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 7, 2017. Interview and text by Mutsuta Yukie. Photos by Ōhashi Hiroshi. Banner photo: Artisans work without heating despite the winter cold, producing sheets of even thickness by judging the translucency of the paper in the natural light that comes through the windows.)