The “Evacuate Can” Project: Tsunami Readiness in a Kōchi Community

Disaster Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Getting People Ready to Run

In December 2024, a unique disaster preparedness project was announced by the canning company Kuro Can, a “third sector” outfit operating in the nongovernmental space, and home improvement store operator Futagami in the town of Kuroshio, Kōchi Prefecture.

Dubbed the “Evacuate Can” Project, it plans to firstly sell bright blue emergency food cans with a pictogram of a running figure at home improvement stores across Kōchi, and aims for nationwide release on Disaster Prevention Day, September 1.

The cans, bearing graphics urging prompt evacuation and containing rice with bonito that’s delicious even unheated, are currently being developed by Kuro Can. (Courtesy of Kuro Can)

Kuroshio is at risk of experiencing a massive tsunami more than 30 meters high when the anticipated Nankai megathrust earthquake hits. “In Kuroshio, instead of preventing the effects of the giant tsunami, we’re focusing on the mindset of preparedness,” said Kuro Can executive Tomonaga Kimio in an interview. “Our mantra is ‘when it shakes, evacuate.’ Through our canned goods, we want to spread this way of thinking worldwide.”

Kuroshio is a small town in the western part of Kōchi Prefecture, on Shikoku’s Pacific-facing coast, with a population just under 10,000. Known for its pole-and-line fishing fleet, it ranks among the top in skipjack tuna catch volume in Japan.

In March 2012, a new revelation shook the seaside town. The estimated distribution of seismic intensity and tsunami height in the event of a megaquake occurring along the Nankai Trough, running along the Pacific coast of West Japan, were announced. If an earthquake of similar magnitude to the March 11, 2011, Great East Japan Earthquake were to occur, a vast area spanning from the Kantō region to Shikoku and Kyūshū could experience significant tremors and tsunamis. Kuroshio in particular would be at risk of a colossal tsunami reaching a height of 34.4 meters. The town nearly succumbed to a mood of resignation.

The Evacuation Lessons of the “Miracle of Kamaishi”

In the spring of 2013, Ōnishi Katsuya, the mayor of Kuroshio, visited Katada Toshitaka, a specially appointed professor at the University of Tokyo.

In the city of Kamaishi, Iwate Prefecture, many lives were lost to the tsunami in 2011. However, students of elementary and junior high schools in the coastal area facing Ōtsuchi Bay helped each other escape to higher ground, and all 570 pupils survived. The central person behind this “miracle of Kamaishi” was Katada, who had been responsible for disaster preparedness education in the city until a few years before the disaster.

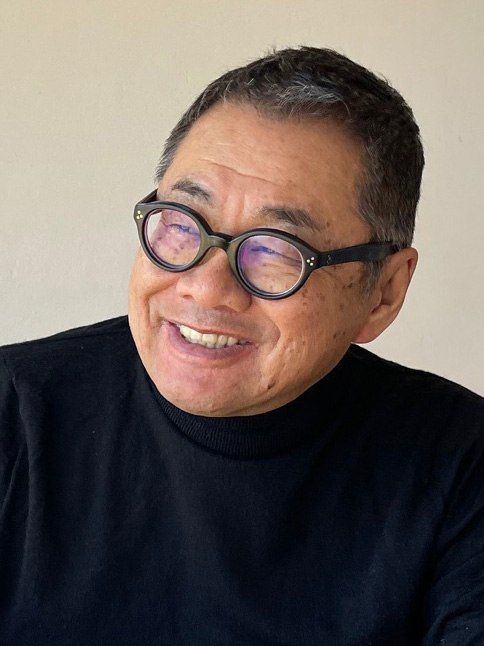

Katada Toshitaka, specially appointed professor at the University of Tokyo. (Courtesy of Katada Toshitaka)

Katada, alarmed that the children were overestimating the protection that the community’s seawalls offered, set out to change their mindset. He instilled three key evacuation principles: “don’t take anything for granted,” “do your utmost when the time comes,” and “be the first to evacuate.” He repeatedly urged them to take responsibility for themselves and flee to higher ground.

When Ōnishi confided to Katada that he wasn’t confident in protecting his townspeople, Katada responded with some humor.

“Mayor Ōnishi, maybe it’s a good thing that you’re ‘most at risk.’ Your town’s relationship with the ocean hasn’t changed, even after the 2011 disaster. Yes, disasters strike from time to time, but the ocean is a blessing to you. It’s provided you a way of life for generations. To govern in fear of a once-in-a-millennium catastrophe is a misguided approach. Listen: Being ‘most at risk’ is an opportunity to change your people’s mindset.”

Soon after, Katada was welcomed as the disaster advisor for Kuroshio, and a disaster preparedness plan was formulated. Its opening section laid out a clear determination:

With the core principle of protecting the lives of residents, we will continue to build a town that thrives on the blessings of the sea. . . . We will confront the Nankai Trough quake threat head-on and continue to develop our town with our tsunami preparedness plan, one of the best in Japan.

Disaster preparedness education became a top priority, with heavy emphasis on the importance of immediately evacuating to a safe location after a quake. Comprehensive training aimed to make sure that every individual would be ready to do everything they can for their own evacuation. For children in particular, “life training” was rolled out to enhance their power to survive when the time came.

Evacuation drills are repeatedly conducted in Kuroshio. (Courtesy of the Kuroshio municipal government)

Based on the plan, more than 500 disaster drills have taken place in all, for the town as a whole and for specified districts in it. In areas where evacuation is challenging, tsunami evacuation towers have been constructed. Practical workshops where community residents collaborate and evacuate via the shortest routes, as well as nighttime evacuation drills, are also a part of the program.

To maintain momentum for earthquake preparedness, the company Kuro Can was established. It has been working on developing emergency food products as a disaster mitigation project, and its sales have been growing.

A scene from a workshop where evacuation plans are shared within the community. Town residents have deepened their communication through the drills. (Courtesy of the Kuroshio municipal government)

Resistance to Fortresslike Seawalls

The Evacuate Can Project can be traced back to the discomfort that local Kōchi designer Umebara Makoto felt.

Along the coastlines in the areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, concrete seawalls are being built alongside roads. While the ocean lies just beyond these walls, it is no longer visible from the road. Looking at photos of the seawalls, Umebara was left dumbfounded. “What is this? This just isn’t right.”

The total reconstruction budget for the Great East Japan Earthquake totaled some ¥32 trillion yen over 10 years. By fiscal 2020, ¥1.3 trillion had been allocated for seawalls, and approximately 432 kilometers of walls were constructed along the coasts of the three most affected prefectures, Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima.

“Is this really the kind of reconstruction the people in the affected areas wanted?” Umebara asks. “Is covering the coastline with concrete really the right way to prepare for tsunamis? This is a problem that we all need to think about together as citizens.”

Landscapes have always been important for Umebara, who was born and raised in the nature-rich environment of Kōchi. He has been relied upon as a source of wisdom by local governments in Kōchi and elsewhere, along with primary industry producers, working on everything from creating concepts for local products to comprehensive plans for municipalities.

One of his most notable works is the Sunabi Museum, a project at Kuroshio’s Irino Beach, which has been ongoing since 1989.

Irino Beach in Kuroshio also offers natural shoreline protection. (Courtesy of the Kuroshio municipal government)

In this “museum,” the 4-kilometer long beach, the ocean, and the sky are presented as a work of art in their natural state. On the official website, there is a line from the project proposal that Umebara submitted to the town a quarter of a century ago:

There is no Art Gallery building in our town.

But our beautiful beach is our Art Gallery.

At the Sunabi Museum’s biggest event, the T-Shirt Art Exhibition, rows of t-shirts flutter in the wind. (Courtesy of the Kuroshio municipal government)

The Sunabi Museum was a form of resistance for Umebara. During Japan’s bubble economy in the 1980s, resorts were being developed even in regional areas. Kuroshio also was presented with a development plan, but when the town consulted Umebara, he proposed the “museum” concept instead.

He also incorporated in the Evacuate Can Project some resistance against the forces that erase the landscapes of affected areas.

In the spring of 2024, a decade after Kuro Can was founded, Umebara learned of the company’s interest in collaborating with Futagami, a local home improvement store operator. He proposed the concept that eventually became the Evacuate Can at a meeting that connected the heads of the two parties.

Kuro Can was established as part of a disaster mitigation project following the projections of a massive tsunami. The logo’s 34M signifies the projected wave height. (Courtesy of the Kuroshio municipal government)

Umebara, tasked with package design, made it so that when you rotate the can in the direction of the running pictogram, you see the words “emergency canned food; a delicious meal.” It’s a lighthearted message that a good meal awaits you after evacuation.

Takahashi Hiroyuki, from Hanamaki, Iwate Prefecture, runs Amekaze Taiyō, a website that connects product creators with consumers. He has high praise for the Evacuate Can Project. “The dedication to prepare for the tsunami while continuing to coexist with nature is wonderful!”

Takahashi ran for governor of Iwate Prefecture in September 2011 after the Great East Japan Earthquake, opposing disaster prevention measures centered on seawalls, but he lost the election.

“There’s a tension between a possible extraordinary occurrence that might take place on a single day once a century and the remaining 99 years and 364 days. How to deal with this is up to the community. Unfortunately, in the Tōhoku area, reconstruction has been premised on the extraordinary, and the lives and mindsets of the residents, once in harmony with nature, have changed.”

The affected areas continue to suffer from a significant population outflow. “What was the reconstruction all about? This is an issue that all citizens must confront,” says Takahashi.

After the 2011 earthquake, Kuro Can’s Tomonaga, then a Kuroshio town employee, was involved in supporting the affected areas in Tōhoku. The sight of Rikuzentakata, Iwate, once a place resembling Kuroshio’s own landscape, reduced to rubble, remains etched in his mind.

“It was tough,” recalls Tomonaga. “It was like being shown the future of my own town.”

Tomonaga also shares his thoughts on the areas hit by the January 1, 2024, Noto Peninsula earthquake.

“During a debate on the reconstruction of Noto, somebody said, ‘Should we be pouring money into regions facing extinction?’ That was hard to hear. However, with the approach of the Evacuate Can Project, which encourages individuals to take responsibility for their own safety, the underlying message is: ‘We will evacuate. Therefore, we don’t need to spend vast sums of money on preventive facilities.’ My wish is that people retain their local landscapes and think about reconstructions that sustain the small, everyday things in life.”

(Originally published in Japanese with editorial assistance by Power News. Banner image: The Evacuate Can raises awareness of the need to flee when disaster strikes [courtesy of Kuro Can]; local students take part in an evacuation drill [courtesy of the Kuroshio municipal government].)