Success Often Elusive for Asian Students in Japan: Many Dreamers Defeated by Kanji, Culture, Costs

Society Education Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Background

The number of foreign students in Japan has been climbing since 2023, after plummeting as a result of COVID-19 border measures. Enrollees at Japanese-language schools account for a growing percentage of these international students.

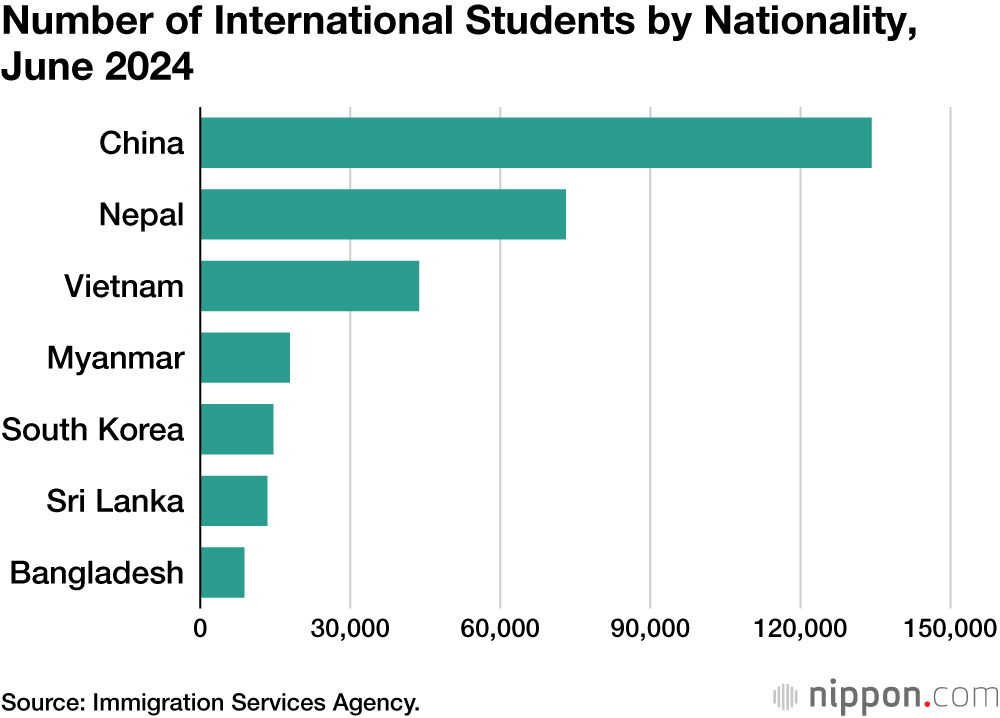

As of June 2024, Japan was host to some 370,000 international students, according to figures from the Immigration Services Agency. The largest number are from China (134,239), followed by Nepal (73,136), Vietnam (43,760), Myanmar (17,917), South Korea (14,610), Sri Lanka (13,409), and Bangladesh (8,828).

Of these students, more than 90,000 were enrolled in Japanese-language schools as of the latest survey by the Japan Student Services Organization (May 2023). Enrolling at a Japanese-language school is a relatively easy way of entering Japan for study purposes, and many Asians do so with high hopes for the future. But not all are prepared for the mental, physical, and financial struggles involved in learning enough Japanese to build a career in this country. I spoke with a sampling of students and teachers at a Tokyo Japanese-language school to get a first-hand account of the challenges they face.

According to the ISA, as of February 2025 there are more than 850 Japanese-language institutes nationwide, and one must be wary of overgeneralizing about them or their students. Nonetheless, my interviews yielded some revealing snapshots and insights.

Chinese Students Still on Top, But . . .

At the school I visited, classes are capped at 20 students. They include young people from China, Malaysia, Nepal, India, and Mongolia. Speaking anonymously, several of the school’s teachers confided that their biggest headache was the classroom demeanor of their Chinese students. Too often they were inattentive and even disrespectful, sometimes sleeping at their desks throughout a lesson.

“They have no clear idea of what they hope to accomplish here in Japan,” said one veteran teacher. “It seems like more and more of our Chinese students just aren’t motivated.”

In the 2010s, by contrast, Chinese students had a reputation for working hard and quickly achieving fluency as Japanese speakers. Even now, many are ambitious young people motivated by a clear sense of purpose. But with China’s economy sputtering and youth unemployment soaring, there is a sense that more and more are coming to Japan just to escape the harsh reality of the domestic job market. Lately, teachers say, Chinese students tend to fall into one of two groups: the honor students and the slackers.

When probed, some lament that they have no friends, that they hate studying, that their parents take no interest in them. Overall, they seem to be suffering from the kind of apathy and malaise afflicting young people throughout the developed world.

That said, Chinese nationals continue to outperform most other international students on the standardized Japanese Language Proficiency Test. This is partly because they have a leg up when it comes to memorizing the hundreds of Sino-Japanese ideographs, or kanji, that feature prominently on the tests. Aware that a score at the N1 or N2 level is a ticket to university admissions or a good job at a Japanese corporation, Chinese students are apt to neglect classroom instruction in favor of exam study, according to the veteran teacher quoted above. Supported by affluent parents, they can often get by without working part-time and may even spend their afternoons studying for university exams at test-prep schools after attending Japanese-language classes in the morning.

Students from other Asian countries face a harsher reality.

Struggles with Language and Life

Japanese is considered a “language isolate,” having no proven genetic relationship to any other tongue. Its unusual syntax and complex verb conjugations, including separate forms for honorific language, are daunting enough without the added burden of a writing system that combines kanji with two sets of phonetic characters. For Asian students with no background in Chinese or Sino-Japanese ideographs, passing the JLPT at the higher levels can be a serious struggle.

One Nepali who failed the exam, speaking in halting Japanese, expressed a sense of despair. “We work so hard on our kanji, but we cannot pass the JLPT.” Study is expensive, and the student worries about having enough money left over to enroll in a university.

For the majority of non-Chinese Asian students, the challenge of learning Japanese in a manageable time frame is compounded by the need to earn money, both to support their daily lives and also, in many cases, to pay off the loans they took out to cover tuition and other expenses. Permitted to work up to 28 hours a week under a student visa, many find jobs in convenience stores and restaurants.

Another option is newspaper delivery. While this job often comes with a partial scholarship from the newspaper, the work is strenuous and the schedule grueling. After getting out of class a little past noon, students report to a local sales outlet by 1:30 pm to prepare the evening edition for delivery. They complete delivery and return to tie things up, finishing by around 6:00 pm. That leaves just six or seven hours before they have to report back to get the morning edition ready for delivery. This schedule helps explain why some students arrive late for school, miss entire mornings, or fall asleep during class.

“I have to divide my sleep time into two blocs of a few hours each,” said one Mongolian student. “At the beginning I powered through, but the exhaustion has been building up.”

Inflation has hit international students hard, particularly in Tokyo, with its high cost of living. Some even admit to going hungry at times. “Bread costs so much,” laments a Malaysian student. “I try to make a meal out of a couple of buns, but they don’t fill me up. And the price of fruit here is unbelievable compared with back home.”

Long, Hard Road to Success

The typical international student comes to Japan with fond dreams of building a career or acquiring advanced skills, whether as a beautician, an engineer, or a businessperson. A Nepali student at the school I visited spoke enthusiastically of becoming a fashion designer; a Mongolian student, an aerospace engineer; an Indian student, a leader in his field at a Japanese corporation. But not everyone realizes how much time, effort, and money are needed to achieve such goals.

In many cases, the demands prove to be too much, leaving students with no other option than to give up and go home. I spoke to a student from rural Malaysia who had hoped to study cosmetology at a Japanese vocational school but was obliged to abandon the plan for economic reasons. “On top of tuition, there’s the cost of teaching materials and training fees. When I added it all up, I realized it was more than I could afford.”

A Thai university graduate who had hoped to find work at a Japanese company was having second thoughts after learning more about the norms of corporate culture, beginning with appropriate interview attire. “I’d like to get a job in Japan if I can find a workplace where I’m comfortable, but if not, I’m going home.”

In some countries, people rely on specialized brokers to handle their visa and study arrangements. Among those brokers are shady operators who hit applicants with unexpected fees, forcing the students’ families to borrow heavily. Victims of such exploitation find they have no choice but to exceed the legal 28-hour limit just to pay back their loans. In addition, young people from Asian countries have been known to procure student visas for the sole purpose of skirting Japan’s restrictions on foreign unskilled labor. Such cases have tarnished the public’s image of Asian students.

Investing for the Long Haul

Equipped with the proper educational credentials, a graduate of a Japanese-language school has a shot at lining up a legitimate job, applying for a change in status of residence, and securing legal full-time employment in Japan.

But Japanese corporations looking for foreigners to fill key bilingual positions usually require proof of N1 or at least N2 proficiency, and it can take years for non-Chinese students to attain that level. The less proficient are generally relegated to back-office work. Yet many of the Asians passed over for good positions are hardworking, talented young people with high potential. Shouldn’t Japanese industry and society be investing in their long-term growth?

Seki Kōtetsu has many years’ experience supervising the training of foreign workers at a major human resource service firm in Japan. “It’s vital that businesses and local communities work together to foster non-Japanese leaders with an understanding of Japanese culture, people who can serve as bridges between Japan and other countries,” he says.

But there is another side to the story, as explained by Sugimoto Kiyoshi, whose company, Joint Asia, specializes in placement and recruitment of foreign human resources.

“In the field of IT, for example, Japan has a serious shortage of talent, and plenty of Japanese firms would be more than willing to hire and train qualified foreigners if they could count on them for the long haul,” says Sugimoto. “But companies have been burned repeatedly by foreign recruits who receive their training and then quit, so they worry that their investment will be wasted.”

To tap into the true potential of international human resources, Japanese employers must be willing to make a long-term investment. For that to happen, international students must also commit themselves for the long haul, with a clear understanding of all that entails.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The Shin-Ōkubo district of Tokyo, where many Japanese-language schools are located, is an ethnically diverse neighborhood with a high concentration of residents from other Asian countries. © Jiji.)

Related Tags

Japanese language education foreign workers international students