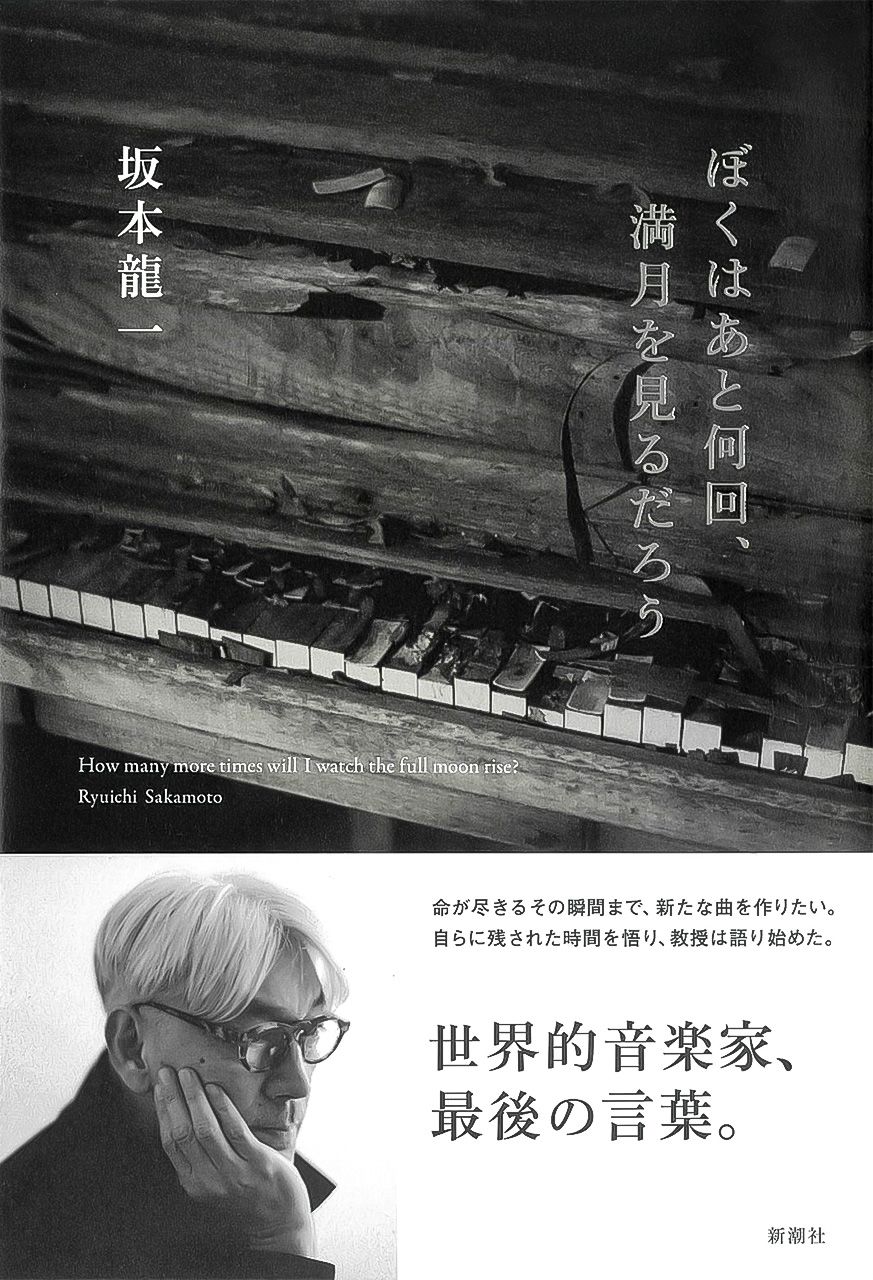

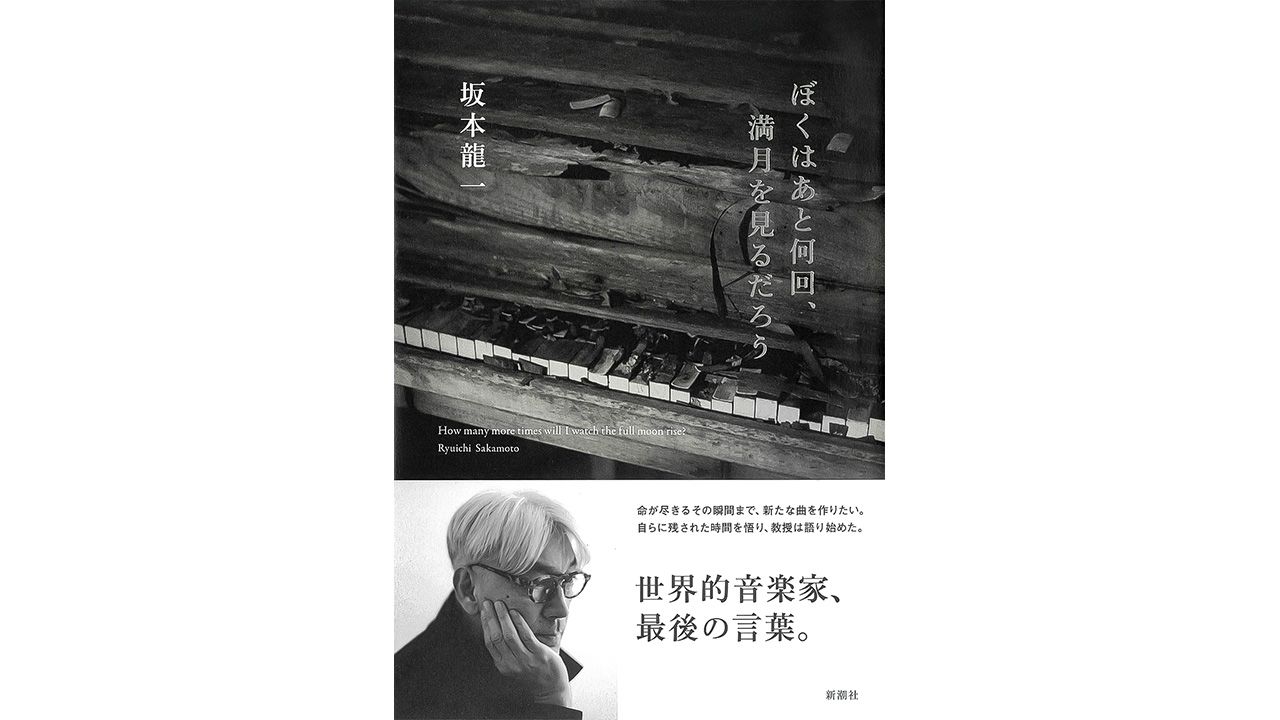

Sakamoto Ryūichi’s Last Testament: How Many More Times Will I Watch the Full Moon Rise?

Books Music- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Six Operations in Two Years

The interviews in Boku wa ato nankai mangetsu o miru darō (How Many More Times Will I Watch the Full Moon Rise?) originally appeared in the literary magazine Shinchō, in a series of eight monthly installments from July 2022 to February 2023. The musician Sakamoto Ryūichi was diagnosed with throat cancer in 2014, but the disease went into remission after a course of radiation therapy. In June 2020, tests at a hospital in New York discovered rectal cancer. Again, he underwent radiation treatment and chemotherapy, but this time the treatment was unsuccessful. Further tests during a visit to Japan in December that year showed that the cancer had spread to his liver and lymph nodes. He was told that without intervention he might expect to live another six months.

When it emerged that the cancer had spread to his lungs, Sakamoto was forced to extend what was originally supposed to be a short visit home and resolved to remain in Japan and fight the disease here. In January 2021 he underwent a 20-hour operation to remove 30 centimeters from his colon. Over the next two years, he underwent six operations in all, including one to remove a tumor from his lungs. Unfortunately, even this failed to eradicate the cancer. The only option remaining was to use drugs to try to control the spread of the disease for as long as possible.

Sakamoto had previously published an autobiography in 2009, looking back on his life and work to date so far in Ongaku wa jiyū ni suru (Musik Macht Frei). This second volume of reminiscences, though, was written in a different state of mind. The book focuses on his life from 2009. “Now, when my illness has forced me to become aware of how little time I have left, this felt like the right moment to look back and reflect on my activities over the past decade or so.” The book is something akin to a final testament, and much of what Sakamoto has to say is marked by a keen awareness of mortality.

Sakamoto concluded his previous autobiography with a description of a new approach to composition: “I try not to add anything. I don’t want to manipulate or assemble things. I am happy just to align sounds as I find them, and study them closely. Then slowly, from out of that, new music starts to emerge.” Following an overwhelming experience of unspoiled nature during a trip to Greenland in the autumn of 2008, his music became increasingly avant-garde and experimental. In this book, Sakamoto explains the background to the many new pieces he wrote from 2009 on. Listening to the compositions of his final years with this account in mind brings the composer’s intentions into clear focus. At the same time, the book also contains detailed and honest accounts of Sakamoto’s social activism, including his charity work and environmental interests, and serves as a reminder of his remarkable energy and devotion to the causes he cared about.

Ars Longa, Vita Brevis

What follows is a selection of passages from the book that stood out in particular:

In the past, Sakamoto used to say that one of his ambitions was to use what time he had left to “write a piece that will surpass ‘Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.’” He explained that the melody for that famous piece came to him in just 30 seconds, leading him to reason that, “Even if my life was extended by just a minute or two, that might be time enough for new music to pop into my head.” But gradually he came to feel that being able to continue to compose in a relaxed frame of mind without any pressure was reward enough. “In some people’s minds, I think the name Sakamoto Ryūichi basically meant ‘Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence’ and nothing more. But I decided I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life working to shatter that cliché. After a certain point, the idea of dedicating my remaining time to that goal struck me as ludicrous. I’ve gone through various changes of heart over the years, I suppose—but that’s the honest, unadorned truth about the state of mind I’ve reached now.”

In July 2011, Sakamoto visited some of the coastal areas that had been devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami disaster just months earlier.

To tell the absolute truth without fear of being misunderstood, the scenes I saw in the disaster areas put me in mind of an extreme art installation—a terrifying artwork that dwarfed anything human ingenuity or creativity could have produced. Of course, this reflected back on my own work. I was overcome by a feeling of impotence. What was the sense of human struggles to create music or other forms of artistic expression in the face of something like this?

In July 2012, he played a prominent role in a major demonstration against nuclear power in Yoyogi Park in central Tokyo, where he made controversial remarks arguing that it was immoral to risk human lives for “mere electricity.”

I don’t have any regrets about anything I said back then, including those remarks about “mere electricity.” People can take those words out of context if they want. I’m going to include a complete transcription here, including the full context. Is it really the case that I argued we didn’t need electricity? Read the remarks in context and decide for yourself.

In January 2020, Sakamoto visited the construction site of the Henoko base during a visit to Okinawa for a charity concert.

The idea that you would destroy this beautiful natural landscape and build a military base there. I mean, all I could think was: What the hell on earth are these people doing?

On the COVID-19 pandemic that started in the spring of 2020, he has this to say:

Now we’re seeing this virus explode all over the world. And it strikes me that one of the ultimate reasons for what is happening is the way in which human societies have hurtled forward with economic overexpansion, in the process destroying ecosystems and turning the whole planet into a concrete jungle. I think it’s important to hold onto our memories of what we are seeing right now, that we don’t ever forget what happened when nature sent out an SOS and slammed on the brakes, bringing the world’s economies grinding to a halt.

On the subject of his activism, Sakamoto writes:

After a certain point, I just didn’t care anymore if people criticized me for my social activism or tried to imply I was somehow trading on my name. I mean, if I do have a certain level of fame, isn’t it right to use that proactively for a good cause? Even if people call me a hypocrite, if the end result is to make our society even a little bit better, isn’t that a good thing? This is the conviction that supports me in everything I do, whether it’s my ecological activities or the work I did in the affected areas after the Tōhoku disaster. Besides, once you’re involved, it’s not easy to quit.”

Another memorable line comes from Sakamoto’s final days, when he has already accepted that death is near. On December 22, he enters an NHK recording studio to record what will be his final solo performance on piano.

I know for sure that I no longer have the physical strength left to make it through a live performance or concert. . . . But I’m relieved that I have successfully recorded a performance I can be satisfied with before I die.”

On January 17, 2023, Sakamoto released a new album, on his seventy-first birthday.

In making this album I really did nothing more than just take sounds played on synthesizers and piano and put them on disc, just as they were. But this kind of pure, raw, unadorned music feels right to me at this moment in time.

After it all, Sakamoto ends with a famous quote: Ars longa, vita brevis. The life of this remarkable musician may have come to an end, but the impact of his work is sure to live on for many years to come.