A Walk around the Yamanote Line

From Okachimachi to Nippori: Bustling Business and Quiet Times Along the Yamanote’s Northeastern Stretch

Travel Lifestyle Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Jewelry Hunters’ Town

Our walk between Okachimachi and Nippori stations is full of surprises, including places like Diamond Avenue and Pearl Street in Okachimachi‘s southern and eastern districts.

Okachimachi offers plenty of good deals for jewelry hunters. (© Gianni Simone)

Forget New York’s Fifth Avenue and London’s Bond Street. This is a plain, nondescript area of Tokyo where you won’t find any high-end stores. Yet, this is Japan’s number one jewelry district, and its streets are lined with dozens of stores where jewelry is sold, processed, and appraised.

Okachimachi offers plenty of good deals for jewelry hunters. (© Gianni Simone)

Strangely enough, the area’s tacky, bling vibe is offset by the intricately exotic smells emanating from its many Indian and Nepalese restaurants whose heady blend of cardamom, turmeric, and garam masala creates a complex and layered aroma that is both comforting and exhilarating.

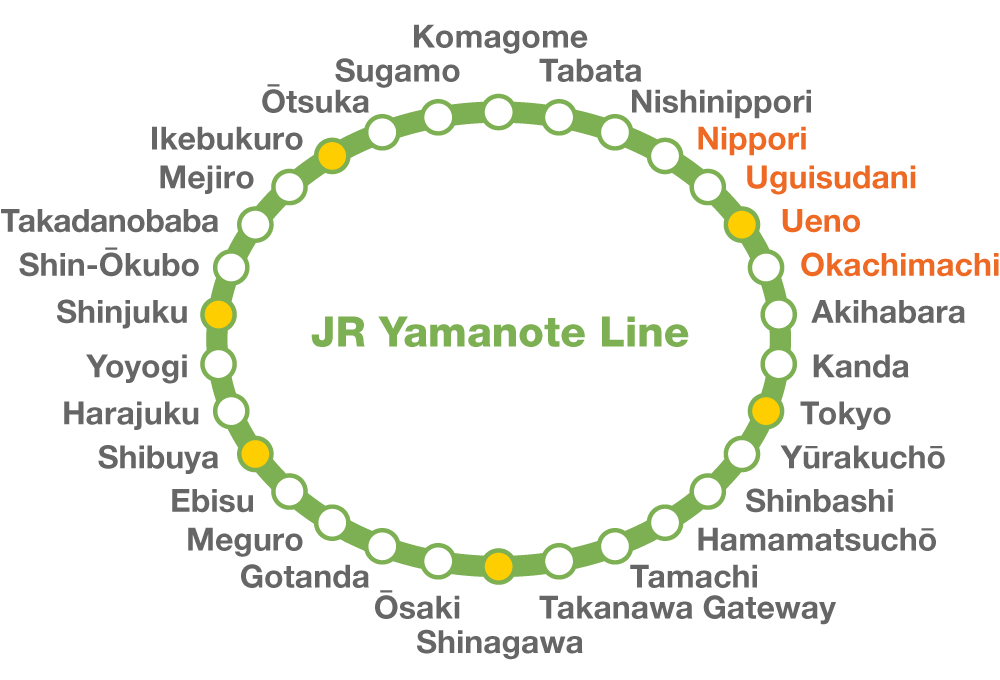

The Yamanote Line’s 30 stations. (© Pixta)

Ueno: History, Museums, Food and More

Okachimachi is connected to Ueno by Ameya Yokochō (Ameyoko for short), a shopping street whose origins date back to the black market of the early postwar years. While in the 1940s and 1950s it specialized in candies (ame in Japanese) and American goods (another source for its Ame– name), the under-the-tracks stalls now sell a variety of products, including sports goods, imported clothing, cosmetics, dried food and spices, and fresh produce.

Ameyoko shopping street in Ueno. (© Pixta)

All day long, the area’s busy alleys are clogged with tourists, but few of them venture inside the Ameyoko Center Building, a little-known spot that represents the ethnic side of Ueno. Fittingly located in its basement, its Underground Food Street is a miniature Asian market selling fresh fish, herbs, spices, seasonings, vegetables, and other products from Thailand, India, Vietnam, and China.

The Underground Food Street inside the Ameyoko Center Building sells food from around Asia. (© Gianni Simone)

Ueno is rich in history. In 1868, at the end of Edo period, it was the last place of resistance for some 2,000 followers of the Tokugawa regime who fought to the death against overwhelming waves of imperial troops. From 1883 onward, Ueno Station connected the capital to northern Japan, and for a long time remained the country’s busiest station.

From the mid-1950s through the mid-1970s, countless thousands of young people from the northern Tōhoku region reached Tokyo on so-called shūdan shūshoku ressha (mass employment trains). Many job seekers, teenagers just out of junior high school, were labeled kin no tamago (golden eggs). They found employment in the city’s factories, shops, and construction sites, contributing to Japan’s “economic miracle.”

In the past, Ueno Station had a dedicated platform—number 18—for those trains. That platform does not exist anymore, but at the entrance to platform 15, there is a monument to those unsung heroes. It is inscribed with a tanka poem by Ishikawa Takuboku that reads, “I miss the accent of my hometown, I go to listen to it in the crowd at the station.” Another monument in front of the station is devoted to “Ah, Ueno Station,” a song by Izawa Hachirō that was popular among migrants at the time.

At left, Takuboku’s verse is immortalized at Ueno Station; at right is the monument to Izawa’s celebrated song. (© Pixta)

If Ameyoko retains the scent of the postwar black market, Ueno Park, lined with numerous museums, has a vibe of science, art, and learning. There are many ways to reach the park. One of them is the East-West Free Passage, also known as the Panda Bridge. It was built in 2000 to make it easier for people on the east side of the station, which has fewer open spaces, to evacuate to Ueno Park on the west side in the event of a disaster.

Besides the usual crowds of families, couples, and tourists, Ueno Park is one of the rare places in central Tokyo where you will find not a few homeless people. I see one lying down in front of the station, where a passing police patrol lets him be. Another one has found a comfortable spot behind an information board. Headphones in his ears, he is reading a paperback.

Many homeless can usually be found at the back of the park. They are mostly older guys, many wearing masks and baseball caps, some of them discarded by society after being used during the years of rapid economic development.

Another place that most tourists miss is Kan’eiji, right behind Ueno Park. It’s such an irony that this Buddhist temple, which during the Tokugawa regime (1603–1867) held so much power, lies today half-forgotten, just a 10-minute walk from one of Tokyo’s most popular and crowded spots. Off-limits to most people in the time of the shōgun, now nobody cares about it.

Completely destroyed during the battle that ended the shogunal regime, Kan’eiji currently occupies a fraction of its original sacred grounds. Yet, it’s still well worth a visit. At the very end of its cemetery, one enjoys a strange panoramic view of tombs, passing trains—including our beloved Yamanote—and seedy hotels. Those are the buttresses of our next destination.

The rebuilt temple Kan’eiji presents a quiet face among its noisy surroundings. (© Pixta)

Sound of Silence: Bush Warbler Valley

Uguisudani embodies psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s theory according to which people are ruled by two primary forces: the sexual or life instinct (Eros) and the death instinct (Thanatos). Eros can be found at the station’s north exit, whose immediate surroundings are dominated by one of Tokyo’s major clusters of love hotels. Once a popular geisha quarter, this area has become a veritable citadel of sex. A gray, malodorous place of greasy cafes, dirty public toilets (forget Wim Wenders’s Perfect Days), and kebab shops, this district is a downgraded, bargain-sale, B-movie version of Tokyo. And to think that Uguisudani (Bush Warbler Valley) used to be connected to nature and beautiful birdsong.

Uguisudani’s north exit has a large love hotel district. (© Gianni Simone)

If the north exit is lively and rather overcrowded, very few people live on the other side of the station since it is entirely occupied by Kan’eij’s vast cemetery. For this reason, Uguisudani has by far the Yamanote Line’s second-lowest number of daily users, leading only the newly established Takanawa Gateway station (about 23,000 according to a 2023 JR East survey).

Indeed, the inner area from Uguisidani to Nippori and beyond is crowded with temples and cemeteries. During the Edo period, Nippori was on the outskirts of Tokyo. Many wooden temples were moved here from the city center to lessen the risk of fires, and their grounds were preserved as fire breaks.

Ironically, the temples’ original locations around Edo Castle burned to the ground several times, while the districts around Nippori Station not only have never experienced significant fires but were also spared by both the 1923 Great Tokyo Earthquake and the American bombings at the end of the Pacific War.

Yanaka is one such place. Located inside the Yamanote loop, this historical neighborhood has retained much of its old-world charm and architecture. Dating back to the Edo period, Yanaka flourished as a temple town and over the years has become a sanctuary for many craftsmen, shopkeepers, and artists.

Jōmyōin, just to the west from Uguisudani, is one of the best-kept secrets among Tokyo temples. (© Gianni Simone)

Coming from Uguisudani, we enter the Yanaka Cemetery (one of Tokyo’s three main burial grounds almost by mistake, what with the lack of walls or gates. People use it as a shortcut through the neighborhood, and it’s not uncommon to see joggers and commuters on their bicycles. Strolling around its quiet lanes, I find the occasional beer can and even a playground at the edge of the area. Again, the living and the dead share space and a modicum of quiet.

In Uguisudani, Eros and Thanatos are only separated by the railway tracks. (© Gianni Simone)

This cemetery is a sort of liminal space suspended between completely different worlds. It is such a vast maze (25 acres containing 7,000 graves) that you easily get lost, and the only way to keep your bearings is to follow the rumbling noise of the trains passing near the foot of the hill, out of sight.

Yanaka offers much more than tombs. Nature’s greens and browns abound. It smells of dirt and flowers and new leaves, with the only sounds to hear being the temple bells and the wind rattling the memorial name staves near the tombs. This must be one of central Tokyo’s most peaceful neighborhoods. The Yanaka Ginza shopping street and Asakura Museum are the spots on every tourist’s list these days, but I believe the winding alleys around them are even more interesting.

If you are not tired of temples, visit Tennōji, founded more than 700 years ago, where you are welcomed by a seated bronze Buddha, and Kyōōji, whose wooden gates still sport bullet holes dating back to 1868, another reminder of the bloody end of the Tokugawa regime.

The bullet holes at Kyōōji are a reminder of the dramatic end of Japan’s premodern age. (© Gianni Simone)

A Town for Fashion Creators: Nippori

We end this walk by crossing the tracks at Nippori Station. On the outer side of the loop, we are reminded that unfortunately, Tokyo has precious little green. Data shows that the central 23 cities of metropolitan Tokyo are 82% covered with asphalt and concrete (in comparison, London is 62% urban and 30% parkland).

Nippori’s east side is all hard surfaces, gray buildings and the asphalt in which they are embedded. The overall feel is an impersonal environment, only broken by the bright colors of Nippori Sen’igai (Textile Town), where you will find tons of fabrics, buttons, ribbons and tools to make your dream dress.

Nippori Textile Town, a dressmaker’s paradise, attracts handicraft-minded tourists from around Japan and all over the world. (© Gianni Simone)

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: Jōmyōin is one of the best-kept secrets among Tokyo temples. © Gianni Simone.)

Related Tags

Ueno walking Yamanote Line Okachimachi Nippori Uguisudani Ameyoko