The Gods of Japanese Myths and Legends

Serpent Tales: Snakes in Japanese Mythology and Folklore

Guide to Japan Culture History Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In Japan and throughout the world, snakes are prominent characters in mythology, from menacing creatures to guardian deities to awe-inspiring symbols of transformation and rebirth. The earliest suggestion of the spiritual role of serpents in Japan is found in their depiction on earthen vessels from the prehistoric Jōmon period.

Hirafuji Kikuko, a professor of Shintō studies at Kokugakuin University and specialist in mythology, points to the peculiar traits of snakes as making them powerful symbols. “Their manner of sloughing off their skin in one piece,” she explains, “led many cultures to consider them emblems of death and rebirth.” She says that in Jōmon Japan “snakes would have been familiar aspects of people’s lives, but would have retained a sense of mystery about them.” This spiritual aura gave rise to Japan’s many serpent-based legends.

Serpentine Terror: Yamata no Orochi

The myths told in works like the eighth-century Kojiki and Nihon shoki and numerous regional accounts known as fudoki are filled with animal figures that had symbolic meanings for ancient Japanese. Hirafuji explains that snakes joined the pantheon of spiritual creatures in part through their connection with wet rice cultivation, which became established in the Yayoi period (300 BCE–300 CE). “They would have been common sights around paddies and irrigation canals, leading to their association with water—an essential component of rice farming—both as messengers of deities and as guardians of waterways and farmlands in their own right.” Their sinuous bodies also saw them depicted in some legends as numen of thunder and lightning.

At the same time, snakes represented the darker forces of nature that must be overcome, as demonstrated in countless tales from around the world of brave heroes slaying serpent-like monsters. Japanese mythology has its own rendition on this theme featuring the fearsome eight-headed, eight-tailed titan, Yamata no Orochi.

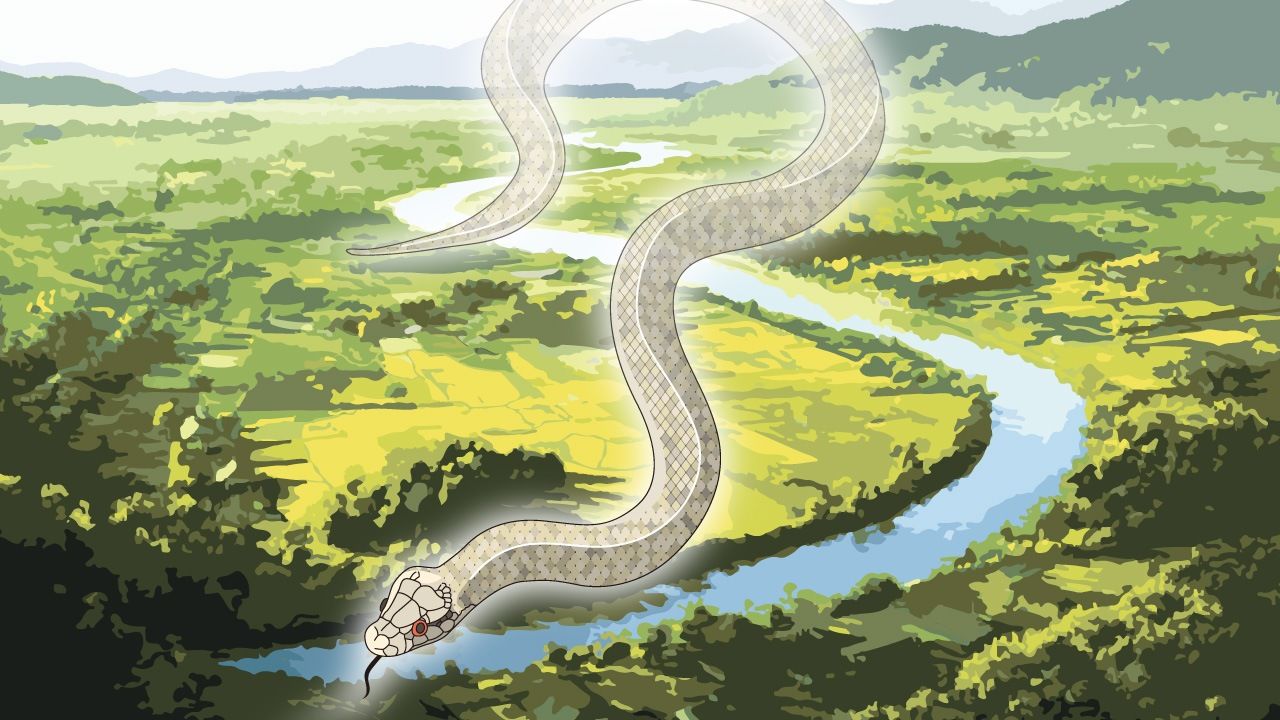

The story is set in the ancient Izumo Province in the eastern part of what today is Shimane Prefecture. Hirafuji describes the horrible appearance of the Yamata no Orochi: “It’s depicted as being the length of eight valleys and eight mountains, and has a body covered in moss and cypress and cedar trees.” The rampaging monster terrorizes the land, devouring seven daughters of a family, one at a time. But before the Yamata no Orochi can claim the last child, the princess Kushinadahime, the deity Susanoo appears and vanquishes the serpent, lopping off its eight heads and restoring peace to the land.

Hirafuji suggests agricultural roots for the myth, with Yamata no Orochi symbolizing the unpredictable Hii River. “On the one hand, farmers were reliant on the river for water, but it was also the cause of destructive floods.” In this interpretation, the serpent symbolizes the turbulent river bursting its banks in a bout of seasonal pique, with Kushinadahime representing the crops and farmland placed at the mercy of the rampaging waters.

However, Hirafuji points to another theory that links the Yamata no Orochi myth to the introduction of iron technology in Japan. “In the story, the serpent is described as having glowing red eyes and a swollen underside that is stained crimson with blood, images that bring to mind the flames of an iron forge.” From its tail, too, emerges an iron sword believed to be the Kusanagi no Tsurugi, a blade that is one of the three sacred treasures of the Japanese imperial household.

Giving further weight to this interpretation is Izumo’s long history as a center of tatara iron- and steelmaking, a technique that utilizes charcoal-fired furnaces equipped with bellows to melt iron sand. The resulting high-grade metals were a specialty of the region. The Izumo no kuni fudoki compiled in 733, for instance, sings the praises of Izumo iron, describing it as “sturdy and good for making all manner of tools.”

Hirafuji suggests the myth’s themes illustrate a shared heritage of Eastern and Western civilizations around iron-making technology. “The Hittites had a similar legend featuring a serpentine beast,” she explains, referring to the ancient inhabitants of modern-day Turkey who developed new techniques for using iron around the fifteenth century BCE. “It tells how the monster Illuyanka, lured from its hole in the ground by a huge banquet, grows fat on food and wine. Unable to return to its lair, the creature is subdued by the hero Hupasiyas.” She points to such aspects as Susanoo’s use of sake to mollify Yamata no Orochi before slaying it as paralleling the Hittite myth, hinting at a gradual spread of ideas.

Snake on the Mountain

Another common theme in mythology is human-animal marriage involving supernatural beings, who upon discovery revert to their true forms. Snakes are represented in this genre in Japan in many ways, such as one curious tale of a woman who falls in love with a mysterious man and gives birth to a serpentine child. The most representative myth, though, is from Mount Miwa in Nara and involves the deity Ōmononushi, who appears in the form of a white snake.

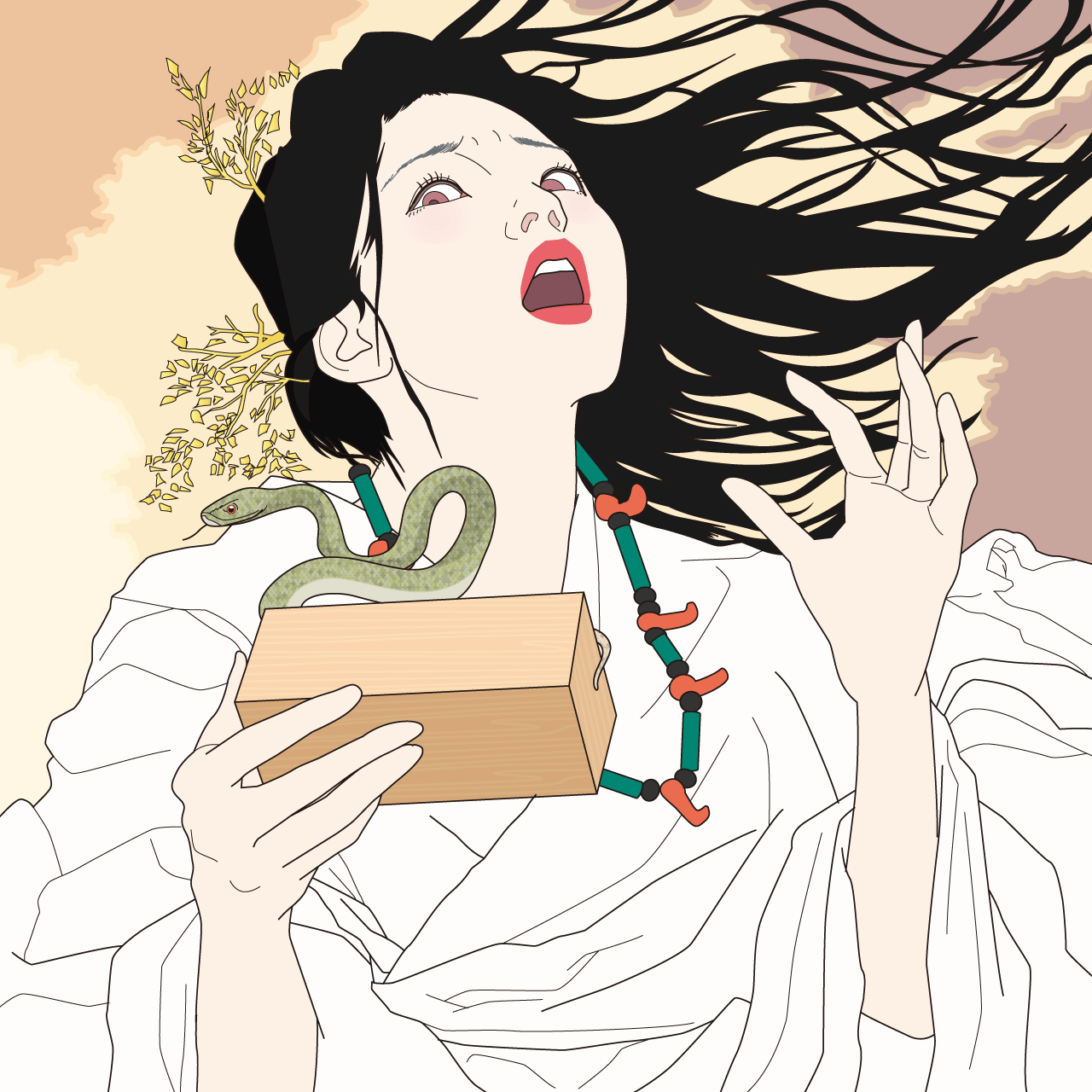

The story, contained in the Nihon shoki, relates how the princess Yamato Totobi Momoso, the daughter of seventh emperor Kōrei, marries, but that her husband only visits her at night. Wanting to see his face in the daylight, she asks her spouse to show himself in the morning, to which he agrees, telling the princess to open her comb box, but admonishing her not to be surprised by what she finds. In the morning Yamato Totobi Momoso opens the box and lets out a shriek at the discovery of a small snake hiding within. Indignant at his bride, the snake husband disappears into the mountains.

Yamato Totobi Momoso cries out in surprise at finding a snake in her comb box. (© Satō Tadashi)

The Kojiki contains a similar myth about a beautiful maiden who lives in matrimony with a handsome nighttime visitor. Wanting to know his identity, she passes hemp thread through the skirt of his garment with a needle. Following the trail in the morning, she finds the line of thread has gone through the keyhole and extends all the way to Ōmiwa Shrine on Mount Miwa, where a snake a deity is known to reside.

Ōmiwa Shrine is dedicated to deities associated with such pursuits as agriculture, business, and medicine. The grounds are purported to be inhabited by a white snake—the manifestation of Ōmononushi. The revered shirohebi makes its abode at the base of an old cedar, the Minokami sugi, and is believed—snakes being symbols of renewal—to have the power to cure disease. In an age-old custom, followers leave a raw egg—a favorite food—as an offering against infectious maladies. The deity is also sacred to sake brewers, with bottles of sake proffered side by side with eggs, creating a peculiar sight.

Offerings of eggs and bottles of sake at the Minokami sugi. (© Pixta)

Serpents and Dragons

In shape and behavior, it is just a small step from real-world snakes to mythical dragons. The imaginary beasts came to Japan from China, where they are depicted as lithe, scaled creatures with shining eyes, deer horns, flowing whiskers, and clawed feet. The Chinese dragon is a symbol of luck and blessing as well as political power through its association with China’s emperors. In Japan, dragons, called ryū, are believed to have arrived sometime around the third century BCE, which is when they first begin appearing as motifs on Yayoi pottery and bronze mirrors.

Hirafuji explains that the image of dragons spread in Japan at the same time that Buddhism, which venerates the mythical animal as a guardian, was taking root in the country. This influence can be found in later depictions of the Yamata no Orochi. “Early records describe Yamata no Orochi as being a giant snake,” she says. “By the Middle Ages, though, it had taken on the form of a dragon.”

Over time, the worship of snakes and dragons as sacred creatures became nearly indistinguishably entwined. November, for instance, is purported to be when the myriad gods of Japan gather in Izumo for an annual conference in which they discuss their respective realms. The arriving deities first alight at Inasa Beach west of the grand shrine, from where they are ceremoniously led to Izumo Taisha by Ryūja-jin, a dragon-serpent spirit and divine messenger of Japan’s mythical founder Ōkuninushi.

Inasa Beach and the Sea of Japan beyond. (© Pixta)

Ryūja-jin is revered in his own right as a guardian deity of farming, fishing, and family fortunes. The model for the god is the yellow-bellied sea snake found in Japan’s southern waters, where it is known as seguro umihebi. Although not native to Izumo, the brightly colored, venomous snakes are known to drift northward on the warm currents that begin to flow through the Sea of Japan around November, and sometimes make their appearance in the waters off Izumo’s coast. Ancient inhabitants of the region referred to these visitors as ryūja-sama, a term combining the kanji for both dragon and snake. When found, they were presented as offerings at Izumo Taisha and other important shrines in the area, or proffered at household altars.

The snake’s rise to divine messenger is attributed to the belief among early Japanese that kami inhabited a heavenly realm and only visited the earthly domain when called on to do so. The sea served as the boundary dividing the celestial (tokoyo) and temporal (utsushiyo) lands, and the seguro umihebi attained spiritual status for its habit of seeming to appear from and then return to the sacred world of gods.

Stepping into a Mythological Landscape

Two views of the Hii River. The important waterway is the setting of the Yamata no Orochi myth. (Photographed in 2024; © Hirafuji Kikuko)

Hirafuji has frequently travelled to Izumo in a desire to visit sites connected to Japanese mythology, something she has come to consider her life’s work. Among the abundant locations appearing in folklore, she says the Hii River has special attraction. “When flying in or out of the area, I’m always moved by its widely meandering form, which brings to mind a giant snake heaving across the landscape.”

The river flows across eastern Shimane, passing through Izumo before discharging into Lake Shinji. Following the Hii in the opposite directions, toward its source in Okuizumo, leads to Lake Sakuraorochi, which was formed by the building of Obara Dam. “Several years back I visited the lake and was startled to discover a patch of clouds painted the colors of the rainbow,” Hirafuji excitedly recounts. “It reminded me of a passage in the Nihon shoki describing a group of clouds gathered over the Yamata no Orochi. Many regions in the world associate rainbows with snakes, and I had a sense of witnessing with my own eyes the appearance of the great serpent.”

Clouds over Lake Sakuraorochi glow with the colors of the rainbow in a phenomenon known as saiun. (Photographed in 2021; © Hirafuji Kikako)

Snakes appear in Japanese folklore in myriad forms: as gods, symbols of raging rivers, and the attendants of Japan’s multitude of kami. These representations illuminate the deep relationship Japanese living long ago had with nature, and learning how these are represented in the myths of Japan adds a deeper perspective that will heighten the experience of travelling in this ancient land.

(Originally written by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com and published in Japanese. Banner photo: The Yamata no Orochi and Hii River. © Satō Tadashi.)