Purification Festivals: The Power of Fire and Water

Guideto Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Sacrifices for Achieving Purity

In Japan it has been believed since ancient times that as humans living in the present world, we unknowingly commit transgressions and amass impurities. The chinowa kuguri—passing through a large ring made of thatch—takes place at shrines throughout the country at the two turning points of the year, mainly marked on June 30 and December 31 by the modern calendar. This is a ritual for cleansing impurities that signifies rebirth.

Fervent worshippers of deities and buddhas embark on more stringent purification rituals. These often involve cold-water ablutions; men clad only in loincloths plunge into the ocean, stand under waterfalls, or douse themselves with well water (all of which are especially harsh practices in their midwinter versions). These practices originate in ancient chronicles relating how the founding deity Izanagi, returning from the land of the dead, purified himself at the water’s edge. Other purification rituals involve fire.

A purification ritual under the Shasui Waterfall in Kanagawa Prefecture. (© Haga Library)

Individuals embarking on purification rituals often undergo preparation, such as by renouncing the flesh of cattle, pigs, sheep, and other four-legged animals, or even forgoing chicken, eggs, and seafood for a certain period beforehand.

Here we introduce three solemn festivals centering on purification rituals.

Kanchū Misogi Matsuri

(January 13–15, Kikonai, Hokkaidō)

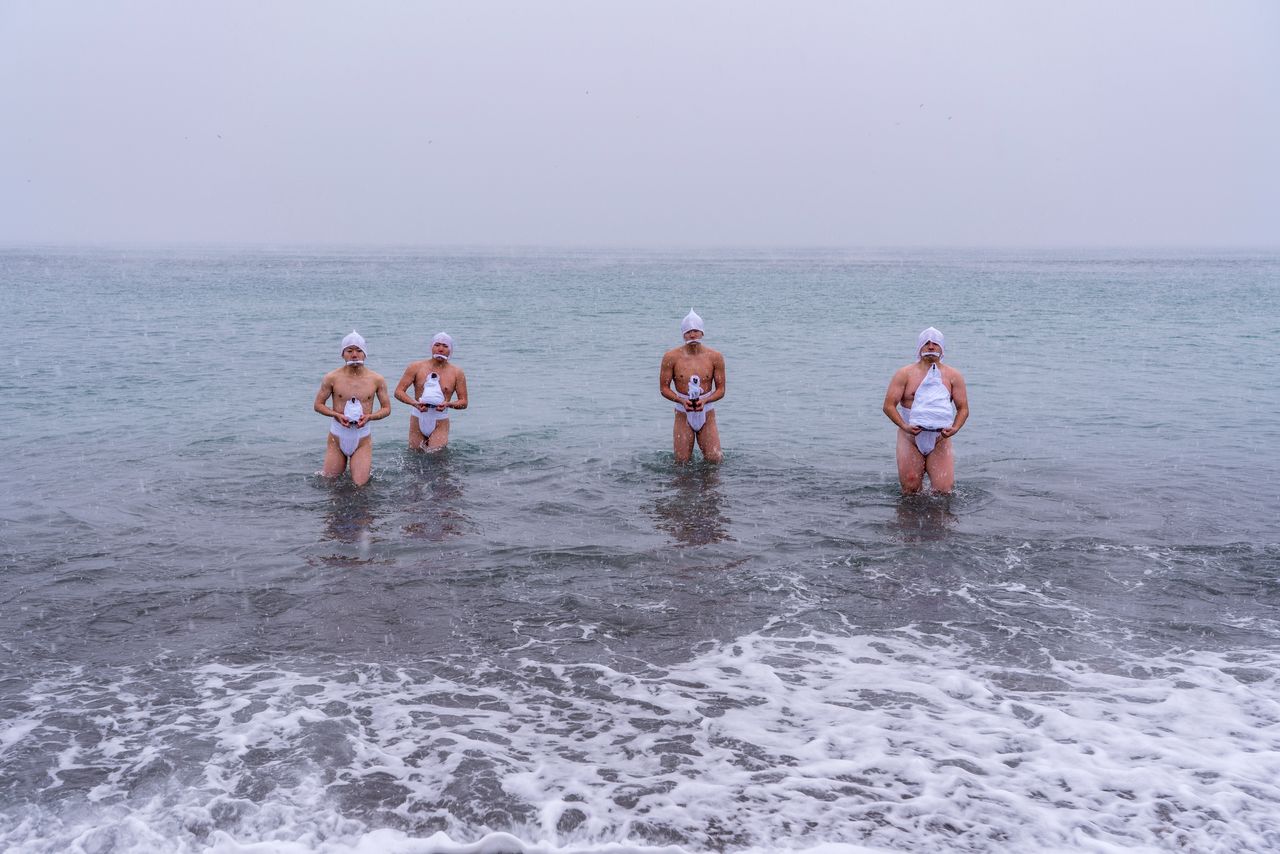

Plunging into the icy sea south of Hokkaidō. (© Haga Library)

The 200-year-old rite at Samegawa Shrine takes place in Kikonai, Hokkaidō. In this festival, men clad only in loincloths plunge into the frigid waters of the Tsugaru Strait.

This festival originated when In 1831, the shrine priest had a dream wherein a divine messenger ordered him to purify the shrine’s goshintai objects of worship. When the goshintai were bathed in the sea, the village prospered. There were plentiful harvests and fish catches, and the village was thereafter spared the worst of the ravages of the Great Tenpō famine of 1833–38.

A white cloth gripped between their teeth, the men brave the cold. (© Haga Library)

Today, the head of the shrine parishioners selects four young men to cleanse the goshintai at Misogihama, around a kilometer southeast of the shrine. In the days preceding the ceremony, the men abstain from meat and conduct ablutions day and night at one-hour intervals. One former participant relates that “the ritual gives you a chance to get in touch with yourself; you can feel your body and soul becoming purified.”

In the bitter cold of winter, performing ablutions requires stoicism. (© Haga Library)

In late afternoon on January 14, the pace picks up as community members join in. They carry lanterns as they proceed to the shrine by the light of bonfires, moving along in the magical atmosphere created by the flames.

Festival drums sound at the shrine as the four men descend the stone stairs and perform ablutions in front of the crowd. Each is doused with water in turn; as they kneel with arms crossed, they move not a muscle, presenting the very picture of strength and fortitude.

Only once they have endured the ablutions are the men allowed to carry the goshintai. (© Haga Library)

The festival climaxes on the third day, when the sea immersion takes place. At 10:00 in the morning, with the temperature well below freezing, the four white-clad men head for the sea carrying the goshintai. As they sink into the frigid water up to their necks for further purification, the men’s expressions convey a feeling of accomplishment.

The goshintai are bathed in the sea. (© Haga Library)

Ōhara Hadaka Matsuri

(September 23–24, Isumi, Chiba Prefecture)

The Chiba shrine’s mikoshi are taken into the sea for purification. (© Haga Library)

Kaisuka Kashima Shrine, midway down Chiba Prefecture’s Pacific coast at Ōhara in Isumi, is considered the guardian facility protecting 18 shrines in the area. Founded during the Jōgan era (859–77), it has held the Ōhara Hadaka Matsuri (Naked Festival) for more than four centuries to pray for plentiful fish catches and abundant harvests.

Men stripped down to the waist carry mikoshi portable shrines through the community for two days. The highlight of the first day is the mikoshi purification in seawater. These mikoshi, whose top structures rest on horizontal poles with no crosspieces, are particular to the region. This is to facilitate weaving and twisting through narrow alleys and change direction, but the inherent instability of the structures makes them difficult to maneuver.

The festival is also well-known for its fisherfolk songs celebrating good catches. (© Haga Library)

On the first morning of the festival, mikoshi from the neighboring shrines assemble at Kashima Shrine. Singers lead the procession, keeping time by clapping their hands as they sing the main festival song, a fascinatingly complex one with hundreds of verses to remember.

Transferring the shrine deity to the mikoshi. (© Haga Library)

Once the shrine priest has transferred the deity to the mikoshi, bearers race them around the shrine precinct three times and finally lift them high in the air. Then they head for the Ōhara fishing port around two kilometers away, twirling and lifting the shrines as they go along.

At the fishing port, bearers fling a mikoshi up in the air, praying for bountiful catches and rich harvests. (© Haga Library)

The procession then moves on to the beach for the immersion rite. Hundreds of near-naked men valiantly bearing mikoshi line up as far as the eye can see, making for a truly stirring sight. At a signal, they all plunge into the sea, the shrines bobbing, weaving, and tangling with each other as spectators’ excitement rises to a fever pitch.

The sea churns with hundreds of men carrying mikoshi. (© Haga Library)

Following purification in the sea, the shrines return to their respective districts. They are washed down, decorated with lanterns, and taken at dusk to a local school, where a grand farewell ceremony takes place. The shrines circle the schoolyard at a dizzying pace once more; the bearers raise them high in the air and gather to sing a song of farewell.

Huge crowds race the mikoshi along. (© Haga Library)

On the festival’s second day, events take place in each district. Then the mikoshi are paraded through the town once more and assemble at the school, where participants sing a plaintive farewell song, pledging to meet again the following year.

A stunning display of lanterns fills the night sky. (© Haga Library)

Takisanji Oni Matsuri

(Saturday nearest to January 7 according to the lunar calendar; in 2025, February 15, Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture)

At this festival, the devils exorcised at setsubun, the day before the beginning of spring according to the lunar calendar, drive out evil. (© Haga Library)

Festivals featuring fire as a means of driving out evil spirits are common everywhere in Japan. Among them is the Takisanji Temple Oni Matsuri (Devil Festival) in Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture.

The temple is closely associated with Minamoto no Yoritomo, who founded the Kamakura shogunate in 1185. One of the temple’s treasures is a statue of the Bodhisattva Kannon (Avalokitesvara) carved by the famed sculptors Unkei (1150–1223) and Tankei (1173–1256), which contains a lock of Yoritomo’s hair. The Oni Matsuri is also said to have been started as a prayer by Yoritomo.

The “grandfather” and “grandmother” devils. The masks were supposedly carved by Unkei himself. (© Haga Library)

Beginning with New Year’s Day according to the lunar calendar, the week-long shūshō-e ceremony to pray for good harvests and peace in the land takes place. On the seventh night, devils who are the messengers of Buddha appear carrying round kagami mochi rice cakes as proof of kechigan—that prayers have been heard.

The three individuals chosen to wear the masks isolate themselves and live at the temple for seven days. During that time, they abstain from meat and perform ablutions to purify themselves. Three masks are in use today—grandfather, grandmother, and grandchild—but there were originally also father and mother masks. Legend has it that the people chosen to play the role of the father and mother devils failed to purify themselves and died in agony after being unable to remove their masks, a story that serves as a lesson to all concerned.

Vanquishing evil with a naginata polearm. (© Haga Library)

On the evening of the last day, the naginata dance, named for the polearm wielded by the main figure, is performed to purify the area in front of the temple’s main hall. Thirty torches are then lit, transforming the temple’s gallery into a sea of flame.

The giant torches are over two meters long. (© Haga Library)

The three devils appear among the flames and exorcise evil spirits from the main hall. The “grandchild” devil, played by a schoolchild, climbs onto the railing amid the flames and performs its role with panache. The grand spectacle put on by the devils has an otherworldly quality—truly a thrilling sight.

The “grandchild” devil carrying the kagami mochi that promises happiness for the coming year. (© Haga Library)

(Originally published in Japanese on February 15, 2025. Dates given are those on which the festivals are usually held. Banner photo © Haga Library.)