Kanten: A Japanese Health Food Boasting a 200-Year-Old Industry

Culture Food and Drink History Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Accidental Discovery in Kyoto

Kanten, or agar, is a dried food made by boiling tengusa or similar type of seaweed, with the liquid then strained and allowed to set, before being repeatedly frozen and dried. After it is boiled one more time to dissolve it and then left to set again, it is used in dishes like mitsumame, a summer dessert where the kanten is cut to look like ice cubes. Due to it being rich in dietary fiber and having almost zero calories, it is gaining attention as a healthy food.

Tokoroten noodles (left), an earlier dish from which kanten derives; kanten as cubes in a mitsumame dessert (right). (© Pixta)

The forerunner of kanten is tokoroten noodles, created by boiling tengusa or similar seaweed, setting the strained liquid into blocks and then using a special press cutter to form it into noodles. This process for tokoroten was introduced from China more than 1,200 years ago.

Kanten has an interesting origin story. One winter in the late 1650s, the owner of the Japanese inn Minoya in Kyoto threw out some tokoroten that a feudal lord had left. During the night it froze, losing its moisture and drying out. When the innkeeper boiled and dissolved it, he found that, compared to the original seaweed jelly, this had less of a briny smell and was more transparent.

Why Landlocked Nagano is the Heart of the Kanten Industry

Although the starting point for kanten was Kyoto, the main producer of this seaweed-based food is the landlocked prefecture of Nagano. In 2023, its shipment value was the highest in Japan, accounting for more than 60% of the domestic market. In particular, the production of kanten in stick form has become a well-established industry in the Suwa region, centered around the cities of Suwa and Chino.

A kanten drying station at the Nagano company Irisen, with the Tateshina mountain range in the background. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

It was around 1840 that kanten production became established in Suwa, beginning with local peddlers who brought kanten-making techniques back from the Tanba region near Kyoto. The climate in Suwa, with its low winter temperatures and a lot of dry, sunny days, along with an abundance of water from the Tateshina mountain range, made it an ideal area for producing kanten.

The advent of the Chūō Line connecting Tokyo to Nagoya meant it became easier to source seaweed and Nagano saw a peak in kanten production in 1940. It began to stall after that though due first to the intensification of World War II, then later a drop in demand for kanten, along with the aging of the producers themselves. In recent years, the deteriorating environment and soaring costs of raw materials have pushed the industry further into decline.

A Traditional Kanten Production Process

There are currently 13 companies in the Nagano Kanten Manufacturing Cooperative Association. One such company is the long-running Irisen, established in 1942 and based in the city of Chino. We visited their kanten production site, which has remained almost unchanged since they first started operating.

Irisen’s production site (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

The majority of tengusa is imported and this year, Irisen’s supply came mostly from South Korea. Some companies use a type of seaweed called ogonori (Gracilaria vermiculophylla) to adjust how the kanten sets and also to reduce costs. Irisen used to do this too, but now only uses tengusa due to the fact ogonori needs to be treated chemically with acid.

Tengusa that has been loosened up. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

The tengusa is added to the drum in clumps. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

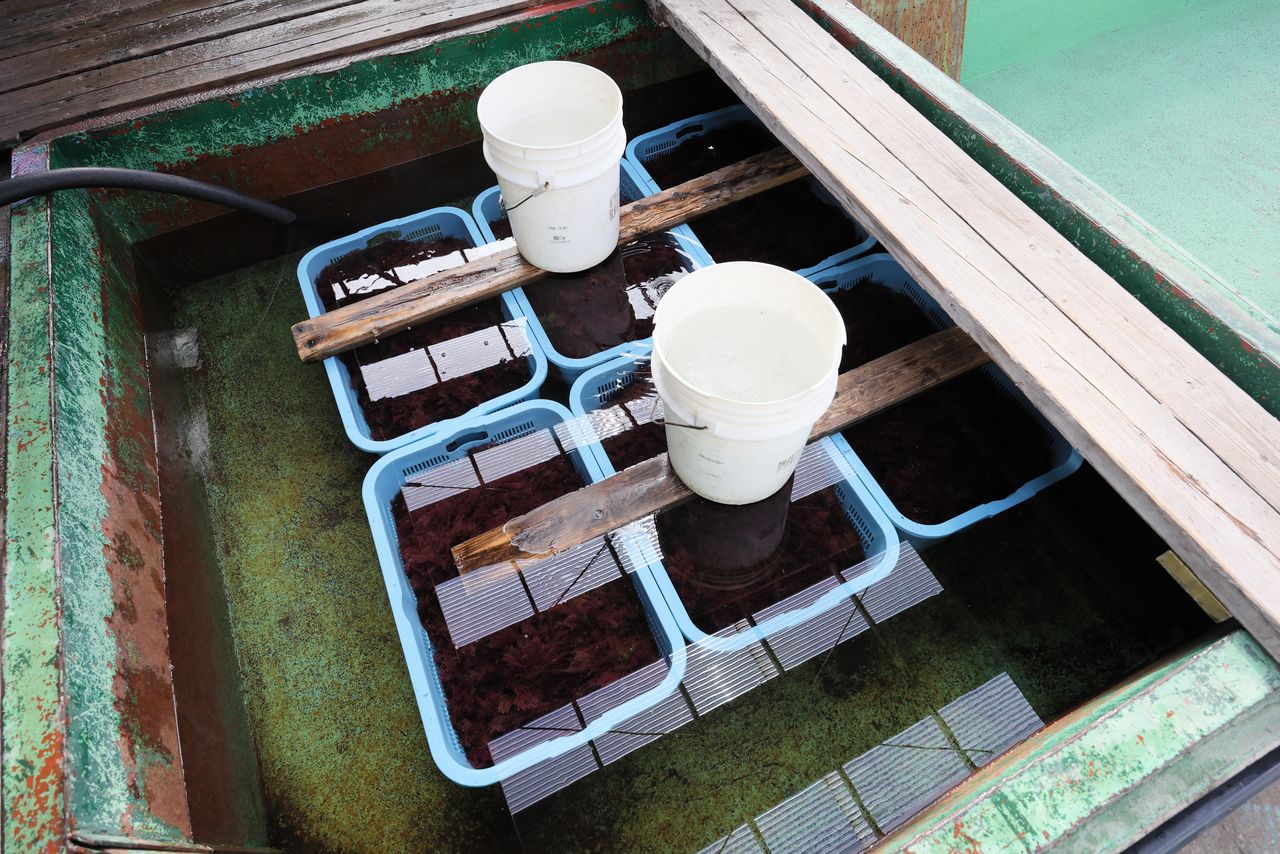

The tengusa is washed in a large rotating drum to remove the salt as well as any foreign objects like grit. This process is called suisha, literally meaning “waterwheel.” After it has been washed for several hours in running water, it is left submerged overnight in a tank of water to remove the scum.

The dirty water is drained through holes in the drum. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

The washed tengusa is collected. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

Weights are placed on top to stop the tengusa floating up. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

A Huge Pot in Action for Eight Decades

The next morning, the soaked tengusa is moved to a huge cauldron-like pot known as an ōgama to undergo the boiling process. This enormous pot is made of iron and, to give it extra height, wooden planks are added around the sides and fixed in place by hoops.

The ōgama pot is 3 meters high and 2.5 meters in diameter. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

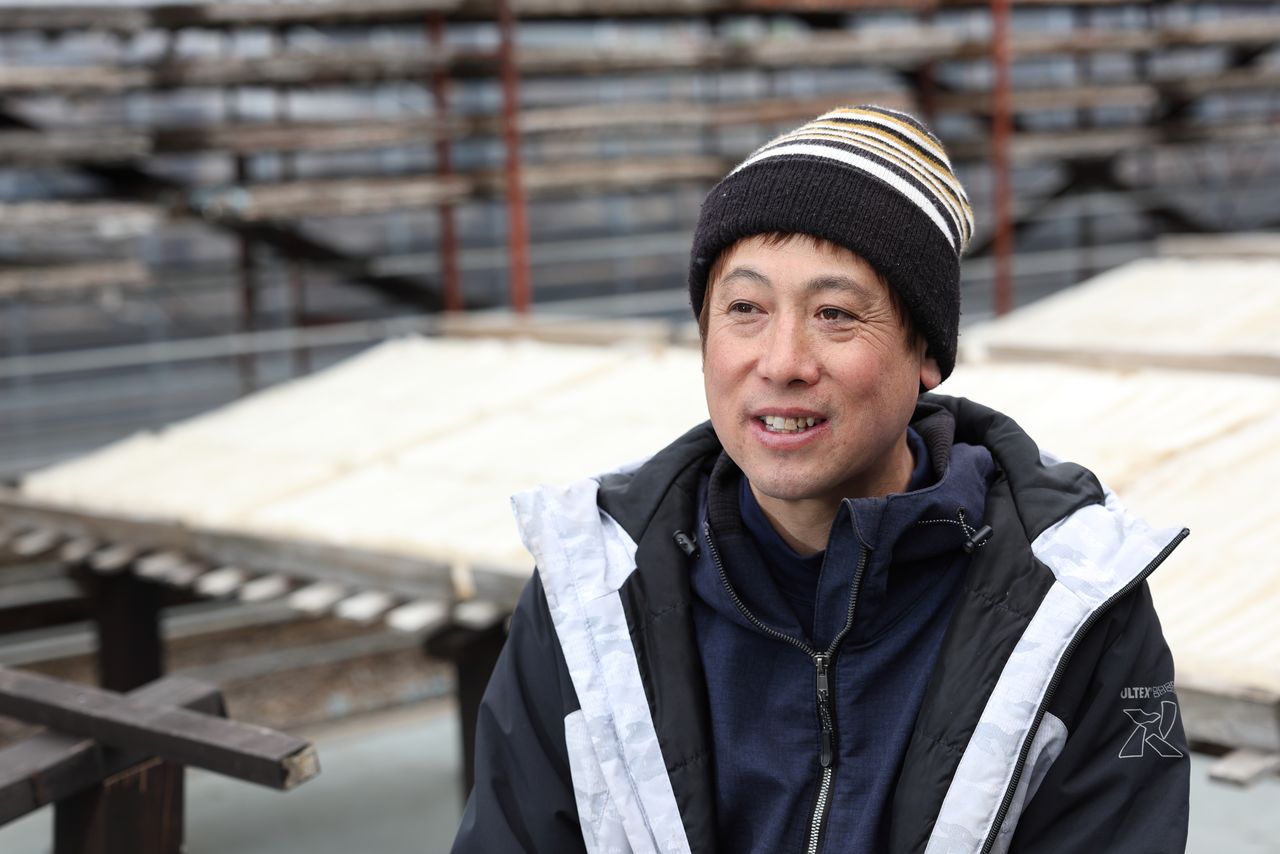

“In summer when the pot isn’t in use, the wood dries out and the hoops become loose. Before use, we soak the wood in water so it expands and stops any leaks. Because it’s been constructed taking into consideration the properties of the wood, even after eighty years of use, the pot hasn’t broken,” explains Chino Fuminori, the fourth-generation president of Irisen.

Chino, Irisen’s president, inspecting the ōgama pot. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

“You don’t need to measure the simmering time as you can tell from the shape of the steam and the color of the smoke from the chimney that it is ready. When you think it’s almost done, you stop the heat.”

The three-piece lid takes two people to open it. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

The necessary ingredient in making kanten is tengusa extract. The liquid is pumped up by a crane-type machine and transferred to a filtering device for straining.

The strings on the bucket are pulled, opening it up so that the contents fall out. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

The extract liquid is poured into tray-shaped containers known as morobuta. The liquid sets as it cools, so it is a race against time.

The liquid is poured into hundreds of morobuta tray containers. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

Chino stated that “at our peak, we were making 10,000 kanten sticks a day and it took three days to wash thirty kilograms of tengusa. It was tough work in the freezing cold. It takes nine hours just to get the water to boiling point in this pot and then it needs to keep simmering for three hours after that, so we were working day and night.”

“In recent years though, demand for kanten has dropped, so that amount of work isn’t needed. We’ve adjusted our process and now make around 2,000 sticks a day. This reduction in working hours has given us a better work-life balance.”

Does this mean business is shrinking? To answer that, we need to look beyond the ōgama pot.

The Value of Participating in the Process

The day after the ōgama process, the namaten (raw tengusa extract), which has now set, is cut into sticks and laid out at a drying station. This work is referred to as the niwa (“garden”). Here the soft yet heavy namaten can crack or corners get broken off, even if handled carefully.

“The amount that can be shipped as perfect sticks is around seventy percent of the total, meaning thirty percent was getting lost in the process. But despite its shape, the quality is still the same. So we intentionally started making shorter kanten, lowered the price, and sold it through our own retail spaces. We found that people who regularly used kanten were happy to buy it. It also made us realize that it doesn’t matter if it has lost its shape,” said Chino.

Misshapen kanten being sold at an Irisen retail space. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

Chino also discovered that even locals didn’t know about the kanten production site. So in 2018, Irisen began running site tours for the general public. In winter, this includes participation in the tendashi process, where the namaten is cut and laid out to dry.

On the day we conducted the interview with Chino, elementary and junior high school students from Suwa were also there to learn about local industry. Following instructions, they went about laying out the cut namaten. Shouts of “it broke off!” followed by replies of “a little bit is fine” could be heard. These participatory tours are possible because Irisen realized that even if the kanten loses its shape, it will still sell.

A comb-like blade is pressed into the kanten and then pulled to cut it. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

The kanten is arranged in wooden frames and at the end the frames are removed. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

What makes the tours popular is that you can try samples after learning about the kanten. Overseas tourists have been participating recently too. Chino explained that “while the factory only operates in winter, we run the tours throughout the year. They’ve actually created regular work.”

What started as a unique experiment has benefited both the kanten producers and consumers, and helped attract tourists to the Suwa region.

Preserving Tradition Through Change

The dried namaten freezes at night due to the cold and then thaws slightly during the day. This is repeated for about two weeks until it has dried completely and turned into white kanten sticks.

A naturally freeze-dried food (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

The effects of global warming have reached the Suwa region too. In recent years, the winters are not as cold and spring has been coming earlier. This has shortened the period in which kanten sticks can be made by around a month.

“We want to keep this original stick shape, but as smaller pieces dry more easily, it makes them better suited to the effects of global warming. In order to protect the industry, we need to be more flexible without getting too stuck on the traditional kanten shape,” stated Chino.

Changes are also occurring at tengusa harvesting locations. We happened to meet with members of the Nishina branch of the Izu Fisheries Cooperative in Shizuoka, who were taking a tour. Shizuoka Prefecture is one of Japan’s largest tengusa harvesting areas, but according to the ama woman freediver Ebata Sonomi, “the amount we gather is decreasing.”

Ebata showing a freediving video. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

“We dive down to three meters, but it’s clear that there is less tengusa than before. The Kuroshio Current has been going off course since 2017 and the growing environment is deteriorating.” Domestic tengusa is becoming increasingly scarce.

Chino pointed out that “rethinking our working style and selling misshapen kanten are both signs of the times.” “It is the same reason for shifting to using just tengusa as the raw material. When we were mixing the boiled tengusa with ogonori and acid, the dirty water was treated as industrial waste. Now we have farmers coming to us, wanting to use the dirty water just as it is for fertilizer. We are getting praised for an improved taste too.” Even though Irisen is producing less, it still want to make good products. The result of following through with this was they were able to create a system of recycling and recirculation.

Chino wants more people to become kanten fans. (© Nomura Kazuyuki)

Chino knows firsthand how good kanten is for your health. When he was 21, he had to stay in hospital for an extended period due to a broken bone, so he often ate his family’s kanten and his blood results showed improvement across the range. “The doctors were amazed at my recovery.” Active in a professional soccer team at the time, Chino was encouraged by this experience to take over the family business. One after another, he puts ideas into action, aiming to reignite an attraction for kanten.

“We have to keep changing to preserve the tradition. I’m going to keep on experimenting,” he explains.

This traditional industry of kanten production in Suwa looks set to continue sustainably into the future.

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting and text by Nippon.com. Banner photo: Bōkanten sticks, also known as kakukanten blocks. © Nomura Kazuyuki.)