Yamasaki Toyoko: Exploring the Author’s Grand Works and Profound Social Influence

Books Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Woman Writer with Osaka’s Warmth

Working for a publishing company, I had the privilege of talking to Yamasaki Toyoko on numerous occasions. The first time I met the author was at her home in Osaka. I was nervous, as I imagined she would be a difficult person, given her painstakingly careful style of writing. From that time onward, though, every time I met her in Tokyo, she would warmly call me by name while taking my hands into both of hers. As I got to know her, I realized that at heart she was a funny, friendly, talkative “Osaka aunty.”

Yamasaki Toyoko was born in 1924 in the merchant town of Senba, Osaka. Her family were merchants specializing in the kelp industry, but she graduated with a degree in Japanese literature from Kyoto Women’s University in 1944 and joined the Osaka bureau of the Mainichi Shimbun, where she worked in the arts and sciences section. There she worked under Inoue Yasushi, who later became a writer in his own right.

Without that encounter with Inoue, it is possible that we would not today know of Yamasaki as a writer. Inoue told her that “a human being can write a masterpiece once in a lifetime, especially if it’s about his or her own home. Why don’t you try it?” She published her first novel, Noren (the title taken from the cloth banner hung above a business entrance), in 1957, about her family’s experiences as kelp traders. She followed this up with Hana noren, an exploration of the founding of a yose entertainment group. Hana noren was serialized in Chūō Kōron, a major literary and opinion magazine in Japan. For this, Yamasaki won the thirty-ninth Naoki Prize, awarded twice a year to the best work of popular literature. The award-winning style hinted at in these novels would define her novels throughout her career.

In essence, Yamasaki’s approach was to research for half a year, followed by half a year of writing. She told me: “I never set out to write a complex novel like a bonsai practitioner pruning lots of refined branches at the same time. My approach is closer to that of someone who plants trees one at a time on a barren mountainside.”

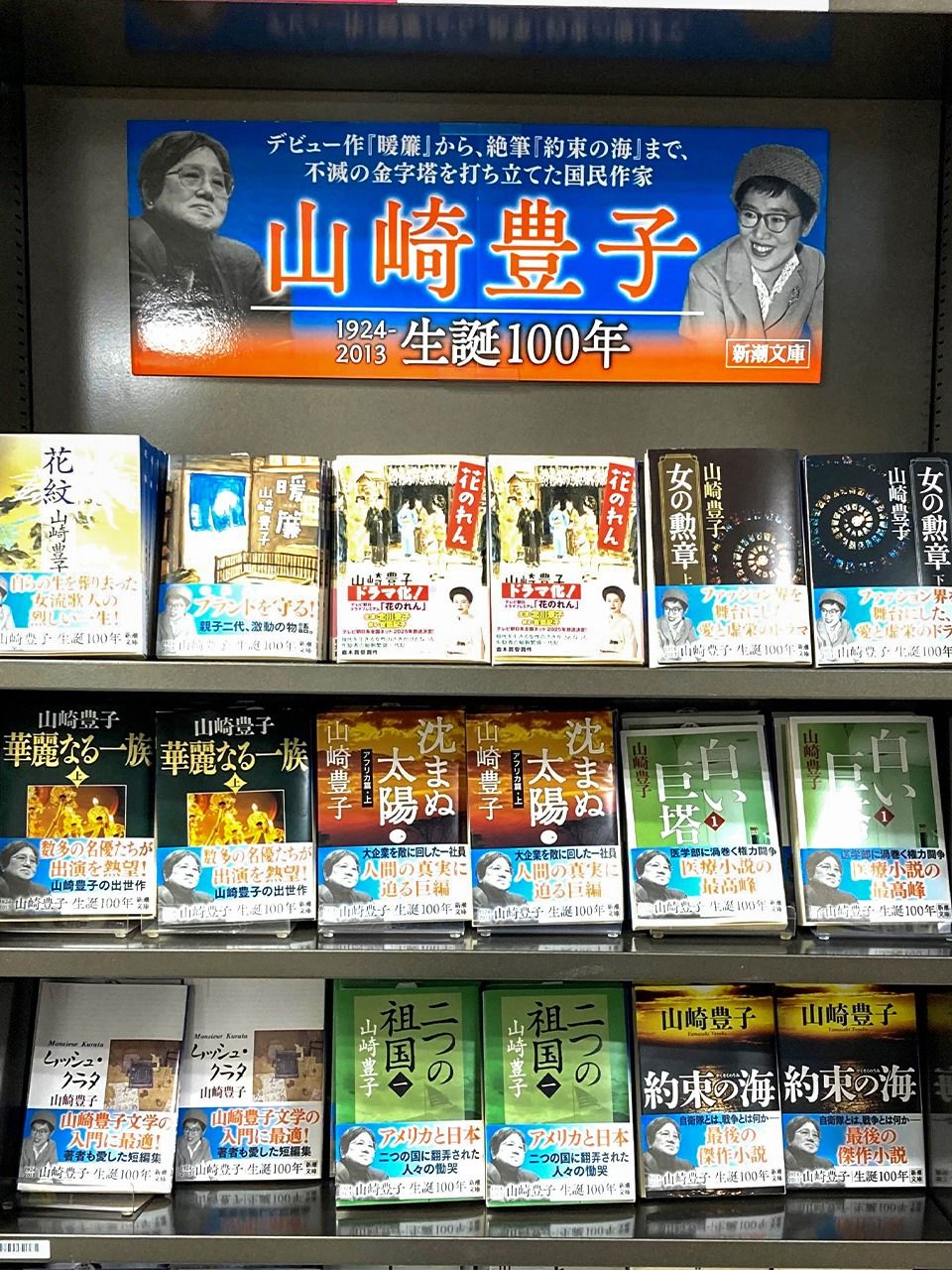

A Tokyo bookstore display features Yamasaki Toyoko’s works to mark the centennial of her birth. (© Nippon.com)

It was Shiroi kyotō (The White Tower) that solidified Yamasaki’s status as the “socially aware” writer that she is known to be today. Serialized in the weekly magazine Sunday Mainichi beginning in 1963, the story follows two classmates who are now associate professors at Naniwa University Hospital in Osaka. Through the characters of the ambitious Zaizen Gorō (Department of Surgery), and the conscientious Satomi Shūji (Department of Internal Medicine), Yamasaki sharply examines the problems of corruption over promotions and personnel and medical errors in the hospital. Shiroi kyotō generated a significant social response; following its 1965 book publication it was subsequently made into a 1966 film, while also being remade for television in Japan five times and once in Korea.

Yamasaki never particularly liked the “socially aware” label. She told me that “my character doesn’t allow me to ignore the problems of the marginalized, and I can’t tolerate absurdity in the powerful. It just so happened that when I wrote about my thoughts on these things they took on a social significance.”

However, the sheer intensity of the response clearly attuned Yamasaki’s gaze toward social issues. Her next major work, Karei naru ichizoku (The Grand Family), took on the cutthroat worlds of industry and finance and the sacred banking sector. Serialized in a weekly magazine from 1970, it was published as a novel in 1973 and subsequently adapted into a film and, on three occasions, into a television series.

The story is about Manpyō Daisuke, the president of Hanshin Bank, and the head of a leading business empire in the Kansai region. In the postwar era of restructuring and business turmoil, he aggressively wields the power of his zaibatsu to create mergers where the “small swallow up the large.” However, Daisuke’s eldest son Teppei, who is the managing director of an affiliated steel company, has a strong sense of justice and his own interests. He constantly feuds with his egotistical father, and against the background of family secrets, the relationship leads to catastrophe. According to Yamasaki, Karei naru ichizoku was about three types of evil that haunt society: “bedchamber politics, corporate skullduggery, and bureaucratic misdoings.”

Shining a Light on Human Realities

The appeal of Yamasaki’s works is their strong sense of realism and attention to detail. Backed by meticulous research, each novel was based on a prototype character—which often led to speculation about whom Yamasaki was modelling her characters on. However, she once told me: “If I just used a real person as the protagonist without changing anything, there would be no need for me as a writer to go through the process of creation.”

Therefore, the characters were unique in detail and reflective of Yamasaki’s own point of view. “Just listing facts obtained through interviews doesn’t make for an interesting novel. We must use the details to form a human drama through composition and our imagination as writers. It is through this that we can explore the reality of humanity.”

Yamasaki thoroughly researched each subject until she was satisfied with the findings. She wrote down the progress of a story on a large piece of paper in chronological order, following the main characters until the end of the narrative. Only when the overall concept had come into her full view did she begin to write.

Yamasaki also shared with me the difficulty of finding a title that reaches out and captures the reader: “The title summarizes the very theme of the work. I like to use juxtapositions. For example, Futatsu no sokoku [trans. by V. Dixon Morris as Two Homelands] was ultimately about one homeland, while Shizumanu taiyō [The Never-Setting Sun] was really about the end of the line for some, and renewal for others.”

A Writer Born from War Experience

According to Yamasaki herself, the origins of her interest in writing can be found during her youth and her experience of war. During World War II Yamasaki worked in a munitions factory polishing bullets. One day she became unwell, and while resting, was caught reading a foreign novel. This resulted in her being beaten by a supervising military officer. As Yamasaki once wrote, “in reality, I had no youth.”

Yamasaki once discussed how “the men were put in suicide planes to go die in the clouds, while the girls were mobilized in our second year of college to work in the factories. Some of my friends who worked in an airplane factory were killed by bombs from a B-29. As a survivor, I have always wondered what I should do with the life I was allowed to hold onto.”

That was the genesis for a trilogy of novels about war. The first novel in the trilogy, Fumō chitai (trans. by James T. Araki as The Barren Zone), began serialization in 1973. Iki Tadashi, a former operations strategist in the Imperial General Headquarters, is interned in a prison camp in Siberia after the war. Surviving the harsh conditions there, upon his eventual return to Japan, he is appointed to head up a trading company, where he engages in a fierce rivalry with a cometing firm.

While Japan had regained affluence following its wartime catastrophe, Yamasaki had misgivings about its spiritual development. The main character of the novel therefore represents the changes and progress of Japan from the war up through the era when she wrote him—but her work also details how the protagonist navigates the spiritual “barren zone” that Japan had become.

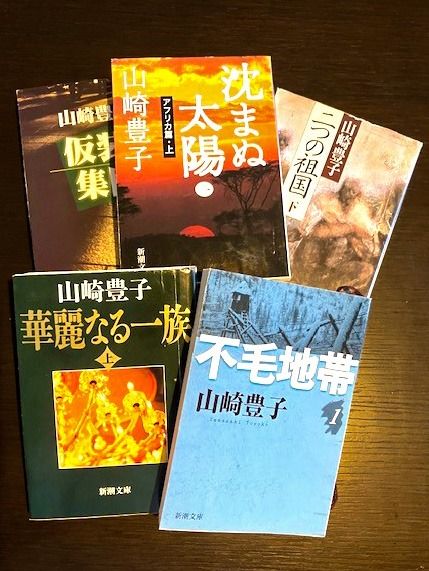

Yamasaki’s novels are touchstones for generations of readers who encountered them in the postwar era. (© Nippon.com)

Two Homelands (serialized from 1980) depicts the tragedy of Kenji Amō, a second-generation Japanese American living in Los Angeles. As the Pacific War unfolds, and then the postwar Tokyo Trials take place, Kenji is torn between the “two homelands” of the book’s title, Japan and the United States. The work is particularly ambitious for Yamasaki’s incorporation of four themes: the internment of Japanese Americans, the battles in the Philippines, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and the Tokyo Trials. Yamasaki reflected on how through these events, the hearts of Japanese were being eaten away at and they were losing their “natural love for the country of birth and homeland.”

In Daichi no ko (Children of the Earth), Yamasaki explores the tragedy of Japanese war orphans abandoned in China after World War II in a novel that began serialization in 1987. The main character is a Japanese war orphan, Lu Yixin, who was brought up by a Chinese philanthropist and eventually becomes an excellent engineer. Buffeted harshly by the postwar tides of Chinese politics, he suffers greatly during the Cultural Revolution in particular. Lu later recovers his social standing and starts to work on a joint Sino-Japanese steel plant project. Even here, however, he is at the mercy of changes in Sino-Japanese relations. Ultimately, the reunion of Lu with his real father marks the beginning of the work’s central part.

What makes this novel a particular pleasure is its depiction of the lives of the Chinese As and the realities of their life under the Chinese Communist Party. Like with all of Yamasaki’s work, this was based on painstaking research. Her encounter with the CCP’s General Secretary Hu Yaobang enabled her to visit poor farming villages and steel mills in undeveloped areas of China normally off-limits to foreigners. The “fleeting spring” of the positive Sino-Japanese relations in the 1980s and more open relations between China and the world were great enablers of Yamasaki’s publication.

Faith in What Tomorrow Brings

Yamasaki spent eight years writing Children of the Earth, and on its completion, she realized she had run out of energy and was spiritually exhausted. To reward herself, Yamasaki decided to realize a childhood dream by visiting Kilimanjaro, the highest peak in Africa. She got in touch with a local representative of Japan Airlines and asked to be guided to Nairobi, the capital of Kenya.

During that time, the JAL official shared tales of his difficult career with her. He was chairman of the JAL labor union in the past, and in retaliation for precipitating tensions with management, he had been “exiled” from Japan and had to endure long periods of time away from his family working in places like Karachi, Pakistan, Tehran, Iran, and Nairobi.

Yamasaki was actually thinking about retiring from writing at the time, believing that she would struggle to write something that surpassed Children of the Earth. The curious nature of a writer would not allow this, however, and Yamasaki dug deep into her newly found story and produced The Never-Setting Sun.

Other events colluded in pushing Yamasaki to put off retirement and pursue this story. She went to see a trusted colleague who was an editor at a publishing company and had now become a senior executive. She was told that “writers do not retire. They write even when they are being loaded into the coffin at their funerals.” Feeling his time of death was approaching, the executive then asked Yamasaki whether she could write something that would serve as an offering at his funeral. Yamasaki laughingly told me: “How could I refuse such a request? That is quite a thing to ask of someone!”

The Never-Setting Sun was ultimately based on the worst aviation disaster in history—JAL Flight 123, which crashed in Gunma Prefecture in August 1985 and killed more than 500 people. The novel’s protagonist is Onchi Hajime, who returns to an airline’s headquarters following a long period working as an overseas transfer. As soon as he returns home, disaster strikes on Mount Osutaka in Gunma. An external executive is brought in to become chairman and rebuild the airline company’s management following the disaster. However, an ugly power struggle erupts, and Onchi becomes a central player as an assistant to the new chairman.

Onchi is portrayed as someone who never bends the rules, even at the expense of company profits. The title was inspired by the sunsets Yamasaki witnessed in Africa. She recounts how she felt that “no matter what adversity we face, we must keep the sun that never sets in our hearts. We should live our lives with faith in what tomorrow brings.”

Yamasaki indeed wrote until the end of her life. In 2013, she was working on a novel called Yakusoku no umi (The Promised Sea) that began serialization in the Shūkan Shinchō magazine. However, only one month after the publication of the initial installments, Yamasaki passed away. While serialization continued, the story remained incomplete.

The Yamasaki Toyoko I knew was a solitary person who was outraged by unreasonable things in the world. She was not that interested in becoming involved in the wider literary sphere and devoted herself solely to her manuscripts. In my view, no other writer has risen yet to surpass her grand and profound style.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 11, 2024. Banner photo: Yamasaki Toyoko giving an interview in 2003. © Kyōdō News.)