One Hundred Tales: Stories of Japan’s Cute and Creepy “Yōkai”

Culture History Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The COVID-19 pandemic forced cancelations of festivals and firework displays in Japan this summer, but one traditional custom survived, albeit in altered form. Haunted house attractions are meant to counter the heat of the season with the chills of a good scare. Summer 2020, however, saw socially distanced drive-in haunted houses and real-time horror experiences delivered via Skype and Zoom.

Yumoto Kōichi, a researcher of yōkai (supernatural spirits and monsters), says Japan has an unbroken tradition of culture based on appreciating the thrills of terror that dates back to the Edo period (1603–1868). At this time, hyaku monogatari (100 tales) collections were hugely popular at every level of society, whether as books or at storytelling gatherings. They are based on a legend about lighting a number of candles and putting them out, one at a time, after telling each of a series of frightening tales. When the final candle is extinguished, and the listeners are plunged into darkness, it is said that something strange and terrifying will happen.

While the origins are unclear, they are believed to derive from tests of courage for samurai in the Muromachi period (1333–1568), which later spread among the common people as a pastime in the Edo period.

A Sense of Reality

“They called them ‘a hundred tales,’ but they didn’t necessarily tell that exact number of scary stories,” Yumoto says. He explains that in the same way that a phrase like yaoyorozu (written 八百万, meaning 8 million) in Japanese simply indicates a huge number, 100 just meant “many stories.” Of the various collections like Shokoku hyaku monogatari (One Hundred Tales from Many Lands; 1677) and Otogi hyaku monogatari (One Hundred Fantastic Tales; 1706), with the number in their titles, only the first actually contained the number of tales indicated.

Katsushika Hokusai, Hyaku monogatari: Sarayashiki (One Hundred Tales: Dish Mansion). (Courtesy Miyoshi Mononoke Museum)

“It wasn’t possible to distribute large numbers of handwritten books, so the widespread adoption of woodblock printing helped drive the popularity of the ‘hundred tales’ collections. Ghostly pictures on hanging scrolls attracted participants to gatherings, and artists like Katsushika Hokusai also took on the theme in colored woodblock prints.”

What kind of stories were included in collections?

“Rather than tightly constructed narratives,” explains Yumoto, “they mimicked gatherings with stories playing up personal connections to the tellers, like ‘this tale has been passed down in such-and-such a location’ and ‘I heard this from a certain somebody.’ In this way they put together stories based on what participants said they had seen and heard. The preface to One Hundred Tales from Many Lands drew in readers through claims to authenticity propped up by details of who had experienced the events and where.”

From the third volume of One Hundred Tales from Many Lands. The wife of a man called Abe Sōbei dies of sickness after he treats her badly, and returns as a spirit to wreak her revenge. (Courtesy Center for Open Data in the Humanities)

Said to be the original hyaku monogatari collection, One Hundred Tales from Many Lands consists of five volumes with stories from Tōhoku in the north to Kyūshū in the south. Around a third of the tales concern ghosts, often of the jealous, vengeful type. For example, the ghost of a first wife who died while giving birth returns to confront the successor who cast an evil spell against her, and rips her head off. Other stories feature strange monsters or are about uncanny animals like snakes, foxes, tanuki (raccoon dogs), and cats.

“Today’s urban legends are told as if they really happened, but in the information age, if we hear that something happened in a particular place, we can check online or go there ourselves. In the Edo period, though, the masses almost never left the place they were born. If people got together and someone said, ‘This happened in Tōhoku . . .’ there was no way of checking, which heightened the sense of reality, and all the listeners got a kick out of exercising their imaginations.”

Part of Ehon hyaku monogatari (One Hundred Tales Picture Book), published in five volumes in 1841. The picture shows the “bean washer,” a former priest killed by a wicked comrade, who became a spirit in Takada, Echigo (now Niigata Prefecture). He appears at night, washing azuki beans in the river. As an expert counter in his lifetime, he is said to know the exact number of beans just by washing them. (Courtesy Miyoshi Mononoke Museum)

The Haunting of Heitarō

The hyaku monogatari tradition inspired modern and contemporary writers like Lafcadio Hearn, Mori Ōgai, and Kyōgoku Natsuhiko. It also played a big role in the story of a legendary historical haunting known as the Inō mononoke roku (Inō Spirit Record) in the city of Miyoshi, Hiroshima Prefecture, in which a young samurai was visited by a series of yōkai.

The story goes that throughout the seventh month (by Japan’s former calendar) of 1749, 16-year-old Inō Heitarō of Miyoshi was plagued by great numbers of strange creatures and phenomena day and night, but got through the ordeal unscathed. According to the record, Heitarō’s performance of the hyaku monogatari with a friend, putting out the candles one by one, was the trigger for this unwelcome carnival of spirits. He is said to have passed on the story of his younger days when he later went up to Edo (now Tokyo) to work in the domain lord’s residence there.

“This story spread beyond the local area in the form of picture scrolls, handwritten books, and picture books. As they were completed by hand, it wasn’t possible to make hundreds of copies, but readers could borrow them from booklenders, so it’s likely that many people read them. Some of the yōkai in picture scrolls made a powerful impact, while others were childish or cute.”

The parade of yōkai included a severed woman’s head that walked around upside down, using its hair as legs and shrieking with laughter, as well as a giant, old woman’s head that hung from the ceiling and licked the sleeping Heitarō on his face. The Edo period scholar Hirata Atsutane took an extraordinary interest in researching the story, while writers like Izumi Kyōka were also fascinated and used it as a motif in their works.

Detail from the Edo-period Inō mononoke roku emaki (Inō Spirit Record Picture Scroll), said to record the strange events of the first day of the seventh month of 1749. On the left, Heitarō is caught by a giant, who appears at the wall. His friend Gonpachi, who also joined him in the ordeal, receives a yōkai visit at the neighboring house on the right. (Courtesy Miyoshi Mononoke Museum)

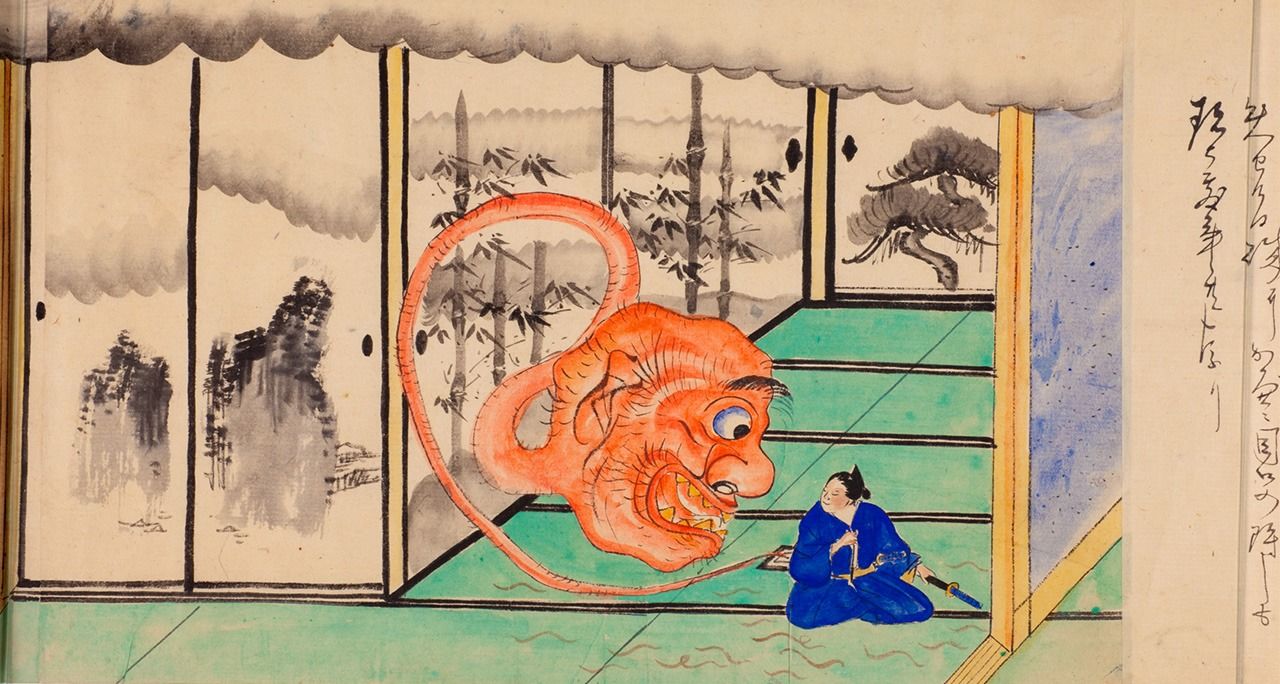

Detail from the Meiji era (1868–1912) Hyaku monogatari emaki (One Hundred Tales Picture Scroll). Modernizing Japan saw no end to works depicting the Inō Spirit Record. This example shows the creature that came on the thirtieth of the seventh month. It is a yōkai made of ash that appeared from the building’s hearth. Many worms are also crawling through the room. (Courtesy Miyoshi Mononoke Museum)

Creepy and Cute

Yōkai were born from people’s fear of nature and darkness. Yumoto says, “Edoites had finely tuned antennae to what might be squirming in the gloom. Even on the city streets there was almost no light after dusk, so darkness was a familiar presence. Without traveling very far, a number of chilling rumors could arise in neighborhood communities.” There were collections of nana fushigi or “seven mysterious stories” associated with different parts of the city like Honjo, Kōjimachi, and Azabu.

In the Edo period, fear of the weird was there alongside a view of yōkai as cute and friendly denizens of the neighborhood. This latter feeling was fueled by the endearing depictions of them in picture scrolls and woodblock prints.

“The widespread use of woodblock printing made it possible for anyone to cheaply acquire yōkai pictures, so they became quite familiar. As more people lost their fear of yōkai, there were more cute pictures of them. In line with the growing popularity of the hyaku monogatari, yōkai began appearing in kimono patterns, miniature netsuke sculptures, and children’s cards and games.”

Karuta cards with yōkai from the Edo period and later. (Courtesy Miyoshi Mononoke Museum)

Adapting to the Times

Yumoto says Japan’s yōkai culture could draw on a particularly great variety of sources. “There were adapted Chinese tales and Buddhist stories, but tellers didn’t limit themselves just to these—the incorporation of animistic elements was also notable. Perhaps the best example of the latter is the development of the idea of tsukumogami, or objects that acquire a spirit after a number of years have passed. Anything can become such a yōkai, and there are all kinds of pictures of them.”

The Meiji era (1868–1912) saw such objects as rickshaws, lamps, and Western-style umbrellas joining the yōkai ranks. With the introduction of railways and steam trains, there were stories of tanuki transforming themselves into locomotives, while the advent of cameras prompted accounts of ghosts appearing in photographs.

“Stories of strange happenings persistently adapt to changes in the times and society, and live on. And simultaneous feelings of fear and familiarity toward yōkai are still found today. Every summer, when horror specials are broadcast on TV, there must be viewers scared to go to the toilet alone, while clutching mobile phones with cute yōkai charms hanging off them.”

Even if the present yōkai boom was sparked by the popularity of manga by Mizuki Shigeru and horror fiction by Kyōgoku Natsuhiko, Yumoto comments that they needed the longstanding cultural roots.

He says that most Japanese people have a mental image of creatures like kappa, oni, or tengu. “This isn’t something they learn from their parents or teachers—it comes from the yōkai culture dating back to the Edo period that everyone inherits. It’s because of this culture that Mizuki’s Kitarō became such a popular character. As some are inspired to draw yōkai manga by Mizuki and others to research yōkai, the base expands, and the culture is passed down.”

Spreading the Word

In April 2019, the Miyoshi Mononoke Museum opened in Miyoshi, Hiroshima Prefecture, where the haunting of Heitarō the samurai is said to have taken place. The institution is also known as the Yumoto Kōichi Memorial Japan Yōkai Museum, as the core of its holdings is Yumoto’s collection of books, picture scrolls, toys, and other yōkai-related items accumulated over 30 years.

“There have been some movements to build foundations for yōkai research, such as the construction of a yōkai database at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, but I wanted to separately make a museum dedicated to yōkai. Right now, there’s a danger that materials not being used in research will be forgotten. At the same time that research is taking place, there needs to be a specialist museum to preserve materials for future generations. It can’t just be a facility for boosting local tourism. It has to be a place where expert staff see the importance of looking after materials for posterity, so they think about issues like humidity and lighting when the items are on display or in storage, and repair them when necessary. It also needs to be a place where people can conduct research.”

Yumoto is also enthusiastic about sharing yōkai culture with the world. At events celebrating 150 years of diplomatic relations between Japan and Spain in 2018, part of the Yumoto collection was exhibited at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. He is planning an exhibition that will go on display in a number of countries in 2021.

“I want people across the globe to see how fascinating Japan’s unique yōkai culture is. Manga has become a word that is known internationally, and yōkai is moving in that direction.”

(Originally published in Japanese on September 14, 2020. Interview and text by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Banner illustration: Detail from the Meiji-period two-volume Hyaku monogatari emaki (One Hundred Tales Picture Scroll) by Hayashi Kumatarō. Courtesy Miyoshi Mononoke Museum.)

Related Tags

ukiyo-e Hokusai yokai folklore ghosts horror ghost stories legends