“Mononoke” Movie Brings Anime to Theaters 17 Years After TV Hit

Cinema Anime Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Mononoke, Reborn

The series Mononoke takes its name from spirits that bind themselves to powerful human emotions. The Medicine Seller, protagonist of the series, possesses a sword capable of quelling them. However, in order to wield it, he must discover the form, truth, and reason of each mononoke—its original human name, what caused it to turn, and the reason for its emotional turmoil.

The 2007 animated television series Mononoke laid the groundwork for the story.

The anime’s stylish look incorporates motifs from ukiyo-e prints and washi paper for a distinctively Japanese taste, with scripts utilizing horror and mystery as the backdrop for evocatively rich human dramas. The series enjoyed great popularity during and after its broadcast run, and found no shortage of fans abroad.

The protagonist, the Medicine Seller, symbolizes the ethos of the Mononoke series. (© Twin Engine)

A crowdfunding campaign for Gekijōban mononoke: Karakasa (Mononoke the Movie: The Phantom in the Rain) launched in 2022, on the fifteenth anniversary of the series’ original broadcast. It quickly blew past the minimum ¥10 million to raise ¥60 million in funding for the film’s production.

The movie’s director, Nakamura Kenji, also worked on the television series. “To be honest, at first I did not have high hopes that a film would be made,” he is reported to have said—the reason being that the world had changed greatly since the series first aired in 2007.

“In 2007 the iPhone went on sale in Japan. It was also the year that Twitter started, the year that the world began to profoundly change. At the time, social media had yet to take off, and it was difficult for individuals to make themselves heard. Mononoke was created as a kind of lifeline for the ‘unheard masses.’”

The Medicine Seller’s sword. (© Twin Engine)

The series showcased many mononoke, which is an old word for the more commonly used yōkai, monsters from Japanese folklore. Old favorites such as bakeneko (phantom cats), zashiki warashi (ghostly kids), umi-bōzu (monstrous “sea-monks”), nopperabō (“faceless ones”), and nue (chimaeras) all made appearances. In the series lore, they are born from the emotions of people: love and greed, loneliness and despair. The Medicine Seller uses his sword to quell the spirits of those whose unjust treatment in life led them to turn into mononoke in death.

“If anything, there’s an overflow of human emotion in the world today, as seen in the popularity of social media. So the original concept of blocked emotions felt as though it wouldn’t convey as it had before. I worried that the times weren’t right to support the creation of a new Mononoke.”

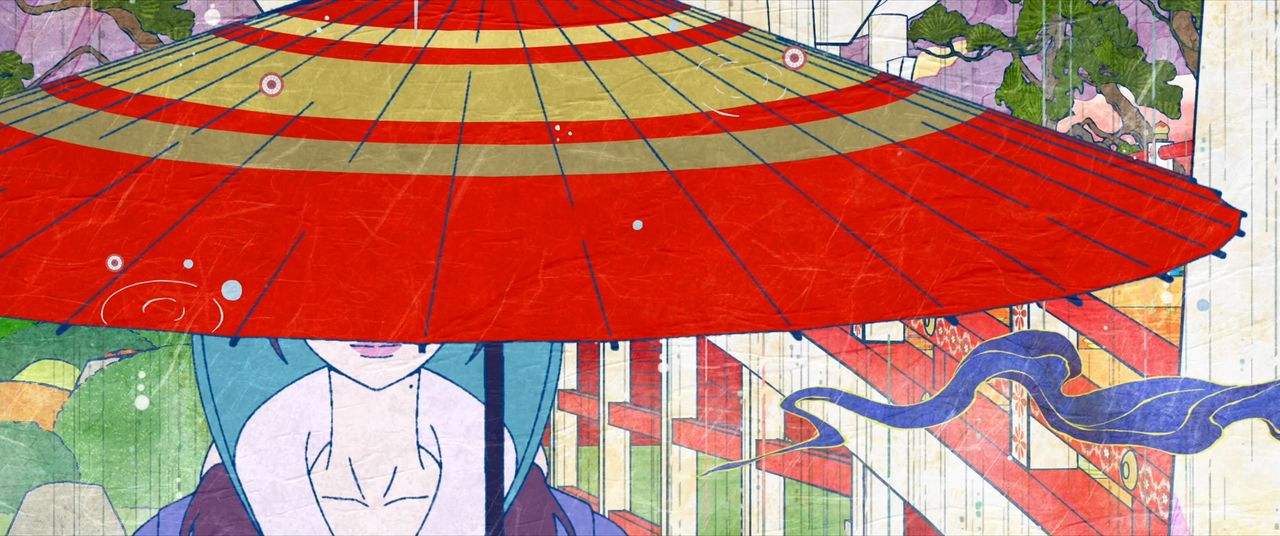

The film’s main mononoke is karakasa, a phantom umbrella. (© Twin Engine)

“If we were going to make a new version, we wouldn’t compromise,” said Nakamura. He read through numerous story ideas to come up with one he felt would resonate with modern audiences, then spent two years developing the script.

The Idea of a Group Grudge

After much trial and error, Nakamura became interested in the theme of the “fallacy of composition.” This is an economics term that refers to the mistake of inferring that an action that produces a positive result for an individual or an organization will not always be positive and successful from a broader perspective.

“The thinking of groups and individuals will always go out of sync—that’s been true since times of old, still is today, and will be so long as society is composed of emotional creatures, which is to say people,” says Nakamura. “I felt that if I could portray the negative emotion from that schism fueling a mononoke, it would give it a sense of reality for our current moment. Until now, I focused on the emotional turmoil of individuals, but this time I wanted to show what a society in emotional turmoil might look like.”

Maidservants in the inner chambers of the imperial palace. (© Twin Engine)

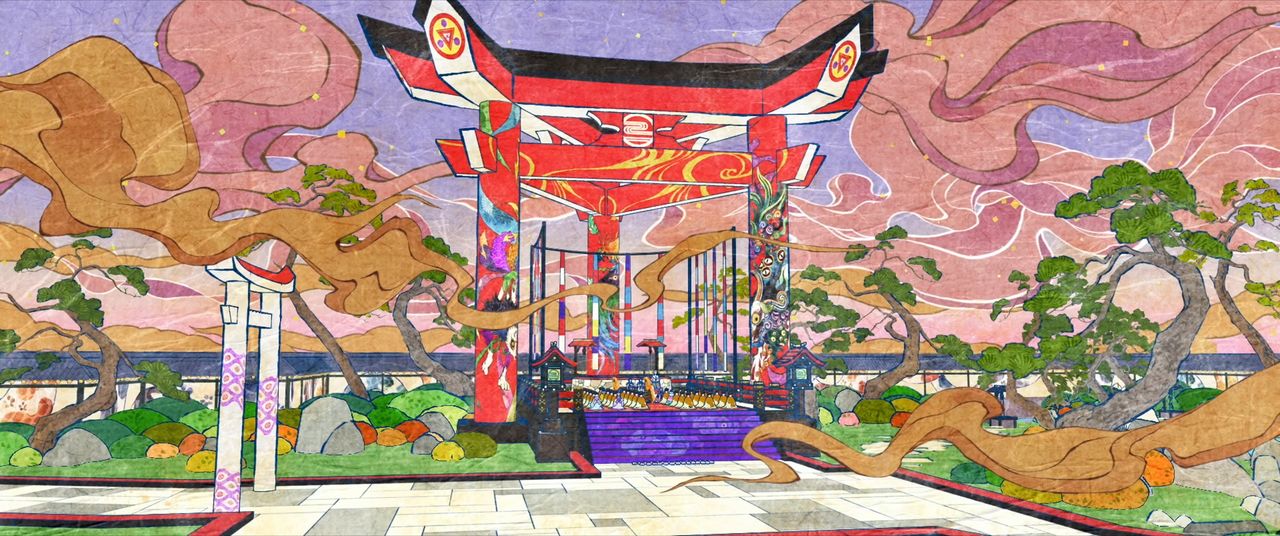

The setting of this new story is the ōoku of the Imperial palace. These “inner chambers” house a cloistered group of women who tend to the emperor’s needs—and serve as concubines, competing among themselves to produce an heir for him. This is a special place filled with the most beautiful women from across the land, and totally forbidden for any man besides the emperor to enter. This gives it great political influence, almost like a wing of the government.

“The ōoku is visually appealing, and fits well with the concept of mononoke. And, as it turns out, it also fits well with the theme of ‘the fallacy of composition,’” says Nakamura.

Two new arrivals. The talented Asa (above) strives to rise through the ranks quickly; the innocent Kame is clumsy and prone to mistakes. (© Twin Engine)

The plot centers on the appearance of a mononoke called the Karakasa, triggered by the arrival of two new faces in the ōoku, Asa and Kame.

Asa leverages her intelligence to work efficiently, quickly accustoming to life in the inner sanctum. Kame, on the other hand, yearns to fit in, but her clumsiness makes her resentful of those around her. Although opposites in nature, they soon form a special bond. Meanwhile, Utayama, who holds the highest position in the ōoku, is hiding a secret. Strange phenomena begin to occur, throwing the ladies into turmoil.

Utayama, leader of the ōoku. She treats those beneath her well, out of a desire to foster and support the inner chambers. (© Twin Engine)

A New Protagonist

Produced 17 years after the televised series, the film adaptation takes a different look and feel. While the imagery still looks like that of an antique picture-scroll, the character design was entrusted to manga artist Nagata Kitsuneko, who revamped the visuals of the Medicine Seller, along with his sword, scales, and medicine chest.

As in the television series, the Medicine Seller is a cipher, whose background and even personality are cloaked in mystery. But he is a different person than that of the television show.

The director believed the character fundamental to the series and never considered using another protagonist. Nakamura wanted to “maintain the feel of the character from the TV version, even though he was a different person,“ and spent more than ten months redesigning him.

In Nakamura’s words, the new Medicine Seller is “seemingly cool and detached, yet unafraid to venture into a maelstrom, and passionate about saving others.” (© Twin Engine)

Aware of the show’s growing popularity abroad, the staff redoubled their efforts to emphasize the Japanese imagery of the production. For the film, they incorporated even more motifs from ukiyo-e prints and Japanese art.

“It was a delicate balance, stylizing Japanese imagery without taking it too far. Ukiyo-e prints are flat, with sharply delineated backgrounds. Mononoke uses this visual sense, setting it apart from any other anime. We also took pains to keep the imagery from being too flashy.”

The visuals evoke washi paper and ukiyo-e prints. (© Twin Engine)

The use of textures from Japanese paper represents another unique technique. Real Japanese paper was used as a screen filter. But the palette differs from ukiyo-e in subtle ways. The glamorous setting of the ōoku chambers features more saturated colors in comparison to that of the TV show, creating a vivid picture of the sort favored by foreign audiences.

A doll featuring at the crux of the story. (© Twin Engine)

The Essence of Mononoke

The changes in society in the 17 years between the TV series and film are reflected in its tone.

“The TV series was made at a time when the future still seemed bright, so we aimed to portray dark stories,” explains the director. “Now we live in a dark age, with an uncertain future, and there is no shortage of dark stories on social networking sites. There is no need for more darkness, even in an entertainment sense. That’s the biggest reason why this series has changed so much.”

Saburōmaru, charged with investigating the incidents inside the ōoku. (© Twin Engine)

So times have changed. But what is the fundamental, unchangeable essence of the Mononoke series?

“The most important aspect is the presence of the Medicine Seller. Then, the stories of the realities of emotional turmoil. It’s important to make viewers feel that reality, when the Medicine Seller quells a mononoke with his sword. It’s fiction, but I wanted to portray something that felt close to reality.”

Mugitani, a “big sister” to the rest of the ōoku. (© Twin Engine)

Also unchanged from the television series is the overwhelming amount of audio-visual information onscreen.

“People tend to seek out easy-to-watch entertainment today,” reflects Nakamura. “But sometimes, it’s good to watch something that makes you think. I wanted to portray the story in a fast-paced, compelling way to give it the rhythm that modern audiences demand, but I wanted to take time developing those events, to give them complexity.”

A world where everything onscreen means something. (© Twin Engine)

Perhaps the biggest surprise of Mononoke the Movie: The Phantom in the Rain came after its release, when it was announced that it was the first outing in a trilogy to come. The second film, Hinezumi (Fire-Rat), is scheduled for release in March 2025.

Says Nakamura: “There isn’t a single character in the film that isn’t important to the story to come. The stories of many side characters will come to life in future installments.”

The story of the new Medicine Seller is only beginning.

The Medicine Seller faces off against Karakasa in a battle scene. (© Twin Engine)

Official Trailer

Official website (in Japanese): https://www.mononoke-movie.com/

(Originally published in Japanese. Text and interview by Inagaki Takatoshi. Banner image from Mononoke the Movie: The Phantom in the Rain. © Twin Engine.)