A Walk around the Yamanote Line

From Ōsaki to Tamachi: Exploring the Southeast of Tokyo’s Yamanote Loop

Travel Guide to Japan- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Old and New at the Southern Tip of the Yamanote

Our walk along the Yamanote Line starts at Ōsaki Station, the loop’s southern tip and one of Tokyo’s recently redeveloped districts. This is a part of Tokyo foreigners hardly get to see. And why should they venture here anyway? That’s, I guess, the difference between a casual tourist and a dedicated traveler, or urban explorer: The latter finds interesting things where other people only see the mundane, the banal.

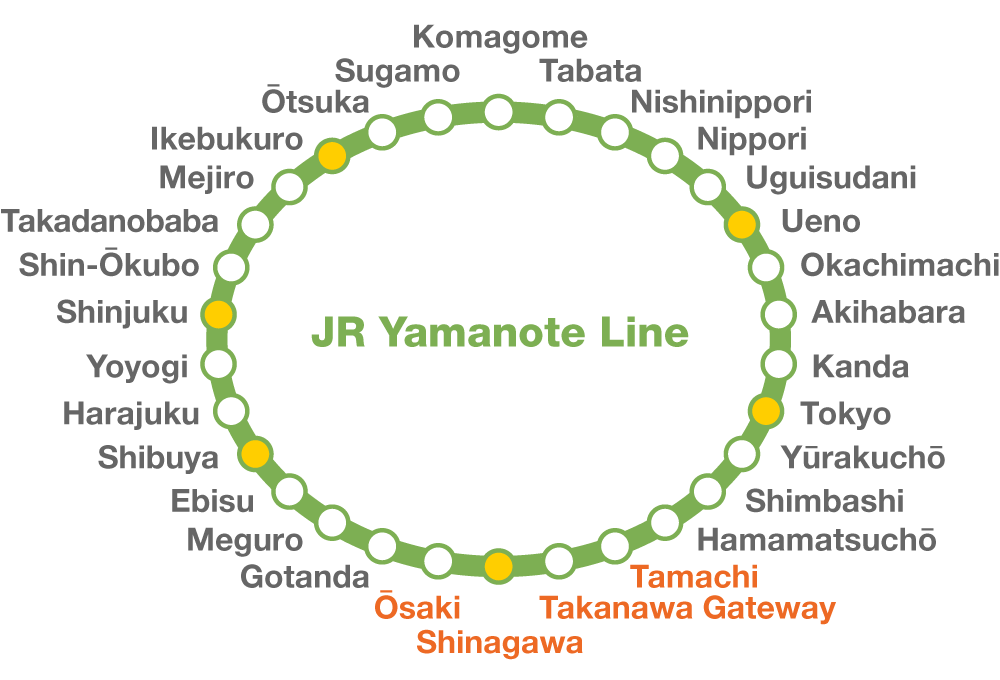

The stations on the Yamanote line stations loop. (© Pixta)

Walking around Ōsaki New City, this new mixed residential-commercial project feels like stepping into one of those promotional videos where building companies advertise a new paradisiacal urban enclave. It appears both surreal and exhilarating.

The banks of the Meguro River near Osaki have recently been redeveloped. (© Gianni Simone)

While the station is surrounded by a forest of shining high-rises, though, you only need to climb the nearby hill to reach sights from an older age: the 400-year-old Shintō shrine Irugi Jinja and its Buddhist neighbor, the temple Kannonji (観音寺). Seamlessly blending religious belief and commerce, Irugi Jinja has a beautiful display of colorful traditional banners, each advertising a different kind of prayer you can pay for, from passing a school entrance exam or getting rid of a nagging illness to birthing a healthy child, being successful in business, or finding your soul mate.

The shrine offers many types of prayers and amulets, for a price. (© Gianni Simone)

I finally take refuge along the friendly banks of the Meguro River and walk downstream toward the point where the Yamanote bends sharply to the left and heads north. Curious walkers may want to check what lies beyond the condos crowding the riverfront. Like peeling off a layer of a city-sized onion, we find another hill. Here, in the middle of this megalopolis that never seems to sleep, this small secluded neighborhood is an improbable green paradise.

These streets are exceptionally quiet, and depending on your aural sensitivity, your ears will either pick up the rustling of the leaves or the buildings’ steady breathing: the long, drawn-out hum of the air conditioning and the dulled whirr of electrical gadgetry.

Trains and Famous Graves

My next goal is Iruki Bridge. From here, I get a nice view of the Shinkansen slowly approaching Shinagawa Station and the green Yamanote speeding off from it. If you are patient and lucky, you can see the two trains overlap.

This is a truly exciting spot for trainspotters who can admire different trains passing, including the blue convoys of the JR Keihin Tōhoku Line and the red ones of the Keikyū Line.

But that’s not all: A centuries-old cemetery belonging to Tōkaiji, a venerable Buddhist temple, lies wedged between multiple rail tracks as the trains keep rushing by one after another. Here the dead can only rest in peace at night. Also, this is arguably the only place where you can get so close to the Shinkansen trains “in the wild” (namely, outside a station) that you can almost touch them. A small path in the labyrinthine cemetery abruptly ends against the railway wall, and while you wonder what this all means, a bullet train blindsides you, awaking you from your reverie.

Tōkaiji’s centuries-old cemeteries lies wedged between the Shinkansen, the Yamanote, and the Keikyu lines. (© Gianni Simone)

Now walking northward along the First Keihin Road toward Shinagawa, I reach the massive flight of stairs leading to Shinagawa Jinja. At the back of the shrine’s sacred grounds is the grave of Itagaki Taisuke (1837–1919), a patriot from the Tosa clan in what is now Kōchi Prefecture who led the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement in the Meiji era (1868–1912). However, I’m more interested in the shopping street I spy across the wide avenue.

Traditional Districts Alongside Tokyo’s Newest

Having had my fill of ferroconcrete, the Kita-Banba area feels warmer and more intimate; an oasis of two- and three-story houses. Narrow side streets overgrown with wild plants; a tiny, colorful neighborhood temple; a shop selling zōri and geta (traditional footwear) that—the young female owner tells me—was built during Meiji; another one, a hardware store called Hoshino, old enough to have its name written from right to left, the way they used to do in the past; people stopping on their way home to chat with their neighbors.

One of the oldest stores along the Old Tōkaidō is a traditional footwear shop that opened during the Meiji era. (© Gianni Simone)

The hardware store Hoshino is so old that its name is written from right to left. (© Gianni Simone)

Shinagawa Station, not far north of Kita-Banba, takes pride of place in Tokyo’s history. After all, it was the starting point of the original Yamanote Line (40 years before the loop was completed) and the first victim of Godzilla’s rage when the monster visited Tokyo in the original 1954 film.

It’s hard to imagine that the station once directly faced the sea. In fact, the whole area east of the station is reclaimed land. For many years, the Kōnan and Shibaura districts located between Shinagawa and Takanawa Gateway stations were lonely places full of warehouses, factories, and facilities of the metropolitan government. However, since the turn of the century, developers have taken control of this expensive piece of land, building one tower condo after another and attracting many young families.

The Takahama canal flows past the new residential districts east of Shinagawa Station. (© Gianni Simone)

The wide Kōnan Ryokusui Park, bordered by the Tokyo Monorail, is full of running, jumping, and screaming kids. One wonders what they are doing here in this quasi no-man’s land that until 150 years ago was still open water. The area may have been developed and colonized (I count five high-rise condos around the park) but somehow it still feels alien and definitely artificial, like people are not supposed to be here.

Across the canal, a jumble of surviving gray warehouses, cranes, and fishing boats remind us that this is not a typical residence area and still retains the rough edges of an older, grittier version of Tokyo.

Development Around the Youngest Yamanote Stop

Takanawa Gateway, the newest jewel in the Yamanote crown (it opened in 2020), represents Tokyo’s future. The Kuma Kengo–designed station building is undoubtedly beautiful, but the surrounding area is still a work in progress. Even on Saturdays, hammering, drilling, sawing, and other harsh noises come from the gargantuan construction site next to the station.

Newly built Takanawa Gateway Station, by the architect Kuma Kengo. (© Gianni Simone)

One of the project’s victims is the obake (ghost) tunnel. This infamous spot is also known as the kubi-magari (neck-bending) tunnel because its ceiling is so low (170 centimeters) that taller people must bend to walk through it. Alas, they are currently digging a new road for cars, so the tunnel’s days are numbered.

The obake tunnel is only 170 centimeters high. (© Gianni Simone)

We end this walk in Shibaura, near Tamachi Station. This artificial island is yet another residential oasis of peace for the privileged and upwardly mobile. Giant slabs of inhabited concrete like the Grove Tower and Bloom Tower make me wonder what will happen to their residents when the next big earthquake comes, confronting them with the unenviable prospect of being stuck in their high-rise elevatorless homes, trekking up 20 to 30 stories worth of stairs with water and food.

Sitting on a bench facing one of the canals, I consider the situation while watching the slick monorail trains glide above the water.

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: The Tokyo Monorail glides over the bay near Tamachi Station. © Gianni Simone.)

Related Tags

train Tokyo Shinagawa walking Yamanote Line Ōsaki Takanawa Gateway Tamachi