A Love for Print and Paper: Used and Antiquarian Books in Japan

Jinbōchō Through the Years: The Story of Tokyo’s Secondhand Book District

Guide to Japan Culture Society History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Jinbōchō district in Chiyoda, Tokyo, is home to one of the world’s biggest congregations of secondhand bookstores. There are around 130 in total, specializing in everything from antiquarian works to manga. Sakota Ryōsuke, the owner of the Keyaki Shoten store, says the establishment of a number of universities in the wider Kanda area in the Meiji era (1868–1912) played a big part in encouraging the trend. “The forerunner to the University of Tokyo was founded in Kanda in 1877, and it was followed by others like Gakushūin University, the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Meiji University, and Senshū University. With the rapid increase in demand for textbooks, foreign books, and other specialist texts, more stores appeared selling foreign books secondhand, and this was the start of Jinbōchō as a center for books.”

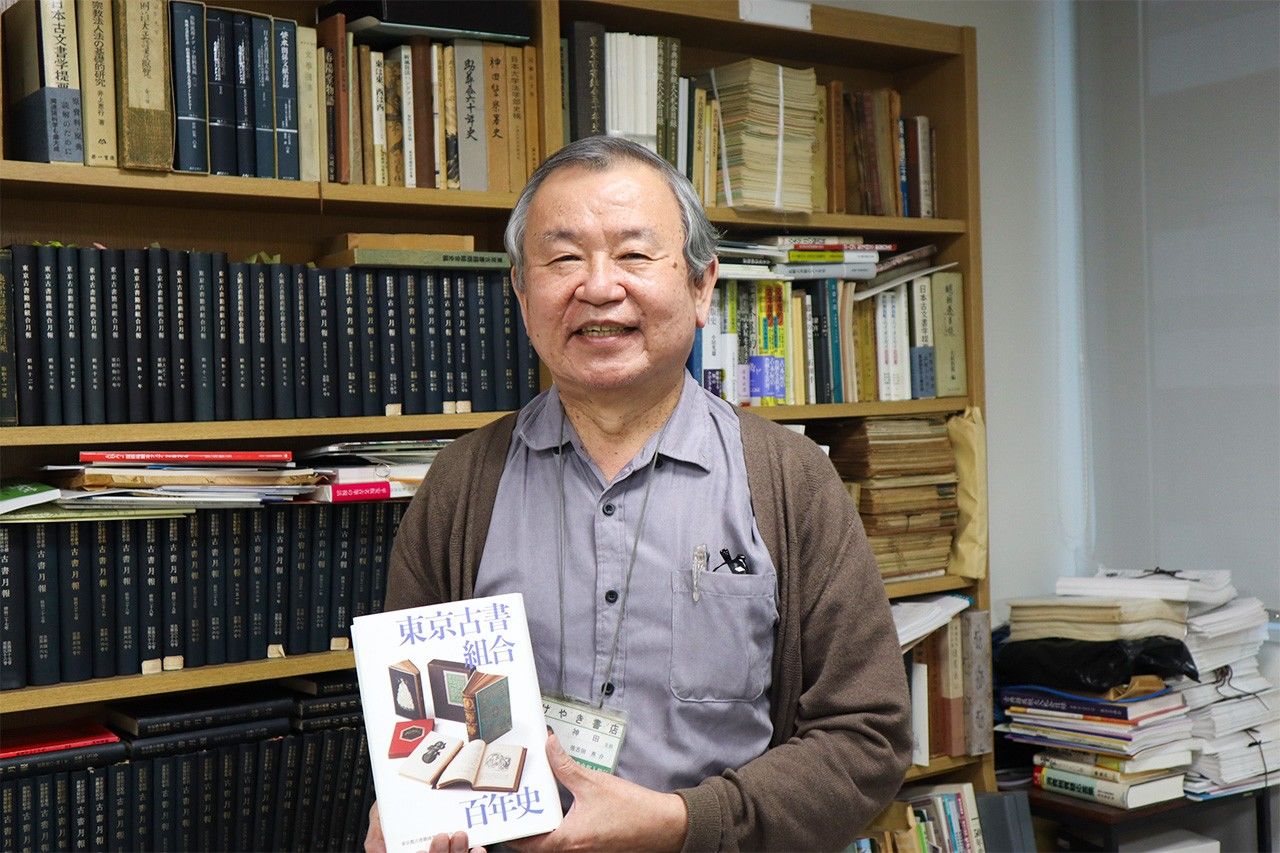

Sakota Ryōsuke at Tokyo Kosho Kaikan, the headquarters of a local association of booksellers. (© Nippon.com)

Sakota headed the editorial committee of a history of the area published in 2021 by the Tokyo Association of Dealers in Old Books. We spoke with him about his knowledge of and experiences in Jinbōchō.

Disasters and Growth

In the Edo period (1603–1868), bookstores sold both new and secondhand works and were also involved in publishing, but these became separate forms of business under the Meiji government, and a distribution network for new publications gradually established itself. By around 1887, most of the book businesses that had been around since the Edo period were no longer in operation.

“As there were many students and instructors who wanted to sell books they no longer needed, a new generation of secondhand bookstores started up,” Sakota says. “Yūhikaku, established in 1877, was the first secondhand store for foreign books, and four years later Sanseidō was established. Both ended up becoming involved in publishing.”

Today, Yūhikaku is known for publishing books on law and other academic topics. Sanseidō split its sales and publishing businesses in 1915, and is famous for publishing textbooks and dictionaries.

In 1889, the Tōkaidō Main Line fully opened. This rail connection between Shinbashi, Tokyo, and Kobe was a boon for the secondhand book trade, which had previously relied on steamship, and easier transportation helped distribution to expand between the main hubs of Kansai and Kantō and to points beyond.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, the main thoroughfare Yasukuni-dōri linked Chiyoda to Shinjuku in the west of Tokyo. After a 1913 fire caused major damage in Jinbōchō, the district transformed, as many used bookstores established premises along Yasukuni-dōri, including some that relocated.

The disaster was also a business opportunity for the industry. A number of universities and other educational institutions were completely destroyed and needed to resupply libraries as part of reconstruction. Bookstores were inundated with orders.

Iwanami Shoten opened after the fire in 1913. At first, it dealt mainly with secondhand books, but in the following year, it published Natsume Sōseki’s masterpiece Kokoro. This was apparently published at the author’s own expense, with Sōseki also responsible for the binding. With this as its springboard, Iwanami grew to become a major publisher.

The Great Kantō Earthquake devastated Tokyo in 1923, but also contributed to the growth of the secondhand book business. While stores selling new books, distributors, printing companies, and paper factories took time to find their feet afterward, secondhand book stock was in storage nationwide, and could be supplied from Osaka and elsewhere. As after the fire a decade earlier, educational institutions needed to reestablish their book collections, bringing a spike in the demand for secondhand books.

Trade Association and Postwar Boom

In the 1890s, several markets were set up in Tokyo for dealers to procure secondhand inventory. “Around this time, there was a surge in the circulation of foreign books, and a number of private markets were created around the Jinbōchō area,” Sakota explains. “Gradually momentum built for establishing a trade association for all the secondhand bookstores.”

After many twists and turns, the forerunner to today’s Tokyo Association of Dealers in Old Books was established in 1920, which came to hold markets almost every day for its members to exchange books. The transactions in these markets helped to decide book prices.

“The controlled economy during World War II was the hardest time for the association,” says Sakota. “With the adoption of fixed prices, it was no longer possible to freely choose how much to pay, whether between dealers or when selling to customers, which made trading difficult. Store owners and staff members were conscripted for the war effort, and many stores went out of business.”

As Japan’s defeat loomed, Tokyo suffered extensive firebombing, but Jinbōchō miraculously escaped damage and so was able to recover quickly.

The immediate postwar era was a time of economic upheaval due to a freeze on bank deposits and a required switch to new yen banknotes; some people tried to acquire the new notes by selling antiques and antiquarian books. Notably, aristocrats who lost their status and other wealthy people whose income plummeted under the democratizing reforms of the US Occupation flooded the market with treasured rare tomes and classic works. Meanwhile, educational reforms led to the establishment of almost 200 new universities by 1949, which brought major demand for secondhand books.

Saved by Online Sales

Sakota says that the specialization by store that exists today started around the end of Japan’s high-growth period in the early 1970s. “In an area where there are more than a hundred stores all in the same business, survival is impossible without specialization. I think that secondhand bookstores are a niche industry, and their strength lies in dealing with products unavailable elsewhere.”

Until Japan’s bubble economy collapsed in the early 1990s, the publishing industry, including secondhand book businesses, enjoyed soaring growth. However, Sakota says, “From the 1990s onward, the arrival of the internet saw the emergence of Amazon and other online stores, which led to a rapid decline in proceeds among traditional stores. Those selling new books were hit hardest.”

The major used goods chain BookOff was founded in 1990 and expanded across the whole of Japan, but Sakota dismisses it as lacking substance. “As well as secondhand books, it deals in other goods, and there’s no specialist book knowledge anyway. We carefully appraise individual works and decide their price. There are association members who find undervalued books at BookOff outlets and sell them for a high price in their own stores.”

Apart from the war, notes Sakota, the industry’s biggest crisis came with the widespread adoption of the internet. “There was a sense of crisis that if something wasn’t done, we wouldn’t find successors, and business would just dwindle away. This led to the launch of the website Nihon no Furuhon-ya [Japan’s Secondhand Bookstores] in 1996. With the participation of many stores, it has smoothly remained in operation.”

The Nihon no Furuhon-ya website. This snapshot includes featured books on surrealism, marking 100 years since the birth of Abe Kōbō, and on Manchukuo, marking 90 years since the establishment of Japan’s puppet state in Manchuria.

Sakota goes on: “During the COVID-19 pandemic, we couldn’t have stayed afloat without online sales. Secondhand bookstores were defined by the government as ‘nonessential and non-urgent,’ and received requests to close. But while Jinbōchō stores were shuttered, orders via the website increased.”

Book Markets

There are three Kosho Kaikan halls in the metropolis—Tokyo, Seibu, and Nanbu—where association members can trade books. At the Tokyo Kosho Kaikan, near Jinbōchō, there are all kinds of events for dealing in Japanese or foreign books, including those focusing on subcultures like manga.

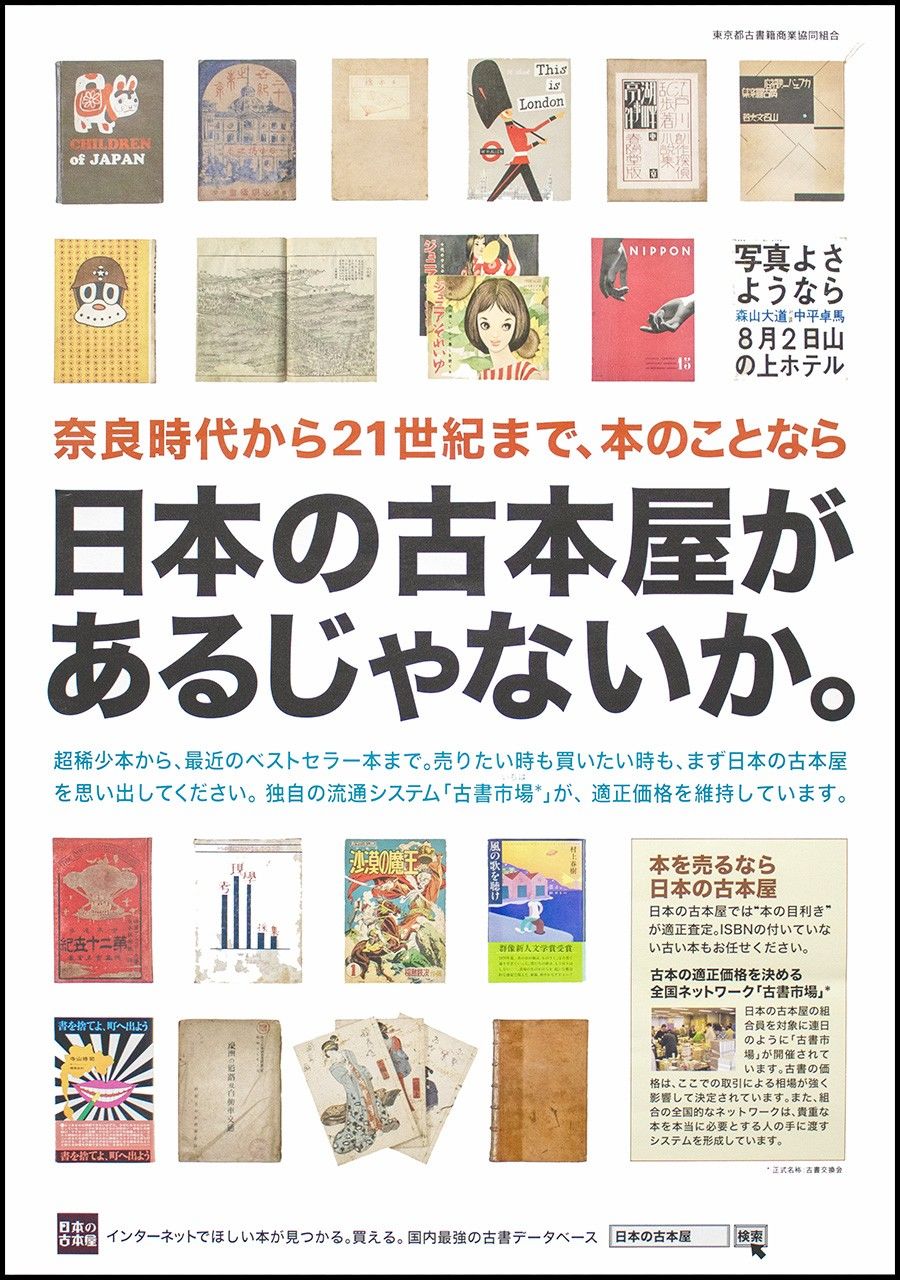

A Tokyo Association of Dealers in Old Books poster promoting Japan’s secondhand bookstores.

“There’s also a market aimed at the general public held on Friday and Saturday almost every week,” Sakota says. “Regular customers line up outside the venue an hour before it starts.”

Every year, major markets are held in Jinbōchō in spring and autumn. The streets are busiest during the Kanda Secondhand Book Festival from October to November. A million books or so are laid out on stalls along the sidewalks of Yasukuni-dōri.

The Appeal of Old Books

After graduating from high school, Sakota worked at the long-standing store Isseidō Booksellers, but in 1987 he set up his own shop, Keyaki Shoten, specializing in modern literature.

“I like the Buraiha [Decadent School] writers, so at first I mainly collected authors like Dazai Osamu, Sakaguchi Ango, and Oda Sakunosuke,” he says. “Now I take orders online too, but I still value catalogue sales, which I studied at Isseidō.”

Book catalogues are sent to collectors, universities, and others with information on authors, publishers, price, and content, as well as sometimes photographs. This sales method has been around for more than a century, and as stores that rely on online business increase, only a minority now produce catalogues. Even so, Sakota has no intention of giving up this practice—despite the time and money it takes—saying that there are customers who eagerly ask to see his next quarterly catalogue. “I couldn’t do it if I didn’t love books,” he says.

But what are the enjoyable aspects about running a secondhand bookstore? “There are always new discoveries. For example, maybe one first edition might for some reason have different colored endpapers to the others. I imagine in this case that probably a paper shortage led to the hurried use of a different kind. Sometimes these kinds of irregular books are valued highly.

“Anyway, there’s the fun of never knowing what you’ll happen on next. Once I obtained a signed Dazai book that he sent straight to his sister, but the one that really excited me was a handwritten manuscript of Ango’s “Hakuchi” [trans. by George Saito as “The Idiot”]. But even if I might burn to get hold of something, I’m not so attached as to resist selling it on. I always find a buyer.

“When secondhand book dealers are competing at a market, a book might be sold for millions or tens of millions of yen, but highly rare and valuable books almost never appear in catalogues or at markets. If a collector passes away, or for some reason books go on sale, they go to another collector via a bookseller with whom they were on good terms. If you want to make big deals, you have to secure good customers.”

Facing the Future

Regarding the future of the industry, Sakota says, “There are stores going out of business, but there are also young people starting out, so so we aren’t seeing a rapid slump for used-book stores like that seen for stores selling new books.”

“You used to need an actual store to get a permit to deal in secondhand goods, but now it’s possible to do business online alone, which makes it easy for young people to get started. The association holds occasional seminars on opening secondhand bookstores, which are always packed. You need specialist knowledge on secondhand books, but now it’s possible to pick that up online as well, so if the motivation’s there, you can gradually learn what you need to know.”

Recent years have seen new kinds of ventures, such as combinations with cafés and shared stores where individuals and groups can rent shelves to sell books. Sakota is in favor. “I think it’s fine if people pick the approaches that suit them. There’s nothing wrong with changing with the times. Without change, the secondhand book industry has no future.”

(Originally written by Kimie Itakur of Nippon.com and published in Japanese on May 7, 2024. Banner photo: Jinbōchō in October 2022, as the Kanda Secondhand Book Festival is held for the first time in three years after the COVID-19 pandemic. © Jiji.)