Addressing Social Issues Where Art and Welfare Meet

Start-Up Heralbony Working for Artists with Intellectual Disabilities

Arts Culture Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Finding the Value in Difference

Heralbony’s founders, twin brothers Fumito and Takaya, have another brother, Shōta, four years their senior. Shōta has a severe autism spectrum disorder, and his brothers grew up conscious that people around Shōta “felt sorry” for him due to this intellectual disability. The twins were determined to transform that attitude in society.

They were inspired by a visit to Runbinī, a gallery featuring a “borderless art collection” in Hanamaki, Iwate Prefecture. Many of the works on display there, created by people with disabilities, featured intricate lines and bright colors, and all of them made a deep impression. The Matsudas felt this art should be enjoyed by more people and wanted to create a mechanism by which the artists would be suitably remunerated.

One of the “art rooms” at the Hotel Mazarium in Morioka, Iwate. Eight of the hotel’s 38 guest rooms are decorated with designs by Heralbony artists. The artists receive ¥500 for each night of a guest’s stay. (© Miwa Noriaki)

In Japan, the prevailing assumption is that people with disabilities live through handouts and aid. Therefore, even if they produce incredible works of art, they escape wider notice.

Vocational centers for people with disabilities tend to focus on support rather than on the work they give people. Consequently, the average wage at centers for people with severe disabilities was just ¥16,507 per month in 2021, according to Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare data. This is nowhere near a living wage.

The well-known Japanese avant-garde artist Kusama Yayoi has suffered visual and auditory hallucinations for most of her life due to schizophrenia, but nobody refers to her as a “disabled artist.” Kusama’s world needs no labeling about illness or disability to explain it.

According to Heralbony, “The term ‘disabilities’ can refer to a multitude of unique qualities.” Similarly, artworks by artists with intellectual disabilities range from subtle to bold. ”

Fumito explains: “We hope to drive a change in society’s image of the works of artists with disabilities, and we therefore promote their art as objects of value. If we can repudiate the prevailing perception by presenting ‘extraordinary arts’ as indispensable, I believe it will be a tremendous innovation.”

Matsuda Fumito. (© Miwa Noriaki)

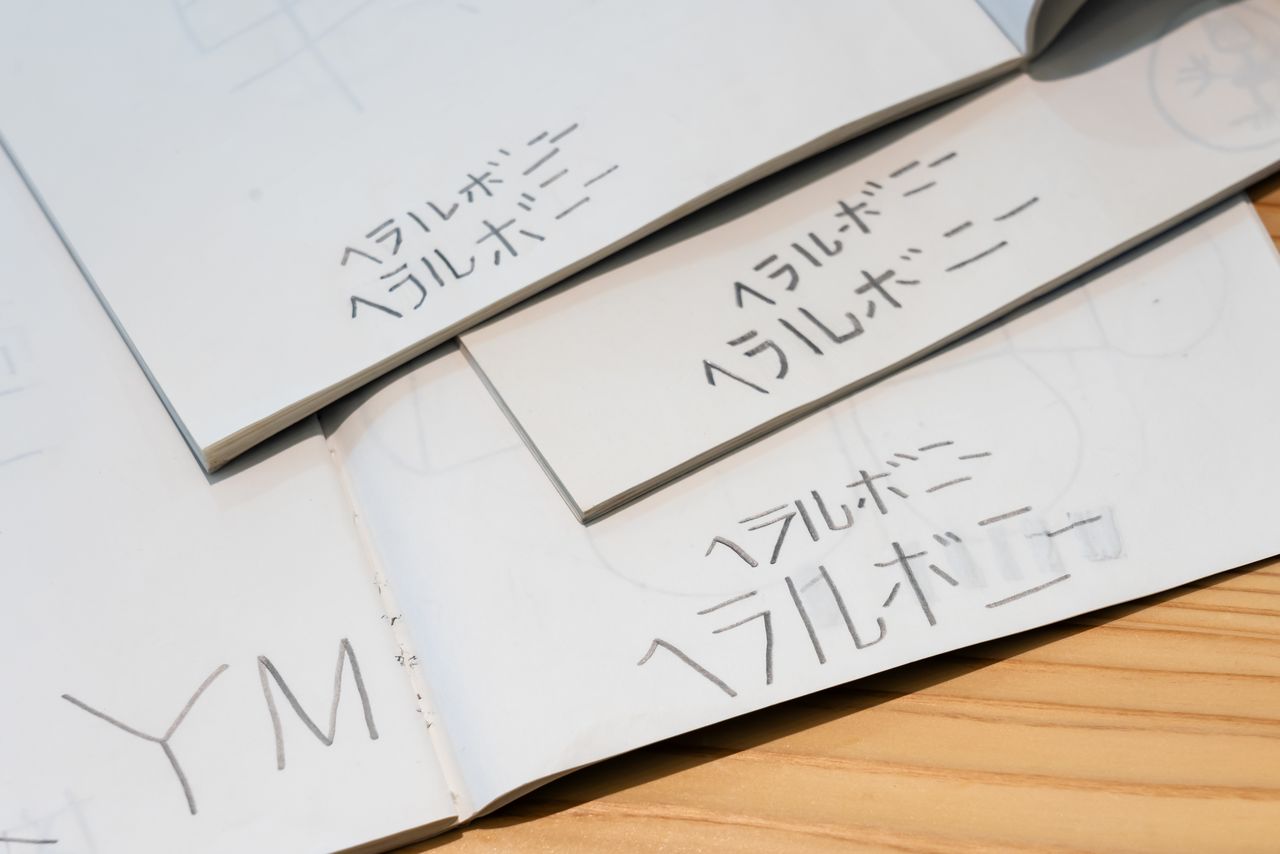

The company name comes from a random word that their brother Shōta wrote in his notebook as a child. (© Miwa Noriaki)

Fashion that Ties Creators to Wider Society

Fumito and Takaya came up with the idea of producing goods featuring art-inspired designs to share the impact and wonder they felt at Runbinī with more people. Their first endeavor was to produce neckties, as a symbol of tying people with disabilities into wider society.

But finding a company to manufacture high-quality neckties was harder than expected. After numerous rejections, they approached the well-known necktie retailer Ginza Taya, which empathized with the twins’ enthusiasm and agreed to produce the ties. “Because we wanted to change the image of disability as deficiency, we were pleased to start out with a luxury product.”

Heralbony art neckties. The high quality of needlework and weaving technology is obvious. (© Miwa Noriaki)

After this, Heralbony expanded its collaborations with other companies. For example, art works from Heralbony were used by Japan Airlines for its in-flight box meal sleeves, on Yonex snowboards, and to decorate the Tōkaidō Shinkansen ticket office and station ramps at Tokyo Station.

At one time, the company’s products were in a department store window display alongside luxury brands including Hermès and Louis Vuitton. Today, Heralbony’s artists’ works appear on over 100 products and packages each year, for everything from furniture and clothing to foods.

Art by Kudō Midori, contracted with Heralbony, was used for a bus wrap. (© Miwa Noriaki)

Collaborations that Boost Awareness

In the art world, the standard practice is to stage exhibitions and sell works to make a profit. But Heralbony’s business focuses on creating opportunities for more people to see the art, increasing the creators’ earnings through licensing.

Heralbony’s shop in a Morioka department store (currently closed for refurbishment and set to reopen in December 2024). (© Miwa Noriaki)

Fumito explains their business approach: “Our aim is to build mechanisms whereby Heralbony can gain exposure for the art, enhance the brand’s value, and derive an ongoing profit.”

Currently, Heralbony has licensed over 2,000 works by 153 artists from 37 welfare facilities in Japan and elsewhere. Partner companies pay Heralbony to use the art in their designs, helping to remunerate the artists and facilities.

Another “art room” at Morioka’s Hotel Mazarium. (© Miwa Noriaki)

Expanding an Idea, Not the Market

According to Fumito, “Heralbony aims to create a new alternative in the field of disabled welfare. We hope to spread the idea of a society that is affirming of people even if they have a disability.” He emphasizes: “We want to create the ground for a new market based on the realization of this idea.”

“When members of society have no contact with people with disabilities, it fosters discrimination and prejudice. If they encounter these people in circumstances that engender respect, though, it’s sure to change their perceptions.”

Heralbony artist Kinugasa Taisuke painted at an event held in a Kyoto department store. People were astonished at the speed at which he worked. (Courtesy Heralbony)

When Caregivers Die

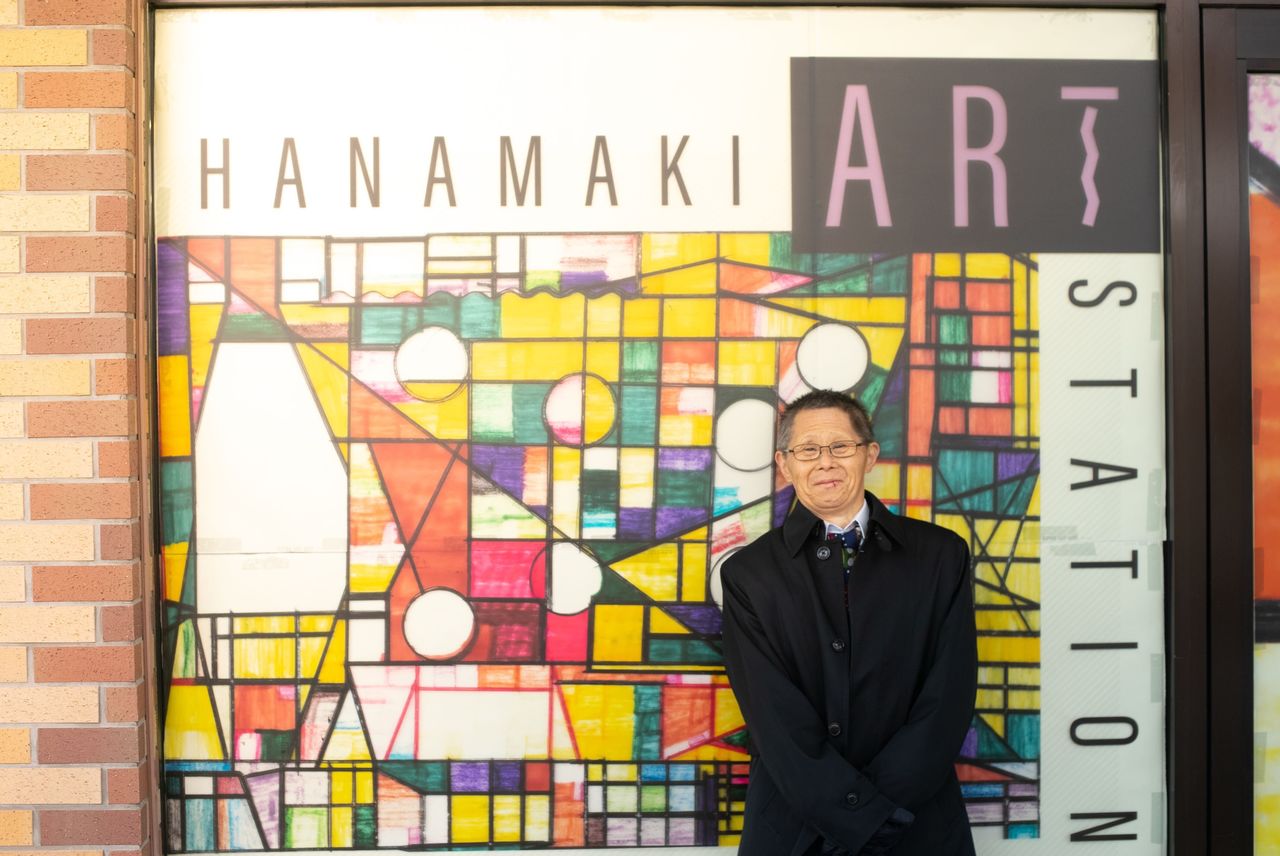

In December 2019, when art by Heralbony artist Yaegashi Kiyoshi, who had Down syndrome, was used in stained glass-like designs on 164 windows of JR Hanamaki Station, the local newspaper referred to him as “the artist” rather than “a disabled person.” For Fumito, this symbolized the impact of their work.

Another time, the family of one artist informed him that they would be lodging a tax return on their artist child’s behalf, because they had earned ¥4 million that year from licensing and other income flows. In a letter of thanks, they said: “The seemingly comical idea that we might be supported by our child could become a reality.”

Fumito explains that many parents of children with intellectual disabilities worry whether their child will struggle financially after they die. It must be reassuring for them if the child can find a way to earn a living outside of the welfare support framework.

The late Yaegashi Kiyoshi in front of his artwork, used to wrap JR Hanamaki Station. (Courtesy Heralbony)

The World Stage

In 2024, Heralbony received the prize for Employee Experience, Diversity, and Inclusion in the 2024 LVMH Innovation Award, staged by Louis Vuitton’s parent company LVMH to recognize the achievements of start-up companies. It was the first time a Japanese company had received the award. As a result, Heralbony will receive business support from LVMH, whereby it will launch its full-scale business overseas. The company’s first overseas branch will open in Paris in July 2024.

In 2024, it also established the Heralbony Art Prize for artists with disabilities around the world (entries have closed for this year).

Heralbony art team member Tamaki Honoka (right) shares her hope that the Heralbony Art Prize can provide a gateway to success for artists. (© Miwa Noriaki)

Judges include Christian Berst, founder of a leading art brut gallery in Paris, and Hibino Katsuhiko, president of the Tokyo University of the Arts. An exhibition of the best works will be held in Tokyo.

Berst expresses his support, stating: “Through licensing art, rather than just selling it, Heralbony has developed a business that can popularize the works. Its business is not profit-driven, but sincerely seeks to work with the artists. I hope it can bring a breath of fresh air to Paris.”

With its roots in a loving family, Heralbony is seeing to create a new culture. By helping people to experience the talent of its artists, it aims to change the perception of those who “feel sorry” for those with disabilities. Fumito’s passion makes it easier to believe that such change is not far off.

(Banner photo: The artwork Untitled, by Sasaki Sanae, adorning curtains, upholstery, and Fumito’s necktie. She has been with Heralbony since its early days. © Miwa Noriaki.)