“Kagami Mochi”: Japan’s New Year Rice Cakes

Lifestyle Culture Food and Drink- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

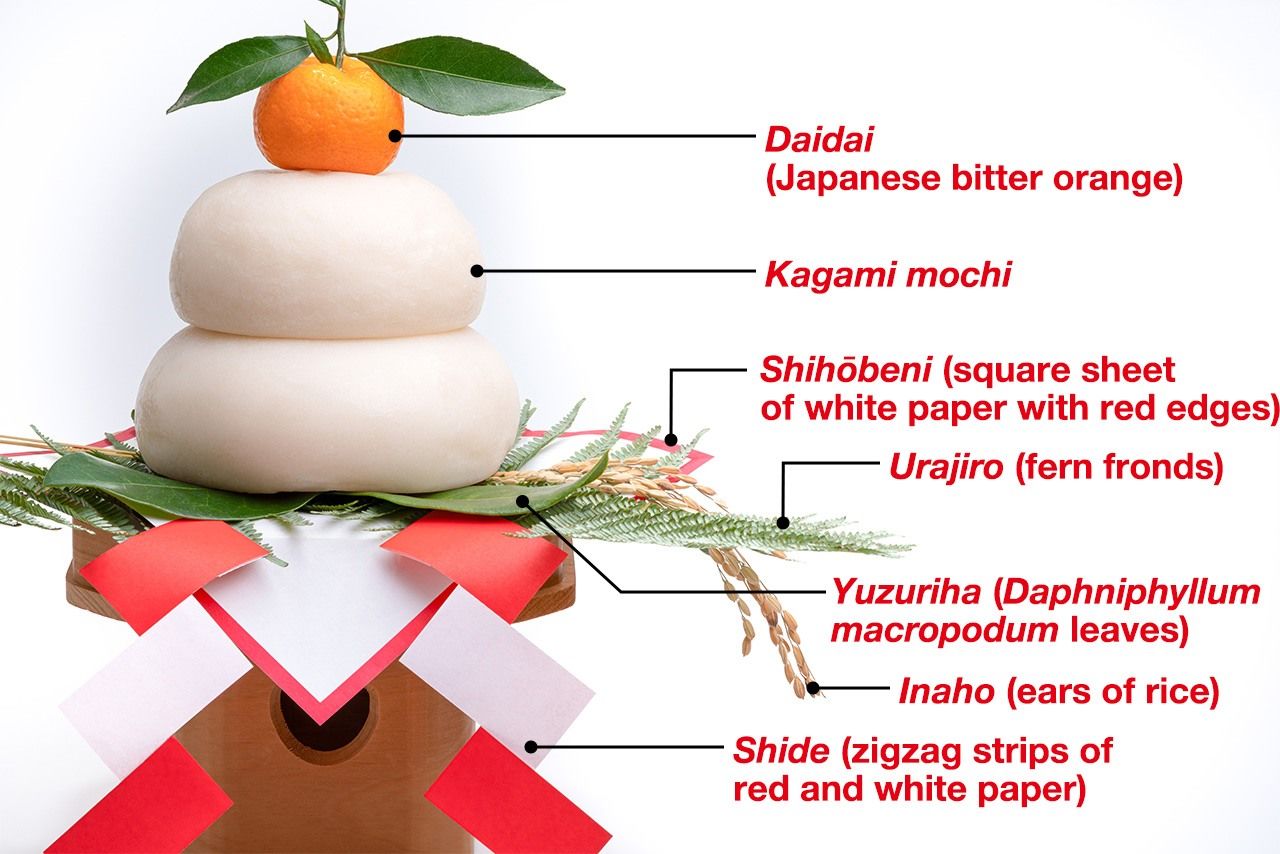

Two mochi rice cakes, stacked one on top of the other, make up a key decoration for Japanese New Year: the kagami mochi. The various parts of the decoration have different auspicious meanings, as detailed below.

A Traditional Kagami Mochi Decoration

Kagami Mochi

This is mochi, or rice cake, formed into a round shape to represent a mirror (kagami), one of the three sacred treasures, and displayed at New Year as an offering to the New Year gods (toshigami). Two cakes are stacked together, said to symbolize yin (the moon) and yang (the sun).

Daidai

While an easily available mandarin orange is now usually placed on top of the kagami mochi, traditionally it was a daidai, or Japanese bitter orange. Daidai is a homophone for “through the generations,” so it is thought to express the wish for prosperity of future generations.

As it has a thick peel and a lot of seeds, it is generally inedible, but the juice has a refreshing sourness and is used as an ingredient in ponzu and other condiments.

Urajiro

This is a large evergreen type of shida or fern. Its Japanese name urajiro (literally, “white underside”) comes from it being dark green on its surface and white underneath. Due to the fronds growing in pairs, plus the plant being highly fertile and growing in clusters, it is said to symbolize marital harmony and fertility.

Yuzuriha

This plant, known commonly as False Daphne, puts out new leaves before the older ones fall, so it is regarded as a symbol of continuance of the family line.

Shide

These are strips of paper cut in the shape of lightning bolts. They ward off evil spirits and create purified spaces.

Shihōbeni

This is a square sheet of white washi paper with red edges. It represents offerings to heaven, earth and all four directions to ward off misfortune and to pray for prosperity throughout the year.

When to Display and Eat Kagami Mochi

Fortunate Timing

Recently, many people buy kagami mochi at supermarkets and depachika, the underground level of department stores. In the past though, the rice cakes were made by pounding rice by hand at the end of the year. In Japanese, the number nine, ku, has the same pronunciation as for the word “suffering.” Mochi that was pounded on the ninth, nineteenth, or twenty-ninth of the month was known as kunchi-mochi (literally, “ninth-day mochi) and disliked because of that association with suffering. As an extension of this, there are still many people who avoid putting kagami mochi out on display on December 29. Some though have a more positive attitude towards that date as 29 can be read as fuku, meaning “luck.”

December 31 is also regarded as a day when kagami mochi and shimenawa decorations should not be put out, due to the view it is not good to be rushing the day before welcoming the New Year gods into one’s home.

While avoiding these two days, typically it is considered acceptable to start displaying the kagami mochi any time from December 13, although many households begin after Christmas, with December 28 considered particularly auspicious, as the number eight is thought to be lucky.

Kagami mochi that has dried and cracked. (© Pixta)

Kagami Biraki (January 11)

The belief is that the mochi offered to the deities contains their power. Taking the kagami mochi down from display to eat is a way of praying to receive that power and to enjoy good health. This is a tradition known as kagami-biraki (opening the mirror). Words like “break” (waru) and “cut” (kiru), which are associated with the death of samurai, are not used. The mochi, which is now hard, is hit with a wooden mallet or similar utensil to form bite-sized pieces, which can then be eaten, such as in zōni soup or deep fried to make agemochi.

(Translated from Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)