Demon Slayer: A Cultural Phenomenon for Pandemic Times

Culture Society Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

2020, the year of COVID-19, closed with the surprising news that, as of December 28, Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train had earned ¥32.48 billion at the domestic box office, taking it past Studio Ghibli’s Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi (Spirited Away) to become the highest grossing domestic film in Japan’s history. The final book volume of the manga series, Kimetsu no yaiba, was published on December 4, at which point the series as a whole had over 120 million copies in circulation. On the final volume’s release day, many bookstores in major cities reported customers lining up outside to get their copy.

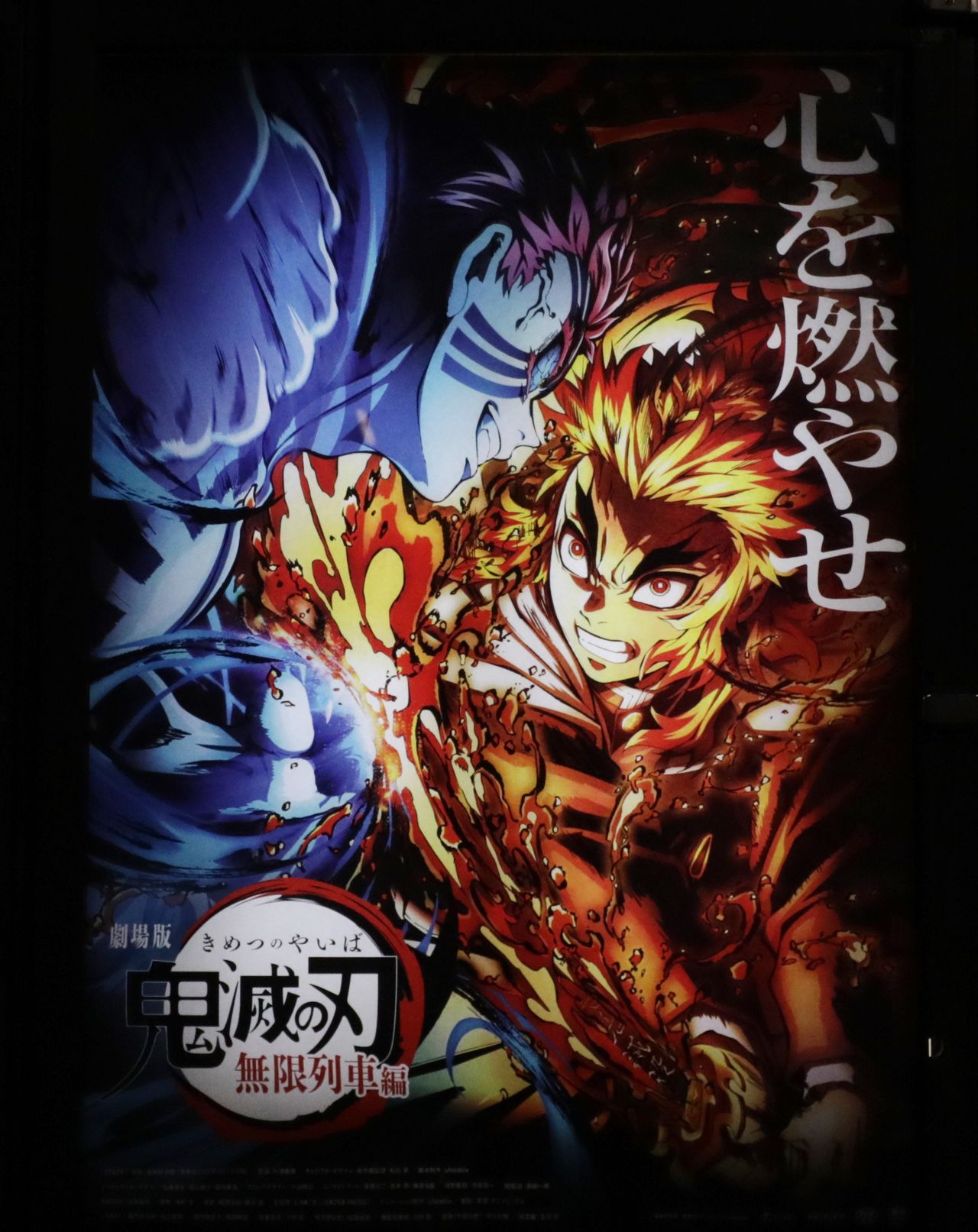

A poster for the anime Demon Slayer the Movie: Mugen Train, which became the highest-grossing film of all time at the Japanese box office, in Naka Ward, Yokohama City, on December 28, 2020. (© Jiji)

The Demon Slayer cultural phenomenon was completely unexpected. When the television anime first aired in April 2019, the title had already been enormously popular with the core audience of manga fans. The final chapter of the series was published in Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine on May 18, and social media was quickly set ablaze with discussions of the way it ended, particularly as it was at the height of its popularity. Rumors about the series began to spread like urban legends, including the actual revelation that the author, Gotōge Koyoharu, is a woman.

Not long after the October 2020 premier of the movie, though, I started to notice discussion of it in more mainstream media, indicating that its popularity had become far more widespread. For someone inside the manga media landscape, it was a shock, as if a toy balloon I held in my hands suddenly grew into a huge airship and took flight.

Digging Up the Secrets of a Megahit

What is it about Demon Slayer that made this popularity possible?

It is rare for a manga to become a cultural phenomenon on its own, since in most cases it is the result of transmedia distribution, especially via television anime adaptation. In general, the Demon Slayer phenomenon is a perfect example of a transmedia franchise development, with the original manga being adapted into a television anime, and then progressing to the cinema, and so growing into its own brand. This development of manga into television anime and then on to the cinema is a standard pattern, and is not at all particular to Demon Slayer, though.

So, can the secret to this megahit status be found in the content—the story, characters, or worldview?

Demon Slayer is an adventure story aimed at a young, male audience, and is generally a story of growth and maturation. To summarize, the main character is a boy named Kamado Tanjirō. He loses most of his family in a demon attack, except his younger sister, Nezuko, who herself is turned into a demon. He then joins a team, the Demon Slayer Corps, to carry on fighting the enemy. Tanjirō is a typical fighting manga protagonist, who depends on his own innate potential rather than any natural gifts to break through obstacles. He is gifted with a very keen sense of smell, which allows him to detect even the emotions and movements of others, although this gift is not particularly useful in battle.

The story pits two extremes, the forces of justice and those of evil, against each other in direct conflict. The former is represented by the Demon Slayer Corps, whose goal is to eliminate the diabolical creatures. The latter is the Twelve Kizuki, a group of humans transformed into demons and then organized into a group by the demon lord Kibutsuji Muzan. It follows the common tropes of fighting manga for boys, with the growth of a trusting relationship with senior members, friendships between comrades, and the younger sister who can make up for the main character’s deficiencies, in this case because her demonic transformation gives her great power.

As a result, the characters, worldview, and storytelling are all relatively straightforward and easy to understand. In other words, it is perfectly geared for commercial success. Naturally, Demon Slayer displays some unique flavor, but every work has its own unique flair. In comparing it to other popular franchises, I cannot see any particularly unusual elements that make it stand out.

Then, going back to our question, what is it that has made it such a phenomenal hit? I believe the answer can be found in the strategy used to maintain sales after the series’ end, and a special empathy found in a general audience whose values have been forced to change in the pandemic. So, let us examine those two facets.

A Choice of Structure

When we look at the story structure of fighting manga, there are two basic patterns: the escalating, episodic “level-clearing” structure, and the “back-calculation” story structure, with a certain end goal in mind and story elements assembled to move the protagonist toward it. The “level-clearing” structure features protagonists who proceed through one battle or challenge after another, growing stronger and defeating ever more powerful opponents in a story that has no ostensible end, as exemplified by titles like One Piece and Dragon Ball. The “back-calculation” story, however, uses the payoff of elaborately structured and foreshadowed events as it builds toward its fixed end in a limited serialization, like Assassination Classroom or Fullmetal Alchemist. Demon Slayer is one of the latter, and even with 23 books in the series it ranks as rather short in the adventure/fighting manga genre.

There has been a lot of attention on the fact that the manga Demon Slayer ended at the height of its popularity, but it is standard for manga of this type to end their runs in around 25 volumes. Rather than intentionally ending at the peak of its popularity, it seems likely the plan was actually to drive the popularity even higher after its end. Drawing out the serialization would certainly lead to more books being sold overall. But pushing a story of this type onward with ever-intensifying battles dilutes the catharsis of foreshadowed payoff, and thus reduces the appeal. It would be fatal to the story. Without the strategy of prolonging the story to sell more books, then, publishers must rely on keeping popularity going after the story ends to maintain book sales. How did they do that?

The Shared Sorrow of Ending

There were several years between the first appearance of the manga, in the February 16, 2016 issue of Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine, and its big break at the first season of the television anime running from April through September 2019. This meant there was significant lag in the story, as shown by the sixteenth volume of the manga, which was released in July while the first season was still airing.

In that volume, the head of the Ubuyashiki family and chief of the Demon Slayer Corps blows up his own house, sacrificing himself along with his wife and daughter, in order to spring a trap for the demon lord Kibutsuji Muzan. The event marked a clear and sudden start to the story’s final countdown. Fans who started out watching the anime and then decided to binge-read the published books got to the sixteenth volume and were obviously shocked that the story seemed to be over already, and many people turned to social media to share that shock. It was in October 2019, after this event and the shared experience of it via social media, that the Demon Slayer sellout phenomenon began with the release of volume 17. Incidentally, this volume features one of the main characters dying in battle with a demon. As beloved characters were lost and the story began to approach its end, readers began gathering on social media and elsewhere to take part in the final countdown together.

The magazine serialization ended in May 2020, but the book publishing schedule lagged far behind. The twehtieth volume of the book was published on May 13, just five days before the magazine serialization ended. The next to last volume, number 22, went on sale October 2, and the film was released just two weeks later. The twenty-third and final volume was not released until December 3, so that countdown went on and on for those who were following the series in books rather than in the magazine. That left right around two months for fans to enjoy the shared sorrow of the inevitable ending, as well as increasing their anticipation.

So, what if the series had gone on longer? Would fans have been as passionate if the story had been diluted by keeping it going to capitalize on the anime’s popularity? The results seem to argue against it. The strategy of allowing readers to publicly share the drawn-out ending drew new readers to join in the countdown, thus successfully increasing sales, and the story’s short life-span itself became part of the branding.

The Lingering Departed and Those who Carry On After

Thus, the series’s creators made strategic use of the ending to drive popularity and maintain sales. But Demon Slayer is undeniably a gruesome story. People are attacked and mercilessly slaughtered by unreasoning demons, and members of the Demon Slayer Corps fall one after another. What in such a story could possibly inspire empathy?

There are times throughout the story when the protagonist and other characters seem ready to give up on life, and then the spirits of family and friends lost to the demons return, descending into the unconscious to inspire. In other words, the departed linger on, remaining by our sides to help us even after death. The idea of the dead staying nearby is a core element of the story’s themes of connection and inheritance. Indeed, I believe the story argues that as long as someone remains to carry on our memories and ideals, our life can never truly end. It is a chance at eternity. That also means that while there is someone to carry on our ideals, self-sacrifice is in fact an act of devotion—to a cause, or to those around us. The devotion of that sacrifice can then inspire further devotion in those who remain and inherit our ideals, and we can take the story’s use of the lingering dead as a symbol of that inheritance of devotion.

The lingering dead also come to those who bear the sad fate of becoming demons. Demons to whom the lingering dead return have their memories and humanity restored before they die, and so offer the reader a glimpse of salvation, showing that even the worst of fates—to have reason torn away and be twisted into a demon—is not without hope.

The key sentiment in this story is only this: to protect those we care for. Everyone shares that sentiment, and even as it drives the characters inside the story, it helps keep readers emotionally involved. I believe it is this kind of shared sentiment, the empathy it created, is what led to Demon Slayer becoming so popular even with those who do not normally consume manga or anime.

There is a memorable line from Kibutsuji Muzan to the main character, Kamado Tanjirō. “Just think of being killed by me in the same way as dying in a natural disaster.” Reading a line like that evokes a certain reaction in readers. We have all witnessed major earthquakes. We have seen floods and typhoons in summer, and houses collapse under snow in winter, and of course we have lived day in and day out with the COVID-19 pandemic. We have all begun to see just how weak human beings are, and as we live lives of endless self-restraint in the pandemic, our values have begun to change.

Being forced away from the crowds of the city has made many of us feel lonely and surprised to realize that participating in all those events and activities had been an important part of what we assumed was a “fulfilling life.” I imagine everyone has had to take stock of what is truly important in life. Where do we find emotional fulfillment, with no end in sight for all of this? Perhaps the answer is what we seek in our sympathies with Tanjirō and his friends as they fight demons, symbols of unreason incarnate.

We have lost so many of the things that guided us through life, and must now build new values in a new normal. That may be the perfect time for a story featuring both horror and devotion.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: All 23 volumes of Gotōge Koyoharu’s popular manga Demon Slayer. © Jiji.)