Japan’s Water Utilities Threatened by a Declining Population

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Universal Access to Piped Water

Japan’s first modern high-pressure piped water system was completed in 1887 in Yokohama. At that time, many cities, particularly port cities, were plagued by water-borne infectious diseases. The congestion of wooden buildings in urban areas also meant that fires were quick to spread one they broke out, with devastating consequences. In an effort to secure public hygiene and prevent fires, the Japanese government set about building water supply systems throughout the country that would be operated and maintained by the municipal authorities.

There was a surge in the spread of piped water systems from the late 1950s into the 1980s during Japan’s era of rapid economic growth. As shown in Figure 1, the tap water supply rate of 26.9% in 1950 had gone up to more than 90% by 1980, and in 2016 was 97.6%.

Japan’s Tap Water: Tasty and Cheap

As Japan’s economic development progressed, industrial effluents and pollutants increased, causing numerous environmental problems. Water quality at the source deteriorated to such an extent that tap water took on a foul odor. The problem became so prevalent that the Ministry of Health and Welfare (now the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare) was compelled to act. Under a slogan calling for “delicious water supply,” the ministry implemented advanced water treatment technology which eventually solved the problem. Today, Japan’s tap water is not only of the highest quality, it is also provided for very low fees compared to other countries. Figure 2 shows the average water rates charged to households in a number of the world’s major cities. As you can see, Japanese water rates are significantly low.

A Crisis Situation

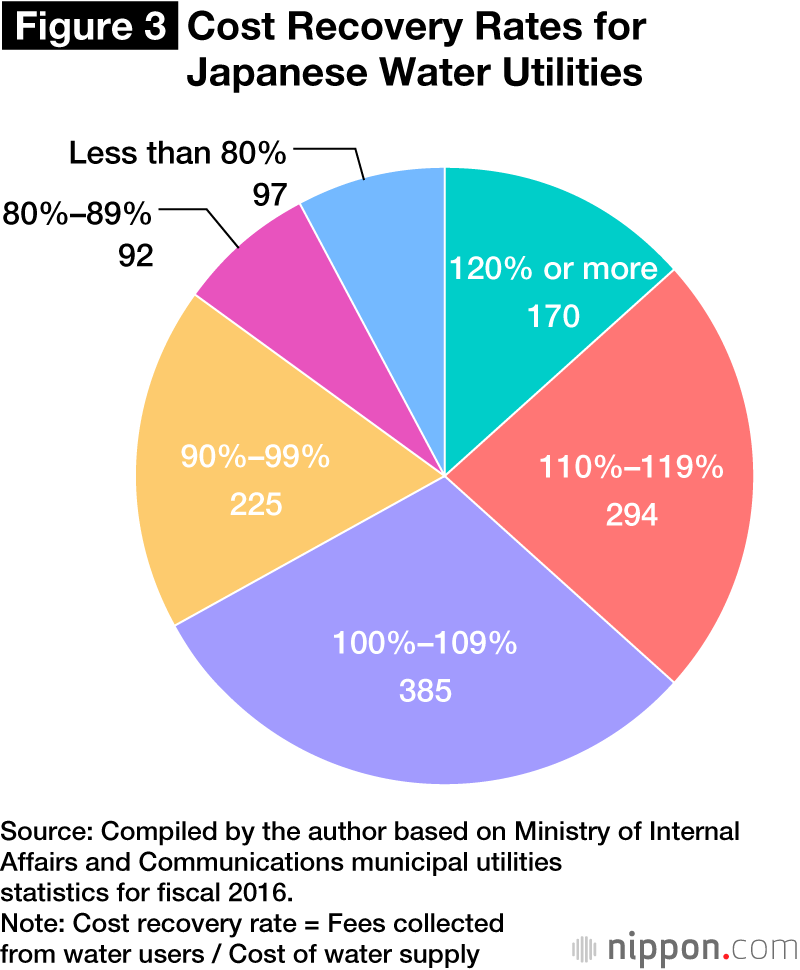

Japan’s water utility companies were able to supply the needs of a burgeoning economy and growing population with clean water meeting the most stringent standards in the world, but upon entering the twenty-first century, their job has become increasingly difficult. Figure 3 shows the fiscal 2016 cost recovery rates of Japanese water utilities providing tap water. As you can see, the rate is less than 100% for around a third (414) of the companies.

According to a March 2018 report predicting future water rates, compiled by Ernst and Young Shinnihon LLC and the Secretariat of the Water Security Council of Japan, roughly 90% of Japan’s water utility companies well be forced to raise their fees by an average of 36% by the year 2040.

In addition to this, a Ministry of Health survey indicates that as of the end of fiscal 2016, the annual replacement rate of old, corroded pipes was only 0.75%, far less than the essential rate, deemed to be 1.14%. Likewise, the spate of large-scale earthquakes with shaking reaching level 7 on the Japanese intensity scale in recent years has caused water stoppage in more than 1 million households, extending over several months in some cases.

There are three major reasons for this situation: population decline, aging facilities and infrastructure, and the increasing frequency of major natural disasters.

Japan’s population peaked at 128 million in 2008 and has been declining ever since. According to 2017 statistics compiled by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Japan’s total population is expected to drop to 90 million by 2063, and 60 million by the year 2100.

Water demand in Japan is already decreasing as compared to before 2000, due in part to the widespread use of water-saving appliances, and this trend is expected to accelerate as Japan’s population continues to decline. The resulting decline in revenue from water fees is already straining the resources of many water utility companies. This situation is being further aggravated by loss of technical knowhow as fewer and fewer young workers enter the field. Japan’s declining population is making it increasingly difficult for the utilities to secure the human resources they need.

The greatest asset of most water utility companies is their underground infrastructure of water pipes. Japanese law sets a 40-year service life for these pipes, though, and their value depreciates over this time. While depreciation costs remain on their books, water utility companies are expected to cover those costs with income from water fees. Once the depreciation period is passed, however, there is no longer a need to list it as a cost, and hence it should be possible to keep water fees down. Water supply is an essential service for daily life and there is strong social pressure to keep the fees low. What has happened is that badly needed pipe replacement has been put off in many cases to meet this demand.

The expansive piping systems installed during the years of Japan’s rapid economic growth have long since exceeded their legally mandated durability and are deteriorating further. Of course, just because they have outlasted their service life does not mean these pipes are no longer usable, but their age makes them frail and vulnerable to major damage caused by natural disasters. Scheduled replacement, however, requires massive investment of funds and technically capable human resources.

Japan is constantly buffeted by earthquakes, typhoons, and heavy rainfall. Durable and sturdy infrastructure and facilities that can withstand these natural disasters are required, but again, this means there must a major infusion of funds.

Consolidated Services and Public-Private Partnerships

The only way to overcome this difficult situation is to consolidate services over wider areas and promote partnerships between public- and private-sector actors. As of March 2017, Japan had 1,263 water utility companies, with 818 or 64.8% of these companies serving populations of less than 50,000. There are also an additional 707 companies providing small-scale systems that supply water to populations of less than 5,000. As this indicates, Japan’s water utilities industry comprises a lot of small-business enterprises. Waterworks are, in fact, an intensive industry in which costs go down and efficiency goes up when facilities are consolidated. With Japan’s dwindling population, the only option for survival is for neighboring water utilities to consolidate and optimize their resources.

The need for consolidation to provide wide-area services is not restricted to neighboring companies. Figure 4 shows the flow and range of water and sewage services. As the chart shows, in addition to consolidation there is a need for vertical integration of water supply and tap water provision operations, multi-utility operations combining waterworks and other public utilities, and the consolidation of tap water and sewage system operations. There are already a number of cases of vertical integration of water supply and tap water operations, not a few of which have found this to be an effective way of cutting costs.

Public-private partnerships are not only helping to supplement the dwindling number of workers in the field but are also introducing better management skills. Japan’s water systems are managed by local municipalities, and the utility companies have little say in personnel matters. The common practice of rotating municipal workers among different divisions makes it difficult to develop waterworks management knowhow and expertise. Private-sector management skills and R&D capacity to develop new technologies are critical resources for future waterworks businesses. Building equal partnerships between public and private entities looks to be the best way to ride out the current waterworks crisis.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Replacing a corroded waterpipe, December 24, 2016. © Yomiuri Shimbun/Aflo)