Legends: Japan’s Most Notable Names

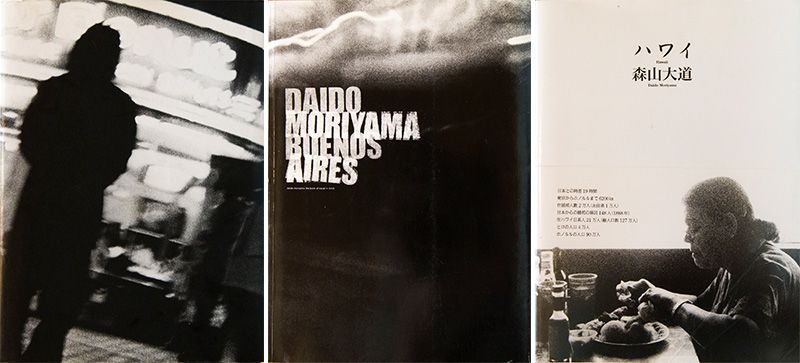

Moriyama Daidō: Photographer with the “Eyes of a Stray Dog”

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A portrait of the photographer. (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

A portrait of the photographer. (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

Exhibits by modern Japanese photographers have become common at art museums and galleries in all parts of the world since the 1990s. Moriyama Daidō stands alongside Araki Nobuyoshi as one of the most popular artists featured in these shows. Recent years have seen a number of large-scale Moriyama exhibitions, including a two-man exhibition with William Klein at the Tate Modern in London in 2012 and a one-man show, “Daidō Tokyo,” at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris.

Many young photographers in Japan, as well as their counterparts elsewhere in Asia, Europe, and other regions of the globe, have been strongly influenced by Moriyama’s black-and-white snapshot style that captures its subjects with, as he himself described it, “the eyes of a stray dog” wandering the streets. He is rightly called one of modern Japan’s major photographers.

Beginnings as a Graphic Designer

Moriyama Daidō was born in 1938 in Ikeda, Osaka Prefecture. His father worked in an insurance company, and his job caused the family to move often when Moriyama was a child—to Shimane, Chiba, Fukui, back to Osaka, and onward to still more of Japan’s prefectures. Moriyama has said that his frequent changes in school never let him get too close to the surrounding communities, and he often spent his afternoons after school wandering around whatever town he was in. The formative experiences of that time may be one of the reasons he later became fixated on street snapshots.

In 1955 Moriyama dropped out of Kōgei High School, a municipal school in Osaka, and began working as a freelance graphic designer. His experiences at that time came to be used in his later photographs—at first glance his snapshots appear to have a rough, unstable composition, but he then crops and prints them with keen attention to every detail, striking a fine balance that utilizes the skills he gained as a designer.

As a young man, however, Moriyama found it difficult to bear sitting at a desk all day designing matchboxes or calendars. As he came into contact with photographers as part of the job, he developed a strong interest in taking his own pictures. In 1960 he became an assistant in the studio of Iwamiya Takeji in Osaka. During his time in the Iwamiya studio, he was strongly affected by William Klein’s 1956 photography collection New York. He also studied street snapshots with Inoue Seiryū, a photographer several years older than him who was known for his documentation of Kamagasaki, an area of Osaka home to many day laborers. The idea of becoming a photographer and working on a larger stage grew in him.

In 1961 Moriyama moved to Tokyo. There he wanted to be involved in some way with the Vivo photographers’ group formed by Tōmatsu Shōmei, Narahara Ikkō, Kawada Kikuji, and others, but it had already disbanded. Moriyama was then picked up by Hosoe Eikō, one of the members of Vivo, to be an assistant. At the time that Hosoe was in the middle of producing the photo collection Barakei (1963), modeled on Mishima Yukio; Moriyama was able to learn a range of shooting and darkroom techniques. By the time he married in 1964, he had become an independent freelance photographer. Of course, he had virtually no work.

“Inu no machi” (“Misawa,” 1971). Taken in Aomori Prefecture, this shot would be a defining moment in the career of the photographer, who came to see his own street-photography gaze as similar to the stray dog’s somewhat furtive, but intensely interested, look. (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

“Inu no machi” (“Misawa,” 1971). Taken in Aomori Prefecture, this shot would be a defining moment in the career of the photographer, who came to see his own street-photography gaze as similar to the stray dog’s somewhat furtive, but intensely interested, look. (© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation)

Photos as an Indictment of the Times

Moriyama lived in Zushi, Kanagawa. He would often go to the nearby city of Yokosuka, home to an American naval base, taking snapshots of the unique street atmosphere in that area. He took these photos to a magazine called Camera Mainichi. There they captured the attention of legendary editor Yamagishi Shōji, who decided to print them in a nine-page spread entitled “Yokosuka” in the August 1965 issue of the magazine.

This was essentially Moriyama’s debut, and the reaction was huge. Moriyama began publishing photos regularly in Camera Mainichi and Asahi Graph. The Japan Photo Critics Association presented him with its Newcomer’s Award in 1967 for a series of biting works on local Japanese sensibilities, and his first printed collection, Nippon gekijō shashin chō (The Japan Theater: A Photo Book), was published in the following year. That same year he was involved from the second issue in Provoke, a privately published magazine started by Nakahira Takuma, Taki Kōji, Takanashi Yutaka, and others as “provocative fodder for thought.”

Moriyama’s run continued. In 1969 his experimental work, Accident, which mixed copied poster and advertising flyer photos with snapshots taken on the street, was serialized in Asahi Camera. In 1970 he published nudes in Weekly Playboy, alternating each week with Shinoyama Kishin. From a stay in New York with Yokoo Tadanori in 1971, he published a series entitled Nani ka e no tabi (Journey Toward Something) in Asahi Camera. His activity in this period peaked with the 1972 photo collection Shashin yo sayōnara (Goodbye, Photography), a collection of grainy, out-of-focus photos in which it was mostly unclear what was being shown.