Maeda Corporation’s Fantasy Marketing Department: Real-World Inspiration from Anime Dreams

Society Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Turning to Fantasy for Business Chances

Real-world contractor Maeda Corporation provided the inspiration for the 2020 Maeda Kensetsu Fantajī Eigyōbu (The Maeda Corporation Fantasy Marketing Department). The model for Asagawa Teruyuki, the leader of the Fantasy Marketing Department in the movie, is Iwasaka Teruyuki, the current head of business incubation at Maeda’s ICI Center. After studying engineering at Nihon University, Iwasaka started to work for Maeda Corporation in 1993. He was involved in the construction of the Tokyo Bay Aqua Line, completed in 1997.

Iwasaka came up with the idea of the Fantasy Marketing Department in 1998. He had been astonished at the sight of Honda Motor’s bipedal P3 robot, the prototype for the company’s famed ASIMO. He had a particular interest in robotic technology but, more than that, he was envious as he looked at everyone, from children to elderly people, clapping with joy at the sight of it.

“To be honest, I was jealous. I wondered why a construction company couldn’t generate that kind of impact. And that’s when I had a flash of inspiration. Maybe we couldn’t build robots, but we could certainly build hangars for robots!”

Born in 1968, Iwasaka is part of the Mazinger Z generation, raised on manga and anime about the gigantic battle robot of the same name. He thought of the opening sequence of the animated TV show, in which a pool of water splits cleanly in half and Mazinger Z suddenly rises up out of it.

At the time, the construction industry in Japan was in a dark place as it struggled with a workplace image people called the “three Ds”—dirty, difficult, and dangerous—combined with poor demand as a result of the bursting of the economic bubble. Even Maeda, which had worked on large-scale projects including dams, tunnels, and power plants during the high-growth 1960s and 1970s, was uneasy about what the future held.

That said, Iwasaka was convinced that despite the slump, there had to be a “blue ocean” somewhere—an undeveloped market where the firm could set sail with no competition. This turned out to be demand emanating from manga and anime, the world of fantasy.

A Novel Approach to Explaining Construction

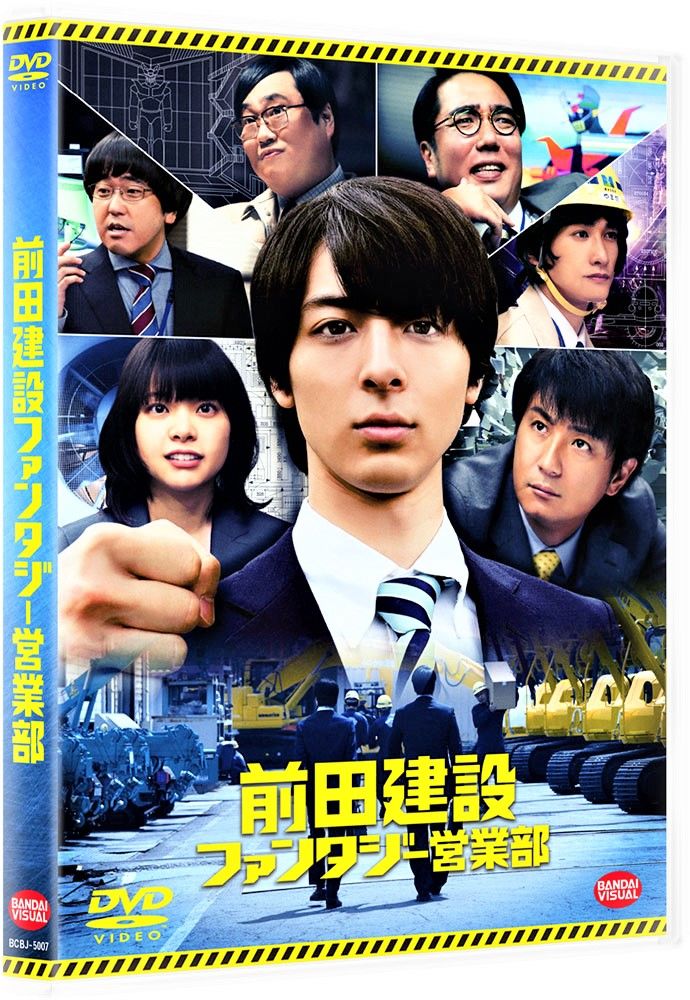

Following its theatrical release early in 2020, Maeda Kensetsu Fantajī Eigyōbu (The Maeda Corporation Fantasy Marketing Department) came out on physical media in September. (© Maeda Corporation/Team F/Dynamic Planning/Tōei Animation)

After nursing the idea in his head for a time, Iwasaka and the Maeda PR team petitioned the company’s board to create a “Fantasy Marketing Department” in 2002.

Iwasaka recounts: “Our aim was to use the imaginary—the megastructures that appeared in the animation and manga we used to enjoy in the past—to help even people who didn’t have the slightest interest in the construction business understand our approach when building megastructures, from the early planning stage right down to how we bring the whole thing together in the formal project estimate. To achieve this, we’d create a Fantasy Marketing Department, with its own section on our website. We’d post the various steps once a month until an estimate was ready, and we would announce the results in about half a year.”

However, having heard the presentation, his superiors all looked puzzled. “Iwasaka, why is it that we have to build Mazinger Z?”

“We can’t build Mazinger Z!” was his reply. “That’s not what I’m taking about. I’m talking of the hangar out of which Mazinger rises! And we wouldn’t actually be building it!”

At the beginning, the executives paid scant attention. They wondered what significance this could possibly have for the company. First of all, it didn’t seem right to release estimates, even if they were for an imaginary structure . . . But in the end they were caught up In Iwasaka’s enthusiasm, and approved the project on the condition that it would be done outside office hours. Needless to say, the Fantasy Marketing Department wasn’t a proper department, and the work was done after Iwasaka and his comrades clocked out, either in a company meeting room or at Iwasaka’s home.

Overcoming the Biggest Barriers

Right from the start, the project faced difficulties. Iwasaka had been told by his colleagues that if he was going to use Mazinger Z as his theme, he had to clear any copyright issues, and so he approached a major advertising agency to ask for help.

The agency representative he spoke to told him with a smile, “Wow! That’s a great idea. I’ve never heard of such a project before. Normally, it’s requests to use the heroes or the robots as a backdrop. It shouldn’t cost any more than a few tens of millions of yen.”

Iwasaka remembers: “The minute I heard that sum, I felt dizzy.” A project that was basically like a club activity didn’t come with that kind of budget. Having only just gotten underway, was it already doomed?

However, the ad man must have felt sympathy on seeing how crestfallen he was, and as he walked him back to the elevator, he mumbled as he pushed the down button: “You know, if the creators of media properties tell us that they’re OK with something, there is really nothing we can say to that.”

Basically, he was kind enough to encourage Iwasaka by telling him to get Nagai Gō, the creator of Mazinger Z, on his side.

Iwasaka was in luck. When he looked up the address for Tōei Animation, which held the copyright, he realized it was close to Maeda’s offices. When he met with the head of the relevant division, it turned out that his father had worked in construction and so he had a soft spot for the field. He arranged a meeting with the head of production for Nagai’s studio, and Iwasaka soon had his approval in hand.

Hard Work for Zero Profit

Even if it was for an imaginary structure, they couldn’t use slapdash accounting in putting the estimate together. Just like when building an actual tunnel or dam, they had to decide where the hangar would be built, what size it would be, and what the interior configuration would be. They would then draw up plans that were faithful to the original to the last detail, and calculate the cost of the labor, materials, machinery, and transport needed for the work.

They also had to obtain the cooperation of other companies. And this had to be free of charge. For example, Mazinger Z rises up 25 meters in 10 seconds from the hangar, like a stage elevator. This meant getting input from a company specializing in industrial-grade elevators.

Iwasaka and his team established a set of rules for when making requests to other companies. The first was not to approach the company using official sales routes, but rather to use email and postal channels for the general public to make their overtures. They wanted to cooperate not with people with whom they already had a business relationship, but with those who would say “That sounds like fun, let’s do it!”

Checking through all of the 92 anime episodes, they realized that in episode 69, Mazinger Z suddenly moves sideways inside the hangar. This complication seemed to pose a major problem. But when they asked the partner company to redo the design, the response was enthusiastic and immediate, and they soon had various suggestions to work with.

In spite of their arduous work, though, website traffic was not going up at all. This was before the time of social media. Shoulders sagged among Iwasaka and his crew, who thought they had run out of ideas.

At last, though, when the last post giving the results—“Construction cost ¥7.2 billion, construction time was 6 years, 5 months”—went up, it was picked up as a “today’s recommendation” favorite by Yahoo Japan. Everything changed overnight. There was such a rush to access the site that the company servers almost went down. After that, the story was picked up by newspapers, television, and magazines, and even made into a book. The Fantasy Marketing Department had been catapulted into fame.

The team’s second project, the “Earth Departure Viaduct” from Matsumoto Leiji’s Galaxy Express 999, and its fifth, the Jaburō Earth Federation Forces military complex from Mobile Suit Gundam, also became big hits and were turned into books. There have been nine projects so far.

Books based on project 1, the Mazinger Z hangar, and project 2, the Galaxy Express 999 launch mechanism, published by Gentōsha. (Photos by author)

A “Real Fantasy” Marketing Department Takes Shape

Iwasaka is currently head of the Incubation Center at Maeda’s ICI Center in Toride, Ibaraki Prefecture.

The center is the platform for the open innovation that is being promoted by Maeda Corporation. Open innovation refers to the creation of new business models that bring together of companies in different sectors, universities, municipalities, and venture businesses to generate ideas and knowledge. This is exactly what Iwasaka and his Fantasy Marketing Department have been doing, and the ICI Center could even be called Maeda’s “Real Fantasy Marketing Department.”

The ICI Center has a futuristic look, rather like the mammoth hangar featured in Mazinger Z. (Photo by Maeda Corporation)

Iwasaka Teruyuki says, “I’d like young employees to suggest all kinds of new directions for the Fantasy Marketing Department.” (Photo by author)

“The days when construction simply meant building something are gone. It’s now a question of making best use of new technologies such as IT and AI to see what kind of services can be provided with what kind of infrastructure. That’s something construction companies cannot do alone. What we have done with the Fantasy Marketing Departure is useful to us now,” explains Iwasaka.

The Fantasy Marketing Department got under way at the start of the millennium, when many Japanese companies were still caught up in old work values, with plenty of overtime and working on holidays were seen as a virtue. The character Asagawa in the movie is a throwback to that older time, being a manager likely to be called a “black boss” nowadays for the demands he makes of his workers. But when Iwasaka asks students at the university where he is a part-time lecturer what they think of the movie, surprisingly, fewer than 10% think that there is an issue with the way Asagawa and his team work.

“This movie comes with English subtitles,” notes Iwasaka, “and I would like all kinds of people overseas to see it. I’d really like to talk about differences in perception concerning work and how to bring about innovation.”

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: The cast of The Maeda Corporation Fantasy Marketing Department. Asagawa Teruyuki, played by Ogi Hiroaki, at top left, is presented as a passionate manager pulling his team along, but Iwasaka notes that everyone on the real team was keen from the very beginning. © Maeda Corporation/Team F/Dynamic Planning/Tōei Animation.)