A Brief History of Japanese Professional Wrestling

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s First Professional Wrestler

Matsuda Sorakichi (1859?–91) is generally recognized as Japan’s first professional wrestler. The former rikishi, or sumō wrestler, made his ring debut in the United States in 1883. Matsuda did not remain the only Japanese grappler, however, with other countrymen, as well as Japanese-Americans, following in his footsteps during the latter nineteenth century to show their strength in the squared circle. One of these was Matsuda’s friend and former rikishi Mikuniyama, who also went by his given name, Hamada Shōkichi. He and Matsuda staged an exhibition of Western-style professional wrestling in Tokyo’s Ginza district in 1887. Although the event failed to pique the interest of Japanese at the time, it has historical significance as being the first professional wrestling event in the country.

The Era of Rikidōzan

Japanese professional wrestling, or puroresu, as it came to be called for short, began in earnest in 1951 with the debut of star wrestler Rikidōzan. Anti-American sentiment remained strong following Japan’s defeat in World War II, and fans would crowd around televisions to cheer on their hero as he felled Western opponents with his trademark karate chop. Rikidōzan established the promotional organization Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance in 1953, helping lift the popularity of the sport to the same level as the other national obsessions of professional baseball and sumō.

Fans crowd around a television to watch a live broadcast of a match in Tokyo 1954. The start of commercial broadcasts the same year helped spread the popularity of professional wrestling. (© Yomiuri Shimbun/Aflo)

Fans crowd around a television to watch a live broadcast of a match in Tokyo 1954. The start of commercial broadcasts the same year helped spread the popularity of professional wrestling. (© Yomiuri Shimbun/Aflo)

Rival Organizations

The JWA continued to operate following the death of Rikidōzan in December 1963, but its dominance was challenged by the appearance of two rival organizations, Tokyo Pro Wrestling and International Wrestling Enterprise.The JWA eventually folded after star wrestlers Antonio Inoki and Giant Baba left to form their own promotions, New Japan Pro Wrestling and All Japan Pro Wrestling, respectively.

Puroresu continued to change and develop into the 1970s. Inoki, who touted a “strong style” that included aspects of martial arts, raised his image by participating in mixed-skill bouts with such opponents as boxing legend Muhammad Ali and Olympic jūdōka Willem Ruska. Baba also continued to build his popularity as a grappler, using connections with US-based National Wrestling Alliance to stage matches featuring big-name foreign wrestlers. The IWE took a different tack in building its fan base, distinguishing itself from other organizations through such unique strategies as bringing over European wrestlers employing new and different styles and staging fan-rousing “deathmatches.”

The 1980s saw the rise to prominence of Inoki and Baba protégés Jumbo Tsuruta, Tenryū Gen’ichiro, Fujinami Tatsumi, and Chōshū Riki, along with Sayama Satoru, who debuted as the enigmatic Tiger Mask. The founding of the short-lived Universal Wrestling Federation in 1984 established the prominent hybrid shoot style of wrestling and opened the door to mixed martial arts bouts.

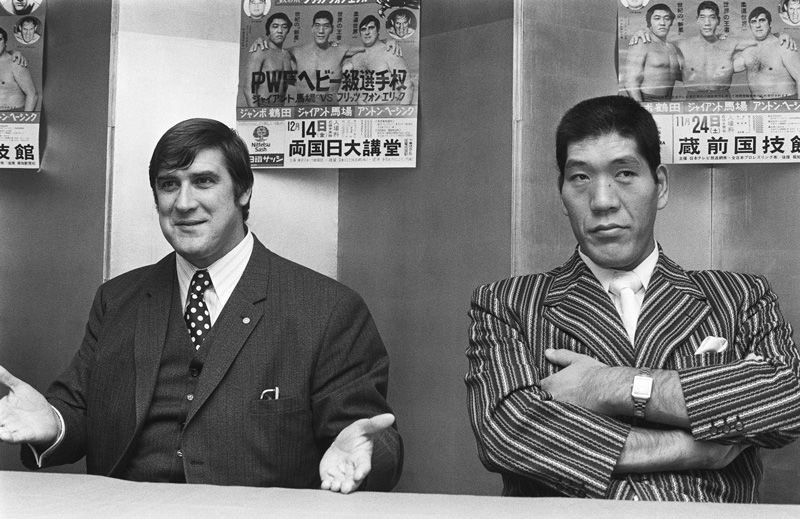

Olympic jūdō champion Anton Geesink (left) is joined by Giant Baba as he explains his decision to move to professional wrestling during a press conference in Japan in 1973. (© Jiji)

Olympic jūdō champion Anton Geesink (left) is joined by Giant Baba as he explains his decision to move to professional wrestling during a press conference in Japan in 1973. (© Jiji)

Upsurge of New Groups but a Dwindling Fan Base

The 1990s saw many dramatic changes in professional wrestling. The sport’s popularity began to wane, with the legendary Baba and Inoki largely stepping out of the limelight. Broadcasts of matches were moved from prime time to late-night slots, and wrestling genres became increasingly specialized. The establishment of Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling in 1989 by Baba apprentice Ōnita Atsushi inspired a throng of new “indie” organizations to throw their hats into the ring.

While wrestling’s overall popularity was on the decline, promotions were able to draw massive crowds by hosting events at Tokyo Dome and other large-scale venues. US wrestling was moving toward televised events, however, making it increasingly difficult to secure foreign wrestlers for matches in Japan. As a result, puroresu shifted away from its mainstay of pitting Japanese wrestlers against foreign foes to focusing on bouts between Japanese grapplers.

Leading the NJPW during the 1990s were the “Three Musketeers” (Tōkon Sanjūshi), a trio consisting of Chōno Masahiro, Mutō Keiji, and Hashimoto Shin’ya. The top wrestlers for the AJP were the quartet known as the “Four Heavenly Kings” (Shitennō): Misawa Mitsuharu, Kawada Toshiaki, Kobashi Kenta, and Taue Akira. But mixed fighting series like K-1 and Pride emerged, grabbing the limelight from puroresu as “alternative” combat sports. Many professional wrestlers took inspiration from Inoki’s strong style to try their hand at the new mixed-style bouts. Few, however, enjoyed success, and their poor showing only hastened the decline in the popularity of puroresu.

In 1997, Japanese pro wrestling suffered its first ring fatality when Plum Mariko of the women’s promotion group JWP Joshi Puroresu died from head trauma during a tag team bout.

Regional Groups and Wrestling as Entertainment

In the early 2000s, the old guard AJP and NJPW were joined by two new promotions as the dominant forces of pro wrestling. Misawa took over the helm of the AJP after the death of Baba in 1999, but he left the AJP over management disagreements with Baba’s widow, Baba Motoko, taking most of the wrestlers with him when he formed a new promotion, Pro Wrestling Noah. The AJP sought to stay alive by staging bouts with grapplers from the NJPW. It was helped along in its fight for survival by Mutō, who transferred to the group in 2002 and took over as president later the same year. Hashimoto established Pro Wrestling Zero-One after being let go by the NJPW following a failed attempt to form an affiliate organization. Spurred along in part by AJP-NJPW mixed matches, the practice of holding bouts between wrestlers from major and independent groups became standard practice throughout the puroresu world.

Over the last decade, Japan has seen the popularity of major US promotion World Wrestling Entertainment steadily grow. This has prompted a similar domestic trend toward promoting professional wrestling as sports entertainment. Independent groups like Fantasy Fight Wrestle-1 and Hustle Entertainment have led the way in this movement. In 2006, Misawa established the Global Professional Wrestling Alliance with the goal of unifying the diverse wrestling organizations in Japan. The coalition failed to get a foothold, however, and ceased most of its activities after only one year. While the early 2000s saw the emergence of a third generation of professional wrestlers, they were unable to match the popularity of wrestlers from the previous generation, notably the Three Musketeers and the Four Heavenly Kings, and bouts featuring these older stars continued to be the mainstay of the sport through the first half of the decade

In 2005, however, Hashimoto died suddenly, followed by Misawa in 2009. Meanwhile, other members of the star trio and quartet left their organizations or suffered injuries. So since the latter part of the 2000s, as the Three Musketeers and Four Heavenly Kings became unavailable for regular bouts, what might be called a fourth generation of wrestlers rose to prominence. And as a result of these developments, the power structures of the various promotions have been shifting.

Major Professional Wrestling Organizations

Table produced by Nippon.com using information from the magazine Nikkan Spa.

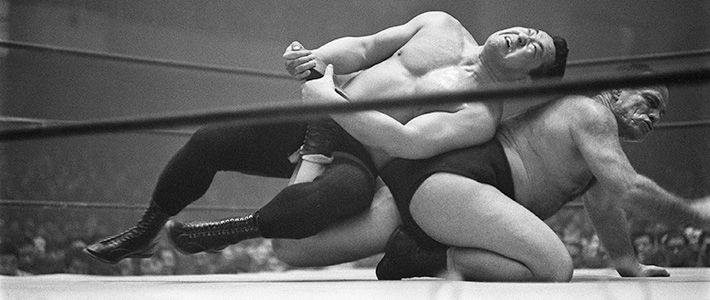

(Banner photo: Rikidōzan [left] applies a hold to an opponent. © Jiji.)

Related Tags

professional wrestling puroresu Rikidōzan Antonio Inoki Giant Baba Tōkonsanjūshi three musketeers Shitennō four heavenly kings mixed martial art strong style deathmatch All Japan Pro Wrestling New Japan Pro Wrestling International Wrestling Enterprise Japan Pro Wrestling Alliance