“The Making of a Japanese”: Ema Ryan Yamazaki Movingly Documents Elementary School Life in Japan

Culture Society Cinema- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japanese society is admired for its orderliness—prompt trains, litter-free streets, lost valuables returned intact. But what is behind the high degree of discipline and structure? Director Ema Ryan Yamazaki explores the roots of Japan’s famed social harmony in her new documentary The Making of a Japanese, a heartwarming portrait of elementary schoolchildren learning to get along in the miniature society of the classroom.

Yamazaki spent a year filming at Tsukado Elementary School in Setagaya, Tokyo, focusing her lens primarily on first and sixth graders there. Although the rhythms of school life have been disrupted by the pandemic during the period she covers—face masks are mandatory, lunches are eaten in silence behind plastic shields—the familiar routines of the Japanese classroom carry on. The film shows how alongside academics, children carry out assorted classroom responsibilities ranging from cleaning to serving lunches to assisting teachers, each duty assigned to a different group of pupils on a revolving basis. Yearly events like the school’s sports festival also see the students take an active role in preparations and execution.

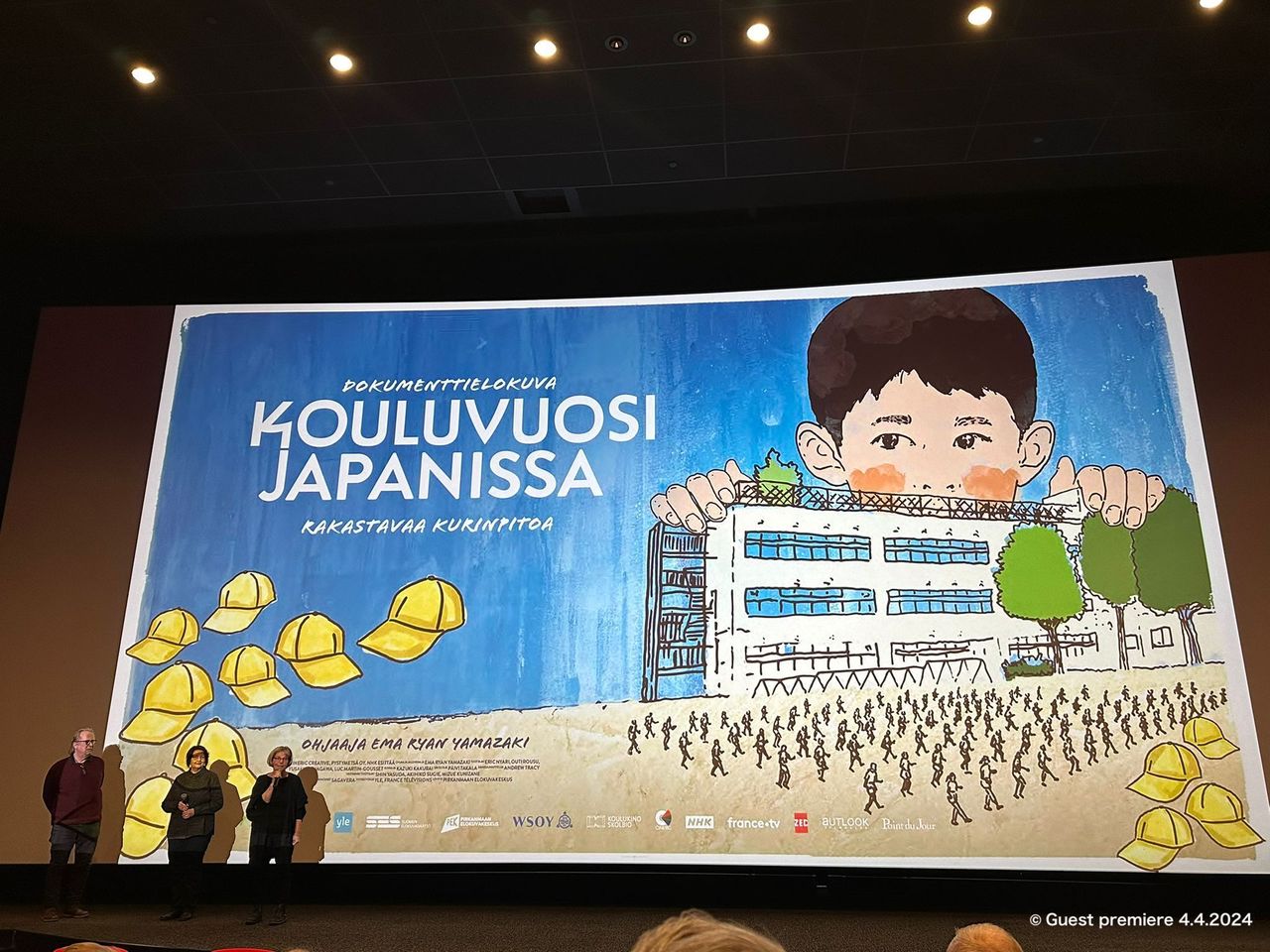

The film perhaps appeals more to foreign viewers than Japanese, who are familiar with the responsibilities asked of elementary schoolchildren. For moviegoers outside Japan, the regimented aspect of the education system portrayed in the film has sparked fascination and admiration. Since its release in December 2023, the documentary has earned accolades at film festivals in Europe and the United States. In Finland, it was shown at 20 venues, enjoying a four-month run in Helsinki, and in South Korea it was aired on television.

A teacher shows her students the proper way to handle a broom. (© Cineric Creative/NHK/Pystymetsä/Point du Jour)

Students serve lunch to their classmates, a duty that everyone shares in turn. (© Cineric Creative/NHK/Pystymetsä/Point du Jour)

Lessons for Life

The documentary’s title suggests a critical study of the Japanese education system, but Yamazaki’s film, like her previous works such as the 2019 Kōshien: Japan’s Field of Dreams, is an exploration of the culture she grew up in rather than a statement. “Schools everywhere strive to prepare children for the future,” she explains. “I would say that children in Japan and the West are more or less the same up to the age of six. Once they reach twelve, though, there are some obvious differences.” In particular, she points to the development of group-oriented thinking among Japanese children. “In Japan, this is instilled in the classroom by assigning roles and responsibilities that foster the collaborative skills students will need to get along in Japanese society.”

Yamazaki can speak to the contrasting educational approaches of Japan and the West, having experienced both. She attended a public elementary school in Osaka through the sixth grade and went to a private international school in Kobe for junior high and high school. As an undergraduate, she studied at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and remained in the Big Apple to pursue a career in film.

Growing up, Yamazaki, whose father is British and mother is Japanese, says she considered herself to be Japanese foremost, but that her mixed heritage inevitably made her stand out in elementary school. “I was the only kid at school with light hair and who could speak English,” she recounts. “I knew this made me somehow different from my classmates. I could never quite put my finger on it, though, and for a long time now, I’ve been exploring what it means to be Japanese.”

Working in the United States, Yamazaki admits to feeling nonplussed at regular praise from colleagues over things like being on time, hard-working, and a team player, traits that to her were second nature. “When someone would make a comment, I would wave it off, saying that’s just how Japanese people are.” Around 10 years ago, though, she started to be more introspective and began to explore who she was as a person. This process has led to many precious insights. “The more I examined my thoughts and feelings, I realized that so much of who I am comes from the lessons I learned while at Japanese public elementary school.”

Ema Ryan Yamazaki. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Yamazaki’s most vivid memory from elementary school is the annual sports festival that took place in her sixth-grade year. One of the traditional highlights of the event was a lively gymnastics display by the older students. The crowning formation was a human pyramid featuring tiers of students precariously balanced atop one another. Strength, balance, and teamwork were required, and Yamazaki had her doubts at first, saying, “I didn’t think we had a chance of pulling it off.” With steady effort, though, the pyramid slowly came together. “We practiced again and again in weeks leading up to the event, and our confidence grew as we improved.”

On the day of the festival, Yamazaki says that nerves were on edge but that she and her classmates were determined to succeed. The performance went off without a hitch, with the grand finale drawing avid cheers from parents and others gathered for the event. “When we finished, my friends and I hugged and cried with joy and relief. It was very emotional.” Looking back, she recognizes how much of an impact the experience had on her class. “It was an intense challenge for kids who were just eleven and twelve, but we gained an amazing sense of accomplishment. The experience taught us that we could overcome whatever challenges we faced so long as we came together and put our minds to it.”

As Yamazaki’s story illustrates, school events like sports festivals and music festivals play an important part in the social development of schoolchildren. “They are recurring landmarks in a Japanese child’s six years at elementary school,” she notes. Transferring to international school in junior high, Yamazaki says she entered a completely different world dominated by Western ideas of individualism. “There was nothing about working together as a group. Instead, it was all about how we were unique or different. We didn’t even practice ahead of our sports festival but just showed up and ran our races.”

Experiencing such contrasting approaches to education inspired Yamazaki to make her documentary in an attempt to show the world what it is like to be an elementary school student in Japan. The project took time to come to fruition, though, as finding a school willing to open its doors to such an endeavor proved more difficult than she had expected. She spent six years searching in vain before eventually gaining the approval of authorities in Setagaya—the proposal took advantage of the city hosting the US Olympic contingent and framed the project as a way to foster international understanding in line with the Tokyo Games.

Consideration, Cooperation, Accountability

The film is filled with smile-inducing storylines—one about a first grader learning the cymbal part for a performance of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” Yamazaki turned into the short documentary Instruments of a Beating Heart, which has been nominated for an Academy Award. But Yamazaki keeps the spotlight on the rigid elements of the Japanese education system. In one scene, a first-grade student monitor diligently checks if footwear is neatly arranged in shoe cupboards, while in another, pupils rehearsing for graduation are admonished to walk and move in just the right way. There are more than a few moments that prompt questions about how much conformity is too much. A visiting university professor speaking to school staff during a seminar cautions that Japan’s educational focus on social cohesion is a “double-edged sword” that can lead to ostracization and bullying.

In her observational approach, Yamazaki does not try to answer these questions, instead allowing viewers to draw their own conclusions. She says that if the film makes any point, it is that in their group-oriented approach, Japanese elementary schools succeed at fostering empathy and cooperation in students. “Children learn to take an interest in what their classmates are going through, as if their troubles were their own.”

The documentary has enjoyed a warm international reception. “So many people have reached out to say the film moved them and to express their admiration for Japanese children,” says Yamazaki. “A viewer in Finland even went so far as to declare that the documentary was a textbook on community building and had inspired people to rethink approaches to education.” She chalks up such responses to a reevaluation of the individualistic values stressed in many education systems. “People see more and more children who are self-absorbed, and I think they look to Japan as offering a hint for striking a healthier balance.”

A screening of The Making of a Japanese in Finland. (© Cineric Creative/NHK/Pystymetsä/Point du Jour)

A screening of The Making of a Japanese in Finland. (© Cineric Creative/NHK/Pystymetsä/Point du Jour)

Yamazaki was particularly surprised by the number of viewers who drew a parallel with the reputation of Japanese soccer fans at past World Cups for cleaning stadiums following matches. “Honestly, I had no idea it was such a huge story, but people just about everywhere mentioned it. I think the movie confirmed impressions of Japanese as being detail-oriented and for holding themselves to high standards.”

Yamazaki says that the long filming and editing process revealed to her a glimpse of what it means to be Japanese. She characterizes one aspect of this as the emphasis on taking responsibility for one’s surroundings. “Elementary school students are charged with a seemingly endless list of tasks,” she explains. “One group of pupils is responsible for opening and closing the windows, another for serving lunches, yet another for cleaning the classroom, and so on. The children carry out their duties with such diligence that you’d think it was ingrained in their DNA.” Yamazaki admits to being conflicted on this last point. “Developing a sense of purpose is a plus in most respects, but in Japan this goes hand in hand with conformity, and there are more and more people today who feel boxed in by the rigidness of Japanese society.”

Yamazaki recognizes that every society has its own approach for instilling cultural values, while noting that few go to the extent that Japan does. She points, for example, to the Japanese program Hajimete no otsukai—broadcast overseas as Old Enough!—and the surprise it sparked among many viewers regarding the errands preschool-aged children were able to handle around town on their own. “If I was to break down what it is to be Japanese into its central components, a sense of responsibility would certainly be one of them. There are good and bad facets to this, of course. But when it’s all summed up, I feel the positive aspects win the day.”

Film Information

- Director: Ema Ryan Yamazaki

- Running Time: 99

- Official Site: https://shogakko-film.com/

Trailer

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview and text by Ishii Masato of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Documentary filmmaker Ema Ryan Yamazaki during an interview in Shibuya, Tokyo, on January 15, 2025. © Hanai Tomoko.)