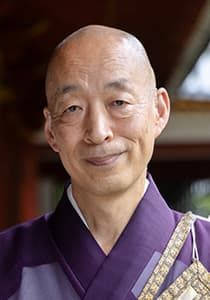

Tōdaiji Chief Abbot Hashimura Kōei on the Temple’s Past and Future

Culture History Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Praying for Peace for the Nation

The temple Tōdaiji was built during the Nara period (710–94) to pray for the nation’s peace and tranquility. Moved by the desire to save all sentient beings, Emperor Shōmu (701–56) ordered the creation of the temple’s principal image, Vairocana, in 752. Today this cast-bronze statue is known throughout the world as the Nara Daibutsu, or Great Buddha, and Tōdaiji is both the principal attraction in Nara, drawing many people from throughout Japan and the world, and the site of the Shunie, a rite of repentance performed every year in March. Hashimura Kōei became chief abbot in 2022, the 224th in a line that continues from the temple’s first abbot, Rōben (689–773).

“Tōdaiji and the Daibutsu share a history of more than twelve hundred years. Work on the Daibutsu began with the emperor’s proclamation in 743, in Shigaraki, in today’s Shiga Prefecture, where the imperial capital was briefly located. The capital was subsequently moved to Heijōkyō, in what is today Nara, and the casting of the Daibutsu resumed in the northeastern part of Heijōkyō, the site of Tōdaiji. According to the temple records called the Tōdaiji yōroku, casting of the statue began in 749 and construction of the Daibutsuden Great Buddha Hall was completed in 751. A grand ceremony to consecrate the figure took place in 752. The West and East Pagodas, the Lecture Hall, and the Monks’ Quarters were added later to complete the temple complex.”

At the time, smallpox originating on the Asian continent spread to Kyūshū and throughout the land, causing unprecedented disorder. Two epidemics, in 735 and 737, felled many nobles, including members of the powerful Fujiwara family. According to the eighth-century Shoku Nihongi chronicle, Emperor Shōmu believed that these calamities stemmed from his own poor behavior. In addition to reducing taxes, distributing rice, and lending funds to provide relief, with the nation’s future at stake, he sought to restore stability through the power of Buddhism by ordering the construction of the Great Buddha (Daibutsu) Vairocana.

“The emperor, believing that it was important to involve the entire populace in this difficult enterprise, appealed for help from the public. Some 26 million people, approximately half the population at the time, toiled for close to 10 years to build the Daibutsu and the temple. The itinerant monk Gyōki [668–749], who constructed bridges, dug ponds, and carried out other public works, attracted a wide following among the common people and was instrumental in organizing labor for the project. Thus, the Daibutsu truly symbolizes prayers for the nation’s prosperity.”

Chief Abbot Hashimura Kōei standing with the Daibutsu. (© Muda Haruhiko)

Signaling Japan’s Advancement

Over 10,000 people, including the emperor and his consort, monks, and officials attended a lavish ceremony to consecrate the Daibutsu. The “opening of the eyes” rite for the statue was performed by Bodhisena (704–60), an eminent Indian monk.

“There were both religious and political reasons for inviting Bodhisena to travel from India, birthplace of Buddhism, to perform the ceremony. At the time, Buddhism served as an international measure of cultural advancement in places such as India, China, and Korea. In modern terms, it’s similar to measuring the health of democracy in various countries. Buddhism was thus a major indicator signaling prosperity to outsiders. The Daibutsu was not only the symbolic guide and protector of Japan, it was also an important diplomatic signifier of the country’s cultural and technological might to other parts of Asia. According to the eighth-century Nihon shoki chronicle, an envoy from the king of Paekche on the Korean peninsula was dispatched to Japan to offer Buddhist statues and sutras in 552. The Daibutsu consecration ceremony held in 752 demonstrated that Japan had ‘arrived’ as a Buddhist country, and with the construction of a national system of monasteries and nunneries, that Japan had become the equal of China in terms of religion in a mere two centuries.”

Reconstruction Works

In 1180, the Daibutsu was damaged and the Daibutsuden destroyed in a fire resulting from war between the Taira and Minamoto clans. Nevertheless, the monk Chōgen (1121–1206), true to the teachings of the Buddha, enlisted the help of the court, warlords, and many ordinary people to repair the Daibutsu and rebuild the Daibutsuden. But disaster struck again: In 1567, when the Daibutsuden burned down during a skirmish by warring clans, the Daibutsu’s head and arms fell off, and the figure’s torso melted in the heat of the fire. For the next 100 years, the statue was left at the mercy of the elements. It was only in the mid-Edo period (1603–1868) that the monk Kōkei (1648–1705), distressed at the state of the Daibutsu, led a drive to undertake restoration.

“During these two reconstruction projects, many people came forward to help repair the Daibutsu and rebuild the Daibutsuden,” says Hashimura. “Although damage due to war and other circumstances could not be helped, people fervently believed that helping restore the Daibutsu would earn them merit. In the first restoration, during the Kamakura period [1185–1333], the Daibutsuden was rebuilt to its original late Nara-period width of 88 meters. In the Edo period restoration, however, the structure’s width was scaled back to 57 meters due to a lack of funds and materials. Even so, I believe that the sentiments of people from thirteen centuries ago have been carried into our own century. The merit continuously earned by long-ago people’s deeds connects with Emperor Shōmu’s wish that Tōdaiji bring eternal happiness. We can pray to the Daibutsu today thanks to this legacy perpetuated by previous generations.”

The current Daibutsuden was reconstructed during the Edo period. (© Muda Haruhiko)

The Path to Knowing Oneself

In addition to the Daibutsu, 24 other figures designated national treasures, including a standing figure of Amoghapasa, a manifestation of Kannon, are in Tōdaiji’s possession. Tōdaiji is included among the Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara, inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1998.

Hashimura explains the history of the faith. “The Three Ages of Buddhism start with shōbō, the first 500 or 1,000 years after Buddha’s passing. This was the age when disciples who attained enlightenment through ascetic training or study could still appear on Earth. Zōbō refers to the second 500 or 1,000 years, in which Buddhist teachings and ascetic training existed, but no disciples attained satori. Mappō is the age following zōbō, when Buddhist teachings exist but no one will achieve satori, even after following ascetic training. In Japan, it is believed that we entered the mappō age in 1052.”

The reign of Emperor Shōmu corresponds to the zōbō age. Since the Buddha or disciples having attained satori were not present on Earth in that age, people believed they could earn merit by memorializing the remains of the Buddha. Temples had their origins in the pagodas housing the Buddha’s remains built by the faithful; the pagodas served as sites for remembering the Buddha, meditating, and carrying out ascetic practices. On the day that Shōmu issued his edict to construct the Daibutsu, he declared that the realm had incontrovertibly entered the age of zōbō. It was on that basis that Shōmu established provincial temples, constructed a seven-story pagoda, and had the Daibutsu created.

The character zō in zōbō means “resemblance” or “likeness,” as Hashimura explains. “Figures were created in the likeness of Buddha or the bodhisattvas as an aid for recollection during ascetic training. At Tōdaiji, we have protected these likenesses since the temple’s founding, and we pay great attention to two things. The first is preserving and repairing the figures because they are a cultural legacy. We maintain them, reapplying lacquer or replacing damaged parts as necessary. The second is keeping alive people’s connections with these figures. Buddhist statues are not mere wood carvings; they serve to transmit the Buddhist teachings of faith, compassion, and other attributes. They embodied the prayers of the people since ancient times and were part of everyday life. But modern lifestyles make it more difficult for people today to embrace the spirit of prayer. Although it may not be possible to live like our forebears, I hope that people will pause before the statues with a calm heart and experience the mercy of the Buddha.”

Encountering a Different World

Although Hashimura took holy orders at the age of 13, in his university years he harbored doubts about life as a Buddhist priest. The turning point came when he read a book on Buddhism in English by Thich Nhat Hanh, a Zen monk and global Buddhist leader born in Vietnam. Espousing nonviolent resistance during the Vietnam War, he opposed the regime and went into exile in France. Later traveling extensively in France and the United States to propagate his teachings, he wrote over 100 books in English on meditation and mindfulness and exerted major influence on Buddhists and non-Buddhists in Western society.

“Nhat Hanh was probably saying something similar to what I had already been taught, but I got quite a different impression than if I had read a book about Buddhism written in Japanese. It was a revelation to me at the time, that Japanese Buddhism could be approached from the outside. The book got me interested in meditation, and I learned that there is a world in Buddhism that goes beyond words.”

A Global Presence in the Twenty-First Century

Hashimura became chief abbot of Tōdaiji in 2022, when COVID-19 was raging. The temple precincts were deserted; there had probably never been a time when visitors were so sparse. But now that the pandemic has abated, Tōdaiji is once again thronged with people from all corners of the world.

“Some may be concerned about overtourism, but as far as I’m concerned, it’s a wonderful thing to see people from all over the world coming to Tōdaiji. Adherents of many different faiths visit, but here the feeling is tranquil. Meanwhile, religion-based conflicts rage in many parts of the world; once emotions run high, animosity will only grow. In one of the dharma sutras, the Buddha has this to say about the hearts of those who make war: ‘Hate begets hate, and it becomes impossible not to hate. The path forward is to reject hate: that is the eternal truth.’

“Those words were uttered by the Buddha himself, a person who had lost many members of his own family to massacres. Unless we reject hate, the cycle will not be broken. Wars throughout the world occur because of hatred bred when greed and unease collide.”

Buddhism prizes loving kindness, not only for oneself but for others as well, says Hashimura. “Nothing would make me happier than if everyone, regardless of their faith, coming face to face with the Daibutsu, could find it in their hearts to feel even a sliver of compassion for others. Learning about the other faiths of the world besides our own can open the way to understanding others.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview and text by Kondō Hisashi of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Hashimura Kōei at the Tōdaiji Daibutsuden. © Muda Haruhiko.)