Bringing Doraemon to North America: The Challenges of Translating a Classic Manga

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Doraemon, a quirky blue robot cat from the future, is one of Japan’s best known and most loved characters. Originally the creation of legendary manga creator Fujiko F. Fujio, Doraemon made his debut in 1970 in a serialized comic. Since then the cat has been firmly embedded in Japan’s cultural psyche. He has his own TV series, stars in movies, and sells an uncountable range of products. Despite this domestic fame, though, the character has largely stood on the sidelines as Japan’s manga culture advances around the world.

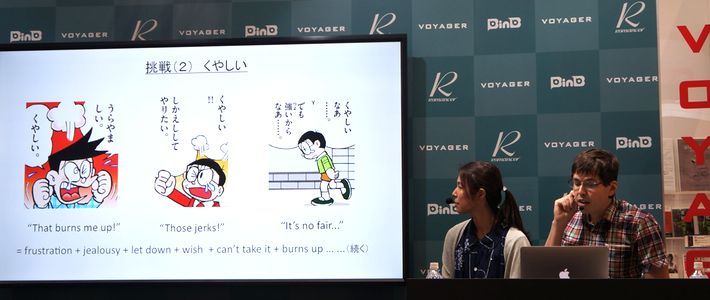

After over 40 years, though, the feline made his long-awaited North American debut in November 2013 when Japan’s Voyager released a digitized English translation of the manga series on the Amazon Bookstore. AltJapan, a Tokyo-based translation and localization company, was charged with rendering the manga into English. Yoda Hiroko and Matt Alt, the husband-and-wife duo that make up AltJapan, gave a presentation this week at the twenty-first Tokyo International Book Fair highlighting the many challenges and hurdles they faced in bringing Doraemon to a wider international audience. In their presentation, the translator pair explained the considerable time and effort involved in finding just the right approaches to preserve the aspects of the manga that have made it such an enduring hit in Japan.

Introducing Doraemon in a New Language

People familiar with the Doraemon comic will know that it revolves around the antics of Nobi Nobita, a wimpy, opportunistic elementary school boy who seems never to be able to do anything right, and Doraemon, a robotic cat who was sent from the twenty-second century by Nobita’s grandson to help his grandfather put his future on the right track. The comic features a diverse cast of other characters. One of the first issues Yoda and Alt had to handle was how to render names.

Although Alt pointed out that the title character’s name doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue in English, giving Doraemon a name more accessible to English readers wasn’t an option. With space constraints to consider, however, the feline is given a nickname, a cultural device familiar to North American readers, and is referred to as “D” in some scenes. Nobita became the more easy to pronounce “Noby,” while Shizuka, the neighborhood heartthrob and focus of Nobita’s prepubescent desires, was deemed easily articulated and kept. Some online grumbling has resulted from Alt Japan’s decision to change the name of neighborhood bully Jaiyan, a Japanese derivative of the English word giant, to Big G. But as Yoda and Alt explain, they wanted to keep the continuity between Jaiyan and his younger sister Jaiko—something that would have been lost in English by naming the character “Giant”—and so the siblings became Big G and Little G.

Key to the Doraemon narrative is the endless variety of gadgets the robot produces from the “fourth-dimensional pocket” on his tummy. These handy knickknacks enable Nobita and other characters to do an endless array of otherwise impossible tasks, like travel through time, enchant objects, and fly. Just as Westerners might ask each other what super power they would choose, Japanese sometimes jokingly discuss which Doraemon gadget they wish they had. Alt chose to go with the word “gadget” as it has a sci-fi ring and gives the impression of something small and useful, but he notes that it may not work perfectly every time.

Where difficulties arose, though, was in the actual choosing of gadget names, which in the comic often have titles rich in wordplay and cultural allusions. For example, one of the best-known devices, a device called hon’yaku konnyaku that lets characters speak and understand other languages when they eat it, plays on the similarities in pronunciation of the Japanese verb for translate, hon’yaku, and a commonly eaten jelly cake, konnyaku, made from a type of yam. Yoda and Alt knew that North American readers would have no idea what many items were and providing a direct translation would fail to express the playfulness inherent in the Japanese—in the case of hon’yaku konnyaku they went with “translation gummy”—and instead often tried to focus on conveying an image of what the devices do. So the dokodemo doa, which allows characters to travel to any destination, became the “anywhere door”; the iconic flying device takekoputa was renamed “hopter,” after hopping and helicopter; and flashlights that change the size of objects, biggu raito and sumōru raito, were christened in science-fiction fashion “magnify ray” and “shrink ray.”

Bridging Linguistic Barriers

One of the more engaging parts of the presentation was Yoda and Alt’s explanation of how they tackled the ubiquitous onomatopoetic words in manga, known as giongo in Japanese, used to represent sound. Shīn, which conveys a sense of silence, was often rendered as “shhh” and gira gira, which connotes something that is sparkling or shiny, became simply “shine.” Yoda noted that sadly, the sense of season that words often convey in Japanese was unable to make the leap to English. One example given was min min, a sound that Japanese readers would immediately recognize as the summer singing of cicadas, but which would be lost on readers in English. In this instance, the two translators went with the sound of singing birds. Yoda and Alt resisted the urge to remove these sounds words altogether, something which has been done when other famous comics were translated into English, as they felt they lent a sense of playfulness that is an integral part of the Japanese comic experience.

The prospect of translating Doraemon, a job that involved rendering over 12,000 pages from Japanese to English, was daunting, but one that the duo at AltJapan seemingly relished. Conveying background and cultural explanations in limited space was not always easy, and finding cultural and linguistic common ground for children’s word games like shiritori, where competitors have to say a word that starts with the ending letter of the last word given, and goroawase, a homophonous wordplay based on numbers and letters, was a mammoth task. When equals were hard to come by, such as when introducing the badminton-like New Year game hanetsuki, they were forced to resort to footnotes. On the whole, though, their emphasis was on finding linguistic matches that allowed the translation to stay as true to the original as space allowed.

For the time being, fans interested in reading the English version of Doraemon will have to purchase it in Canada and the United States. Voyager did not specify when it would be available in other regions, although a company representative did mention that Chinese, Spanish, and Portuguese versions of the comic are also in the works. An English version of the animated series is scheduled to debut in North America later this month on the Disney XD channel.

(Banner photo: AltJapan’s Yoda Hiroko and Matt Alt at the twenty-first Tokyo International Book Fair. © Nippon.com.)

Related Tags

anime manga translation Doraemon Matt Alt Yoda Hiroko localization