Ichirō’s Legend Lives On

Sports World- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Results Win Over the Skeptics

Ichirō’s final Major League game was on March 21, 2019, against the Oakland Athletics at Tokyo Dome. It was the perfect finale. Ichirō (now instructor and special assistant to the chairman for the Seattle Mariners) circled the field in answer to the cheers. As he approached second base, he took off his hat and bade the fans farewell.

Even before the echoes of his retirement faded, though, I saw a social media post by an old acquaintance, an American sportswriter, criticizing the star. The comment was along the lines of how Ichirō has a dark side. He was a great player, but what about as a man? It seemed to doubt if he would ever make it into the Hall of Fame, and the author said he would hold off on casting his own vote for the Mariner when the time came.

Election to the United States National Hall of Fame is decided by a vote. Voting rights are held by reporters who have been members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America for at least 10 years, but that right ends 10 years after the writer retires. I wondered about that writer’s feelings before the 2025 election. Would he be voting or not? I reached out to him before the election announcement, and found out it had been over 10 years since he retired, so he had lost his voting right. When I asked what he would have done if he could, he answered, “I still can’t say I like him as a person. But I suppose I’d give him my vote.” He was an extremely stubborn man, but even he couldn’t help but approve of Ichirō in the end.

Stars of the Past Revived through New Records

Ichirō’s stats are undoubtedly impressive. Jayson Stark, sportswriter for the Athletic, has said “What reason could any voter possibly have to not vote for [Ichirō]?” He not only had over 200 hits a year for a decade running, a Major League record, but he was also a Gold Glove winner ten years in a row. Stark points out that “nobody else even had five seasons in a row like that.”

Ichirō’s Major Records

- 3,089 Major League hits (twenty-fifth in MLB)

- 4,367 total hits in Japanese and American careers (Most in pro baseball)

- 10 years of 200+ hits (first place in MLB), Gold Glove wins, and All-Star games

- Most hits in single season (262 in 2004)

- 2001 season: American League MVP, rookie of the year, leading hitter, stolen base leader

(Compiled by the author.)

Long-time sports columnist for the Seattle Times Larry Stone has covered Ichirō since his 2001 MLB debut. He remarked that no matter how you look at him, Ichirō is a Hall of Fame player. His record breaking 2004 season of 262 hits, he also says, is widely undervalued. He broke George Sisler’s 84-year-old record, which Stone doubts will be broken again anytime soon. No other player has gotten even close yet—another sign of how incredible that record is.

Bob Sherwin, another reporter who has long covered the Mariners, has noted that 200-plus hits for 10 years in a row is likely a more difficult record than 3,000 career hits. The toughest thing in the Major Leagues is long-term, stable play. A 200 hit season is something one person might struggle to do once, he says, but to do it 10 years in a row is unbelievable.

Ichirō hitting his 262nd ball of the season. He broke an 84-year-old MLB record on October 3, 2004. (© Reuters/Andy Clark)

Only two people reached 200 base hits last season. Four people did it in the 2021 season. Luis Arraez of the Padres managed it two years in a row, just squeaking by last season. Ichirō’s 10-year streak broke Willie Keeler’s previous record of eight seasons, from 1894 to 1901. The fact that Ichirō was breaking records that lasted for over a century was another surprise.

In fact, Ichirō’s records served to reawaken interest in the feats of players long gone. In 2016, he achieved 10 hits in 13 at-bats in three games from May 21. As a player 42 years old or older, this record broke one that was 122 years old, set by Cap Anson of the Chicago Colts (now the Cubs) in August 1894. That also helped point out how Anson was the first MLB player to get 3,000 hits, but that was in an era when walks were counted as hits.

Changing the Emphasis on Power

When Ichirō had his Major League debut, the focus was on big players smashing home runs. This also encouraged the spread of steroids, encouraging the league to come down on the practice. A player strike from 1994 to 1995 drove fans away, but the home run power hitting of players like Mark McGwire of the Cardinals and Sammy Sosa of the Cubs helped bring them back.

They were days when second-base grounders that turned into safe infield hits were simply unthinkable. But when Ichirō’s hits rolled toward the shortstop, the fans were on their feet in anticipation. He was also a player who gave serious thought to base running and defense. In that era, the players sent out to left and right field tended to be counted on mainly for long balls at the plate, and their defensive performance was an afterthought. But when Ichirō was in the outfield, he could take out hitters aiming for an extra base or two with his trademark “laser beam” throws to third, thrilling fans.

Clark Spencer, who covered Ichirō for the Miami Herald during his Marlins days, says that Ichirō reminded him of watching players like Pete Rose when he was a kid. He has the highest praise for Ichirō’s baseball IQ, stating that he’s never seen him make a boneheaded play, even though every player has one or two. He knows everything about baseball, says Spencer, reminding fans of both the joy and the difficulty of the sport.

Overcoming the Rumors

What was it that has helped Ichirō reach so far? On July 30, 2008, in an interview after he hit a total of 3,000 hits in his Japanese and US careers, he answered that question like this: “I learn a lot by watching people. When you watch how people act, there are lots of things that stand out. I think I am the way I am now by taking those points and using them myself.”

But the public reaction to his drive to accumulate of records was not always positive. Breaking records became a way to maintain motivation as he played out seasons with a losing team. But that became a sticking point with those around him, who could be heard expressing the sentiment that “Ichirō is only interested in his own records.”

Naturally, that weighed on him. In a 2008 interview, he said: “The negative atmosphere seeps in through my skin. When you’re on a losing team, there are people who try to hold you back. I am thinking about how to not be held back. The only way is to get results.” He even went so far as to ask teams to stop announcing new records on scoreboards when they happened.

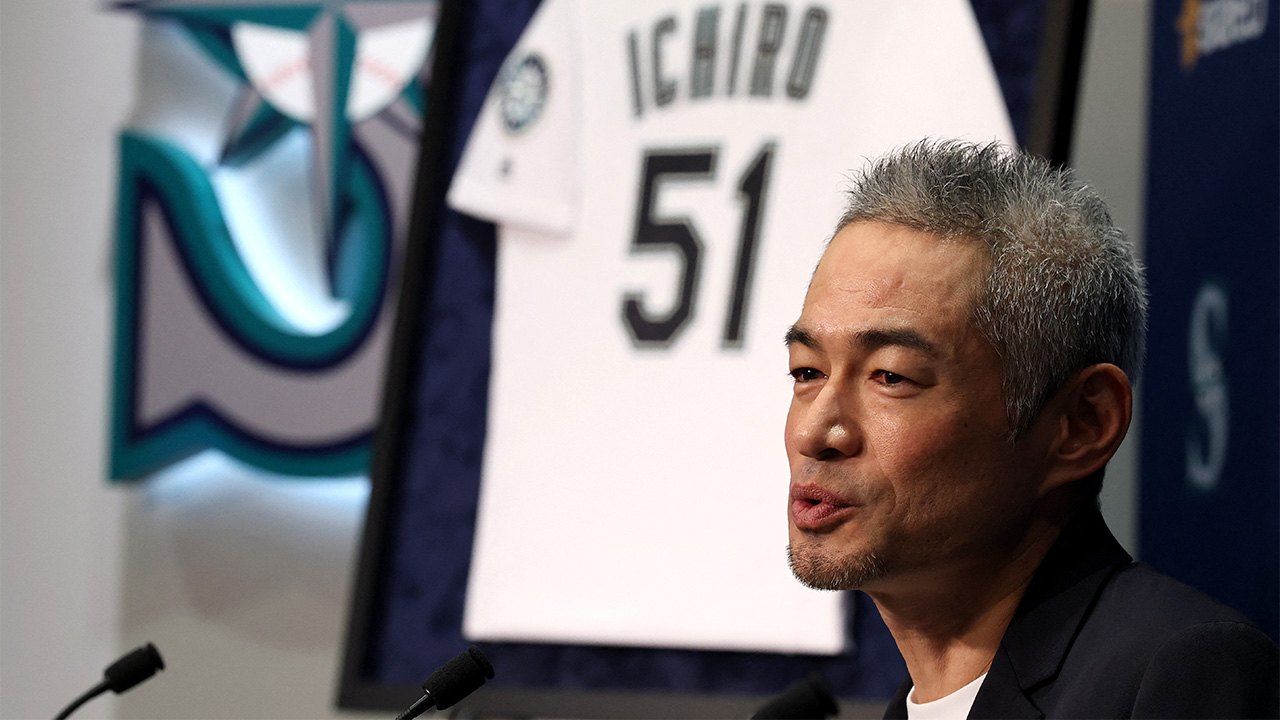

When he achieved his tenth year in a row of 200 hits, though, his teammates celebrated it, and that seems to have broken some ice for him. “It felt all right to be happy about it. Because the rumors had been so traumatic.” Then, in 2025, came the January 21 press conference about his Hall of Fame election. He was welcomed with a chant of “I! Chi! Rō!” by Seattle Mariners team staff. The packed venue saw members of the media mixing with former teammates like John Olerud and former Mariners President Chuck Armstrong. Receiving such congratulations from people he had known so long, Ichirō showed the brilliant smile of someone who has overcome tougher times in the past.

A New Path as a Baseball Lover

Now, Ichirō is working up a sweat during the seasons as an instructor for young Mariners players. In Japan, he also instructs high school baseball and promotes the popularity of girls’ baseball. Now that he’s moved on from playing, how does he see the game?

Ichirō has said he feels a sense of danger in MLB’s overreliance on data. In 2015, the league’s own data analysis tool called Statcast appeared. This now offers numerical stats to represent hard-to-see factors, such as batter swing speed, initial speed of hit balls, and hit angles. For pitchers, it analyzes ball spin and the influence of seams on the ball.

In a July 2017 interview, Ichirō had this to say on the data-based approach to the sport. “Data on things like swing speed or ball speed is fundamentally useless. This is something that the players understand.” Should players work to boost these detailed stats? Would that enough to be able to get them more base hits? There’s no denying that the fans enjoy exploring the numbers here, but there are arguments against using them to rank players, says Ichirō.

“With two outs and someone on third, dialing down the power to drop a fast ball just behind the shortstop is a great technique to have in your batter’s toolchest. But according to current Major League values, putting all your power into a ball hit straight down the center is seen somehow as better than getting another run. It’s idiotic. I’m worried that baseball is going to become a competition without thought.”

Ichirō is speaking here about the way that data is used. Focusing on data is putting the cart before the horse. As he puts it, “Just swinging faster is something anyone can do without thinking.”

If Ichirō had made his Major League debut today, what kind of player would he be? There’s no doubt he would be setting standards for batters, like pitching pioneer Trevor Bauer, who has used data more than anyone. That is exactly why I would like to see Ichirō demonstrating the right way to use data as an instructor. How will he bring the data and those things that cannot be measured with numbers together? The answer to that is sure to be a new achievement for the history books by a true baseball man.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Ichirō at a press conference after his election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame on January 21, 2025, in Seattle. © AFP/Jiji.)