Feeding the Nation: How Japan’s School Lunches Changed Through the Twentieth Century

Society Food and Drink Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The First School Lunch

Japan’s first school lunch is said to have been served in 1889 at a school at the temple Daitokuji in what is now Tsuruoka, Yamagata Prefecture, which was established by priests for children who were too poor to attend other schools. The free lunch consisted of salted rice balls, salted salmon, and pickled greens, and was paid for with alms collected by the priests.

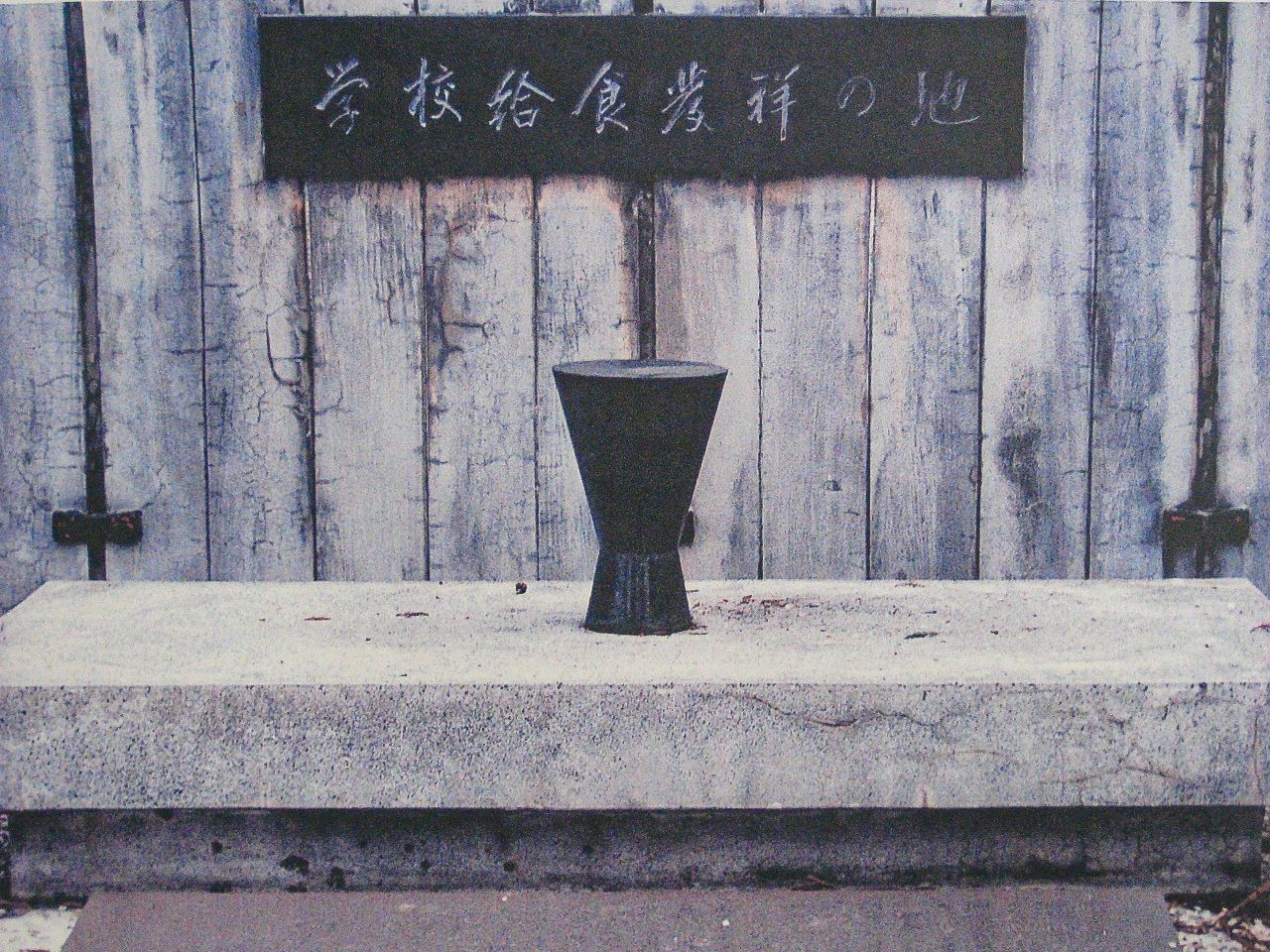

A monument to Japan’s first school lunches in Tsuruoka, Yamagata. (© School Lunch History Museum)

Tsuruoka was the castle town of the former Shōnai domain, where there were strong local ties and a spirit of mutual aid. This location also had a rich food culture, providing the rice and salmon for the meal, which came together neatly with the benevolence of the priests. From the beginning, the ideal of supporting poor children without allowing them to feel a sense of inferiority has underpinned school lunches in Japan.

A re-creation of the first school lunch with salted rice balls, salted salmon, and pickled greens. (© Japan Sport Council)

Similar initiatives followed in other areas, paid for by local governments or through donations from the wealthy, while disasters like the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake and major famines in Tōhoku through the 1930s led to the expansion of lunches for children without food. During the 1930s, the national government established policies for providing school lunches.

As Japan ramped up its invasion of China and its society became increasingly war-oriented, apart from providing food to children who lacked it, the government encouraged school lunches as a way of improving children’s nutrition and physical condition. However, wartime shortages as Japan neared its eventual defeat led to most schools halting their programs. Food shortages during and after the war caused severe malnutrition, and children were physically weaker than their prewar peers. A postwar survey by the Tokyo government found that 40% of children hardly ate at all each day and another 40% only had one meal.

A Timeline for Japan’s School Lunches

1889 First school lunch in Tsuruoka, Yamagata

1923 Great Kantō Earthquake

Wartime School lunch programs halted in later stages of World War II

1945 End of World War II

From 1946 With the assistance of the United States and others, bread and powdered skimmed milk provided for school lunches

1949 UNICEF launches support for school lunch programs

1950 US Government and Relief in Occupied Areas program supports school lunch programs

1951 GARIOA support discontinued as Japan regains sovereignty

1954 School Lunch Program Act enacted

1960s Shift from use of powdered milk to fresh milk

1976 Official introduction of rice as part of lunch

2005 Enactment of Food and Nutrition Education Act

2008 Amendment of School Lunch Program Act to stipulate the importance of food and nutrition education

Created by Nippon.com based on information from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology and other sources.

Food and Education

After the end of World War II, the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, which ran occupied Japan, grew concerned that the country’s food crisis would lead to social unrest. At the order of US President Harry Truman, a delegation led by former President Herbert Hoover arrived in Japan and called on GHQ leader General Douglas MacArthur to restart school lunches, insisting on the necessity of importing food.

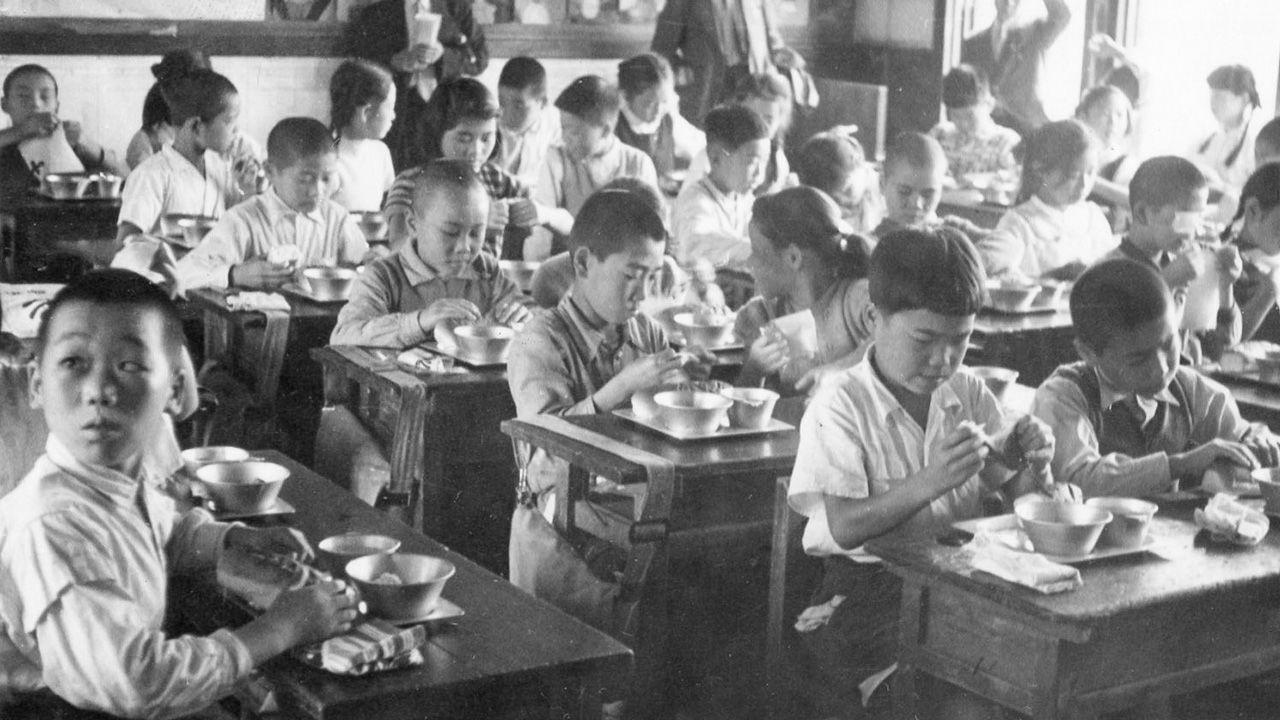

With the backing of GHQ, on Christmas Eve 1946, school lunches began for 250,000 children in the prefectures of Tokyo, Kanagawa, and Chiba. The program was based on a donation from the grouping of American private charitable organizations Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia. Truman is said to have added the word “licensed” to indicate full presidential approval and American support for this program.

A re-creation of the first postwar school lunch, consisting of tomato stew and reconstituted powdered milk. (© Japan Sport Council)

The first standard school lunch included only tomato stew and powdered skim milk, but it was a valuable source of nutrition for children who did not always know when they would receive their next meal. Support in the form of goods from overseas remained important, and as part of US occupation policy, further help came through the Government and Relief in Occupied Areas fund. In 1950, full meals with bread, milk, and side dishes were provided twice a week to 1.3 million elementary schoolchildren in Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, Kyoto, Osaka, Kobe, Hiroshima, and Fukuoka.

However, when Japan regained its sovereignty after the San Francisco Peace Treaty was signed in 1951, the GARIOA funding came to an end. The payment burden fell on families, leading to a national campaign to reinstate school lunches paid for by the government. In 1952, the government began subsidizing half the price of flour, and complete school lunches spread throughout the country.

In 1946, the three vice-ministers responsible for education, health, and agriculture published a directive on the policy of promoting the adoption of school lunch programs to support children’s health and development. This described their educational effects in 10 categories from knowledge about hygiene and nutrition to etiquette and the spread of democratic thinking.

The School Lunch Program Act was enacted in 1954. It formalized the repositioning of school lunches from simply providing nutrition to their role as a part of children’s education, and by instituting a legal framework, it led to a unique path of development within Japan, even while the country continued to rely on foreign food imports. The act’s four basic goals were as follows:

- To cultivate an understanding of the role of food in daily life, as well as good habits

- To enrich school life and foster cheerful social interaction

- To institute regular dietary habits among children and improve nutrition and health

- To provide guidance toward an understanding of food production, distribution, and consumption

These four points and the educational benefits described in the vice-ministers’ directive are still valid today.

Key Foods in Japan’s School Lunches

The next section looks at some of the major foods associated with school lunch in Japan, and the background to their appearance on the menu.

Deep-Fried Whale

Most Japanese people over 50 have eaten whale, which made its first appearance in school lunches around 1950. At that time, Japan was a major whaling nation, and whale meat was seen as a valuable source of protein. At one-third the price of pork, it featured regularly in school lunches until around 1980.

A re-creation of a 1952 school lunch with a bread roll, made-up powdered milk, and deep-fried whale. (© Japan Sport Council)

Agepan

These deep-fried bread rolls coated with kinako soybean flour and sugar are a favorite with all generations. Once, if children were sick, friends who lived nearby would deliver some of their school lunch, including bread. A school cook in Tokyo got thinking about what he could do to keep the bread tasty and stop it from going hard, and invented the agepan in 1952. The sweet bread had a stunning impact and became part of the menu nationwide in the early 1960s. It is still popular today and can also be purchased in many convenience stores and supermarkets as a ready-made snack.

Milk

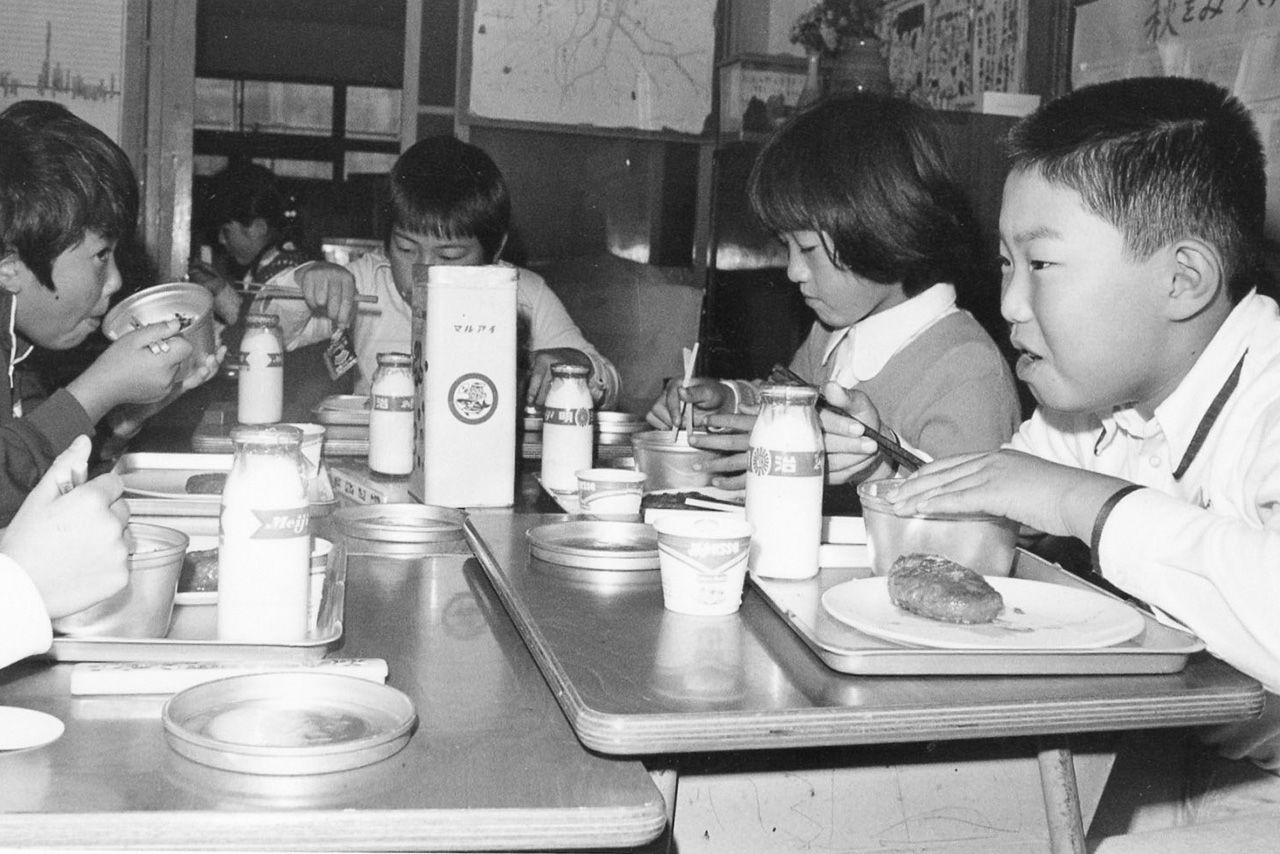

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, skim milk made from powder was served in school to provide children with nutrition. It did not dissolve well, often burned when heated in a pan, and gave off a distinctive odor after it cooled that many children disliked. Eventually, a system to supply domestically produced milk was established, and following a 1964 directive, schools progressively made the switch from powdered to fresh milk.

Soft Noodles

The school lunch staple popularly known as sofuto men (soft noodles) came in individual plastic packs, which were transferred to dishes and served with curry sauce or meat sauce. These noodles were first produced around 1960 by a Yokohama manufacturer in response to calls within the industry to include the food in school lunches. To overcome the shortcoming of noodles going soggy when they were cooked too long, it used hard bread flour and a special method of steaming noodles and soaking them in cold water before boiling. With the emergence of udon and Chinese noodles (Chūka men) made with special flour, soft noodles largely disappeared from the menu.

A re-creation of a 1965 school lunch including bottled milk and soft noodles. (© Japan Sport Council)

Rice

Today, it goes without saying that rice is a part of school lunches in Japan, but this only became the case more than 30 years after the end of World War II. In the immediate postwar years, rice crop failures prevented making the grain a standard part of meals. From 1965, while there were improvements in rice production technology, the high-paced growth of the economy led to the Westernization of diets and large rice surpluses. As a way to use these up, the use of rice in school lunches was debated and then adopted formally nationwide from 1976. At first, bread remained the main staple in many schools, but with the introduction of increased discounts for school lunch usage in 1979, rice spread to become a new standard.

Elementary school students eating lunches including rice in Mashiko, Tochigi, in 1978. (© Japan Sport Council)

With the introduction of rice in lunches, cooking it was outsourced to bread factories. Photograph from 1978. (© Japan Sport Council)

At the same time, while many schools were serving rice at school lunches in the 1980s, family restaurants caught on and Western food became more prevalent both in homes and when eating out. Reflecting this, in 1983 the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries advocated a Japanese-style diet, which would combine rice as a staple with side dishes influenced by other countries, while maintaining the traditional food culture. School lunches consequently became more diverse.

(Originally published in Japanese on January 24, 2025. Banner photo: Elementary school students enjoying lunch together in 1952. © Japan Sport Council.)