Art in the Rice Paddies: Festivals Bring Energy and Investment to Japan’s Countryside

Art Culture Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Bringing the Power of Art to Rural Okayama

The Forest Festival of the Arts Okayama, which came to an end on November 24, 2024, was the latest international art festival to bring cutting-edge contemporary art to a rural area of Japan. Held over 58 days, the festival encompassed venues across 12 municipalities in the northern part of Okayama Prefecture—mostly in and around the small towns of Tsuyama, Niimi, and Nagi—surrounded by the fields and natural landscapes of a predominantly agricultural part of the prefecture, far from the heavily populated areas along the coast. Although this was the first time the festival had been held, the organizers put together an impressive line-up, drawing well-known international artists such as Ernesto Neto from Brazil and Kimsooja from Korea, as well as major names on the Japanese arts scene, including the photographer and filmmaker Ninagawa Mika, the architect Sejima Kazuyo, and the photographer Kawauchi Rinko. Other highlights included a collaboration between the composer Sakamoto Ryūichi and Takatani Shirō of the art collective Dumb Type, completed not long before Sakamoto’s untimely death in 2023.

Many municipalities in the north of Okayama are struggling with the problems that increasingly affect many rural parts of Japan: isolation, lack of economic opportunities, and dwindling, mostly elderly populations. There is now a stark economic gap between the north of the prefecture and the coastal cities of Okayama and Kurashiki, where most of the industry, jobs, and population are concentrated.

The Forest Festival was born from the idea of using art to promote the region and address the growing north-south divide. Local governments worked with the festival’s organizing committee to attract visitors to this remote area, putting on special festival bus tours departing from the main stations in Okayama and Tsuyama, increasing the number of services on local railways and bus routes, and lobbying travel agents to design special tour packages around the festival.

During the Forest Festival, Leandro Erlich’s “Nature Above” brought a touch of the surreal to an indoor facility normally used by elderly locals for their gateball games. Taken in Nagi, Okayama Prefecture, on September 27, 2024. (© Morita Mutsumi)

Argentina-born artist Leandro Erlich, whose “Swimming Pool” is one of the highlights of the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, created a new installation for the festival using fake trees suspended upside down from the ceiling and reflected in a “lake” of mirrors in the floor. The artist said he was inspired by Okayama’s rich natural landscapes. Visitors cross a bridge through the middle of the temporary exhibition space, surrounded by lush greenery. Despite being in an indoor center for gateball—a croquetlike game commonly played by Japan’s senior citizens—it feels as though you’re walking through the depths of a forest. When you look down, you see the reflected trees swaying gently in the breeze. It’s a disconcerting sensation: you’d swear you were crossing a real bridge over a real lake. The piece is typical of Erlich’s work, which often uses immersive installations to create illusions that upset “commonsense” assumptions about how we perceive the world around us.

Chien-Chung Liao from Taiwan also foregrounded nature in “Echoes in the Mountains,” his giant open-air sculpture of a crested kingfisher, a bird native to northern Okayama. Some 6.5 meters tall, the piece is made from thin metal slats, allowing light and air to pass through. At the heart of the sculpture grows a Japanese magnolia, emphasizing the close connections between manmade art and the natural environment.

Chien-Chung Liao stands in front of “Echoes in the Mountains,” built for the Forest Festival of the Arts. September 28, 2024, Kagamino, Okayama. (© Morita Mutsumi)

Ninagawa Mika and her creative team used the Makidō limestone cave in Niimi as the setting for a collaborative piece. The cave has been used several times as a location for movies and TV dramas, notably for the film Yatsuhaka-mura (The Village of Eight Graves), based on the novel by Yokomizo Seishi and featuring the fictional detective Kindaichi Kōsuke. Ninagawa strewed the floor of the cave with artificial spider lilies, creating an eerie, otherworldly landscape. (In Japanese, the name of the flower is higan-bana, or the “autumn equinox bloom,” and the flower has associations with gravesites and the afterlife.) Many other unique and original works by participating artists studded the natural landscapes throughout the festival, turning these small towns and the fields around them into colorful canvases of contemporary art. The festival also promoted the local food, selling festival bento boxes made from locally sourced ingredients and specially made bread snacks designed to resemble the famous local peaches.

The festival attracted more than 520,000 visitors. Acting as art director for the festival was Hasegawa Yūko, director of the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, and honorary professor of curatorial and art theory at Tokyo University of the Arts. Hasegawa believes art festivals like this can play a crucial role in highlighting the untapped potential of Japan’s neglected rural regions: “The setting here is one with huge potential. The area is largely unaffected by earthquakes and has lots of underutilized resources. Art and artists can help by putting their finger on what makes a place unique and turning that narrative into something tangible that other people can see.”

Festival art director Hasegawa Yuko (left) and artist Leandro Erlich (right) relax on a bench designed by the architect Sejima Kazuyo (center). September 28, 2024, Maniwa, Okayama Prefecture. (© Morita Mutsumi)

Niigata’s Pioneering “Art Field” Festival

Globally, the best-known art festivals include the Venice Biennale (first held in 1895), the Documenta festival, held every five years in Kassel, Germany (first held in 1955), and the Saõ Paulo Biennale in Brazil (first held in 1951). In Japan, the trailblazer in terms of bringing art to areas beyond the major cities was the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, which has been held in the Tsumari district of rural Niigata since 2000. The area, which receives some of the heaviest snowfall of anywhere in Japan, faces the familiar problems of an ageing and declining population, compounded by a lack of economic opportunities. The local government came up with the idea of using art to attract visitors in the hope that a festival would infuse new life into local communities and promote exchanges between this isolated region and the outside world.

“Ephemeral Bubble” by Ma Yansong, one of the artworks at the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, in which a traditional house seems to be blowing bubble gum. July 12, 2024, Tōkamachi, Niigata Prefecture. (© Morita Mutsumi)

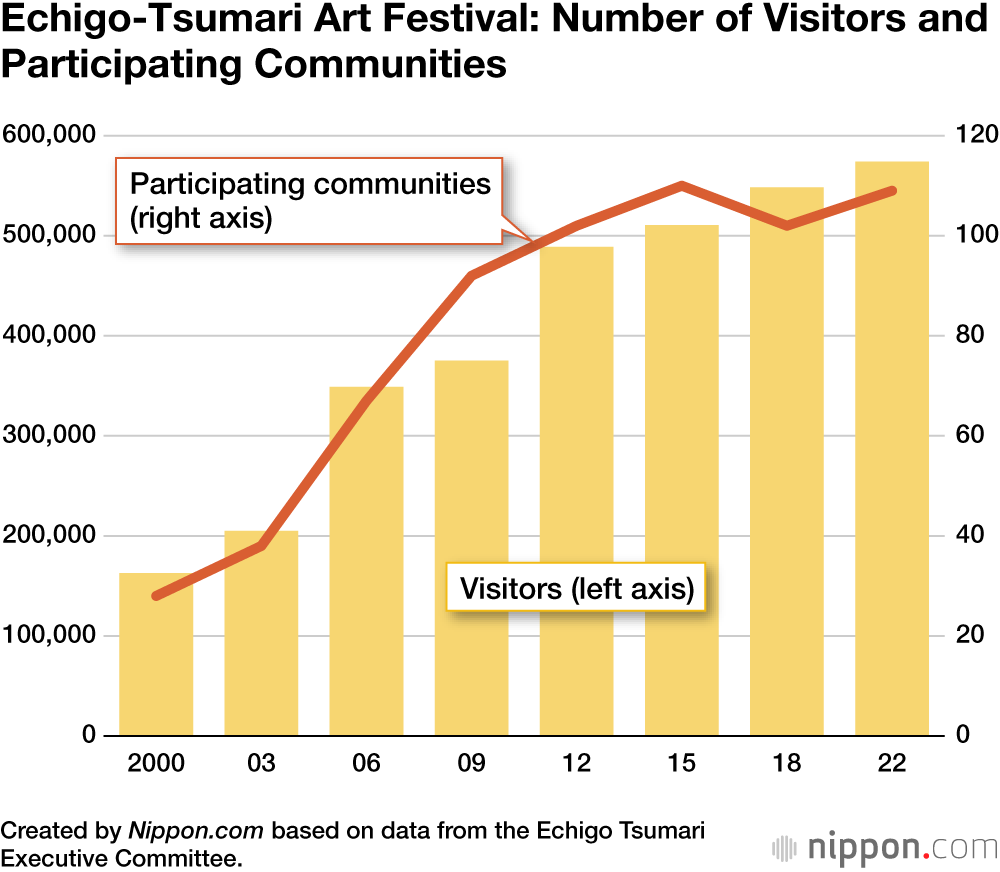

The festival presented a new concept. As well as enjoying the art, visitors would also take in the natural landscapes of the region and experience its culture and food. The idea has resonated with the public, and visitor numbers have increased with every new edition of the festival. The first edition in 2000 drew 162,800. By the time its eighth outing was held in 2022, this number had risen to 574,138.

The success of the Niigata’s Echigo-Tsumari Art Field inspired a succession of similar festivals around the country in the years that followed, including the Sapporo International Art Festival, Yamagata Biennale, the Reborn Art Festival (Miyagi Prefecture), the Nakanojō Biennale (Gunma Prefecture), the Saitama International Art Festival, the Oku-Noto International Art Festival (Ishikawa Prefecture), the Okayama Art Summit, and the Yambaru Art Festival (Okinawa).

Naoshima: Glittering Success Story in the Inland Sea

Of all the art festivals organized with the aim of revitalizing local communities, perhaps the biggest success story has been the Setouchi Triennale, held every three years on a growing number of islands in the Inland Sea between Honshū and Shikoku. The festival was first held in 2010, on the initiative of a team led by Fukutake Sōichirō (honorary chairman and advisor at Benesse Holdings). The islands are now home to a proud legacy of boldly original artworks by leading international artists including James Turrell (United States), Christian Boltanski (France), and Olafur Eliasson (Denmark/Iceland), as well as both established and up-and-coming figures from the Japanese art scene, including Kusama Yayoi, Yokoo Tadanori, Sugimoto Hiroshi, Naitō Rei, and Nawa Kōhei. Several of the islands now boast impressive buildings by famous Japanese architects including Andō Tadao, the creators at the firm SANAA, and Sanbuichi Hiroshi, and have become popular attractions even outside festival time.

Kusama Yayoi’s “Red Pumpkin” is on permanent display at Naoshima, and has become a symbol of the “art island” in the Inland Sea. September 28, 2010, Naoshima, Kagawa Prefecture. (© Morita Mutsumi)

Several impressive buildings have been added alongside the initial group of artworks, including the Lee Ufan Museum and the Teshima Museum of Art, and many of the works created for the festival in earlier years can now be seen on a permanent basis. Even outside the festival period, Naoshima and the surrounding islands have become a popular pilgrimage spot for art-lovers, with Naoshima in particular now regarded as a “must-see” destination by many overseas visitors. Gallery staff members who show international visitors around Japan when they come here for exhibitions and other art-related events tell me that these visitors want to include Naoshima on their itineraries “almost without exception.”

Ōtake Shinrō’s “I Love Yu” bathhouse offers visitors a unique opportunity to truly immerse themselves in art. Built in 2009, the public bathhouse is still in operation today, and is more popular than ever. Naoshima, Kagawa Prefecture. (© Morita Mutsumi)

Large numbers of foreign tourists visited the Setouchi Triennale in 2016. The white frisbee in the center of this photo is the roof of the remarkable Teshima Art Museum, designed to blend in with the terraced rice paddies of the surrounding countryside. Tonoshō, Kagawa Prefecture. (© Jiji)

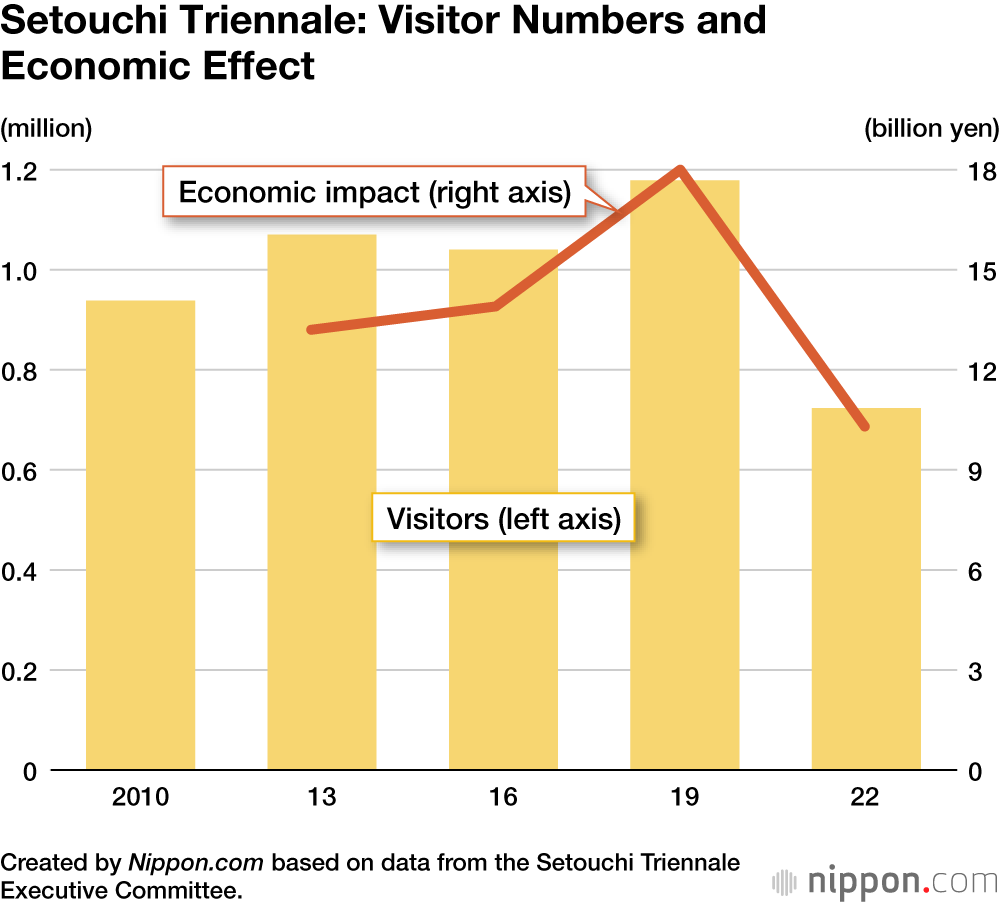

According to information published by the festival’s organizing committee, more than a million people visited the 2019 edition of the festival, before COVID-19 hit, bringing economic benefits worth some ¥18 billion yen. Even in 2022, the festival brought ¥10.3 billion to the local economy, despite the lingering impact of the pandemic.

For many struggling municipalities in rural parts of the country, success stories like these are a beacon of hope, and more and more local governments are interested in the potential of art festivals to open up new possibilities for regions in decline. One example is Suzu in Ishikawa Prefecture, at the tip of the Noto Peninsula.

Before the advent of the railways, the town prospered thanks to its position on the route of the kitamae-bune ships that plied the Japan Sea coast, carrying goods from Osaka to northern Honshū and Hokkaidō. It was also home to a fishing industry, salt production, and a number of ceramics kilns. But in recent decades, the population has fallen dramatically, from a peak of around 38,000 people in 1950 to around 10,000 today. For a while, there were rumors that a nuclear power plant would bring jobs to the town. Another idea was to bid for the right to host a casino, but neither of these schemes to attract new investment came to fruition. Eventually, the local government came up with the idea of the Oku-Noto International Art Festival. The festival was held for the first time in 2017, then again in 2020 and 2023. But the major earthquake that struck the Noto Peninsula on New Year’s Day, 2024, damaged several of the main venues, and at the moment there are no firm plans for when the next edition of the festival might be held. Despite this setback, the human connections built through art continue to provide a glimmer of encouragement as well as a sense of connection with the wider world.

Given success stories like Echigo-Tsumari and Setouchi, it is not surprising that many local governments around the country see art festivals as their best bet for injecting much-needed vitality into their regions. Kitagawa Fram (chairperson of Art Front Gallery) acts as overall director and advisor for a number of festivals, including the Echigo-Tsumari Arts Festival, the Setouchi Triennale, the Northern Alps Art Festival in Nagano Prefecture, and the Oku-Noto Arts Festival in Ishikawa Prefecture. He regularly fields inquiries from local governments all over Japan, not to mention China and Taiwan, about the possibility of hosting art events—“easily more than 100” in the past few years, he says. This extraordinary number gives an idea of how invested many local governments have become in the idea of art as a way of regenerating the local economy and attracting tourism to their regions.

The Importance of Local Investment

But results do not come overnight—if they come at all. The understanding and cooperation of local people is essential to any art festival. From the perspective of elderly people with little previous exposure to contemporary art, however, it can be hard at first to find much merit or meaning in the art on offer. Not surprisingly, there are often objections and opposition to the idea of holding an art festival. In the runup to the first Echigo-Tsumari festival, Kitagawa says he traveled to the region on an almost daily basis. He and local government officials held more than 2000 meetings over a period of four and a half years to explain the festival and its objectives to local people and ask for their understanding and support. Initially, though, even after it was agreed that the festival would go ahead, few local people put themselves forward as volunteers. The anticipated crowds failed to materialize, and people made fun of the tour buses he had laid on, joking that they were carrying nothing but fresh air.

Over time, though, as the festival went through several editions, local people grew used to the ways of the art world, and gradually became more willing to help. Artists too started to feel affection for Echigo-Tsumari and became accepted by the local communities. The fruits of these exchanges can be seen at venues around the Echigo-Tsumari Art Field today. When I visited in July 2024, during the ninth iteration of the festival, I was struck by the sight of local people proudly explaining the artworks on display around the site.

If there is determination in a local community to make a festival a success, it will feed off this enthusiasm and visitor numbers will steadily increase. This creates more momentum, leading to a virtuous cycle. On my recent visit I saw for myself how the increasing number of artworks left on permanent display after the festival is over, as well as the museums and other facilities, are making a lasting contribution to the local infrastructure, and how art has put down roots in the local community.

The Kiyotsu Gorge Tunnel has become a major tourist draw since it was converted into an artwork known as the “Tunnel of Light” for the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in 2018. July 13, 2024, Tōkamachi, Niigata Prefecture. (© Morita Mutsumi)

Keeping the Message Alive After the Festival Is Over

Okayama’s governor, Ibaragi Ryūta, served as chair of the organizing committee for the Forest Festival. He admits: “It’s not a region with particularly good transportation links, but I thought l there was a chance we could make it a success.” He says the example of the Setouchi Triennale, where visitors are ferried between the different islands by boat, encouraged him to think that a festival might be feasible even in a relatively remote part of the countryside. Even so, he shies away from any firm comment on prospects for the future. Will the festival be held again? “We will look at visitor numbers and see how the festival was received and what impact it had on local communities, and then make an overall decision based on all those factors,” he says.

The opening ceremony for the Forest Festival of the Arts Okayama. Fourth from left is Prefectural Governor Ibaragi Ryūta. Tsuyama, Okayama Prefecture. (© Morita Mutsumi)

It wouldn’t be the first festival that has failed to last the course. Take the Kenpoku Art festival, held in northern Ibaraki in 2016. This was held just once before its budget was cut when the local government decided there was not enough evidence that it would contribute effectively to the sustainable development of the region in the long term. A change of governor was apparently one of the factors in the decision.

The Water and Land Niigata Art Festival, which was held every three years in the city of Niigata from 2009, also came to an end in 2018, after four editions. The city’s mayor was apparently eager to continue with the festival, but other members of the city council were skeptical about cost effectiveness at a time when municipal finances were increasingly strained. When a new mayor took over, the decision was taken to pull the plug.

Art festivals are not a panacea that will instantly solve a region’s economic woes. Nor should they become fleeting spectacles like a fireworks display, providing a brief flash of color before fading to darkness again. The challenge for organizers is to ensure that the energy and benefits of a festival do not simply dissipate once the event is over. As art festivals continue to spring up across the country, a key challenge will be to create the kind of sustained community engagement and long-term impact that are crucial to a festival’s prospects of success.

Can the local community be inspired to nurture the festival together with the organizers and local government? To what extent can local people be persuaded to invest in the festival and regard it as something that truly belongs to the community? The answers to these questions will determine which of these many festivals go on to become lasting institutions—and which quickly fade into memory, like fireworks on a summer’s night.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: An installation by Ninagawa Mika and her collaborators created an otherworldly landscape scenery in which countless spider lilies seem to burst into bloom inside the darkness of a cave. September 29, 2024, Niimi, Okayama Prefecture. © Morita Mutsumi.)