“Quality of Life” in Japanese Evacuation Shelters: Learning from the Taiwan Experience

Disaster Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Long Wait for Comfortable Beds

When the Noto Peninsula earthquake struck on New Year’s Day, 2024, we saw evacuees taking shelter in school gymnasiums and community centers, lying on cold, hard floors. There were no partitions to separate people who were essentially forced to huddle together. This was not a remarkable scene in Japan, however: Similar problems were witnessed following the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake.

In the Ishikawa Prefecture town of Noto, 5,481 people were forced to take refuge in designated evacuation shelters, mainly school gymnasiums with hardwood floors. However, the decision to roll out more comfortable cardboard beds on a broad scale was not made until January 10, more than a week after the earthquake. The actual introduction of these beds took until January 16—the third week following the disaster. Influenza and COVID-19 infections also began to spread throughout evacuation shelters. As bad as this was, it was still the swiftest response in the wider Noto Peninsula disaster area, as other municipalities were even slower.

The Japanese government drew up operational guidelines for evacuation shelters in 2016 based on experiences from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. The guidelines specified the use of cardboard beds separated by partitions, rather than people sleeping together in a huddle. This would have multiple effects, including a reduced likelihood of “economy class” syndrome triggered by lengthy times spend in seated or cramped positions, less exposure to cold air and dust from hard floors, and mitigated spread of infectious diseases. The aftermath of the Noto Peninsula earthquake demonstrated clearly that this was not always possible.

Chaotic Shelter Planning and Unused Supplies

A report compiled by a government-appointed team tasked with independently investigating the Noto Peninsula disaster response noted several issues:

- When shelters were opened to accept evacuees, the layouts of the living spaces had not been determined in advance

- Sleeping areas were often not partitioned

- Cardboard beds were often unavailable, or not set up even when on hand

- People entered shelters with shoes on, alongside other insufficient hygienic and anti-infection measures

Further issues related to the central government’s “push-type” material support operations were also noted. “Push-type” support is aimed at delivering aid supplies to disaster-hit areas without waiting for specific requests, based on the assumption that local municipalities are likely unable to function properly or adequately convey the situation. In the case of the Noto Peninsula earthquake, 3,200 partitions and 7,000 cardboard beds were proactively provided to disaster areas, but many went unused despite clear need. Items of varying sizes and durability were also available, but which items would be delivered to which locale was not considered in advance. This forced people on the ground to make decisions about appropriate use based on what was sent to them.

Distribution Problems Hamper Relief

“Push-type” support operations began on January 2, the day after the disaster, when the government and other support groups began sending relief supplies, including food, fuel and daily necessities. However, the independent report described several cases of food and other essential supply shortages being experienced at evacuation centers. The January 3 online edition of the Yomiuri Shimbun reported Wajima Mayor Sakaguchi Shigeru appealing for even more help, quoting him at a meeting saying: “We have only received 2,000 meals for 10,000 evacuees; we are seriously short of water and food.”

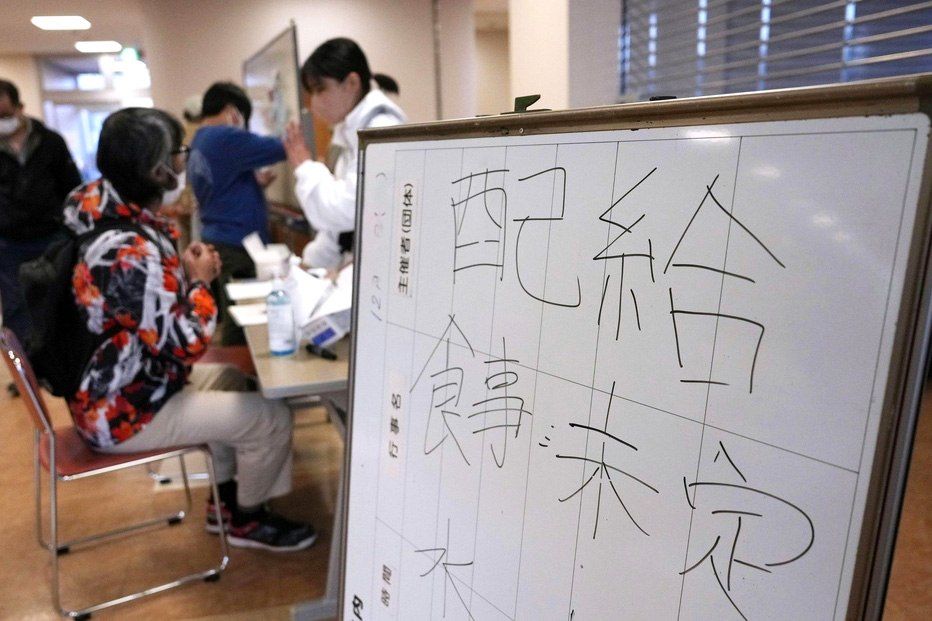

A bulletin board at an earthquake shelter in Wajima, Ishikawa Prefecture, informs people that “food and water distribution has yet to be determined.” January 2, 2024. (© Kyōdō)

One of the hardest hit areas was at the tip of the Noto Peninsula. Compounding matters for this area was the damage to the Noto Satoyama Kaidō expressway. This road spans the entire peninsula from south to north and connects the region to the prefectural capital, Kanazawa. With transport routes severed, supply and relief operations ground to a halt. The Self-Defense Forces were initially forced to use helicopters and other less efficient means to transport the large quantities of essential goods.

Confusion during the distribution process, as well as a lack of training and awareness of the response system, also contributed to supply bottlenecks. The independent report describes how the Ishikawa Industrial Exhibition Hall in Kanazawa became the base of operations for gathering supplies from around the country and then distributing them to the afflicted areas. However, because the supplies were not arranged on pallets, forklifts could not be used, resulting in a time-consuming hand-loading process. Distribution management was also initially carried out using analog methods such as officials taking photos of handwritten lists and sharing them by email. An online and digitalized distribution management system that allowed needs assessment and inventory tracking did not begin operation until January 5, despite advanced plans for using such a system.

This is all despite a large earthquake having already struck the Noto Peninsula region in 2007. At the time there was widespread recognition that surviving in shelters while supplies were cut off was likely going to be a future challenge. Amtd the chaos and confusion, it seems that the lessons of 2007 were difficult to fully implement in real time.

Taiwan: High Quality Shelters Up and Running in Hours

The Noto earthquake response effort can be usefully compared with the response to a 7.4-magnitude earthquake that struck the east coast of Taiwan on April 3, 2024. Killing 18 people and injuring more than 1,100, the earthquake’s epicenter was in Hualien County.

The Hualien County government was quick to respond. Within an hour of the earthquake, a network of government and civil society contacts was up and running using the Line messaging app. Evacuation shelters were immediately opened, and two hours after the earthquake, community organizations were setting up and making available tentlike partitions at evacuation shelters that provided ample privacy and separation.

People resting at a temporary shelter at an elementary school following the Hualien earthquake in Taiwan. The shelter was quickly set up using tentlike partitions to protect people’s privacy. (© AFP).

Furthermore, the evacuation centers were air-conditioned, and hot meals were available. The shelters also had administrative support desks, free wireless internet, smartphone charging facilities, free aromatherapy massages, and free dry-cleaning services. Game consoles were also available in the children’s play areas.

One of the civil society organizations working to improve conditions at Taiwan’s evacuation centers is the Buddhist Tzu Chi Charity Foundation. This is an international NGO that has a team of specialist volunteers always on call and prepared to respond immediately to any disaster in Taiwan or overseas. Cooperating with foreign engineering experts, the Foundation also developed a “privacy-friendly tent” that is open at the top and can be set up in one minute. Inside, there are two beds, a table, and chairs. Liu Jun-an, head of the Tzu Chi Foundation’s public relations department, notes that “the tents provide privacy, but they also have the effect of getting evacuees to lower their voices. Mental security and maintaining a calm atmosphere are extremely important in an evacuation center.”

Reflections on the 2018 Hualien Earthquake

A major reason for the improved response in Hualien County in 2024 is the consideration that took place in response to the 2018 Hualien Earthquake, in which 17 people lost their lives.

Yang Yu-lu, a division chief in Hualien County’s Social Affairs Department, recalls the chaos at one emergency shelter following the 2018 earthquake: “Waves of anxious people flooded into the stadium designated as a shelter. They all slept together in a huddle, making a lot of noise.” Hualien County’s director of health, Zhu Jiaxiang, who was also involved in response efforts, reflects on his memories from six years prior: “It was absolute chaos. Everyone was unfamiliar with disaster relief procedures. Filling in the paper-based medical questionnaires for the evacuees took a long time, and many of these records got wet and dirty.”

An evacuation center after the February 2018 Hualien Earthquake. earthquake. There are makeshift beds, but the partitions are not yet in place (© Cheng Chung Lan).

Following the 2018 earthquake, volunteers and organizations from all over Taiwan came to Hualien to help—but ended up causing turmoil. With no one in charge of allocating personnel, it took a long time to get help to the victims.

In response, Hualien County revised its disaster relief implementation guidelines. The new guidelines set out the responsibilities for reporting after a disaster, methods of communication, and other important issues requiring prior consideration.

The most important issue emphasized by the new guidelines was “response speed.” Furthermore, subsequent training clarified the roles of not only government actors but also civil society organizations, so that they would also be ready and organized in an emergency.

This seemed to have a material impact in 2024. Support for evacuees came rapidly, including the deployment of privacy-friendly tents. Furthermore, civil society organizations provided a wide range of services, including psychological care, hot meals, the management of evacuees’ medical histories using barcodes, and on-the-spot diagnoses using artificial intelligence. The appointment of community “advisors” to coordinate support during a disaster to prevent duplication of effort was also effective.

The magnitude and regional characteristics of the Hualien County and Noto Peninsula earthquakes were different, so this comparison should not be taken too far. It may nevertheless help identify issues and ideas for consideration ahead of Japan’s next major disaster.

Three Crucial Features of Taiwan’s Disaster Response

Aota Ryōsuke is a professor at the University of Hyōgo researching Taiwan’s disaster prevention and response measures. He believes three crucial features distinguish Taiwan’s relief efforts: first, a top-down approach that allows for a quick response; second, support that makes use of civil society’s strengths; and third, a whole-of-community information sharing system built on the digital cloud.

In terms of the first feature, the Hualien County magistrate and other senior officials visited the disaster sites and evacuation shelters immediately after the earthquake. They also set up a disaster response headquarters that shared information on the situation and decided on countermeasures. The central government also sent the vice president to the area in the afternoon of the day of the disaster. The following day, the Taiwanese premier announced the government’s support policy in front of evacuees.

Rescue workers prepare relief supplies on April 5, 2024, after the earthquake in Hualien, Taiwan. (© AFP).

Professor Aota points out the practical importance of on-site visits: “If a leader waits for information to come up from subordinates, the response is likely to constrained from the outset. By going to the disaster area and interacting with victims, a leader can better recognize the scale of the problem and the most important immediate needs. In such cases, leaders may realize the insufficiency of existing policies faster than they would if they waited for bottom-up advice. Of course, these visits also encourage the victims.”

In terms of the second feature, Taiwanese civil society organizations like the Tzu Chi Foundation have accumulated experience and know-how in disaster response as the traditional provider of relief services. In 2024, without waiting for instructions from the government, they took immediate action and drew on the resources of the community. They set up tents at evacuation shelters and provided psychological care for evacuees.

A system had also been established and refined enabling the government to request support from civil society organizations. Local governments and nongovernmental groups met daily and held evacuation drills and training sessions in anticipation of a disaster. The government was able to ascertain in advance which organizations could provide what kind of support and expertise. This meant that the shelters in 2024 offered a diverse menu of services, including mental health counseling, meals, and even massage services.

In Japan, on the other hand, local social welfare councils are usually the contact point for volunteers. These councils are nonprofit, private-sector organizations, with weaker connections to municipal governments. They tend to emphasize restraint at the outset of a disaster, preferring to see a stabilization of the situation before encouraging volunteers to enter the field. This often puts a brake on the provision of community support—something that was also true for the Noto Peninsula quake.

The third feature, Taiwan’s digital cloud-based information sharing system, is known as EMIC (Emergency Management Information Cloud). As well as facilitating information sharing between various government agencies from the central government down to the village level, some of the information is also open to the mass media, citizens, and civil society support groups. This means that problems arising at evacuation centers can be seamlessly understood and addressed using the full resources of the community alongside government actions. Professor Aota believes this openness of information facilitated 2024’s quick response in Hualien County.

According to the Cabinet Office, Japan’s information sharing system for disaster relief supplies is only available to those involved in government administration. Furthermore, even those involved in government administration were not aware of how to use it effectively during the Noto Peninsula earthquake.

Japan Begins Improving Disaster Relief

In December 2024, just before the one-year anniversary of the Noto Peninsula earthquake, the Cabinet Office revised its local government disaster response guidelines for the first time in two years. The focus was placed on improving sleeping, eating, and toilet conditions in evacuation centers during disasters. The government’s hand was forced by widespread public awareness of the conditions experienced by Noto Peninsula evacuees.

The new guidelines align with the internationally accepted Sphere standards for humane living conditions following a disaster by specifying requirements such as “one toilet for every 20 people” and “3.5 square meters of living space per person.” The guidelines also suggest providing higher quality meals using mobile “kitchen cars,” promote the stockpiling of cardboard beds, and detailed measures for ensuring adequate water supplies for daily use, including for temporary baths.

Sakai Manabu, Japan’s minister of state for disaster management, stated at a recent press conference that the government wanted to see improvements to the conditions and relief efforts at evacuation centers nationwide “so that conditions will be the same at any disaster-stricken area in Japan.” At a press conference on December 24, Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru also expressed his determination to strengthen the role of the soon-to-be established Fire and Disaster Management Agency in improving the environment of evacuation centers “based on the Sphere standards, which in turn are based on human rights.”

Ultimately, however, the management of evacuation shelters is the responsibility of local governments. They are restrained in their response by the situation on the ground following a disaster and local realities. In regions like the Noto Peninsula, depopulation is progressing, and local governments often do not have sufficient financial resources or staff. This makes it difficult for them to confidently and smoothly respond to emergency situations.

Furthermore, the Noto Peninsula situation was compounded by the time of year that the earthquake took place. One local government official shared that “not only residents but also people who had returned home for the New Year’s holidays flooded into the evacuation shelters. We had no choice but to put everyone together haphazardly.” The official also noted that the environments in evacuation shelters vary by locality, so even if guidelines are prepared, it is not clear whether they will be implemented as written. For example, the official pointed out that “in some areas residents are very close-knit, and they believe that partitions and tents are not necessary or desirable. It is therefore important to respond according to the situation.”

Sakai similarly said, “we assume that in an emergency there will be chaos. We also understand that in some places it will not be possible to create an environment that meets the standards.” The minister nevertheless shared his expectation that local governments “conduct training and various other drills in advance so that they can respond as best they can.”

Making the Most of Civil Society

Professor Aota points out that simply drawing up detailed guidelines and expecting them to be implemented at evacuation sites is not enough. Without experience, know-how, practice, and outside support, it can be difficult for local governments to respond flexibly. He argues that the key lesson to be learned from the Taiwan experience is that “rather than having local government staff take full responsibility, we should work together with civil society. By engaging people and organizations in the community in advance, and training with them, we can draw on their strengths when disaster strikes.”

(Originally published in Japanese December 29, 2024. Banner photo: Evacuees in the elementary school gymnasium in Wajima, Ishikawa, that served as an evacuation center following the Noto Peninsula earthquake. More than a week after the disaster, the living environment was still not adequate. January 12, 2024. © Kyōdō.)

Related Tags

Ishikawa earthquake disaster Noto evacuees Taiwan evacuation