Images of Home: Photographer Finds Hope Among Ruins on Noto Peninsula

Disaster Images Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A year has passed. Still, the images of that fateful moment on New Year’s Day when the earthquake unleashed chaos on the Noto Peninsula remain fresh in my mind; the horrific and tragic scenes burned into my memory.

Disaster Strikes

It all felt like a bad dream. The 7.6-magnitude earthquake that struck on the afternoon of January 1 left the Noto Peninsula in ruins. The shaking, which registered the maximum 7 on the Japanese seismic intensity scale, made short work of so many of the area’s old, wooden houses. The temblor cruelly ravaged the peaceful landscape, upturning lives and livelihoods in an instant.

The charred remains of Wajima’s famed morning market on January 22, 2024. The earthquake sparked a fire that destroyed over 200 buildings and incinerated some 50,000 square meters of the city. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

The destruction took different forms: fire swept through Wajima’s historic morning market, devouring stalls; tsunami up to five meters high slammed into villages along the coast; tremors severed electricity, water, and communications and caused cracks, sinkholes, and landslides that made roads impassable, hindering rescue efforts. It was nearly impossible to assess the scale of damage to communities amid the turmoil—at one point, more than 30 villages were completely cut off from the outside world. The situation was a losing race against time.

A road rendered impassable by the quake in the Monzen district of Wajima on January 11, 2024. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

Major closures along sections of the Noto-Satoyama Kaidō, the main north-south artery, snarled traffic, slowing transportation to and from the peninsula to a crawl. The simple task of driving from Noto to Kanazawa, typically a two-hour ride, turned into a grueling undertaking taking as much as 10 hours to complete.

Collapsed homes spill onto a road in the Shōin district of Suzu on January 23, 2024. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

First responders raced to rescue victims. However, the constant sound of their efforts—Self-Defense Force vehicles rumbling along roads, ambulances and fire engines blaring their sirens, helicopters passing overhead—formed a cacophony that further frayed nerves and added to the sense of unease.

A blanket of snow falls on collapsed homes in the Shōin district of Suzu on January 24, 2024. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

My first concern was for the wellbeing of my family. I was on the road when the earthquake struck and was able to evacuate to Kanazawa, but the area of Wajima where my parents’ home is had been completely cut off. I tried to reach there by car on January 2 only to find the road impassable. Returning to Kanazawa, I prepared for another attempt two days later. Taking my car as far as the roads allowed, I covered the rest of the way on foot, following a mountain trail for two hours to reach the village. After three days of isolation, my sister could hardly contain her surprise at seeing me; the look of disbelief on her face remains a vivid memory.

Relief washed over me at finding my family safe, but it was tinged by an intense sorrow at the wretched state of the peninsula. It weighed heavily on my heart to realize that so much of the landscape that I had come to know and love had been irrevocably altered. As a Noto resident and photographer, I felt compelled to do something—anything—and so from mid-January, camera in hand, I set out to document the aftermath of the disaster and recovery efforts.

A Sense of Duty

My family moved around a lot when I was young, but I consider Wajima, where my father is from, to be home. The natural beauty of Noto and its stirring festivals speak to me, and I have spent the last 10 years conveying the wonders of the peninsula to the world through my photography and design work. To then watch as the earthquake lay waste to all that I had worked for was almost too much to bear.

The disaster took a heavy toll on a number of Noto’s landmarks. Parts of Mitsukejima, a tree-topped island towering off Suzu’s coast, crumbled into the sea, robbing the islet of its iconic shape. Huge cracks were opened in Shiroyone Senmaida, a steep slope of terraced rice paddies overlooking the sea in Wajima, and the irrigation system feeding the fields was heavily damaged, making it hard to say when farming at the site could resume.

Mitsukejima framed by the remnants of a tsunami-damaged sign on January 17, 2024. Although battered, the island remains a beacon for residents. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

The 1,004 paddies that make up the Shiroyone Senmaida on February 2, 2024. The earthquake cracked the walls and other parts of the terraced fields. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

Evacuees that I met and people who reached out to me on social media urged me to use my camera to bring attention to the plight of their towns and villages, and that is what I have tried to do.

Images of Resilience

Surveying the damage wrought by the earthquake and tsunami was extremely unsettling. The terrifying scenes hardly felt real. Was I in the right place, or had I wandered into an alternative world where space and time were twisted?

The Ukai district of Suzu on February 7, 2024. The destruction attests to the force of the earthquake and 3-meter tsunami that struck the area. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

Access to Noto improved from mid-March as work on the transportation network progressed, bringing with it much-needed support of volunteers from across Japan. Their presence and kind words were a tremendous source of encouragement to residents.

A seasonal tradition across the peninsula is the Kiriko Festival, with communities holding their own versions of the celebration from summer to autumn. The name derives from massive lanterns called kiriko that participants parade through the streets to the accompaniment of spirited chants, drums, and gongs. Considering the scale of the disaster, I had assumed that it would take several years for such events to reappear, but many towns put on the festivals as usual, a decision that speaks to the determination and resolve of locals. The excitement brought smiles to the faces of residents, whose energy and spirit shone bright despite the uncertainty they face in rebuilding their lives.

Participants parade a kiriko from Jūzō Shrine through the Wai district of Wajima on August 23, 2024, passing through neighborhoods with collapsed homes and other disaster damage. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

The jubilance of the young people carrying the kiriko gave voice to the shared determination to restore the community’s vibrancy, the powerful energy embodying the first steps toward recovery.

Defying the disaster, a summer festival gets into full swing on August 23, 2024. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

The demolition of collapsed and damaged homes began in earnest around six months after the disaster. As of November 2024, a third of structures, some 10,000 buildings, slated to be demolished through funding by the Ishikawa prefectural government had been removed. The pace of work has since increased and is expected to be completed by October 2025.

Demolition work in the Noroshi district of Suzu on November 27, 2024. Volunteers and demolitions companies have been a vital part of the reconstruction effort. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

While the demolition process is gradually removing the piles of rubble and debris, at the same time it is erasing all traces of the lives once lived in those places. Many lots where homes once stood are now overgrown. I fear that as the landscape of Noto changes, its memories are being lost.

Empty lots spread across the Takojima district of Suzu on December 11, 2024. Nearly half of the 7,000 homes scheduled for demolition in the city have been cleared as of the end of November. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

Memories and Recovery

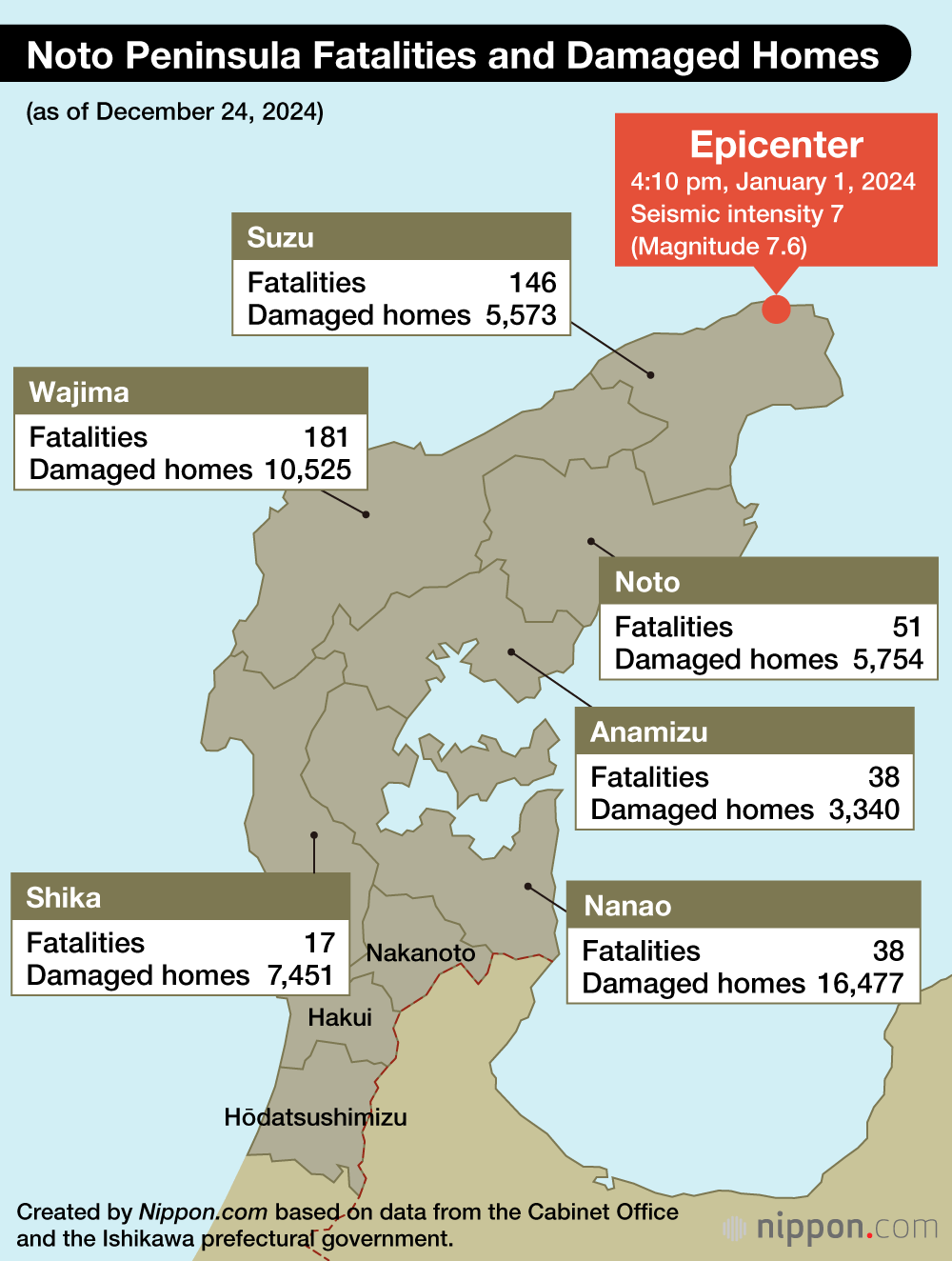

On December 17, the Ishikawa prefectural government announced that the death toll from the Noto Peninsula Earthquake had reached 469. The overall figure is expected to exceed 500 when fatalities from other prefectures and disaster-related deaths are included in the tally. A survey found that close to 100,000 buildings were damaged in the disaster.

As recovery efforts got into full swing, many areas suffered a second disaster in the form of heavy rains that hammered the Noto Peninsula in September. The earthquake has exacerbated the depopulation issue gripping the region, and flooding only compounded the challenges communities already face.

Flood damage in the Monzen district of Wajima on September 27, 2024. The deluge from heavy rains resulted in 16 deaths and damaged 1,368 homes. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

Recovery looks different to different people depending on their circumstances. Still, the messages of encouragement offered to Noto residents by volunteers and others who have offered their assistance fill me with hope that the peninsula will bounce back.

Symbolic of this hope is an encounter I had while out photographing disaster-stricken areas. It was a rainy day but looking up at the dull sky I was surprised to find a clear patch over the ocean where a rainbow had appeared. For a few moments, the collapsed houses and the shimmering sky came together in a heart-rending landscape. I have included my photograph of the scene at the top of this article as a symbol of hope for the future for residents of Noto.

Cleared lots in the Kawai district of Wajima on December 18, 2024. Demolition work in the city is expected to be completed by the end of March 2025. (© Yoshioka Eiichi)

The situations in disaster-stricken areas are in constant flux, and I realize that my photographs may be the only means of conveying certain aspects of Noto life. The beautiful nature, rich culture, and fabulous traditions are not merely a part of the peninsula’s heritage but are vital resources that must be preserved and passed on to future generations. As a photographer, I intend to continue playing a role documenting these to provide a shining light for the hopes and desires of Noto residents.

I hope that in writing this article, I can reach a broad audience and inspire readers to remember the Noto Peninsula Earthquake, turning their thoughts to the region’s current situation and its path ahead.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A rainbow appears over the coastal waters in the Orito district of Suzu on November 27, 2024. © Yoshioka Eiichi.)