So Long, Spring and Autumn: Japan Losing its Four Seasons to Climate Change

Science Disaster- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Human-Driven Climate Disaster

If Heian-period writer Sei Shōnagon was penning her classic work The Pillow Book today, she might not have started it with the poignant phrase, Haru wa akebono—In spring, the dawn. She would have likely missed the season all together—and autumn for that matter—as winter weather is rapidly giving way to summer heat with little more than a nod to spring. As climate regime shift steams ahead, and even if the world gets CO2 emissions under control, Japan may find its cherished four seasons irreversibly whittled down to two.

The consequences of this shift go far beyond aesthetics, though, and are already having a devastating human impact. Annual deaths from heatstroke have climbed to around 1,000—10 times that of storms and floods—making spells of extreme heat one of the country’s most lethal disasters. What is more, humans are the cause as we fuel global warming with our unchecked emissions.

The last few years have been marked by record heat in Japan. (© Pixta)

There is no shortage of doubters who claim that changes in the climate have natural and normal causes and are not the result of the buildup of greenhouse gases like CO2. While it may be difficult to determine what is right and what is wrong, a sober look at the scientific data points quite clearly to humans as the culprit for the warming the planet.

Take, for instance, the claim that the changes in solar activity are the cause of worsening heat waves. Increased solar activity certainly impacts the earth, causing spectacular auroras or disrupting radio communications, but there is no compelling evidence linking the sun’s roughly 10-year cycle of activity to changes in the weather. Data does not show the cyclical rises and falls in record temperatures that would be consistent with peaks and lulls in solar activity. Rather, it exhibits a sustained upward trend in record heat that is in step with rising greenhouse gas emissions.

Winds and a Warming North

Changes in atmospheric and oceanic conditions make Japan particularly susceptible to extreme heat. One driver is a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification, whereby the rapid melting of polar sea ice, which helps cool the Earth by reflecting solar radiation back into space, results in more of the sun’s heat being absorbed, causing the high northern latitudes to warm faster than other areas.

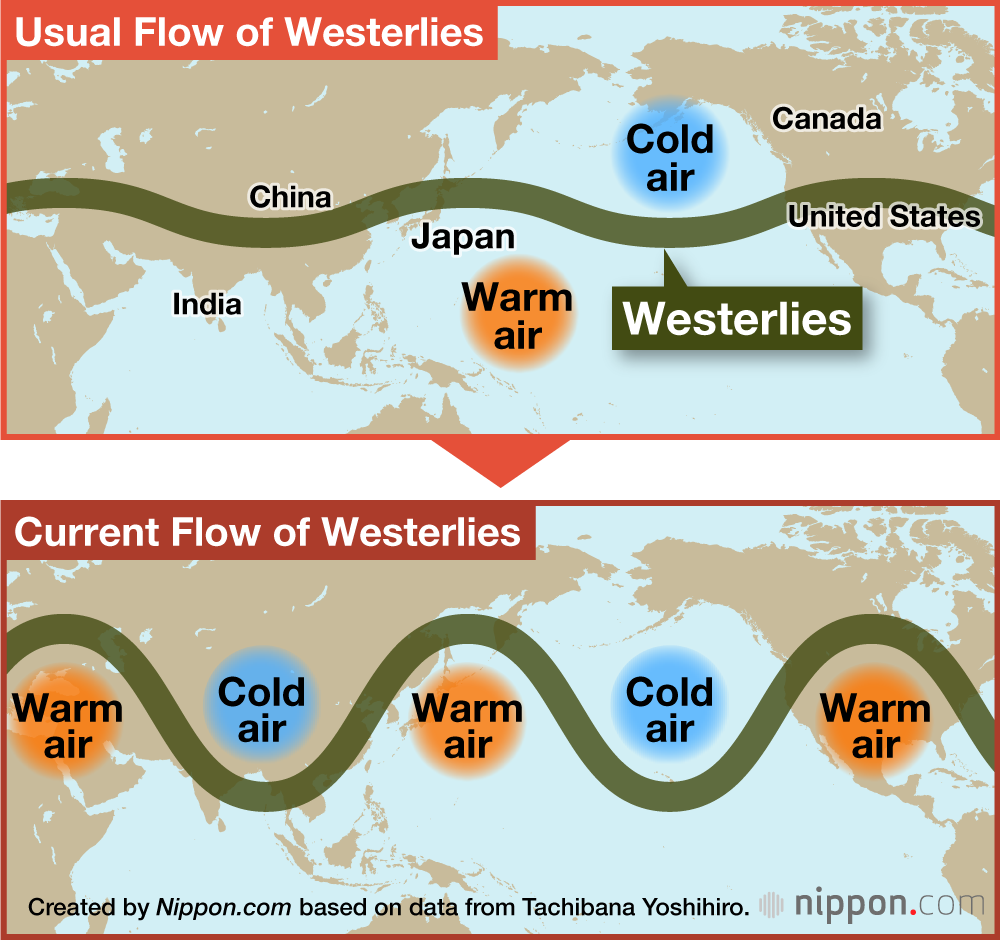

This warming has shifted the meandering flow of the northern westerlies, strong east-to-west winds in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere that help regulate the climate there by serving as a boundary between cold Arctic air to the north and warm subtropical air to the south. The westerlies follow a wave-like trajectory, creating arcing troughs and ridges. During the summer months, ridges are associated with warm air and sunny weather, but they also give rise to prolonged spells of stifling heat. These occur when high-pressure systems develop under the ridges, with the combined clockwise rotation holding the warm fronts in place.

The snaking trajectory of the westerlies is typically subdued if the river of air is moving quickly, but grows more pronounced as the winds slow. The greater the difference in temperature between the poles and the equator, the faster the westerlies flow. As the Arctic has warmed, though, the temperature differentiation has narrowed, and since 2010, the normally gentle, meandering of the winds has intensified to a degree rarely seen before, giving birth to deep ridges that engulf Japan in warm air and push the mercury upward.

If ridges keep on the move, the spells of wilting heat are short lived. However, the wildly undulating westerlies produce a phenomenon known as Rossby waves, the phase of the wave pattern that moves westward due to the Earth’s rotation and counteracts the predominantly eastward flow of the winds, effectively locking ridges in place and producing extended periods of extreme heat in specific locations.

As the westerlies are undulating, it would seem just as likely that a cold trough settle over Japan in summer as a ridge of warm air, but this is not the case. As land masses heat more readily than sea water, warm air forms over the Eurasian continent in summer, propelling the westerlies northward near Japan. This mass of heat from the continent makes its way eastward, engulfing Japan and causing the westerlies to swing up and over the hot air as if trying to evade it. This pattern makes Japan prone to heatwaves even in normal years, but it is now driving temperatures ever higher as it becomes more pronounced.

Warming Waters

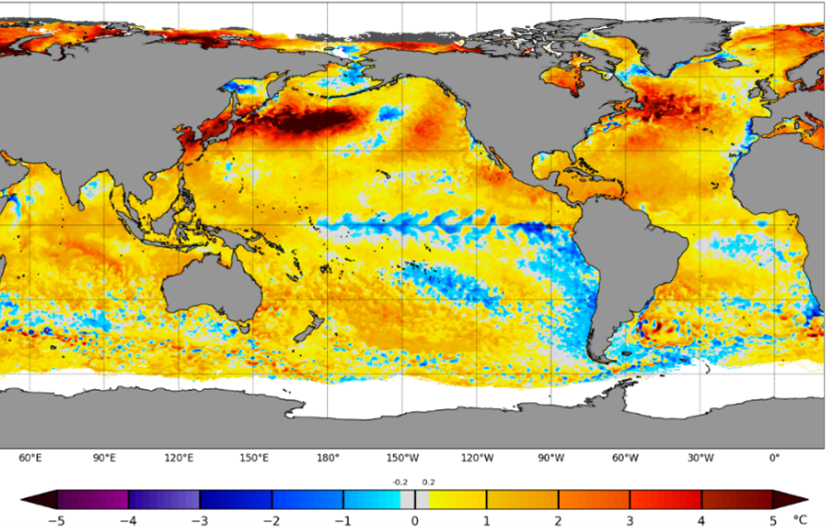

The ocean is also a prime factor in Japan’s stifling weather. Global warming is raising surface temperatures at a steady rate, with the waters around Japan among those heating most rapidly. The ocean’s surface is typically slow to cool, so even as autumn approaches, the lingering heat gives rise to unseasonally hot sea breezes that make for muggy conditions on land.

A map from the website of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows global sea surface temperatures in mid-September 2024. Areas colored in yellow, red, and black indicate, in ascending order, where temperatures are above normal. (© NOAA)

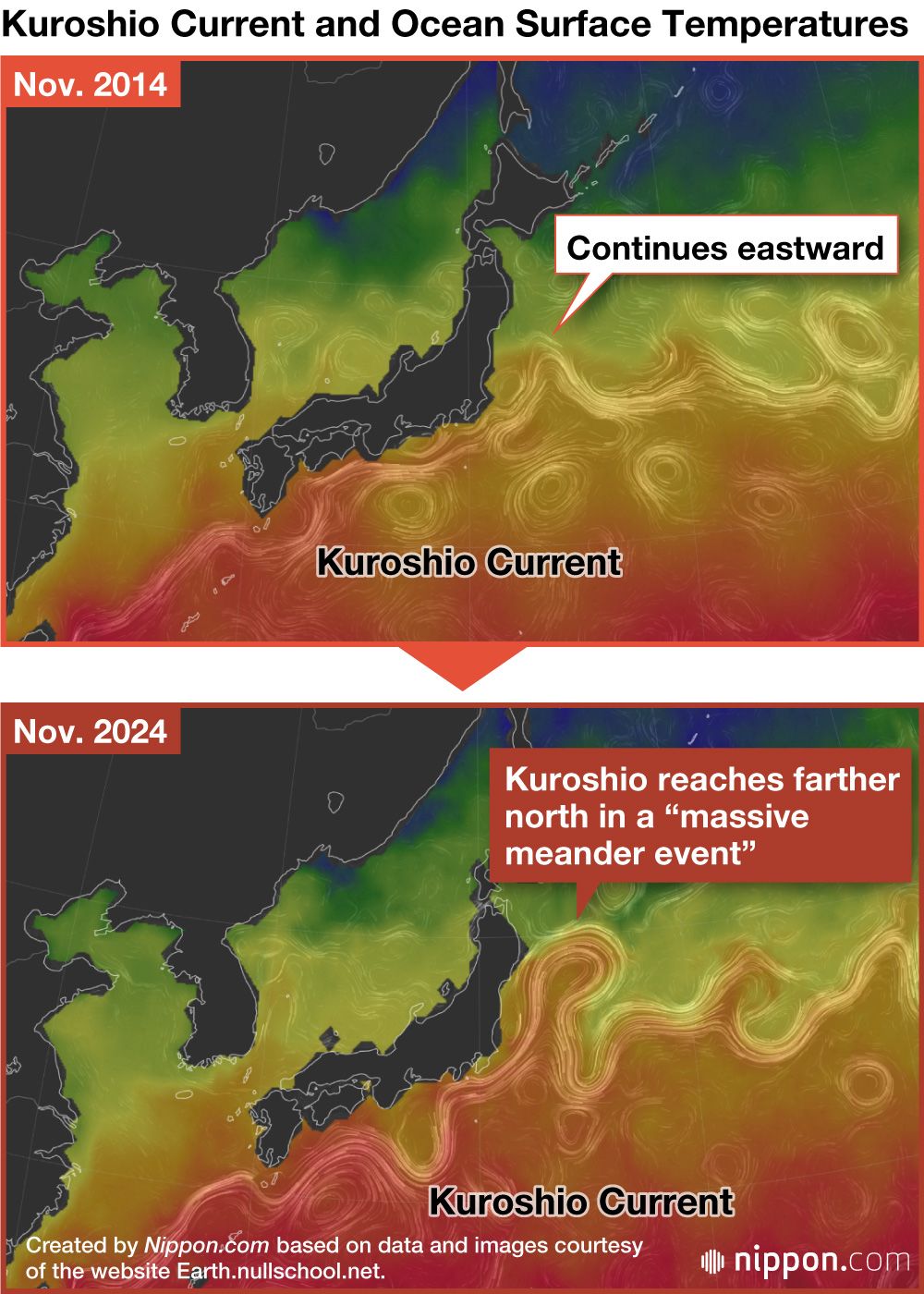

This warming is impacting the course of the Kuroshio Current that flows northward along Japan’s Pacific coastline. The stream of warm water typically makes its way up from the Philippines, passing by the Ryūkyū Islands, Kōchi, the Kii Peninsula, and Shizuoka before bending eastward into the open ocean. However, the last few years have seen the current wildly undulate in its course, bending to the south near Kōchi and then swerving back to slam into Japan around Shizuoka. Off the coast of Chiba, it detours north, heading up the Pacific coast toward Hokkaidō before curling southward once again off Iwate.

The first recorded occurrence of the Kuroshio Current reaching as far north as Iwate and the waters south of Hokkaidō was an unprecedented anomaly, and it has occurred two years running. The intrusion of the current has raised the surface temperature of the waters off Tōhoku and southern Hokkaidō by over 5 degrees Celsius when the Kuroshio is running there. It is known that even a sea surface temperature that is just 2 degrees higher than normal is abnormal, so the situation is quite abnormal at the moment.

The abnormal condition, which I call the “massive meander” of the current, is also raising temperatures in the waters on the opposite side of Japan via the Tsushima Current, a branch of the Kuroshio that flows through the Sea of Japan. The currents together hold Japan in a vice grip of warm water, raising summer temperatures and keeping them high well into autumn.

Fueling Floods

Warmer sea surface temperatures are behind the uptick in torrential downpours like those that lashed the quake-hit Noto Peninsula in September 2024. As the sea heats, vast amounts of water vapor are released into the atmosphere, forming moisture-laden clouds that dump their content over land in a deluge. The same mechanism was behind the flooding that ravaged parts of Spain in fall 2024 as abnormally high surface temperatures in the Mediterranean Sea created ideal conditions for heavy rains.

Flooding in Japan after torrential rains. (© Pixta)

Every part of Japan is at risk from torrential rains as long as the conditions for spawning them—global warming-driven extreme heat and rising sea surface temperatures—remain in place. In this sense, calling the Noto floods a natural disaster is misleading as it ignores the clear human element in their genesis. The only hope for preventing such calamities from becoming commonplace is to reduce our CO2 emissions.

Winter Snowfall

Many climate deniers cite record snowfalls in arguing against a warming planet. Stories of blizzards snarling transportation routes and homes buckling under the weight of accumulated snow lend veracity to this line of reasoning, as does the fact that snowstorms claim more lives in Japan than windstorms and flooding. However, winters are getting warmer overall, not colder, and it is this heating trend that is increasing the frequency of cold snaps and extreme snowfall events.

A person clears a path through a mountain of snow. (© Pixta)

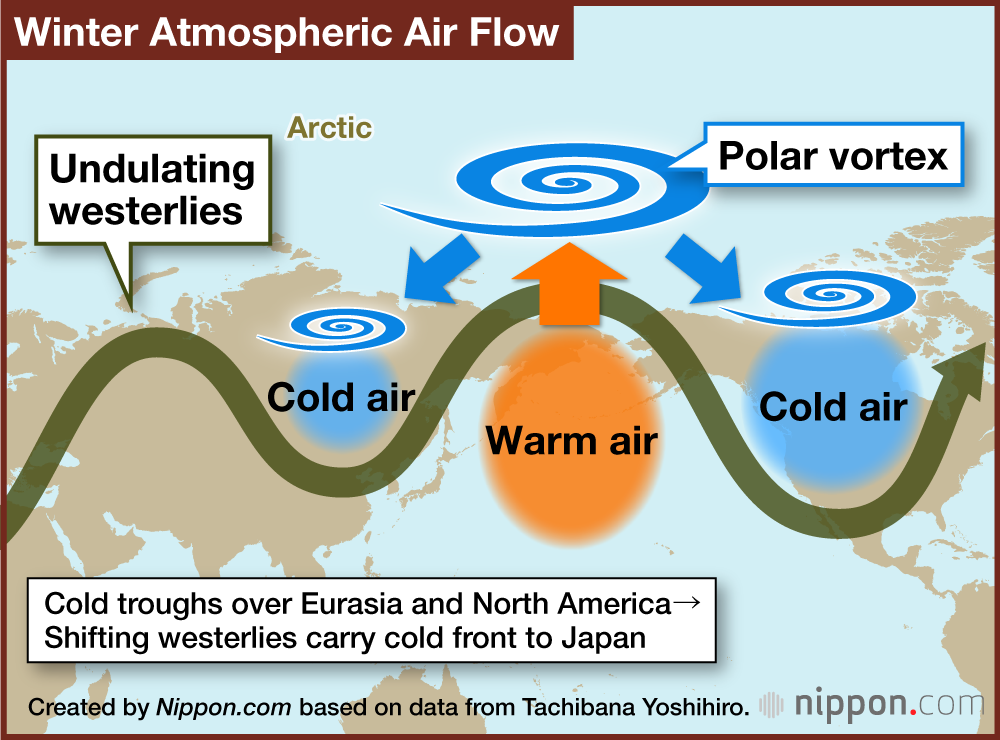

Again, the culprit is the wildly meandering westerlies. In a reverse of the pattern seen in summer, recent winters have seen the undulating wind currents form large cold troughs over wide swaths of Eurasia, including portions of Japan, and North America that enable frigid Arctic air to move south. These cold masses are drawn to areas where sea surface temperatures are higher—somewhat similar to the way that opposing poles of a magnet are attracted to one another—making Japan a particular target for severe snowstorms.

As I mentioned above, the drastic loss of polar sea ice is a major reason behind the pronounced snaking of the westerlies. The atmosphere above Alaska is warming as the surrounding sea ice thins, prompting the westerlies to veer northward out of the path of the warming ocean surface. As the winds meander more drastically in a north-south direction, they divide the Arctic cold air into east-west segments. Once split, these cold masses spill southward to envelope East Asia and North America.

As cold air moves toward East Asia from Siberia, it splits into two streams centering on Mount Paektu on the Korean Peninsula, passing around the peak before reconverging over the Sea of Japan, creating what is known as the Japan Sea polar air mass convergence zone, or JPCZ. The stream of cold air absorbs moisture emanating from the warm sea currents of the Sea of Japan, forming band-shaped clouds, sometimes referred to in the media as “linear snowbelts,” that dump snow on Japan, particularly along the Sea of Japan coast. Snow from these events accumulates rapidly and such storms are often characterized as “snow bombs” to emphasize the need for caution.

In a worsening case of cause and effect, global warming is raising sea surface temperatures and worsening extreme heat, which in turn is producing heavy snowfalls. It goes without saying, then, that as the sea warms, Japan faces an ever-greater risk of severe snow events.

Standing at Hell’s Gate

Japan is already prone to natural disasters, and as I illustrated above, the situation will only get worse as the planet warms. Climate change should be a top issue for both the government and residents of Japan.

This is far from the case, however. The fact of the matter is that large swaths of the population remain indifferent to the risks posed by global warming, which is a major concern. Speaking at the 2023 Climate Ambition Summit in New York, UN Secretary-General António Guterres expressed his distress over extreme weather events, declaring that “humanity has opened the gates of hell.” Echoing Guterres, I describe mankind as standing on the precipice of another world, where extreme weather like 40-degree Celsius summer temperatures will no longer be an anomaly, but the norm.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres at the Climate Ambition Summit on September 20, 2023. (© Jiji)

Humanity is on the verge of crossing a number of climate tipping points, critical thresholds that will trigger accelerated—and potentially irreversible—consequences. I consider one of those boundaries to be when the sea surface temperature rises by 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to 100 years ago. Oceans are heat sinks, absorbing much of the extra heat in the atmosphere. As such, they play an important role in moderating summer heat and absorbing greenhouse gases. However, they have become less effective at this as surface temperatures rise. The amount of warming stands at more than 1.4 degrees as of 2023, potentially putting us already past the point of no return.

The heating of the oceans, which cover 70% of the Earth’s surface, will play a key role in ferrying us into “another world” marked by extreme weather. It is still not too late to turn back by coming together and doing what it takes to reverse the rise in sea surface temperatures. There is no time to lose.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image: A map from the website of the Japan Meteorological Agency showing sea surface temperatures around Japan on September 21, 2024. Red areas mark where temperatures are above normal. © Japan Meteorological Agency.)