An Uji Encounter with Centuries of Tea Tradition

Food and Drink Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Genuine Tea Experience in a World Heritage Setting

The city of Uji, Kyoto, is well known for Byōdōin, a Buddhist temple listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Nearby is another popular tourist site, though—one where visitors can have a genuine sadō (tea ceremony) experience. This is Taihōan, a tea house operated by the Uji municipal government. It sits just across from the famed temple’s Phoenix Hall, as befits its name, which literally means “hermitage opposite the phoenix.”

Visitors pass through a rustic gate to reach Taihōan. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

Visitors can watch and drink matcha (powdered green tea) from Uji, famed for its tea farms, prepared and served in the sadō tradition. The tea is accompanied by a seasonal Japanese sweet and a simple explanation of the tea ceremony and its steps provided by a sadō master.

The tea is prepared with soft water boiled slowly in an iron kettle heated over charcoal. Tea is served in raku teabowls, handcrafted in Kyoto. The bowls are chosen to match the season—for example, a design featuring heads of rice for October, when rice is harvested.

A bowl of matcha is served at Taihōan. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

The tea experience requires reservations in advance. After watching the tea master prepare a bowl of tea, participants enjoy traditional sweets before trying their hand at whisking matcha themselves. The tea masters, who change daily, hail from various sadō schools, including the mainstays, Urasenke and Omotesenke. Repeat visitors may notice the differences in each school’s techniques.

The main approach to Byōdōin is lined with old purveyors of tea, cafés, restaurants, and sweets shops, and packed with tourists meandering the street with a matcha latte, ice cream, or other treat in hand. Tea is available in all forms—loose leaf, powder, and teabags among them—and in all price brackets, and many businesses have their own educational exhibits.

In November 2024, the local newspaper Kyoto Shimbun reported that the explosion in the popularity of Uji matcha tea among foreign tourists was causing shortages. Some stores have apparently begun imposing limits on the amount each shopper can purchase.

The street approaching Byōdōin is lined with tea houses and traditional confectioners. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

Two Factors that Sparked a Boom

The Made in Uji brand has now gained global recognition. Its popularity can be traced to two factors.

The first was the so-called Häagen-Dazs Shock of 1996. In that year, the US ice cream manufacturer released a green tea product containing matcha, which led to a jump in the production and cost of the tencha used to make the powdered tea. It also touched off a boom in matcha-flavored sweets. Then, in 2000, coffee chain Starbucks began selling matcha-flavored drinks. Its popularity spread globally, causing the so-called Starbucks Shock, further boosting matcha sales.

Since then, matcha’s popularity has only increased: According to Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, production of tencha in Japan has almost tripled, from 1,430 tons in 2012 to 4,176 tons in 2023.

Seeking World Heritage Listing for Ancient Japan’s Drink

Uji tea’s prestige can be attributed to the area’s unique environment and the devotion of locals to production techniques. This part of Japan was recognized long ago as an ideal place to cultivate tea. The Uji and Kizu rivers flow through the area, and it is blessed with a high annual rainfall. Its slightly elevated, sloped terrain has good water drainage and frequent fog, inhibiting frost that could damage tea sprouts.

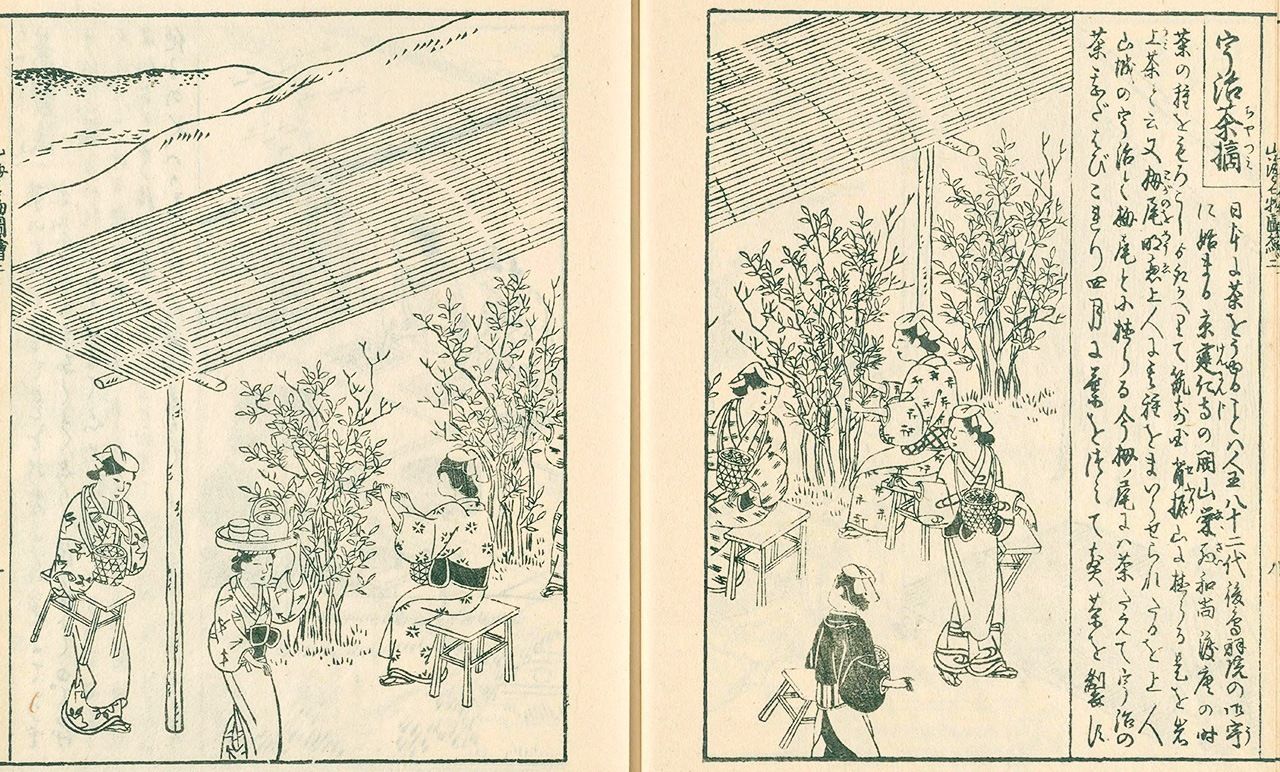

Tea cultivation was first introduced to Kyoto during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), and during the subsequent Muromachi period (1333–1568) the shogunate encouraged the development of tea plantations, helping to build Uji tea’s first-class reputation. In the mid-Edo period (1603–1868), the Nihon sankai meibutsu zue (Illustrated Famous Products of the Mountains and Seas of Japan) explained the transmission of tea and the origins of Uji tea. It also described cultivation and harvesting in Uji and detailed the processing techniques, suggesting that Uji tea was already a widely recognized brand throughout Japan.

“Picking tea in Uji” from Nihon sankai meibutsu zue. (Courtesy National Diet Library digital collection)

Now, Uji tea refers to tea that is processed by Kyoto-based producers using traditional techniques, although the tea may be cultivated in Kyoto or one of three prefectures close to Uji: Nara, Shiga, or Mie. Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs has designated the tea culture of southern Kyoto Prefecture’s Yamashiro region as “Japan Heritage” in recognition of its importance to sadō, itself a form of Japanese spirituality, and the region’s role in producing leading types of Japanese tea: powdered matcha, ordinary green leaf sencha, and the highest-quality gyokuro. Kyoto Prefecture is also leading an initiative to have the so-called “cultural landscape” of Uji’s tea registered as World Heritage.

Flavor Enhanced by Shade

In Uji, tea grown to produce tencha (which is dried and powdered as matcha) and the top-quality gyokuro is shaded for the final few weeks prior to harvesting to protect the leaves from intense sunlight. This prevents a key flavor component, theanine, from altering to produce catechins, which are bitter. The result is smoother-flavored tea. Tea cultivation under shade in Japan was described by Christian missionaries in the early seventeenth century, and the technique was transmitted to the West.

Tencha, tea grown in the shade of traditionally woven straw matting, for making matcha. (© Pixta)

Experiencing Tea and Its History

Visit the Tea and Uji Community Center Chazuna, close to Keihan Uji Station, to learn more about the history and cultural background of Uji tea. Chazuna has digital displays, areas to touch and experience tea, and a range of cultural experiences on offer, including decorating your own tea canister, harvesting the plant, and even grinding tea leaves to make matcha.

Chazuna features digital exhibits explaining the history of tea. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

At Chazuna, you can try using a millstone to grind tencha. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

The matcha-making experience, where visitors grind tea with a millstone, is popular with tourists, including families with children. After grinding the matcha, you can drink it alongside professionally ground tea to compare the difference. According to the center’s head, Sakayori Naohito, “When whisking tea, the key is to not be too forceful, to ensure it is mixed quickly, incorporating more air to produce a creamy texture.”

Other facilities in Uji have their own experiences on offer, including drinking different brands of tea to guess which is which, and opportunities to craft tea utensils.

There are even tea plantations in the center of Uji itself, and Chazuna has a terrace overlooking tea fields. Harvesting of sencha takes place in three stages from April through the summer months. But Uji’s tencha and gyokuro are harvested just once a year, and picking is still done by hand.

In the Muromachi period, the shōgun’s family and other powerful provincial lords (daimyō) owned tea plantations in Uji, collectively known as the “seven famous tea fields of Uji.” Of these, the only one which remains today is Okunoyama-en, in the Zenhō district of Uji.

Tea fields in Uji. The plants are grown under shading to avoid direct sunlight. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

Traditional Techniques for More Aromatic Tea

Tencha is steamed in a special steamer, then heated and dried in a separate device. The dried leaves can then be ground by millstone to produce matcha. Gyokuro, meanwhile, is produced by harvesting young tea leaf buds grown under shade, which are then steamed and kneaded as they are dried.

Fukubun Seichajō, a tea factory in a residential district near Byōdōin, uses traditional cultivation and processing methods to produce tencha. It was founded in 1901, and still uses a century-old tencha drying machine, invented in Uji in 1924. The device uses heated tiles to dry the tea leaves with radiant heat, producing a distinctive aroma.

According to the factory’s fifth-generation owner Fukui Keiichi, they steam the young tea leaf buds for around 30 seconds, then dry them at around 200°C before separating the stalks from the leaves. “Our tile tencha drying machine is very special. It has been passed down since my great-grandfather’s days.”

Fukui Keiichi of Fukubun Seichajō explains how their historic factory uses heat and wind to produce full-flavored tencha from Uji-grown tea. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

A Tea House Visited by Toyotomi Hideyoshi

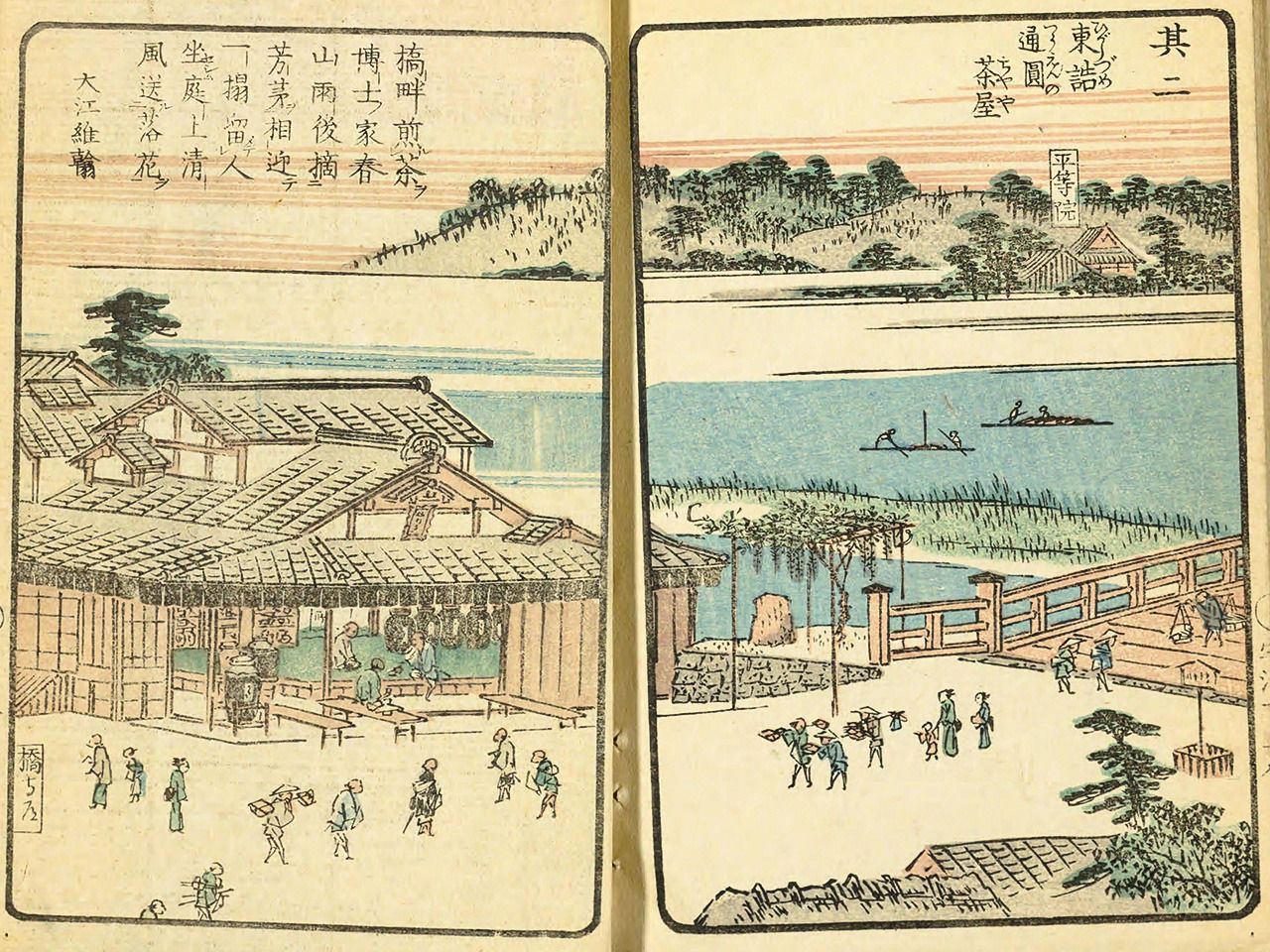

Close to Uji Bridge is a tea house named Tsūen that looks as if it is right out of a period drama. Over 850 years ago, it played a role in guarding the bridge, while also serving tea to travelers passing through. It is mentioned in historical novels, and even in Japanese dictionaries.

Tsūen, near Uji Bridge, is Japan’s oldest tea house, tracing its history back to 1160. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

The present building dates back to 1672. Inside, there is an array of tea urns on display dating back hundreds of years, and a wooden statue of Tsūen’s founder, received from the renowned Zen priest Ikkyū Sōjun (1394–1481). Records exist of visits to the tea house by such historic figures as shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436–90), the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–98), and the shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616).

Tsūen also stocks top-shelf matcha produced by the aforementioned Fukubun Seichajō. According to the shop’s manager, the twenty-fourth-generation owner Tsūen Yūsuke, the high-grade matcha is particularly popular among visitors from Japan and abroad alike.

Tsūen tea house, seen in the Ujigawa ryōgan ichiran (Sights on the Banks of the Uji River), printed in 1863. (Courtesy the National Diet Library digital collection)

In addition to selling various styles of Uji tea, they serve matcha-flavored sweets. There are benches outside where diners can try mildly bitter tea-flavored dumplings, matcha parfait, Uji azuki bean soft-serve ice cream, and other treats while enjoying views of the river and Uji Bridge.

Matcha served with dango dumplings at Tsūen tea house, Uji. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

An Old Tea Wholesaler Becomes a Popular Shop

There are many specialist tea purveyors in Uji that trace their origins back for generations. Nakamura Tōkichi Main Store is a popular establishment dating back to 1854. Located on the high street leading to Uji Bridge, it is always buzzing with tourists.

Nakamura Tōkichi Main Store, close to JR Uji Station. The shop building was originally a tea wholesaler. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

Nakamura Tōkichi Main Store offers a range of seasonal products and has a tasting corner. Visitors can compare the different colors, aromas and flavors of the teas for sale. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

The store features striking white plastered walls and latticework, a typical style used by wholesalers in the Meiji era (1868–1912). In 2009, it was selected as a Cultural Landscape of Japan. Various teas are available for tasting in the former tea drying area of the wholesaler. The tea processing factory, built in the Taishō era (1912–26), has been refurbished as a café. Make a reservation to try your hand at grinding matcha, then imbibing it in the tea ceremony as either koi-cha (thick tea) or the thinner usu-cha.

The Nakamura Tōkichi Main Store café is inside a refurbished former tea processing factory. Its attractive garden is another delight. (© Fujiwara Tomoyuki)

The café has a central atrium in the ceiling, a legacy of the original tea processing factory, when it allowed heat from the processing to escape. The pillars still bear numbers jotted down by former employees, evoking images of the once busy workplace. The café’s most popular treat is its striking Maruto parfait. The dessert is served in a bamboo cylinder and contains matcha-flavored ice cream, chiffon cake, and jelly combined with other ingredients such as shiratama (rice flour dumplings) and raspberries. Another favorite is the namacha jelly, with a distinctive matcha taste and topped with ice cream, creating a taste (and texture) sensation. Nakamura Tōkichi operates another store and café close to Byōdōin.

Popular sweets at Nakamura Tōkichi Main Store include Maruto parfait (foreground) and namacha jelly. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)」

A Mind-boggling Variety of Matcha Foods

Walking through central Uji, you cannot help but notice the incredible array of matcha-flavored food and drink on offer. Matcha takoyaki (octopus balls), croquettes, beer . . . You could spend an entire day consuming the tea in wildly diverse forms.

According to locals, a traditional favorite souvenir is the dumplings called matcha dango. There are also unusual combinations, such as mitarashi dango, or skewered dumplings with a sweet soy glaze; dumplings topped with roasted kinako soy flour; matcha rusk cookies; matcha kintsuba (sweetened beans wrapped in dough)’ and fruit dipped in matcha chocolate.

An endless range of matcha-related souvenirs is available in Uji. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

The Birthplace of Sencha Leaf Tea

Uji also has deep connections with sencha, the green tea most commonly consumed in Japan. Ōbakusan Manpukuji is a local temple established by Ingen (1592–1673), a Buddhist monk from China who introduced sencha culture to Japan. Baisaō (1675–1763), a Japanese monk from the temple, is considered to have helped popularize sencha tea culture and to have founded Senchadō, a sadō practice using sencha. Within the temple grounds stands Baisadō, a shrine built in Baisaō’s honor. The All Japan Senchadō Federation has its headquarters alongside the temple and holds an annual tea event here. In 2024, Japan’s Council for Cultural Affairs deemed that the temple buildings represent important culture introduced from Ming Dynasty China (1368–1644), and requested designation of its three main structures as National Treasures.

Baisadō, built in honor of the monk Baisaō, who trained at Manpukuji. (© Pixta)

(Originally published in Japanese. Research and text by Matsumoto Sōichi and Fujiwara Tomoyuki, Nippon.com. Banner photo: Enjoying matcha sweets at the Nakamura Tōkichi Main Store café, near JR Uji Station. The Council for the Promotion of the Ujicha Region has certified numerous Uji tea cafés in the city. © Fujiwara Tomoyuki.)