Building a World-class Volleyball League from the Ground Up

Sports- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan Volleyball League Rebranded as the SV. League

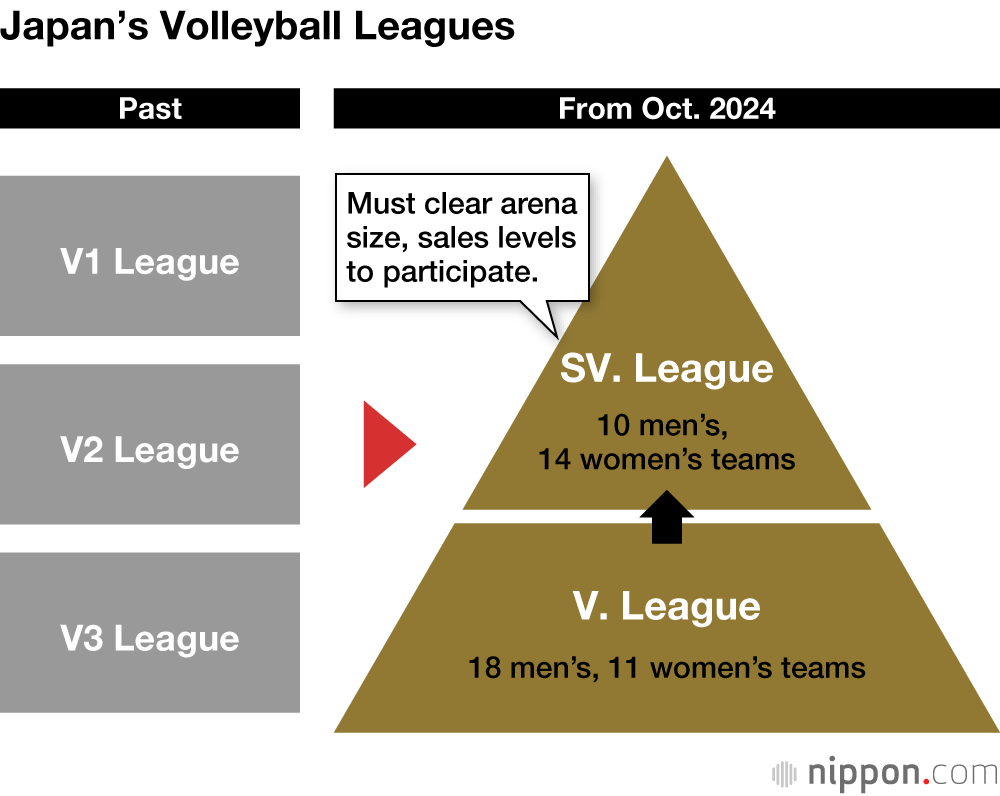

Japan’s first national volleyball league was formed in 1967. Three years earlier, the Japanese women’s national volleyball team, dubbed the “Oriental Witches,” won the gold medal at the Tokyo Olympics. The popularity of volleyball rose steadily, with many major corporations in Japan establishing teams that then joined the professional league.

The Japanese women’s volleyball team, nicknamed the “Oriental Witches,” competing for the gold medal at the 1964 Tokyo Games against the Soviet Union. (© Kyōdō)

In the 1990s, the emergence of the professional soccer J. League in Japan, which fielded teams in regions across Japan, led to a change in volleyball as well. Inspired by the new soccer development, the Japan Volleyball League was dissolved to be rebranded as the V. League.

However, the rebranded league failed to achieve the professionalization of the J. League. Instead, it continued to remain centered on conventional corporate-sponsored teams, so that fans did not look on the new league as being very innovative.

The problem was compounded by the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble in the 1990s. In the wake of the collapse, a wave of companies decided to suspend or discontinue their sports teams. One volleyball team after another disappeared, including such leading men’s teams as Fujifilm and Nippon Kōkan KK, as well as the women’s teams Hitachi and Unitika.

New developments in professional volleyball unfolded under the changed social conditions, including the relaunch of the former men’s team Nippon Steel Sakai as a club team called the Sakai Blazers. The idea was also put forward in 2016 of creating a professional league within two years under the name “Super League.” However, the league did not gain support for this move toward professionalization, and remained linked to a management system centered on corporate teams.

Philosophy Underlying the Shift to the SV. League

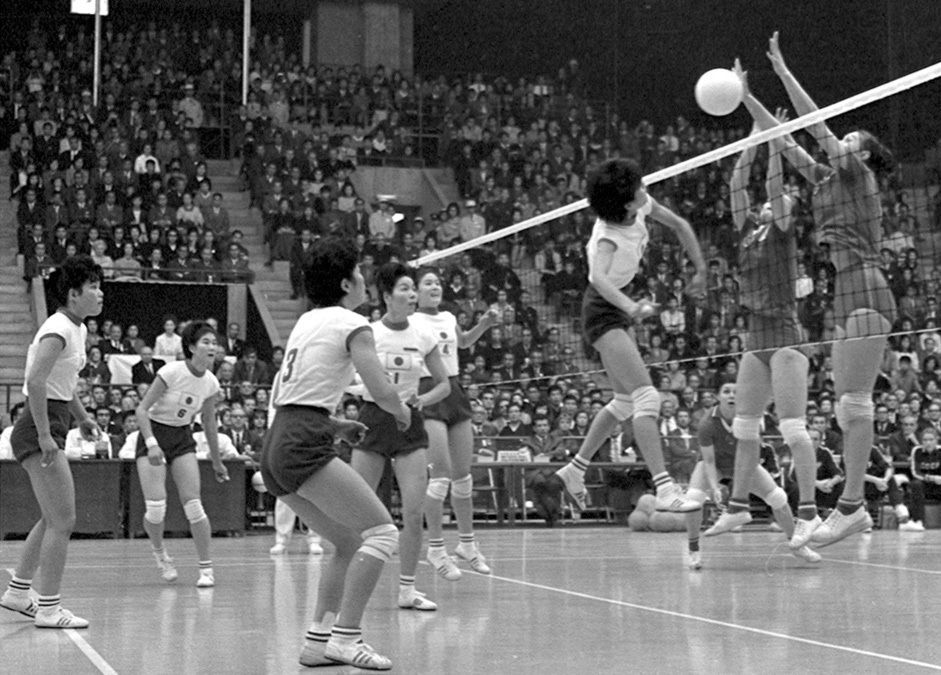

The V. League, which was in existence until the 2023 season, has been reorganized so that the first division is now known as the SV. League, while the second division is called the V. League. The “S” in the new name stands for “Strong, Spread, Society,” reflecting the philosophy of being robust, broad-based, and connected to society.

At the press conference for the opening of the league, Chairman Ōkawa Masaaki commented that the milestone “marked a new start as we aim to become the world’s premier volleyball league,” and he expressed the hope that the reorganized league would “fully showcase the appeal of volleyball.”

Chairman Ōkawa Masaaki flanked by players at the September 30 press conference held in Tokyo’s Minato Ward to mark the opening of the new SV. League. (© Jiji)

Ōkawa has management experience in both the J. League as well as the professional basketball B. League. Building on this experience, how does he define the goal of becoming the “world’s premier” volleyball league?

According to Ōkawa’s explanation, the goal is to become the world’s best in terms of attendance and retail sales through a strengthening of management and governance. Additional goals are for a member team to win the club world championship and to have the largest number of national team players participating in the Olympics and in the Volleyball Nations League.

The SV. League got off to a good start, boosted by the strong interest in Japan’s national team during the Paris Olympics. The men’s opening match was broadcast live on the terrestrial Fuji Television network, and all league matches for both men and women are broadcast by J Sports, a satellite broadcaster.

However, some have pointed out that the difference between the new league system and its predecessor is not clear. In terms of the organizations of the teams, the number of foreign players has increased, but there are concerns that awareness of the launch of the new league may not be so broad among members of the general public who are not yet volleyball fans.

The number of teams in the league that do not use corporate names is increasing, such as the men’s teams Osaka Bluteon (formerly Panasonic) and Hiroshima Thunders (formerly Japan Tobacco), as well as the Okayama Seagulls (municipally owned) and Victorina Himeji (independently financed) in the women’s league. But overall, the teams retain the tinge of corporate sponsorship, making it difficult for the league to showcase its innovation or appeal to fans hoping to cheer for a local squad.

European League Revitalized by EU Integration

In Europe, meanwhile, professionalization of volleyball has been a success in Italy and elsewhere, and the sport is becoming increasingly multinational as players from various countries play on the same teams. For example, 7 of the 14 members of the Italian Serie A club Perugia are foreign nationals, including Japanese ace Ishikawa Yūki. According to the club’s website, its roster includes imported players from Poland, Ukraine, Cuba, and Argentina, in addition to Japan.

Ishikawa Yūki cracks a smile during an Italian Serie A Super League match between Perugia and Trentino held on October 27, 2024. (© IPA Sport/ABACA/ Kyōdō)

This trend is not limited to volleyball. With the integration of the European Union, European athletes have been able to move freely within the market since the late 1990s. They are now treated in the same as ordinary workers. Especially in the case of soccer, the transfer market has been active and the level of play in each country has risen. Also, clubs have begun to receive large fees from broadcasting rights through the spread of pay TV, and player transfer fees have also skyrocketed. More players from outside of the EU have been attracted as a result of the expanded scale of business.

In addition, the European sports world has a history of development rooted in the local community. Each club is supported by dedicated local fans, who cheer on players from other countries as representatives their own hometown. Revenue from ticket sales at stadiums and arenas also serves as the foundation for further business development.

Promoting Community-oriented Activities a Must

Japan likewise requires a foundation in the community in order for the scale of business to expand. In the case of soccer, efforts have been made to promote the sport in local areas ever since the creation of youth leagues. Basketball has also focused on expanding its base by promoting “mini-basketball” for elementary school children. Efforts like these have fed the success of the J. League and B. League.

However, many other sports remain centered on school club activities or corporate-sponsored sports, and have struggled to penetrate local communities. Volleyball seems to be one such case.

According to the “Sports Life Data for Children and Youth” survey conducted by the Sasakawa Sports Foundation in 2023, an estimated 1.81 million teenagers play volleyball at least once a year, down from the 2.79 million marked in the 2001 survey. In other words, in just over 20 years the number has shrunk by nearly 1 million.

Given Japan’s declining birthrate, the number of people competing has decreased for many sports. If the foundation for a given sport shrinks rapidly, the number of spectators will naturally decrease in turn, hindering business development.

Making Under-15 Teams Mandatory

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology began an initiative last year to shift from club activities at public junior high schools to community-based clubs. The burden placed on teachers tasked with coaching school clubs was the biggest problem to overcome. But this reform has been difficult because few leaders and organizations in the community are able to take over this coaching role that has made it necessary for teachers to even work on weekends.

Resolving such issues also needs to be a point of focus for the SV. League. One initiative that has been introduced already is the requirement that any club seeking a license to join the new league must field an under-15 team for young players. Ideally, the league will be able to expand its training and promotional activities further and focus on improving the competitive environment.

Up to now, the world of Japanese volleyball has attracted attention by using the success of the national team as a catalyst. But the Olympics are only held once every four years, presenting a limit to how much this event alone can contribute to the sport. The popularity of volleyball is not sustainable solely on the basis of a few players who are given celebrity status.

For the development of the league, world-class players, competitive play, and business success are indispensable. However, in order to spark and sustain these conditions, it is necessary to nurture as many young volleyball players as possible and increase the number of volleyball fans who will follow the sport over the long term. There are no shortcuts to becoming the world’s best. The only way is for the league to keep its eyes on the ball and continue to make steady progress.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Osaka Bluteon’s Nishida Yūji, left, spikes the ball past Suntory defenders in the second set of the opening match of the SV. League held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium on October 11, 2024. © Jiji.)