Japan Struggles to Find a Site for Its High-Level Radioactive Waste

Politics Environment Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Three-Step Process

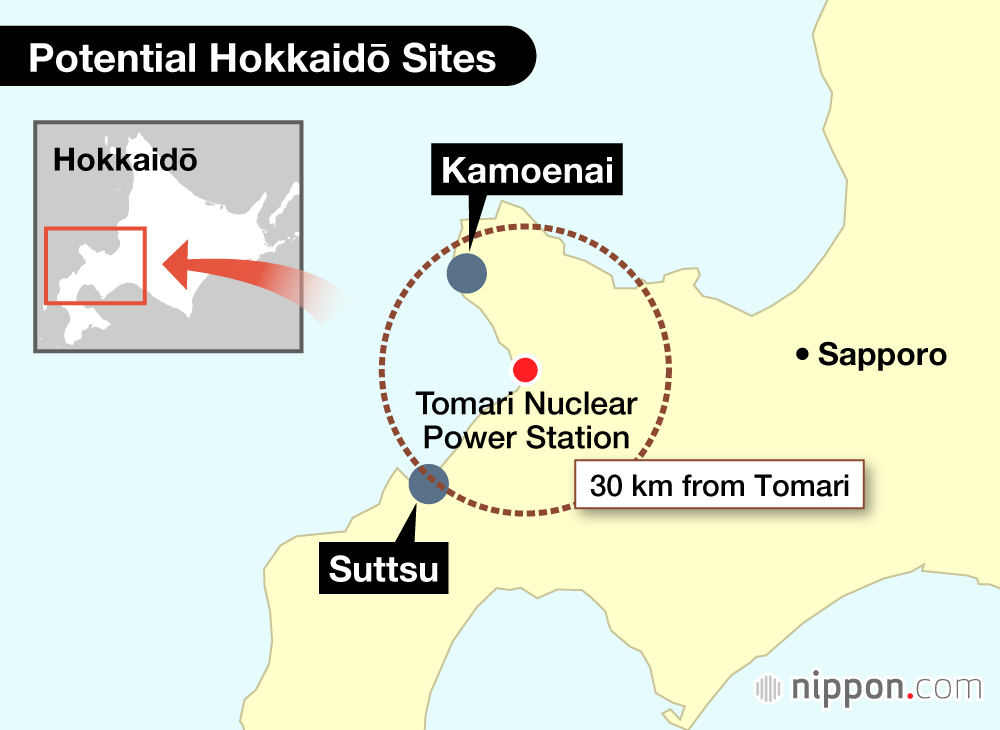

The Japanese government and nuclear power plant operators have long grappled with how to dispose of spent fuel and other high-level radioactive waste. Authorities finally settled on the approach of burying waste deep underground at facilities 300 or more meters below the surface. In 2002, NUMO, the Nuclear Waste Management Organization of Japan, began hunting for a storage location by inviting municipalities to put themselves forward as candidate sites. To date, this “volunteer” policy has netted only three participants, the towns of Suttsu and Kamoenai in Hokkaidō and Genkai in Saga.

On November 22, NUMO submitted a report on the results of its literature surveys for the two Hokkaidō municipalities, which were initiated in November 2020, concluding that research can progress to the second stage in Suttsu and part of the southernmost area of Kamoenai.

Suttsu, a small coastal community of some 2,600 people situated in the southwest of Hokkaidō around 140 kilometers to the west of the capital of Sapporo, boasts rich fisheries and was the first municipality in Japan to host an onshore windfarm. Kamoenai, a town of around 800, sets in the southeastern corner of the Shakotan Peninsula about an hour’s drive north of Suttsu and is famed for its catches of sea urchin, scallops, and squid. Both towns are roughly the same distance from the Tomari Nuclear Power Plant, the only nuclear power station on the northernmost of Japan’s four main islands, and like many other rural areas in Japan, they face the dual demographic crunch of an aging and declining population.

The Tomari Nuclear Power Station (right foreground), with Kamoenai just visible some 16 kilometers further up the Shikotan Peninsula. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

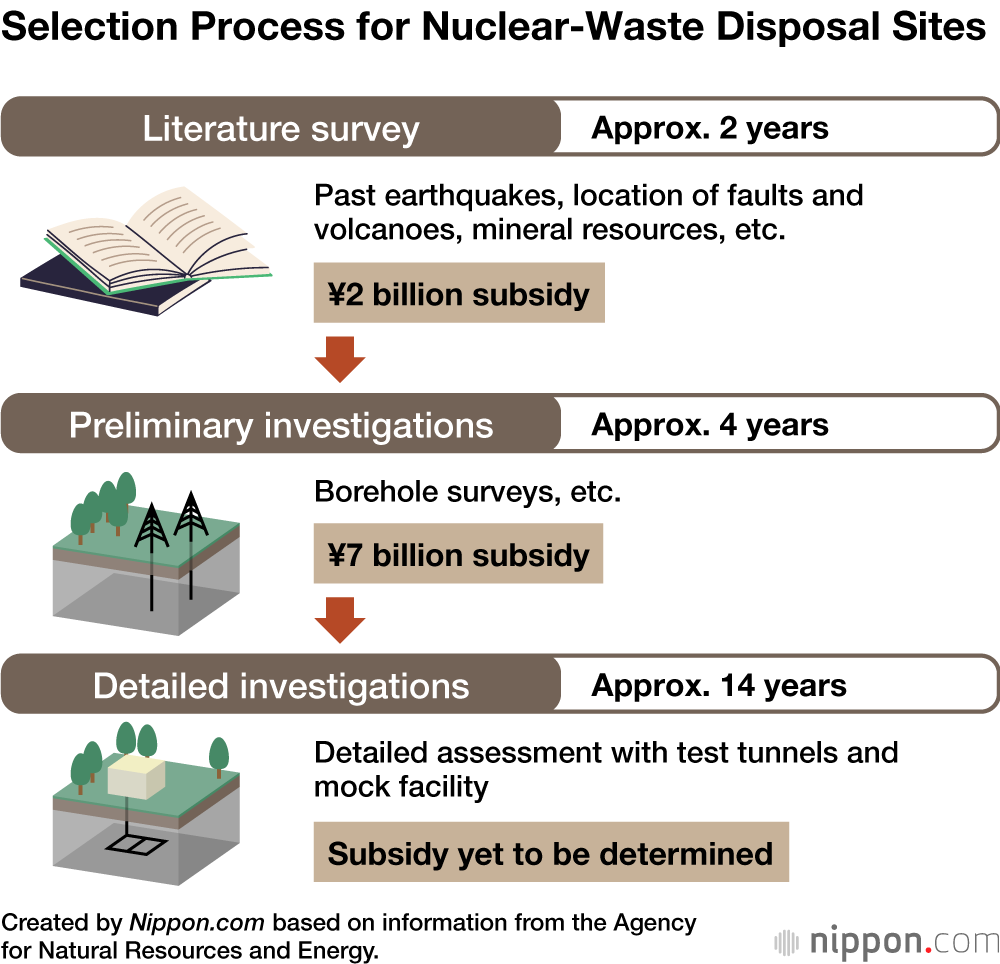

The first stage of the government’s three-step review process for deciding on a disposal site is a literature survey that involves analysis of geological information and research into the history of local volcanic and seismic activity. Having completed this, Suttsu and Kamoenai have been by greenlighted by NUMO to proceed to the second phase, a preliminary investigation that includes geological exploration and drilling surveys. The final step in site selection is a detailed investigation of the underground geology using test tunnels and other techniques. The government provides a ¥2 billion subsidy to municipalities taking part in the literature survey and an additional ¥7 billion for the drilling survey. The subsidy for the third stage of the process has yet to be decided.

Local governments must consent for the review process to proceed to the second stage, and Suttsu Mayor Kataoka Haruo has expressed his intent to hold a referendum on the issue, an approach that Kamoenai Mayor Takahashi Masayuki says he is also considering.

A Hot Button Issue

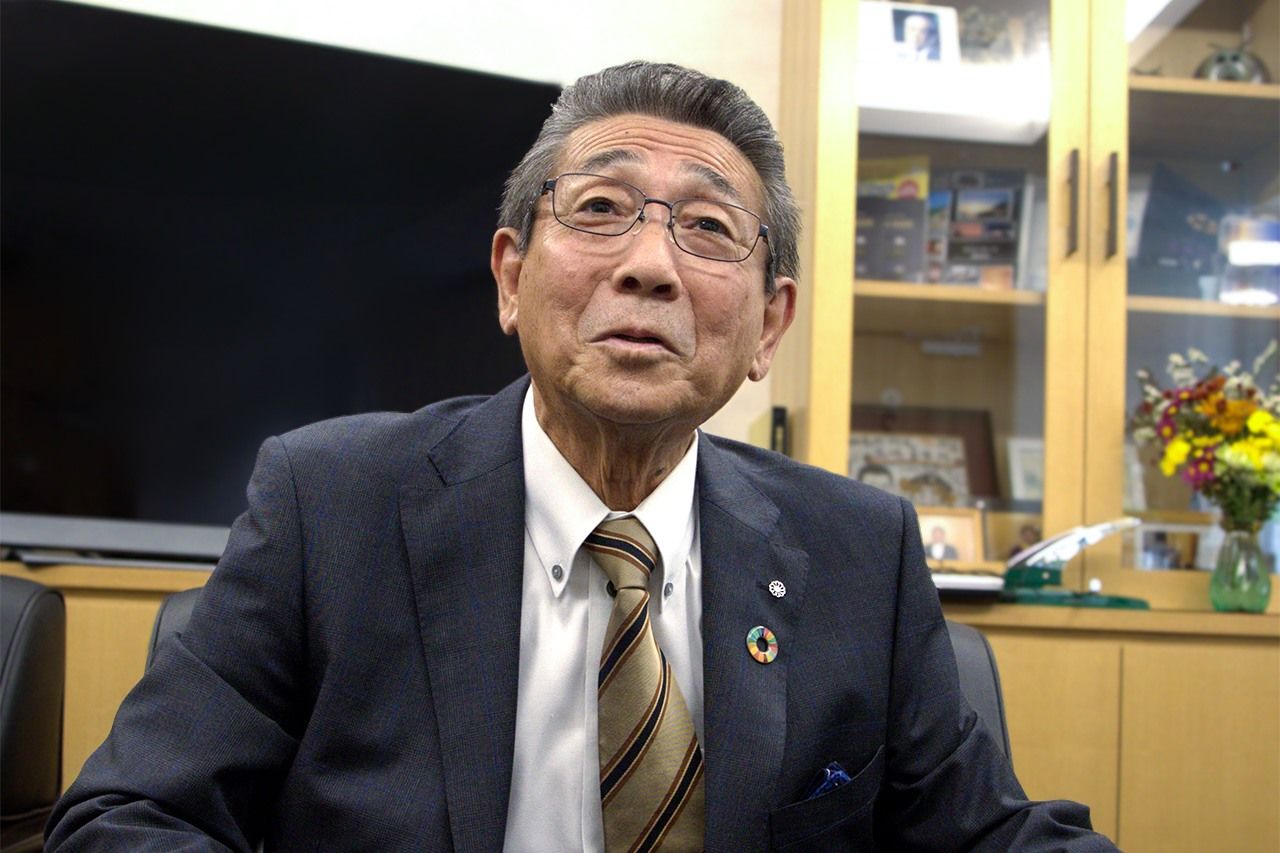

Kataoka says that he volunteered Suttsu for the literature survey as a way to kickstart the discussion about nuclear waste. “We’re going to have to dispose of it somewhere in Japan,“ he says. “That’s a fact that we all need to come to terms with.” Looking back, though, he admits that the experience has left him with mixed feelings. While it has forced residents to face up to the disposal issue, it also stirred an unexpected amount of ire. “I never imagined that a little town like ours putting its hand would be the target of so much vitriol.”

Suttsu Mayor Kataoka Haruo. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

Taking to social media and other online platforms, opponents of Suttsu’s move unleashed a rain of abuse, with some calling the town “a disgrace to Hokkaidō” and others vowing to shun its seafood and other products. Much of the anger was directed at city hall, including a rash of telephone calls and irate messages faxed to municipal departments.

Nishimura Nagisa of Suttsu’s tourism and local products association shows online comments critical of the town. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

Nishimura Nagisa, who as head of Suttsu’s tourism and local products association manages its social media presence, had the unsavory task of compiling the online calumny. The stream of negative posts sent chills down her spine. “The comments were almost uniformly nasty.”

From the start of the literature surveys, Hokkaidō Governor Suzuki Naomichi has voiced his opposition, saying that NUMO and the central government were “essentially throwing money in our face.” The four towns and villages neighboring Suttsu and Kamoenai have also expressed their unease, with some passing ordinances declaring themselves “nuclear-free” and others publicly objecting to nuclear waste passing through their borders in what many see as an attempt to set up a blockade. The tone in the media, too, has leaned toward the negative, with editorialists writing pieces harshly criticizing the surveys.

Opinions Divided Locally, Too

The literature surveys were accompanied by initiatives aimed at informing residents about the process. These included 17 dialogue sessions, information and study meetings, and a visit to the nuclear fuel reprocessing facility in Rokkosho in Aomori Prefecture.

Tanaka Noriyuki, who runs an electronics store in Suttsu, credits such efforts over the last four years with raising local awareness of the problem of nuclear waste. “It brought the issue home,” he says. “We all benefit from nuclear power, after all, so I don’t feel any group has the standing to oppose the survey process or object to discussing what to do with the waste.”

Tanaka Noriyuki. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

On the other end of the spectrum stand residents like Echizen’ya Yoshiki, who opposes the surveys. A member of Suttsu’s town council, he challenged Kataoka in 2021, running on a platform of ending the survey. Although he lost his bid for mayor, he continues to speak out, arguing that the decision to allow the literature survey to go ahead was premature. “Building a waste disposal facility will have far reaching repercussions for the town,” he declares. “The decision to start the survey should have been made after adequately informing residents, and only with their consent.”

Other residents echo his concerns, with many lamenting that it is no longer possible to calmly discuss the matter. “It’s important to that we talk about nuclear waste,” says Echizen’ya. “But it has become a sore spot for the community.”

Echizen’ya Yoshiki stands in a shed where he makes signs opposing the survey ahead of a local referendum on the issue. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

Every country reliant on nuclear power faces the long process of hashing out what to do with high-level radioactive waste that will remain hazardous for tens of thousands of years to come. Japan has opted for a “volunteer first” approach that includes the government offering subsidies to woo municipalities. One expert attributes this line of action to the fraught history of Japan’s nuclear power industry, saying that “the government faced major opposition every step of the way when building its fleet of nuclear power plants and wants to avoid heading down that rocky path again.”

The Lack of Incentives

The Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry and NUMO have conducted over 100 information sessions around the country, but the number of municipalities that have raised their hands to take part in the site selection process remains stalled at three.

Kataoka attributes the meager response to the volunteer aspect of the surveys and the government not being more proactive in its approach. “The central government says it’s going all out to find candidate sites, but it’s been a lukewarm effort,” he declares. “Mayors, after all, will balk at raising their hands if it means jeopardizing their reelection bids.” He argues that a more direct tack is needed, with the government directly inviting 10 or more candidate sites from around the country to take part in the surveys.

He also suggests increasing the subsidy amount for taking part in the literature survey. Suttsu used the ¥2 billion it received to build housing for nurses working in the town, along with other infrastructure projects, while Kamoenai invested a large portion of its money in refurbishing its port. Kataoka insists, however, that the amount is not in line with the burden placed on municipalities, declaring that “we put the much-needed funds to good use, but 2 billion yen is little recompense for what we’ve been through.”

A Process Stands in Place

In contrast to Suttsu, the literature survey has caused little controversy in Kamoenai. Mayor Takahashi insists that for the village and other places located near nuclear power plants, taking part in the process of finding a permanent disposal site is imperative. At the same time, though, residents need to be informed of the pros and cons of the issue. “It’s my hope to lay the groundwork to enable future generations to decide how to proceed.”

He laments the paucity of municipalities interested in participating in site selection research, which he attributes to the current approach. “I think to stoke debate on the issue, the government will have to put forward several candidate sites of its choice.”

Kamoenai Mayor Takahashi Masayuki. (© Matsumoto Sōichi)

Even with NUMO declaring Suttsu and Kamoenai eligible for the second stage of surveys, the consent of the governor and local legislative bodies are required to proceed, something that is far from guaranteed.

In response to the release of the NUMO report, Governor Suzuki said that he was opposed to preliminary second-stage investigations being carried out. The responses of the local assemblies in Suttsu and Kamoenai were not explicitly contrary, leaving room for continued debate but maintaining a reserved stance. An official with the Hokkaidō prefectural government sums up the current situation as bleak: “Considering that governors in other prefectures are unlikely to come out in favor of surveys proceeding, the government will need to come up with a new plan.”

Even if local and regional governments come out in favor of the second stage of surveys, there remains the possibility that the preliminary investigation will find the sites geologically unsuitable for storing highly radioactive nuclear waste. Experts, for instance, point out that Suttsu is near a fault line and that Kamoenai has a volcano looming nearby. On top of these, strata of weak and fragile rock crisscross the region. Together, they cast a considerable shadow over the government’s hopes for finding a site.

Looking to Finland for Ideas?

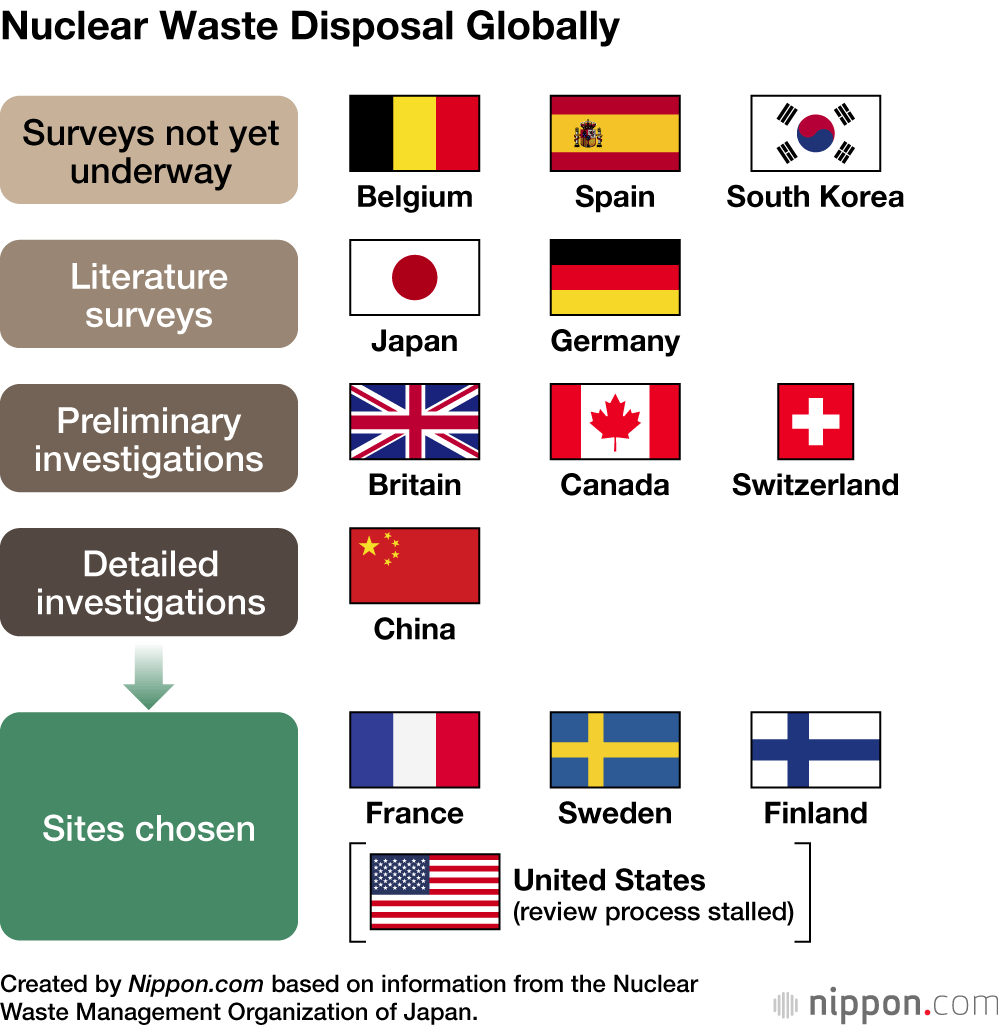

In its search for a permanent disposal site, Japan can look to Finland as a model. The Nordic country leads the world in nuclear waste storage with its Onkalo facility. The site, on the island of Olkiluoto off of Finland’s west coast, was selected in 2000 from among some 100 communities that put themselves forward to host the disposal facility. The selection process was marked by a high level of engagement with residents to win public trust.

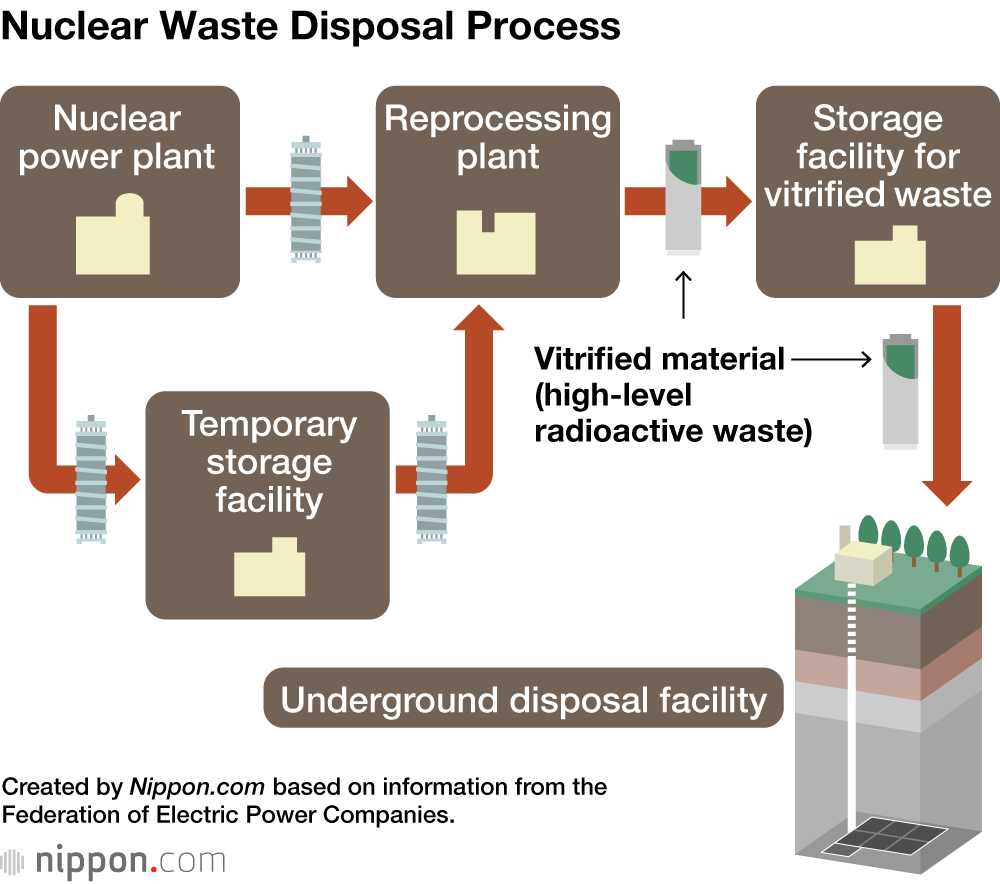

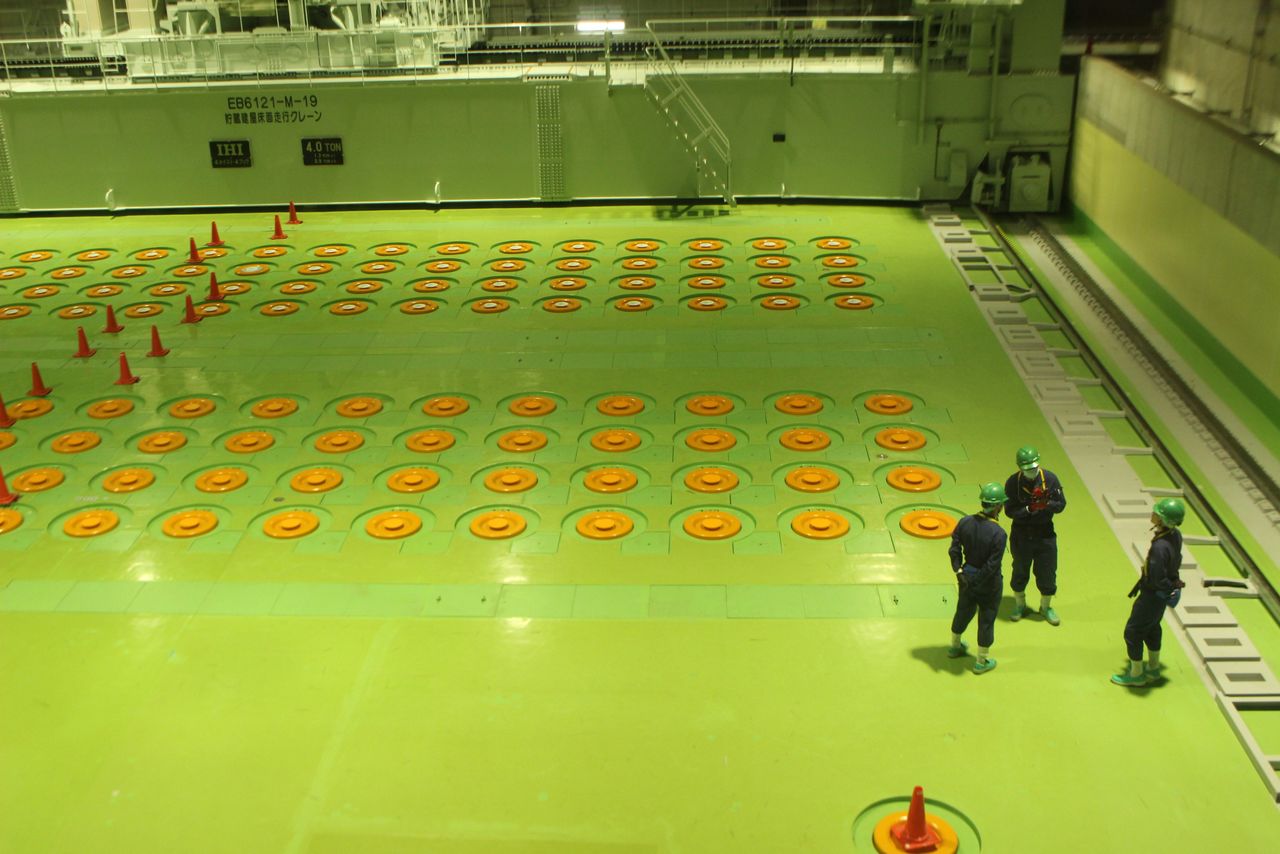

Japan currently has 19,000 tons of spent fuel rods in temporary storage at nuclear power plants. Mixing the material with molten glass, a process known as vitrification, to create a stable form, will produce 2,530 canisters of waste. This number jumps to 27,000 canisters when unprocessed nuclear waste is included, and experts advise that any permanent disposal facility will need to be able to store over 40,000 canisters. Japan’s current roadmap has a facility opening sometime between 2033 and 2037, but at the current rate of progress, it is highly unlikely that authorities will meet this timeline.

A facility in Rokkasho, Aomori, provides a temporary storage site for high-level radioactive waste produced during reprocessing of spent fuel from Japanese reactors. (© Jiji)

Breaking the Stalemate

A growing crowd of experts view the current site selection process as moribund and are calling on the government to rethink its approach. Suzuki Tatsujirō, a professor of nuclear engineering at Nagasaki University and former vice chair of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission, says that while the three sites joining the survey process is “notable,” he contends that the volunteer policy “places too heavy of a burden on the leaders of small, regional governments.” He suggests the government take a new line of action by appointing an independent body to propose between 50 and 100 sites and provide initiatives to inform and involve local stakeholders at each stage of the review process.

Professor Emeritus Imada Takatoshi of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, who headed the Science Council of Japan’s advisory committee on nuclear waste, asserts that the disposal debate needs to take place with the willful understanding of the immense timeline spanning tens of thousands of years. “We need to earnestly consider how our decisions now will be seen by future generations. I hope that with a national debate involving stakeholders at all levels we can forge a path forward.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Wind turbines spin along the coast of Suttsu, which was an early adopter of onshore wind power generation. © Matsumoto Sōichi.)