A Visit to the Katakai Fireworks: A Festival Deeply Rooted in the Local Community

Guide to Japan Society Culture Lifestyle History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Big Blasts in a Little Niigata Town

Niigata Prefecture on the Japan Sea coast is famous as the heart of the “Snow Country” and as a major center of rice cultivation (and the sake production that goes with it). In the summer months, the prefecture is also home to several well-known fireworks festivals. The biggest of all attracts more than 300,000 paying spectators every summer to the city of Nagaoka, just south of the prefectural capital. A remarkable 20,000 fireworks are launched in the course of this pyrotechnics extravaganza, including numerous super-sized “star mines” (in which strings of fireworks are fired off in quick succession) and the huge shō san-jaku-dama fireworks that explode from shells with a 90-centimeter diameter. Demand for tickets outstrips supply every year.

Not far from Nagaoka lies Katakai, a district in the north of the city of Ojiya consisting of around 1,400 households, or just 3,800 people. Despite its small size, every year Katakai holds a fireworks festival that is every bit as beloved as its big-city rival. Held in September, the Katakai Matsuri is one of the three major fireworks festivals of Niigata (still sometimes referred to by its old provincial name of Echigo), which between them cover most of the geographical extremes of this diverse prefecture: Kashiwazaki on the sea, Nagaoka on the river, and Katakai in the mountains.

The latest iteration of the Katakai festival took place on September 13 and 14, 2024. Over the course of the two days, more than 170,000 people packed the streets of the small community. Although the total number of fireworks launched—around 15,000—cannot compete with Nagaoka, Katakai’s mountain setting gives it an attraction that cannot be found anywhere else, as the boom of the fireworks echoes off the surrounding hillsides. The festival also boasts a Guinness World Record for the world’s largest firework, contained within a shell fully 120 centimeters in diameter and weighing in at 420 kilograms. These monster fireworks capture the heart of anyone who sees them and make the festival a highlight on the calendar for locals and visitors alike.

Katakai’s festival differs from most other major fireworks displays, which are run solely as entertainment and tourism purposes. Katakai’s festival remains uniquely rooted in the daily life of the local community. Individually and in groups, local residents donate money to sponsor fireworks as offerings to the local shrine and its kami. The festival is a rare surviving example of hōnō enka (fireworks offered to the gods), and dates back to Edo-period festivities to propitiate and entertain the kami.

The 1.2-meter firework launched on September 14 was the biggest blast of this year’s festivities. (Courtesy Ojiya municipal government)

Celebrating New Births and Long Lives

Members of the local community sponsor fireworks for various reasons: to celebrate a birth, wedding, or anniversary, to pray for good health or the prosperity of the family business, and in memory of a deceased relative. The sentiments and ideas that people bring to the festival are similar to those seen in the tradition of hatsu-mōde, when people throughout Japan visit a shrine for the first time in the new year.

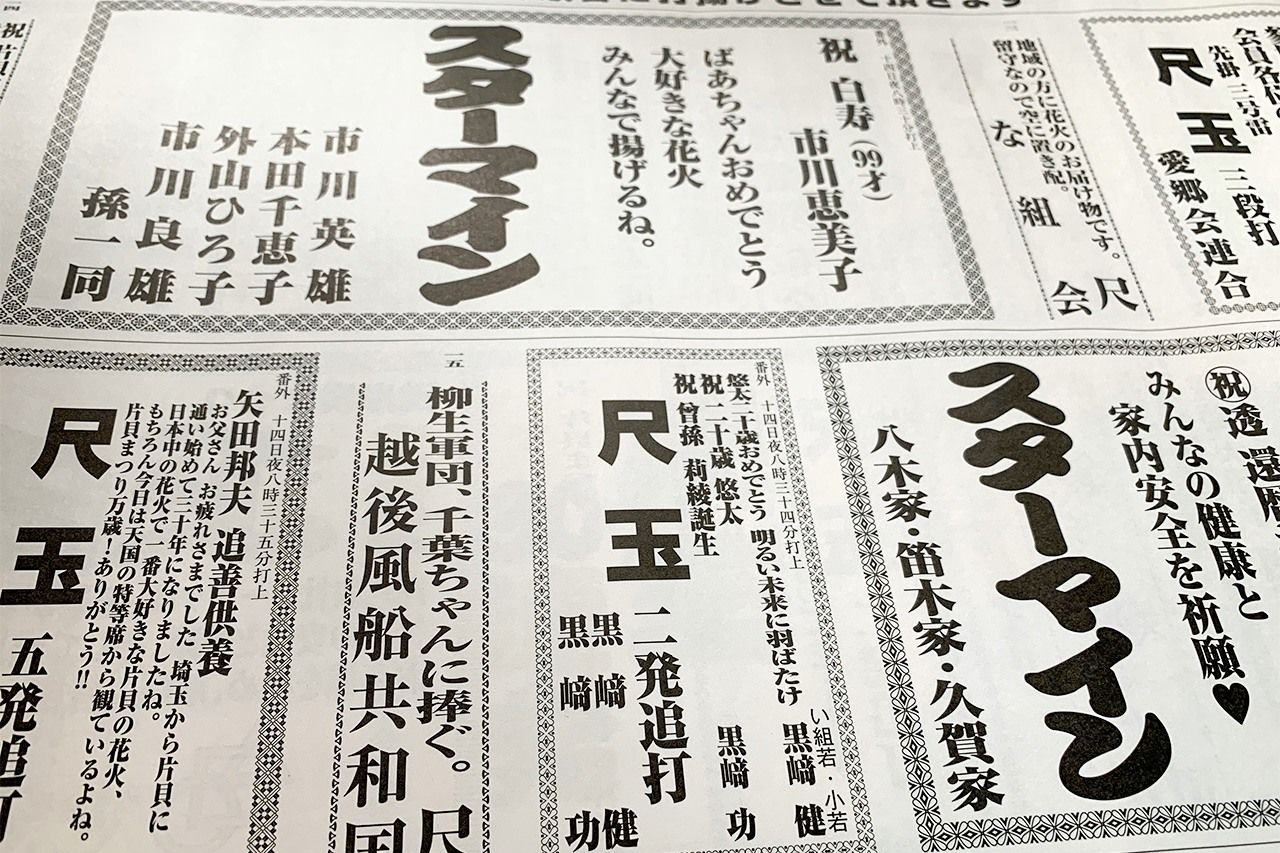

All these prayers, wishes, and messages are featured in a special publication called the fireworks banzuke. This printed program mirrors the format of a traditional sumo banzuke, which lists the names and rankings of the wrestlers and the order of bouts. At the Katakai festival, the banzuke provides details on the fireworks that will be launched in the course of the display, including timing, sponsor’s name, and the purpose or intention behind each firework.

The fireworks banzuke shares information on the full program with all visitors. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

A newspaper-style banzuke is also on sale for visitors to take home. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

Explosive congratulations to our first-born daughter, Ena.

Thank you for coming into the world so smoothly!

Nagahara Kai, 26, born and raised in Katakai, sponsored two large 30-centimeter shells (shakudama) this year to celebrate the birth of his first child, a baby girl. Kai’s parents sponsored fireworks when he was born, and he always knew he wanted to continue the tradition when he had children of his own. “Sponsoring a firework isn’t cheap,” he admits, “but it was definitely worth it. I’m thrilled to bits.”

Meanwhile, other residents celebrated a milestone at the opposite end of life’s journey:

Happy ninety-ninth birthday to Ichikawa Emiko.

Happy birthday, grandma!

Hope you enjoy this gift of your beloved fireworks from us all!

Seventy-nine-year-old Ichikawa Hideo and his three siblings clubbed together to launch a “star mine” firework for his mother, who marked her ninety-ninth birthday this year, together with her 10 grandchildren. Now living in an assisted living facility, his mother used to have a front-row seat for the fireworks every year in her younger days.

“Originally the plan was for the four siblings to sponsor a small firework,” Ichikawa says. “But then we reflected that there might not be too many years left. We decided to have the grandchildren contribute too. Together, we were able to sponsor one of the big ‘star mines’ and celebrate her big milestone with a bang.”

Ichikawa Hideo displays a photo of his mother, Emiko, with her entire family. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

The cost of sponsoring a shakudama is around ¥72,000. To qualify for special “off-list” status, which allows you to choose when your firework is launched, you need to be prepared to spend at least ¥143,000, equivalent to the cost of two shakudama fireworks. A “starburst” string of fireworks goes for more than ¥200,000. Some 300 individuals, companies, and organizations (including some from outside the region) paid to sponsor fireworks at this year’s festival.

School Year Groups and Bonds for Life

Reading through the messages on the banzuke, filed with gratitude and hopes for the future, it occurs to me that there can be few festivals anywhere that are so deeply intertwined with the lives of the local community as this one. This must surely be the happiest fireworks festival in the world.

Before each firework is launched, the sponsor’s name and message are announced—a moment of pride that is followed almost immediately by the thunderous boom. The sound reverberates across the hills as the fireworks bloom into dazzling patterns of color before scattering and fading in the night sky. For the sponsors, it’s a thrilling rollercoaster of emotions, experienced with all the senses. These moments are unique to the Katakai festival, and form memories that are cherished and prized for life.

Worshippers visit the Asahara Shrine during the festival. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

Festival seating is set up in an open field near the launch site. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

In Katakai, a strong sense of solidarity exists among children in the same school year. Year-group associations known as dōkyūkai are formed when students leave junior high school. Several years later, when they graduate from high school, young people start contributing to their dōkyūkai “fireworks savings fund,” which grows through annual contributions from its members. Each dōkyūkai launches its first fireworks in the year its members turn 20, symbolizing their transition into adulthood. Subsequent launches mark significant milestones, such as the yakudoshi years—traditionally believed to bring heightened risk of illness or misfortunes (33 for women, 42 for men)—as well as landmark birthdays like 50 and 60.

This year, the Ōkakai (Cherry Blossom Association) made up of young people turning 20 raised more than ¥5 million from members’ contributions, topped up with donations from family and friends. To celebrate their coming of age, they launched a breathtaking “star mine” firework, one of the festival’s highlights.

The “star mine” lights up the sky in honor of the newly minted adults. (Courtesy Ojiya municipal government)

As well as the “star mine” sponsored by the young people themselves, a special 120-centimeter shell was launched in honor of the town’s latest cohort of adults—proudly sponsored by “the whole population of Katakai.” This has become an annual tradition. This year’s celebration dazzled with spectacular patterns as the mega-firework burst some 800 meters above the ground, its blast expanding to an incredible 800 meters across the nighttime sky.

Another cherished Katakai custom is the special firework organized by the dōyūkai for people celebrating their sixtieth birthdays, marking the completion of an entire cycle of the East Asian zodiac. This year, the Sazanami-kai (“Wave Association”) marked its members’ milestone birthdays by sponsoring a huge “star mine” costing more than ¥10 million. This was the largest firework in the festival’s history, producing booms and reverberations that lasted for over five minutes.

For the people of Katakai, the festival is not just an event to watch but something to take part in. There are even tales of passionate festival enthusiasts who left jobs in other towns to return and help with the preparations for the festival. Everyone is eager to play their part. And as soon as one year’s festival ends, planning for the next one begins.

“Never Take a Bride from Katakai”

Spending lavishly on fleeting moments of pleasure and expressing the self through nonchalant displays of sprezzatura align closely with the Edo period aesthetic of iki—often translated as “quiet elegance” or “effortless chic.” Katakai is perhaps one of the few places in Japan where this culture endures to the present day. The town’s love for its festival and the people’s readiness to spend whatever it takes to create the most awe-inspiring fireworks are well known throughout the region. For centuries, neighboring towns have regarded Katakai’s extravagant devotion to fireworks with a mixture of wonder and disapproval. An old adage even warned: “Never take a bride from Katakai, and don’t let your daughter marry into a family from there either.”

What explains the belief that fireworks can pacify the spirits of the dead and ward off disease? The association reportedly dates back to 1733, in the mid–Edo Period, when the Suijin festival was held on the Sumida River, a vital artery of life in Edo (now Tokyo). In the wake of a major famine and epidemic, the shōgun of the time, Tokugawa Yoshimune, organized a magnificent firework display to bring peace to the spirits of the dead. This event is thought to have inspired the tradition of offering fireworks as part of religious and ceremonial practices over the course of the year.

In Katakai itself, a local almanac kept by a village official (shōya) notes that in 1802 “diverse fireworks were launched, of which not a single piece failed to take fire.” By this point at the latest, fireworks seem to have become an integral part of the town’s culture.

A banzuke survives from 1867. Much like today’s banzuke, it lists the type and size of each firework, along with the name of the sponsor.

The origins of Katakai’s fireworks industry are tied to its historical status as a town that was directly administered by the bakufu, or shogunate. The town would have been home to a range of skilled craftsmen and artisans, including smiths, dyers, and carpenters, as well as specialists in firearms and gunpowder. These artisans started to produce pyrotechnics, honing their skills over time as they competed to create the most spectacular and beautiful displays.

Today, these proud traditions are kept alive by companies like Katakai Fireworks, Co., which continues to produce the dazzling pyrotechnics that light up the skies above Katakai at the end of every summer.

A worker at Katakai Fireworks makes the “stars” that glitter after the detonation of a major firework. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

Multiple layers of paper are applied to the outside of each firework to make them sturdier for launch. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

The massive launch tubes used for the 90- and 120-centimeter behemoths. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

A Rite of Passage

Traditional ceremonies are another essential element of the Katakai festival. Two of the most significant are the tama-okuri and tsutsu-hiki processions.

In the tama-okuri ceremony, fireworks are formally presented at the Asahara Shrine. (Tama, meaning “jewel” or “ball,” is the word used to describe the round, onion-like firework shells in their pristine, unexploded form.) The tradition dates back to the early Meiji era (1868–1912), when young men would visit each household, collecting fireworks in boxes to present to the shrine. Although the actual fireworks are no longer brought to the shrine, young people from the town’s six divisions still pull festival floats through the streets before converging on the shrine. And it’s not just young people: The sight of people of all ages filling the streets with energy and excitement sets the tone as the opening day of the festival approaches.

The atmosphere is enlivened further by the kiyari-uta songs sung by participants as they pull the floats, accompanied by festival music played on flutes and taiko drums.

Another important ceremony is the tsutsu-hiki, during which the launch tubes (tsutsu) for the huge firework shells are carried through the town. This ritual serves as a prayer for the safe and successful launch of the fireworks during the festival.

Procession participants play music as they walk through town. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

Young people take part in the tsutsu-hiki ceremony. (Courtesy Ojiya municipal government)

Fireworks viewed from the Asahara Shrine. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

An important part of the tama-okuri ceremonies is the seijin tama-okuri, in which young people who have come of age during the year walk their way through the six districts. This important rite of passage marks their recognition as full adult members of the community for the first time. At the border between each district, their path is blocked by the district chief. Without the chief’s permission, they cannot pass into the next district. The district chiefs are their senpai, senior figures who passed through the same trials and rites of passage themselves in earlier years.

The criteria for granting the permission are simple: are the young people doing enough to enliven the festival? The settai-yaku (entertainment officer) of the dōkyūkai pours sake for the district chief. Permission is granted when the district leader accepts the drink. But this can take some time.

“Please! Let us through!”

“You have to do it properly! Make more noise! Let’s see more energy from you!”

These exchanges can continue for nearly an hour, and even after permission is given to pass, the young people still have to engage go through the same routine with the district chief at the next boundary point. It is normally around eight in the evening by the time they finally reach the Asahara Shrine.

The community’s 20-year-olds in the seijin tama-okuri. (Courtesy Ojiya municipal government)

After passing through the seijin tama-okuri, many young people join the waka-rengō (young people’s association), which plays a central role in running the Katakai festival. Nagahara Kai, who this year sponsored a firework to celebrate the birth of his first daughter, served as the leader of the waka-rengō until last year.

“You’re responsible for ensuring that the whole festival runs smoothly, so you’re super-stressed the whole time and you can’t relax or enjoy the fireworks. Last year was particularly difficult. My wife was due to give birth any moment, and I was so preoccupied I didn’t know if I was coming or going. Our daughter was born two days after the festival. This year I was able to relax and enjoy the fireworks properly for the first time in ages.”

An Enduring Image of “Old Japan”

In Katakai, elementary and junior high school children take part in the tama-okuri processions around the districts where they live and go to school. Once the midsummer Obon holidays are over, it’s common for children to spend much of their free time practicing the festival music. Experiences like this, starting in childhood, mean that for many people in the community, the festival and preparations for it become a lifelong part of everyday life.

Youngsters also play their part in the tama-okuri. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

During the two days of the festival, more than 200 floats and stalls line the streets, transforming the normally quiet town into a mass of heaving energy and life. “As festival time approaches, everyone starts to get excited. You can hardly sit still; there’s so much anticipation in the air. It’s the one time everyone looks forward to most,” says 74-year-old Yoshiwara Masayuki with a smile.

Festival stalls line the lively streets. (© Shinohara Tadashi)

In many areas around the country, this sense of local community is fading as a result of increasing urbanization, an aging population, and declining birthrates. The traditions of the Katakai festival have endured for so long because the festival and its ceremonies are so deeply rooted in the lives of local people. While distinctive traditions and rites of passage are lost in many other regions, in Katakai even a slightly wild tradition like the seijin tama-okuri has been passed on unchanged and untamed into the modern age.

Even in Katakai, of course, the number of young people is declining. During the postwar baby boom, local middle schools had nearly 200 children in each graduating class—the most recent number was just 26. As the number of people in each age cohort shrinks, a larger burden is placed on each person to contribute to the fireworks funds, and smaller numbers also affect the community’s ability to keep the tama-okuri and other traditions alive. Additionally, some people choose not to join their age group’s dōkyūkai. In an era of increasing individualism, it is not surprising that some people are turned off by the “village community” aspects of traditional cultural practices.

It is impossible to predict what the future holds for Katakai or how the community will evolve. But if there is such a thing as a pristine, unspoiled version of traditional Japanese character and culture, this small town in the hills of Niigata is one of the few places in the country where it can still be found intact.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo courtesy of Ojiya municipal government.)