Takoyaki Sushi? Overseas Eateries Show Versatility of Japanese Food

Guide to Japan Society Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japanese Cuisine Reinterpreted

I visited the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur in spring 2024 to explore the local dining scene. A diverse nation, Malaysia boasts an abundance of dining choices, ranging from native cuisine to Indian dishes to a wide range of regional Chinese flavors brought by transplants from places like Fukien, Hainan, and Chaozhou. Then there is Nyonya cuisine, a fusion of Chinese, Malaysian, and Southeast Asian cooking that developed through the mixing of immigrant communities. Foodie or not, the extraordinarily broad and complex food culture is rewarding to explore.

Japanese food is also popular, although it often takes on a unique local twist. At a cooked food market on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur, for instance, the shop Tokyo Corner serves up unique fare like a bowl of udon topped with a crispy chicken katsu, a combination that would raise eyebrows in Japan.

The menu at Tokyo Corner in Kuala Lumpur offers unique takes on Japanese food. (© Himeda Konatsu)

Denizens of the city have a taste for sushi, particularly gunkanmaki—seaweed wrapped around vinegared rice and topped with various morsels—and inarizushi, which is made from sweetened fried tofu stuffed with rice and other fillings. Shops with display refrigerators packed with colorful sushi rolls and creative inari can be found in the basement-level food markets of many department stores, drawing crowds of hungry locals in the evenings who eagerly choose among the selections on their way home.

Among the distinct offerings are sushi rolls stuffed with eel and cheese and nigirizushi featuring cheese as the lone neta. But the hands-down favorite is gunkanmaki topped with takoyaki, a savory octopus-dumpling that is typically enjoyed as a snack on its own.

Takoyaki sushi is a fusion of two Japanese dishes. (© Himeda Konatsu)

Conveyor belt sushi shops are also popular, and local chain Sushi King is always hopping. Here too, gunkanmaki and inari featuring takoyaki roll along the conveyor belt. There is also flavored minced chicken called torisoboro and seaweed salad made with wakame. Japanese founder Konishi Fumihiko launched the chain in 1995, and he has since opened shops in over 100 locations across Malaysia. While Sushi King draws mixed reviews from Japanese residents, who consider it a poor imitation of the real thing, it remains a popular go-to spot for locals wanting to get their sushi fix.

Diners pack a Sushi King outlet in Kuala Lumpur. (© Himeda Konatsu)

The King of Faux Japanese

Reinterpreting sushi is certainly not new. In fact, the California roll could well be called the first “faux Japanese” dish. Born on the US West Coast in the 1970s, it is a savory makizushi packed with real or imitation crab meat, avocado, cucumber, and mayonnaise.

A variety of sushi rolls in a display refrigerator at a supermarket in New York. (Photographed in March 2021; © Levine Roberts/Newscom/Kyōdō)

An engineer from Florida I met in Frankfurt in 2023 mentioned that sushi rolls are very popular in the United States, saying that “I often go to sushi shops near my home with friends or family, and we usually order more rolls than nigiri.” A particular favorite is something called a dragon roll.

A twist on the California roll, it is made with grilled eel—a standard filling even in Japan—or shrimp tempura and topped with avocado slices arranged to look like the scales of a dragon. Also going by the name caterpillar roll because of its length and green color, it is as eye-catching as it is delicious.

I enjoyed a dragon roll in Bangkok in 2019, but a friend from Singapore told me that the dish has been available in the city since the 1980s. The California roll has inspired other sushi interpretations that have quickly spread worldwide, creating a wide array of fusions in the American style. By contrast, the availability of traditional Edomae sushi overseas is a relatively recent development.

A dragon roll at a restaurant in Bangkok. (© Himeda Konatsu)

I understand that in Brazil, they even have a sweet variation of the California roll called monkey roll sushi that is made with fruits like banana or mango. It is difficult to imagine a Japanese sushi chef coming up with something akin to desert sushi.

Japanese Food in Europe

Another Japanese favorite that has been reinterpreted abroad is ramen, which could well be called Japan’s national food. The noodle dish has Chinese roots, but it has developed its own character in Japan and has become a fast favorite across Asia and even as far away as Europe.

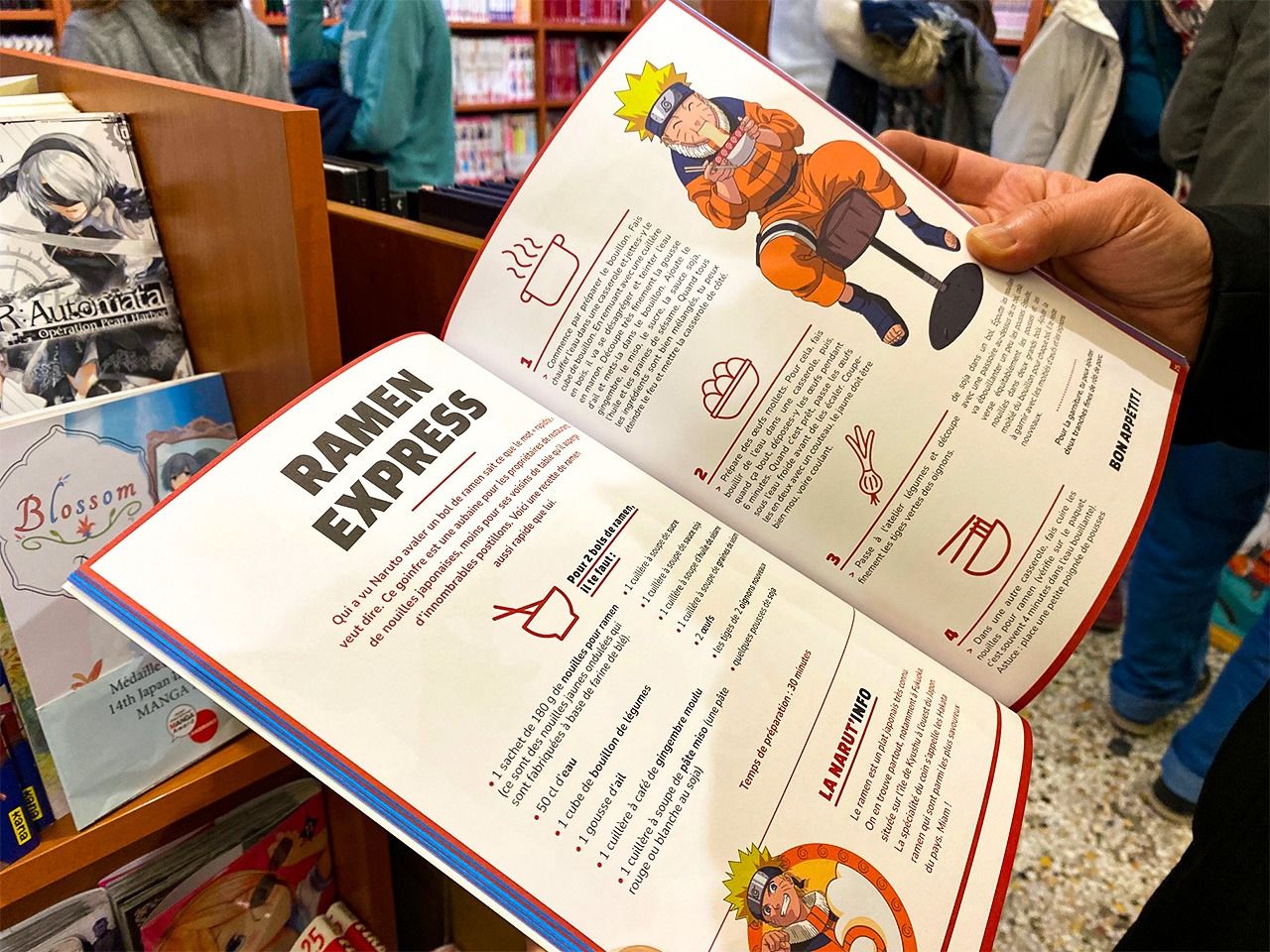

In the autumn of 2022, I attended an exhibit showcasing the manga Naruto held at the Belgian Comic Art Museum in Brussels. The event attracted guests of all ages, and I spoke with a Canadian visitor who told me that anime has introduced fans to foods like ramen, sushi, and curry, showing how the medium has helped fuel the global boom in Japanese cuisine.

I saw an example of this in the summer of 2023 while visiting a comic market held as part of the Frankfurter Book Fair. Outside the venue, visitors lined up in front of a ramen food truck sporting the ramen-loving main character from Naruto.

A book on ramen produced in a tie-up with the Belgian Comic Art Museum features ramen-obsessed Naruto Uzumaki. (© Himeda Konatsu)

A Naruto-themed ramen food truck draws a line of peckish attendees outside a comic market in Germany. (© Segawa Midori)

Frankfurt has seen a real upsurge in Japanese ramen over the past few years. One shop in particular, Muku run by Japanese owner Yamamoto Shinichi, has won a devote following in the city and was even invited to offer up it noodles at a special “reverse import ramen” event at the Yokohama Ramen Museum. Muku offers an authentically crafted, umami-rich broth that locals enjoy pairing with sake and wine.

Not all shops are as dedicated to serving up genuine Japanese flavor, though. One Japanese resident of Frankfurt visiting the comic market lamented that ramen often looks legitimate, but hides a broth lacking dashi or that is cloyingly sweet, declaring that “it’s a far cry from anything you’d get in Japan.”

On a recent visit to Italy, I came across a shop next to Rome’s Termini Station advertising something called “gyōza ramen.” The shop was named Wagamama, and at first glance I was happy to see what I thought was a familiar pairing of potstickers and Japanese ramen, only to discover on closer inspections that it was nothing of the sort.

First of all, the gyōza were not served alongside the ramen as in Japan, but were setting right on top of the noodles. The flavor was equally startling. The menu described the dish as noodles topped with gyōza, grilled bok choy, and cilantro, with a side of sambal paste, soy sauce, chili oil, and sesame dipping sauce. The use of sambal, a Malaysian condiment, and other ingredients certainly infused the dish with a distinct “Asian” flavor, but as ramen, it was something all its own.

Wagamama opened its first location in London in 1992 and now has 150 branches in 22 countries. For Japanese living in Italy, though, its flavors have proved to be a hard sell.

A menu outside a shop in Rome advertises gyōza ramen. (© Himeda Konatsu)

Tanaka Toshiyuki, who worked as a sushi chef in Italy until 2016 and is now at high-class Japanese restaurant Sushi Kinmedai in Kuala Lumpur, says that authenticity varies greatly when it comes to Japanese cuisine in Europe. “Compared to Paris, where Japanese food has become very popular,” he explains, “there is little differentiation made between Japanese and Chinese cuisine in Italy. People tend to lump all Asian food together.”

Tanaka points out that a lack of access to authentic ingredients can make it difficult for shop to recreate Japanese flavors. “EU import regulations are very strict and certain items are nearly impossible to find, making it extremely challenging for restaurants to offer something genuine.”

Japan’s Own Faux Chinese

How easy is if for international diners to appreciate the true, authentic flavors of Japan? Sociologist Kurasawa Sai, who spent time in the early 2010s teaching at the University of Dhaka in Bangladesh, shares this anecdote:

“The local Japanese Embassy wanted to showcase Japanese food culture, so they invited around 50 local dignitaries to a Japanese-style dinner. The dishes were mostly flavored with dashi broth, and the guests were very vocal about how delicious and healthy the food was. In truth, though, the guest’s impressions were a little different. Bangladesh cooking relies heavily on spices, and I heard directly from some attendees that they found the flavor to be somewhat lacking.”

For Japanese, there is a tendency to look down on “faux Japanese food,” but this ignores the fact that Japan itself is a master of taking the cuisine of nations and twisting it to fit Japanese palates.

When asked about Chinese food, for instance, many Japanese will immediately picture dishes like tenshinhan—a crab omelet over rice—or Chūkadon, a Chinese-style rice bowl topped with stir-fried meat, seafood, and vegetables. But a Chinese person will tell you that no such dishes exist in China. Even so-called authentic Chinese cuisine in Japan can seem foreign to a person accustomed to the real thing. Just the other day, a Chinese businessperson visiting Tokyo declared to me how the ingredients and flavors of typical fare like babaocai (eight treasure vegetables) or twice cooked pork served in Japan are completely different from what is offered in China.

Faux Japanese cuisine overseas might be a far cry from the real thing and cause some to grumble about giving the wrong impression of what Japanese food actually is. But on the flip side, when Japanese dishes are reinterpreted to fit local tastes, it results in intercultural exchange that is tangible and tasty. Taking an open-minded approach will provide important clues for creating new and unique strategies for inbound tourism and for developing international food businesses in Japan and further afield.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: © Himeda Konatsu.)