Hoi An, Vietnam: Preserving Unique Streetscapes with Cooperation from Japan

Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Restored Bridge Symbolizes Centuries of Ties

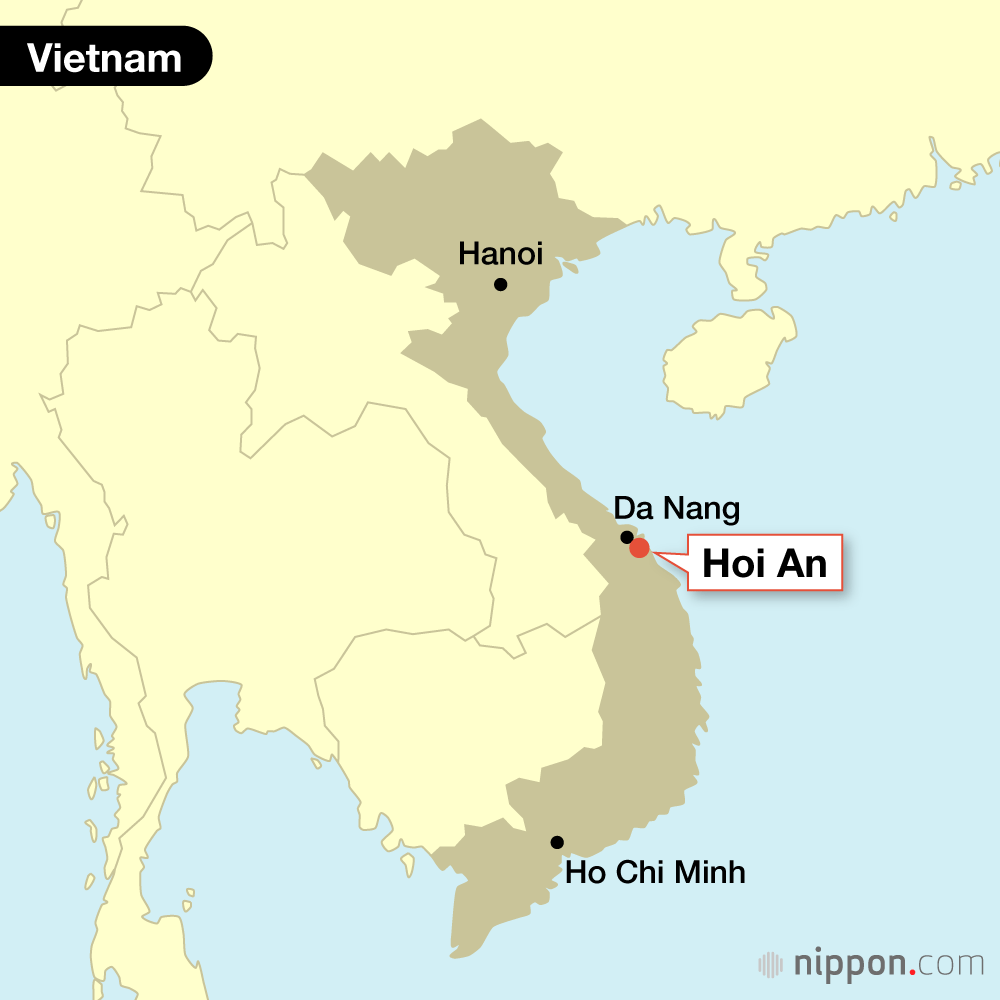

Hoi An is approximately 30 kilometers south of Vietnam’s fifth biggest city, Da Nang. The city is home to a bridge commonly referred to as the “Japanese Bridge.” The famous landmark, with its beautiful roof and entrance decorations, features on Vietnam’s 20,000 dong banknote, and was registered as a world heritage site in 1999. The bridge’s official name is Cau Lai Vien, the “bridge for people from afar.“

Cau Lai Vien, the “Japanese Bridge,” is a symbol of the world-heritage-listed Hoi An old city. Since its restoration, the surrounding area has been packed with tourists. (© Tomoda Hiromichi)

A year and a half of restoration work was completed in August 2024, when the bridge was unveiled to reveal its fresh appearance. A ceremony was held marking the completion of construction, which coincided with Hoi An’s Japanese Festival, held each August and now in its twentieth year. The bridge, considered a symbol of Japan-Vietnam relations, has again become a key attraction for the town since its restoration.

The work was conducted with the cooperation of experts from the Japanese Government, Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, and the Japan International Cooperation Agency. I was sent to Vietnam by JICA in August 2022 to provide expert advice on the work, which was a milestone in our cooperation for townscape preservation.

Interior of the “Japanese Bridge,” showing its timber structure. (© Tomoda Hiromichi)

The bridge linked the old Japanese and Chinese quarters. Over its history, the bridge has been rebuilt numerous times, following damage from Hoi An’s frequent floods.

Repaired pillars and beams are reassembled during work on the “Japanese Bridge.” (© JICA)

Restoration on the bridge’s roof sections included intricate decorative paintwork. (© JICA)

History of the Japanese Quarter and Trade with Vietnam

The bridge was first constructed in 1593, funded by Japanese merchants, and is believed to have been rebuilt in its current form in 1817.

Hoi An prospered during the so-called Age of Exploration, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as a transit port, attracting Chinese, Portuguese, and Dutch trading ships. After the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368–1644) introduced a ban on maritime trade with Japan, wealthy Japanese merchants began independent trade with “red seal ships,” which were licensed to operate by the Tokugawa shogunate. This resulted in the growth of a community of Japanese traders on the east side of the Japanese Bridge. The Japantown remained in existence until the mid-seventeenth century, when Japan’s ruling shogunate introduced its own national isolation policy.

Japanese Support for Townscape Preservation

As Vietnam continues its economic growth, it is becoming less dependent on official development assistance. In the area of cultural preservation, it is no longer reliant on unilateral aid from Japan. According to media reports, the restoration work on the bridge cost a total of 20.2 billion dong, contributed by agencies of Quảng Nam Province and Hoi An City, with just a small amount of private Japanese support. The Japanese and Vietnamese involved in the project exchanged opinions as equals.

For Hoi An, the over 30 years of collaboration with Japan have special significance. The city sought expertise from Japan, with its depth of experience in preservation of temples and other wooden structures, due to the many wooden buildings in its historic district.

In the early 1990s, many of the aging residential, public and religious structures in the city’s old district were considered in danger of collapse. But it was crucial to first gain residents’ understanding of the importance of maintenance and preservation.

Hoi An in 1997, with the entrance to the Japanese Bridge visible in the background. (© Tomoda Hiromichi)

From 1993, a Japanese team comprising members from schools including Shōwa Women’s University and other experts were tasked with providing technical support for townscape preservation, under the direction of Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs. The team, which I was leading at the time, provided technical expertise, information, and training, in a five-stage process.

Initially, the team conducted a study of the historical background, the structure of the buildings, and their use by residents. The next step was to gain consensus to accept Japanese cooperation for preservation of cultural heritage. Following this, discussions were held with property owners and the government regarding the preservation of historical buildings. Thereafter, mechanisms were devised to facilitate the provision of Japanese donations and grants to Vietnamese residents’ organizations. Finally, Japanese specialists were brought in to share their expertise. Meanwhile, Vietnam concurrently advanced efforts to gain world heritage registration for the area.

Considerable effort was made to retain original materials by sharing techniques with the Vietnamese working on the project, including kintsugi (mending breakages with urushi lacquer and powdered gold). Members from the Vietnamese side were also invited to Japan to study various techniques at university.

Central Hoi An in 1995, when there were far fewer tourists. (© Tomoda Hiromichi)

Respecting the Dignity of Vietnamese People

Great care was taken each step of the way to avoid any trouble that might arise from such close involvement by Japan, as an outsider. For this reason, we endeavored to pay utmost respect to the autonomy and dignity of the Vietnamese, and to the processes. From September 1996, Hoi An issued a municipal order prohibiting cultural restoration work without Japanese technical guidance to prevent unregulated reconstruction and in an effort to improve local expertise. In this way, the city quickly established autonomous systems for preserving its townscape.

Tourists enjoy shopping and dining in Hoi An’s historical precinct. (© Tomoda Hiromichi)

In the past, Japan had been one of a number of countries involved in restoration work—on Egyptian pyramids and at Angkor Wat in Cambodia, for instance—but this was the first case of cooperative efforts begun only with Japan and proceeding under Japanese direction. There was a strong sense of Japan’s deep involvement, which was warmly welcomed by the city’s people thanks to Japan’s deep experience in restoring and preserving its own ancient wooden structures, including the temples Hōryūji (the world’s largest all-wood structure) and Tōdaiji (the oldest).

Following Hoi An’s world heritage listing, assistance for the city was accepted from other countries in addition to Japan.

Birdseye view of Hoi An’s world heritage listed precinct. (© Pixta)

Restoration Leads to a Tourism Boom

Prior to Hoi An’s world heritage listing in 1999, around 200,000 tourists visited the city annually. In 2001, the number doubled to 400,000, and has continued to soar, reaching 1.5 million in 2011 and 5 million in 2018. The city expects to exceed this number in 2024. Its successful development as a tourism destination has been all thanks to the efforts made in restoring the historic town.

Hoi An initially held events, such as its Lantern Festival, roughly once a month, but now there are daily night markets and the town is constantly abuzz with visitors.

Hoi An lit by colorful lanterns at night. (© Tomoda Hiromichi)

One factor in Hoi An’s popularity, in addition to its provision of tourist-friendly facilities, is surely its welcoming attitude, perhaps due to the city’s history of hosting foreign visitors since the Age of Exploration.

Support Opportunities for Diverse Interaction

Initiatives are now being launched to facilitate sustained reciprocal study exchanges between Hoi An and municipalities in Japan. In the seventeenth century, willow-leaf pattern woven cloth imported from Hoi An to Matsusaka in modern-day Mie Prefecture inspired the development of striped cloth known as Matsusaka momen. Matsusaka’s merchant families who owed their fortunes to Matsusaka momen, such as Mitsui, Ozu, Kokubu, and Hasegawa, set up businesses in Nihonbashi, Tokyo. The Mitsui family business grew into the Mitsui business empire. Thanks to these historical links, both Matsusaka and Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district have now established ties with Hoi An.

Araki Sōtarō, who operated a trading vessel in the late 1500s, married a Vietnamese princess known in Japanese as Aniō, who accompanied him to Nagasaki. The procession to welcome her is re-created annually at the Nagasaki Kunchi Festival, leading to the launch of exchanges between the two cities today. Other relationships have been established including with the Iwami silver mine, also listed as world heritage, in Shimane Prefecture, which once exported silver via Hoi An to as far away as Europe, as well as Sakai, Osaka, which engaged in maritime trade with Hoi An, and Kyoto’s Nishijin district, which is helping the city to revive silk production.

In 2023, an opera entitled Princess Aniō was produced to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Vietnam and Japan. It was staged at Shōwa Women’s University in Tokyo, in Yokohama, and in Vietnam. The university also hosted an exhibition of Hoi An’s “Japanese Bridge,” which included a 1/10 scale model of the bridge and a virtual reproduction of the townscape using VR Chat.

Japan’s Prime Minister Abe Shinzō (second from right in bottom row) and Vietnam’s Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc (third from right) at the November 2017 unveiling of a replica Japanese trade ship presented as a gift from Nagasaki Prefecture. (© Jiji)

Visits to Hoi An by Key Japanese Persons

A wide range of people have been involved in Japan-Vietnam relations, often with Hoi An as the focus.

During a state visit in 2007, Japan’s Emperor Akihito (now emperor emeritus), expressed his pleasure at learning about the collaborative work between Japan and Vietnam that led to the restoration of the Hoi An townscape and its traditional wooden structures. Crown Prince Naruhito (now emperor) also visited in 2009, and Prince Akishino visited in 2023. In 2017, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō visited the city.

Japan-Vietnam relations, centered on economic activities, are currently booming, and hopefully Vietnamese people will long remember the steady cooperation that Japan has provided by trying to stand in Vietnamese shoes.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Hoi An’s streetscape preserved with cooperation from Japan. © Tomoda Hiromichi.)