The Kimono Hijab: A Fashion Melding of Japanese and Islamic Culture

Culture Fashion- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Shared Eye for Beauty

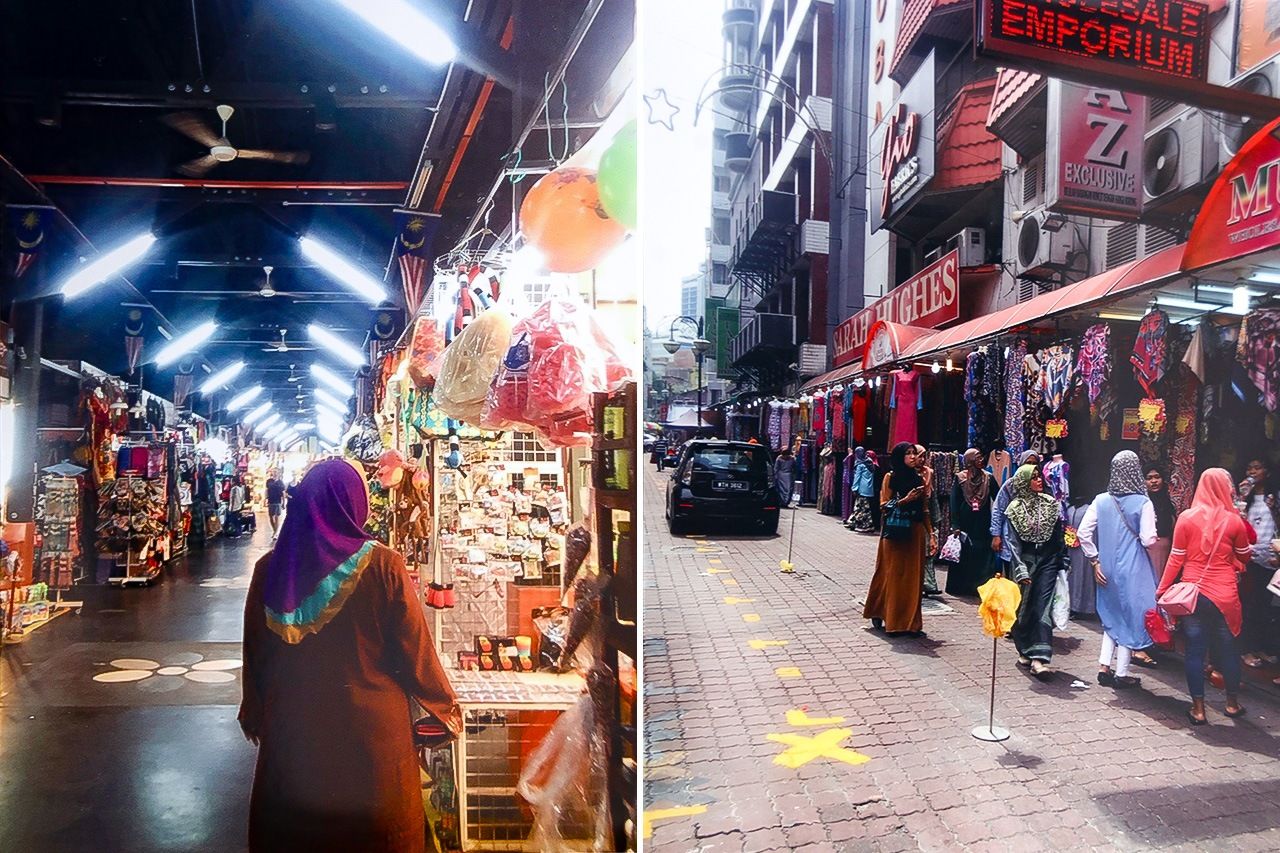

Visiting Malaysia for the first time in 2017, Kobayashi Kaori took in the kaleidoscope of sights, sounds, and flavors of the country. She found the aspects of Islamic culture that she encountered new and exciting and was particularly taken by the array of hijabs to be found. She had assumed the headscarves to be characterless affairs, worn out of religious duty, but everywhere she looked her eyes found vibrant colors and intricate designs. She was enchanted by the beauty.

Kobayashi gazes at the bustling nightlife during a trip to Malaysia. (Courtesy of Kobayashi Kaori)

Admiring the different types of hijab women wore, Kobayashi felt a kindred connection. She had studied Japanese popular culture of the early twentieth century in university, through which she had developed a fondness for the bold designs and bright colors of kimonos from the period. “I recognized in the hijabs a shared expression of beauty,” she recounts. Although inexperienced in the world of Japan’s traditional garb, she had an overwhelming urge to try her hand at making the headscarves using material from vintage kimonos.

Kobayashi felt an instant affinity for the stylishness of the hijab she saw in Malaysia. (© Kobayashi Kaori)

Sewing Machine Adventures

Kobayashi was determined to have a go at making a hijab, even declaring to her startled husband that she was going to buy a sewing machine once back in Japan. Her first attempts, made from her grandmother’s ancient kimono, involved stitching a strip of the silk material onto a backing of thin cloth she had purchased at a handicraft store. “It was a lot of trial and error,” she says. She offered these early creations on an online flea market and managed to sell one or two a month.

Kobayashi embarked on making hijabs with very little knowledge of Islam to build on. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Dipping her toes in the hijab-making business, Kobayashi was naturally curious to learn more about the history and culture surrounding the head coverings, and by extension Islam, a religion she knew mostly in name only. She connected on social media with Muslims from different countries, who kindly answered her questions about hijabs.

In contrast to her burgeoning curiosity about Islam, many in Kobayashi’s circle of friends in Japan were suspicious of the faith owing to news of terrorist bombings and other violence perpetrated by Islamic extremist groups around the world. “When I said I wanted to visit a mosque,” she recounts, “some people tried to dissuade me on the grounds that it was dangerous.” This sort of reaction from those close to her was hard to deal with, she recalls.

Overcoming Perceptions

Kobayashi understood the lure of stereotypes, but she had learned firsthand while accompanying her husband to Shanghai in 2012 to not be swayed by perceptions. The pair were in the city during a time of heightened anti-Japanese sentiment in the media and elsewhere in China, but they found a far different situation from what was being broadcast on the evening news. Rather than being confronted by animosity at every turn, they were impressed by the warmth and respect locals showed.

Sewing her hijab, Kobayashi realized that the negative impressions of Muslims she and others clung to stemmed from an unfamiliarity with Islam. Overcoming these biases, she knew, required acknowledging one’s ignorance and confronting it head on.

However, she admits that she was uncertain whether she was taking the right approach. “I’d been impressed by the hijab for both its religious significance and as a fashion statement,” she explains. “I’m not especially religious and I was wary of misrepresenting Islam. I questioned whether it was appropriate for me to make a business out of something so significant to Muslims.”

Her Muslim associated listened to her concerns and encouraged to keep going, telling her that “hijabs belong to everyone.” Moved by such a broad-minded response, Kobayashi forged ahead with renewed confidence while growing more determined to dispel lingering Japanese stereotypes of Muslims.

Thinking in Terms of Casual Fashion

The hijabs Kobayashi saw in Malaysia were primarily made of chiffon, a light, breathable material suited to the humid climate that was worn in a lovely, flowing manner. In Japan, two types of silk gauze, ro and sha, with similar cooling properties to chiffon were typically selected for kimono use in Japan’s humid summers. Ro was generally for more formal attire and the sha for everyday wear.

The sha silk gauze used to make kimonos is sheer and permeable, cooling the wearer. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Kimonos are seldom worn today even in their home country, though. As a fan of the native dress, Kobayashi felt that repurposing antique kimono fabric for hijabs would offer people a casual way to enjoy the beautiful designs of the garments. Using the kimono cloth alone proved too weighty for the head coverings, but after some thought, she struck on the idea of combining it with chiffon. “I was confident it would make for hijabs that are light and easy to wear.”

Settling on sha gauze, which has a simple weave and is more suited for everyday use, she tweaked her design, coming up with a casual design for her kimono hijabs that she felt would appeal to Muslim customers. Nine short months after her visiting Malaysia, Kobayashi launched her brand Xiaxia Hijab Japan, using the kanji character for sha (紗) in the name.

A creation by Xiaxia Hijab Japan alongside Kobayashi’s certification as a dealer in second-hand clothing, which she needed to work with vintage kimonos. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Fashion Upcycling

Offering her creations online, Kobayashi steadily built her brand. The feedback she received from customers was positive, with many who bought her hijabs expressing gratitude for her efforts. She was pleased to discover that the colors and designs of Japan’s traditional wear resonated with people overseas, but as not every pattern was appropriate, she had to develop an eye for those that appealed to her customer base. “I spent a lot of time working out what would fly and what wouldn’t.”

Pink is the most popular color for Kobayashi’s hijabs. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Kobayashi found when visiting second-hand shops dealing in vintage kimono that the colors and designs suited to hijabs tended to differ from the styles that Japanese customers preferred, providing her an ample selection to choose from. She says that shop owners were glad to see the antique items get a second life, keeping them in people’s wardrobes and out of dumpsters.

Many of the kimonos Kobayashi buys have bright, showy designs. (© Hanai Tomoko)

One-of-a-Kind Items

The first step in creating a kimono hijab is preparing the material. Kimonos consist of roughly nine separate pieces—collar, sleeves, outer shell, inner lining, and such—that must be unstitched. Kobayashi says that only the outer fabric is used to make hijab.

Removing all the stitching from a kimono reveals different-sized rectangular pieces of fabric. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Next, the pieces are handwashed in water—to protect the delicate silk fabric, detergent is only used for heavily soiled or stained items—hung out to dry, and then rewashed before being ironed. Any damaged portions are discarded. Most kimonos will yield enough fabric for five to ten hijabs. Kobayashi says that she is constantly tweaking her original designs as she makes her hijabs from a steady flow of antique Japanese wear, making each of them a one-of-a-kind item.

Kobayashi says the most enjoyable part of the process is coming up with designs for hijabs. (© Hanai Tomoko)

It takes concentration and skill to sew the different fabrics together. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Enjoying Breakout Success

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020 brought a downturn in business as tourism from overseas halted and residents of Japan were asked to stay home. Kobayashi became ill herself, but says that she was determined to continue making hijabs “as long as they bring joy to people.” In May 2022, she opened a shop in Tama in western Tokyo, her first brick-and-mortar location. When foreign visitors began to return in 2023, she also started offering her hijabs at a tourist information facility in Harajuku. People really started to take notice when the facility shared a video on social media, leading to Xiaxia’s big break. “The video went up on December 30,” Kobayashi recounts. “By January 2, the shop in Harajuku had completely sold out. It was the busiest I’d ever been.”

Kobayashi’s husband Keita recalls the hectic period: “She hardly slept until the following spring rolled around.” Keita, who works for a firm in the information industry, supports his wife in her endeavor, including by tapping into his PR experience to help promote Xiaxia’s offerings.

Kobayashi’s husband Keita. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Making a Difference

The company celebrated its seventh anniversary in 2024 and has continued to expand its physical presence. In March Kobayashi started offering her hijabs at the new tourist facility next to Toyosu Market in Tokyo, and in May she opened another location in Asakusa at the flagship store of Halal-Ya, a firm offering Muslim-friendly souvenirs and other services. Her online shop has also continued to grow, and Kobayashi now creates some 100 hijabs a month to keep up with demand. By necessity she outsources some aspects of the production process, but she continues to carry out the majority of the work herself, including the crucial tasks of shopping for vintage kimonos and chiffon and designing the pieces.

Kobayashi (right) and an Arabic-language editor from Nippon.com model Xiaxia hijabs. (© Hanai Tomoko)

As might be expected, the clientele at Xiaxia’s shops are predominantly Muslim tourists, but Kobayashi points out that they come from every corner of the globe, illustrating the breadth of the market. She says that compared to when she launched her company, the number of shops in Japan catering to Muslims has increased, demonstrating a growing awareness and acceptance of Islamic culture in Japan. “It’s not unusual to see a woman wearing a hijab in public anymore,” she explains. “And because of Xiaxia, many of my friends have set aside their misgivings and are much more impressed by what I’m doing.” Her hope is that her efforts will foster mutual understanding by bring Japanese and Muslims together in the places where they live and work.

Kobayashi wants to create opportunities for Japanese and Muslims to learn about each other’s cultures. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Beauty as a Borderless Thing

Kobayashi has big plans for Xiaxia, which she touts as Japan’s first domestic hijab brand. She is looking to expand her offerings to items like the abaya, a loose-fitting overgarment popular in many Islamic societies. She says that she has received requests to design the garments with matching hijabs and is keen to meet her clientele’s demands. “By combining the beauty of two items, the kimono hijab serves as a starting point for fostering cultural understanding.”

Xiaxia’s homepage poignantly proclaims, “True beauty knows no borders.” Taking these words to heart, Kobayashi in her kimono hijabs has found her calling in serving as a bridge to link Japan and Muslims through fashion and culture.

Xiaxia Hijab Japan

- Website: https://xiaxiahijab.com

- Online shop: https://xiaori.thebase.in/

(Originally published in Japanese. Text and interview by Nippon.com staff. Banner photo: Kobayashi Kaori shows off a selection of her kimono hijabs. © Hanai Tomo.)