Japan’s Fascination with Train Station Melodies

Culture Travel Music- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Station Songs

Singer Sakamoto Kyū (1941–85) is best known for his 1961 hit “Ue o muite arukō” (Look Up as You Walk), released internationally as “Sukiyaki,” which topped the charts in the United States, Australia, and other countries.

In Kawasaki, where Sakamoto was born, the JR and Keikyū railway companies both play the melody on their station platforms to notify passengers when a train is about to depart. This came about through efforts by the local chamber of commerce and other parties to use the famous singer’s connection to Kawasaki to promote the city. The “departure melody” is a 10-second arrangement based on the original song’s familiar introduction and chorus.

Kawasaki is a major city, between Tokyo and Yokohama, with a population of over 1.5 million. Because of the high frequency of train departures, the melody has to be short, but in rural areas of Japan with less frequent trains, melodies can be as long as 20 or 30 seconds, some stations also play an extended tune as a train approaches.

Astro Boy and the Privatization of JNR

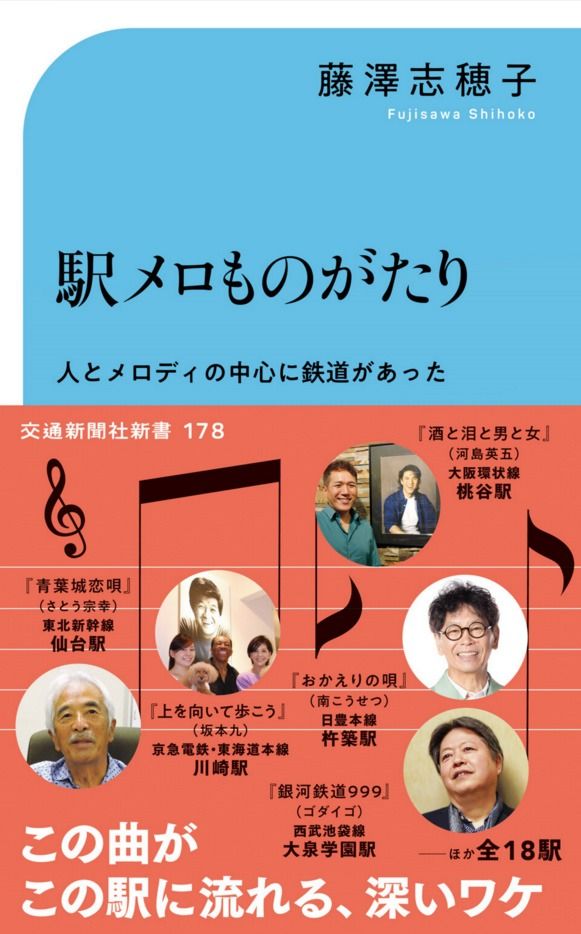

I visited train stations around Japan that had adopted melodies as a strategy for local revitalization. I wrote about 18 of them in my book Eki mero monogatari (Tales of Train Station Melodies), published in April 2024.

Station melodies are a distinctive aspect of Japanese railway culture. I consider myself a railway fanatic, and make every effort to travel by train while on holiday in Japan and overseas, or when traveling for business. I have ridden Amtrak in the United States, Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway, trains in Western, Central, and Eastern Europe, Canada, and China, South Korea, and other Asian countries, but in many cases, there is no sound to signal departures, let alone a melody. Trains simply depart when the allotted time comes (and are often delayed). Being on board in time is left entirely in the hands of passengers.

Meanwhile, Japan is renowned for its timely train service. In 1872, Japan’s first railway was constructed between Shinbashi in Tokyo and Yokohama. At the time, a taiko drum and bell were used to notify crew members of the departure.

It was not until 1912 that a bell was sounded to alert passengers, at Tokyo’s Ueno Station. Melodies were first introduced in 1987, after the privatization of the former Japan National Railways, predecessor to today’s Japan Railways companies. In 1989, bell sounds were replaced with melodies at Shinjuku and Shibuya stations on the JR Yamanote Line. It was the heady days of Japan’s bubble economy, and at overcrowded stations, the shrill bells tended to spur passengers to rush for the trains. It was suggested that more pleasant melodies would calm passengers and help to reduce such risky behavior.

The first melody that was deliberately chosen to reflect the locality was at JR Takadanobaba Station, in 2003. The tune chosen was the title song of the anime based on Tezuka Osamu’s manga Tetsuwan Atomu, (Astro Boy). In the original story, Astro Boy was created at the fictitious Ministry of Science, located in Takadanobaba, in April 2003. Furthermore, Tezuka Productions, the animation studio founded by Tezuka, is still based there. Consequently, the local shopping association proposed the melody’s use at the station, which is still played to this day.

Japan’s Oldest Station Melody

In fact, though, there is an even earlier example of use of a melody at a station.

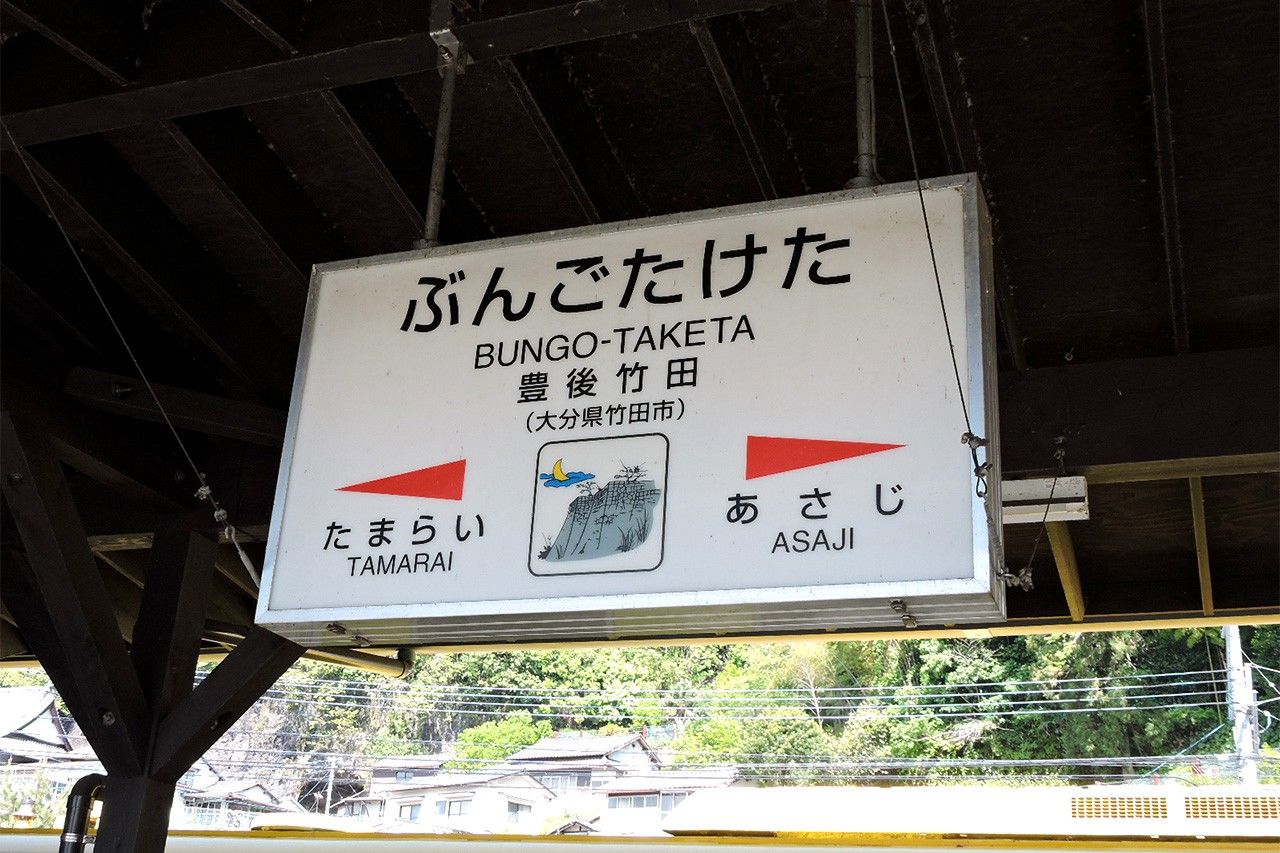

The first I have been able to confirm was the adoption in 1951 of “Kōjō no tsuki” (The Moon over the Ruined Castle), composed in 1901, at Bungotaketa Station in Ōita Prefecture.

The composer, Taki Rentarō (1879–1903), spent some of his youth in the city of Taketa, and wrote the piece with the ruins of the city’s Oka Castle in mind. Apparently a local resident brought a vinyl record of the piece to the station and played it over a megaphone whenever trains departed.

At the time, vinyl records were poor quality, and the local newspaper reported in 1963 that 80 records were worn out in the first 12 years. Since 1988, the station has played a recording by a local girls’ choir.

The Bungotaketa Station platform. (© Fujisawa Shihoko)

Many people may wonder what led to the introduction of station melodies in the turbulent post-war period. In Taketa, it can be traced to the city’s history as a home to secret Christian believers in the Edo period (1603–1868). Christianity imparted an interest in overseas culture among locals. Even before World War II, there are records of the local town council discussing promotion of tourism to help revitalize the town.

Taketa is quite rustic compared with Ōita’s more famous spa resorts, Beppu and Yufuin, but locals had a strong urge to share their pride in Taki and to promote his achievements. After the war, they launched a memorial music festival, which became the Taki Rentarō National High School Vocal Competition, held for the seventy-eighth time in 2024. Thus, the introduction of station melodies can be traced back to efforts by citizens to rejuvenate their communities.

Can Station Melodies Hit the Right Note with Overseas Visitors?

The end of the COVID-19 pandemic and the weak Japanese yen have brought a rapid influx of visitors to Japan. I had hoped, in vain, that they might be interested in the station melodies.

At the JR and Keikyū Kawasaki Stations, I do not get any sense that overseas visitors even notice that Sakamoto’s “Sukiyaki” is playing. Outside the stations there is a plaque introducing Sakamoto’s spectacular achievements, but alas, it is only written in Japanese. If an English version could be added, it could spur the interest of overseas visitors.

The Kawasaki memorial plaque for Sakamoto Kyū. (© Fujisawa Shihoko)

“Sukiyaki” has been covered by many musicians, both in and outside of Japan. Even Ben E. King (1938–2015), best known for his hit “Stand By Me,” recorded a version. King released a charity album in 2011 following the Great East Japan Earthquake, on which he sings the song in its original Japanese. When he visited Japan to perform, he met with Sakamoto’s widow, Kashiwagi Yukiko. If Kawasaki erected a monument including such information, I am sure it would spark more interest among visitors from overseas.

There is an interesting case near Mount Fuji, a leading sightseeing destination for foreign tourists. Fujikyūkō, a railway running 26.6 kilometers from Ōtsuki, Yamanashi Prefecture, is nowadays packed with overseas visitors hoping to photograph Mount Fuji as the train passes close by. Shimoyoshida Station, in Fujiyoshida, is especially popular, and sees many tourists alighting to take pictures.

The view of Mount Fuji from the Shimoyoshida Station platform. (© Fujisawa Shihoko)

The station plays hit songs by local group Fujifabric on its platforms to alert passengers of train arrivals and departures. The songs, “Wakamono no subete” (Everything About Youth) and “Akaneiro no yūhi” (Crimson Sunset), written by former group member Shimura Masahiko (1980–2009), have been played in their original format, with vocals, since December 2021.

Shimura wrote these and many more songs with his hometown in mind. Use of the songs was first proposed by a station worker and former classmate of Shimura, hoping to increase awareness of the musician among station users. Finally, after two years of effort, the songs were introduced at the station. A board erected at the station has information about the achievements of Shimura and Fujifabric that includes the song lyrics. It has been translated into English, Chinese, and Thai for the benefit of overseas visitors.

The information board at the Shimoyoshida Station platform. (© Fujisawa Shihoko)

But when I visited in January 2024, all of the tourists appeared too busy photographing Mount Fuji to notice the panel. Perhaps more information in Japanese and English about Shimura could be posted elsewhere in Fujiyoshida City and at Mount Fuji to better alert visitors.

How can Japan share its culture of station melodies with more people around the world? It is my hope that JR Karuizawa Station, in Nagano Prefecture, could use “Imagine” by John Lennon as its melody. John and Yoko Ono had a holiday house in the town, historically a popular summer retreat, and spent long sojourns here in the 1970s with their son Sean. Even today, fans visit the town to see sites associated with Lennon. You may say I’m a dreamer, but if the town’s major gateway, its station, could play his famous ballad, imagine all the people who would hear about it.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)