Hinako and the Wolf: A Tale of Surprising Discovery and a Young Researcher’s Passion

Environment Science Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Visiting a special mammalian exhibit at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo in spring, I had an unexpected encounter with a Japanese wolf. Canis lupus hodophilax, the celebrated—but sadly extinct—Nihon ōkami. I leaned forward to read the explanation plate, which proclaimed the small canid to be a newly identified specimen. Only five mounted specimens of Japanese wolves have been identified up to now—one each in the Netherlands and Britain and three in Japan—and the discovery of a sixth by a Komori Hinako, a sprightly Japanese schoolgirl, has produced a buzz in certain taxonomy circles.

The newly identified Japanese wolf on display at the National Museum of Nature and Science. (© Hayashi Michiko)

Chance Encounter

The tale begins in November 2020 when Komori, who is now in junior high, was a fourth grader in elementary school. She had coaxed her father into joining her on a tour of the National Museum’s Tsukuba Research Departments in Ibaraki Prefecture, which opens its doors to the public once a year. The sprawling research facility stores the museum’s vast collection of natural specimens, and while Komori was meandering through the taxidermy area, a mounted dog-like specimen tucked away on a shelf drew her interest.

She was struck by the beast’s uncanny resemblance to a Japanese wolf, a species that fascinated her. Humming with excitement, she e-mailed the museum for information on the intriguing specimen, but other than a label identifying it as yamainu (literally “mountain dog”) and the catalog number M831, nothing was known. It was enough to fuel her curiosity. She had a hunch that the stuffed creature was in fact a Japanese wolf as the term yamainu was widely used in the past to describe both wild-roaming domestic dogs as well as their more cunning and fierce cousins.

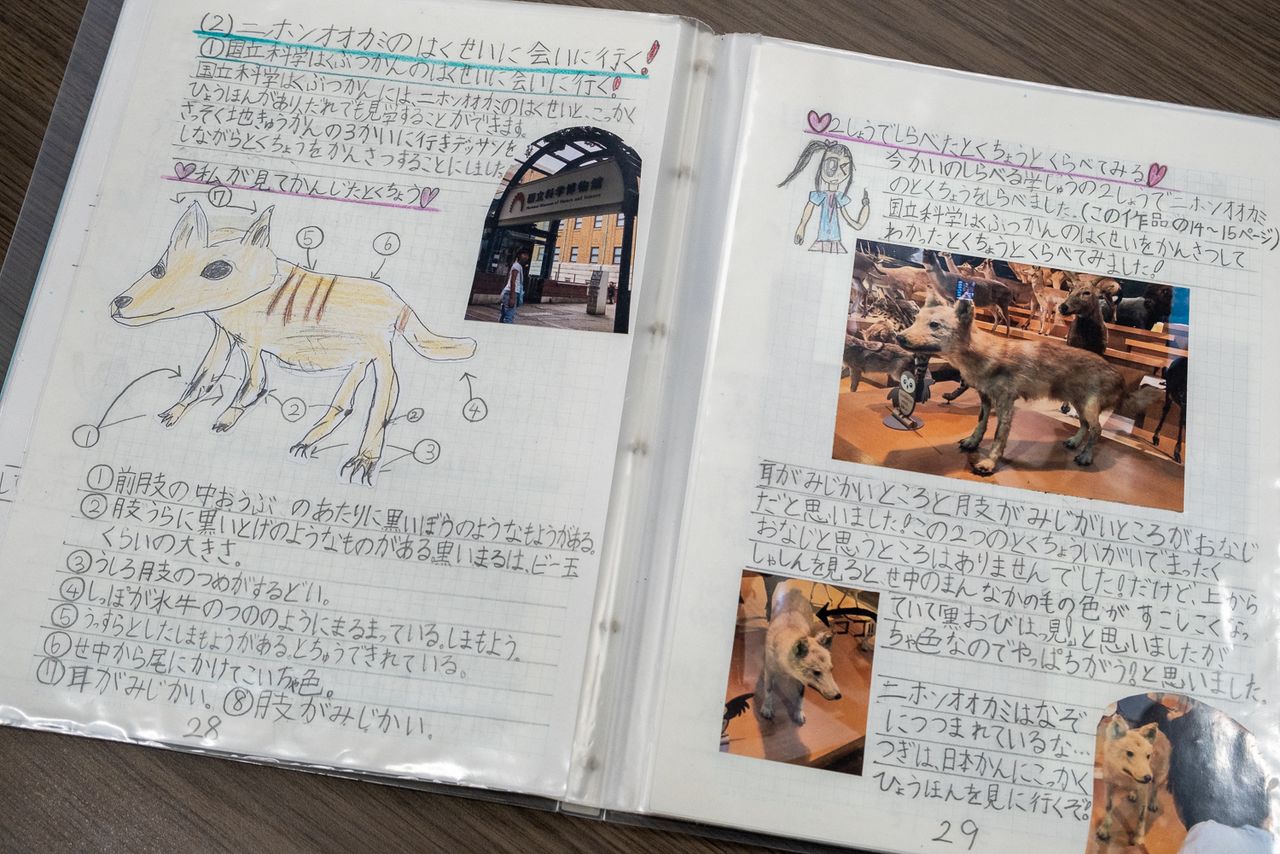

She began poring over old books and records, excitedly noting down each piece of evidence she came across. She even received special permission to examine the stuffed creature, comparing its taxonomy against other known specimens. As she progressed in her research, she garnered support from two experts: Kawada Shin’ichirō from the museum’s zoology department and Kobayashi Sayaka, a researcher at the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology and an authority on early Japanese specimen registries.

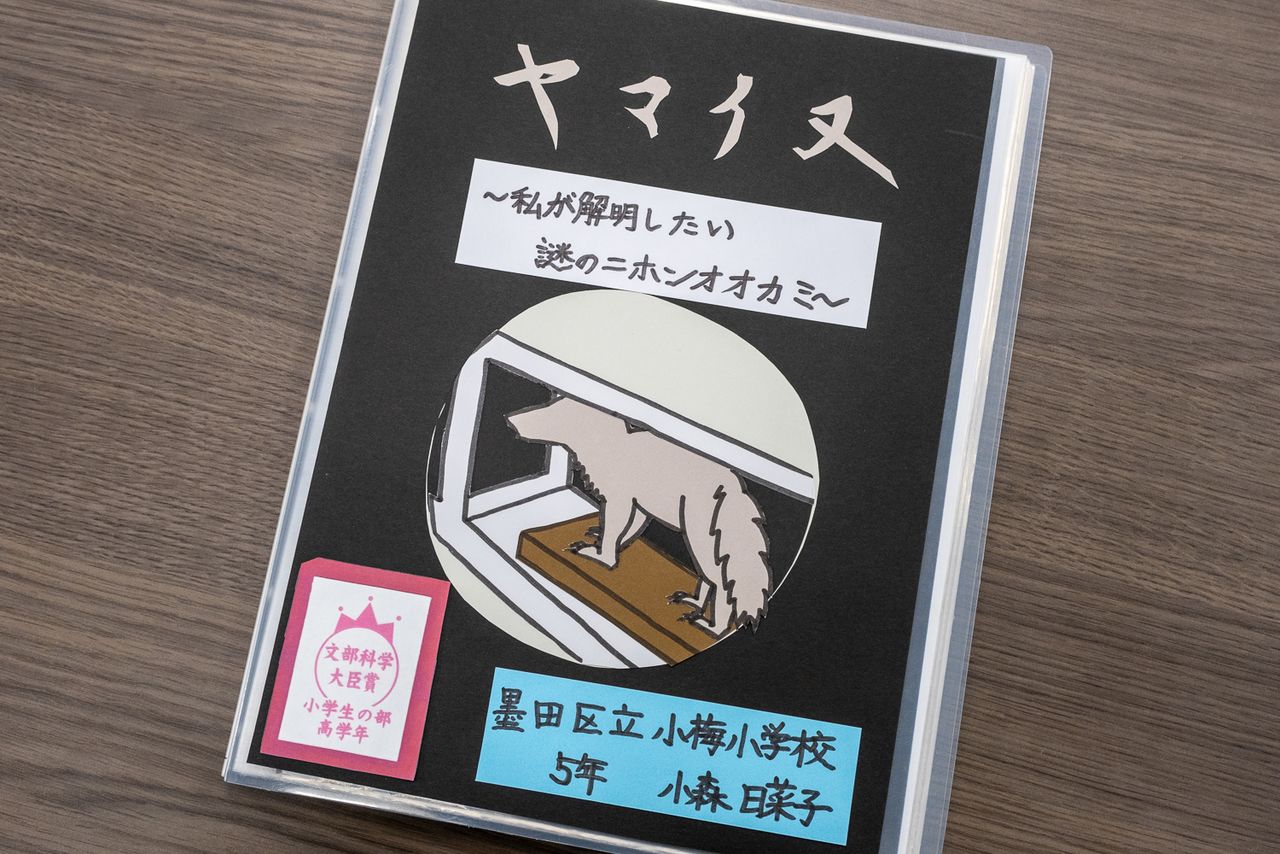

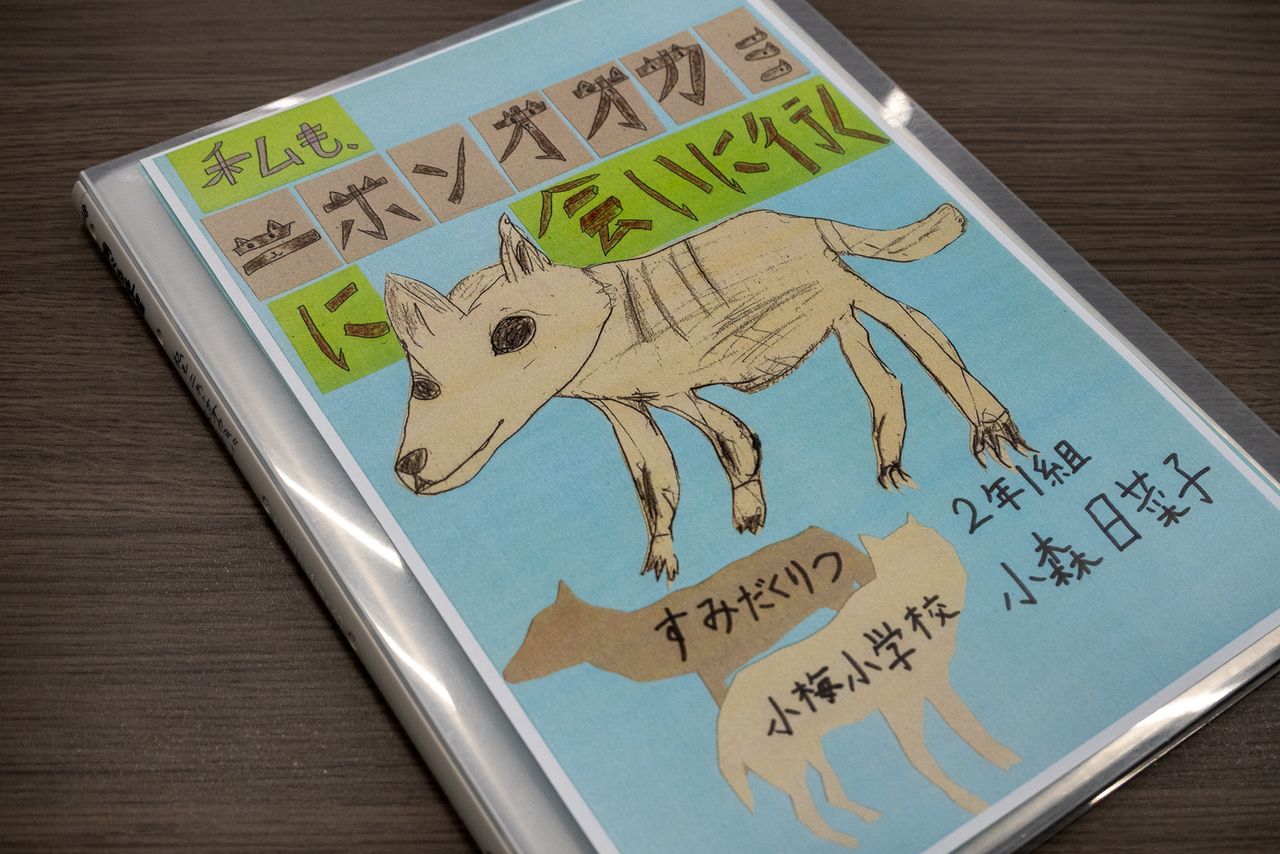

With advice and encouragement from the two, Komori spent her fifth-grade summer compiling her findings in a hand-written report arguing that the unidentified specimen was a Japanese wolf. She submitted her work to a research contest for elementary school students, earning her a prestigious prize from the education ministry.

The cover of Komori’s 76-page report. (Courtesy the Foundation for Library Advancement)

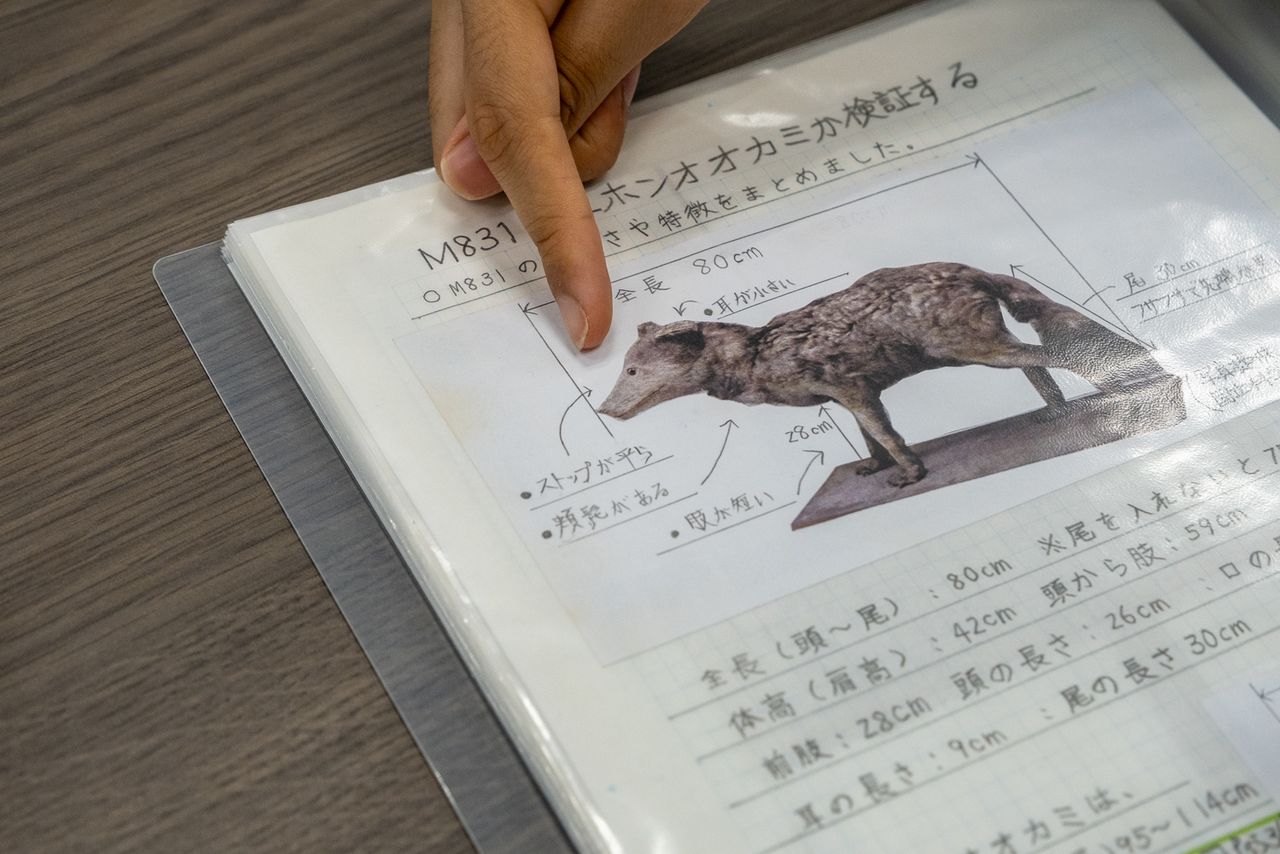

Komori compared the mysterious yamainu with a Japanese wolf specimen preserved at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, the Netherlands. (Courtesy the Foundation for Library Advancement)

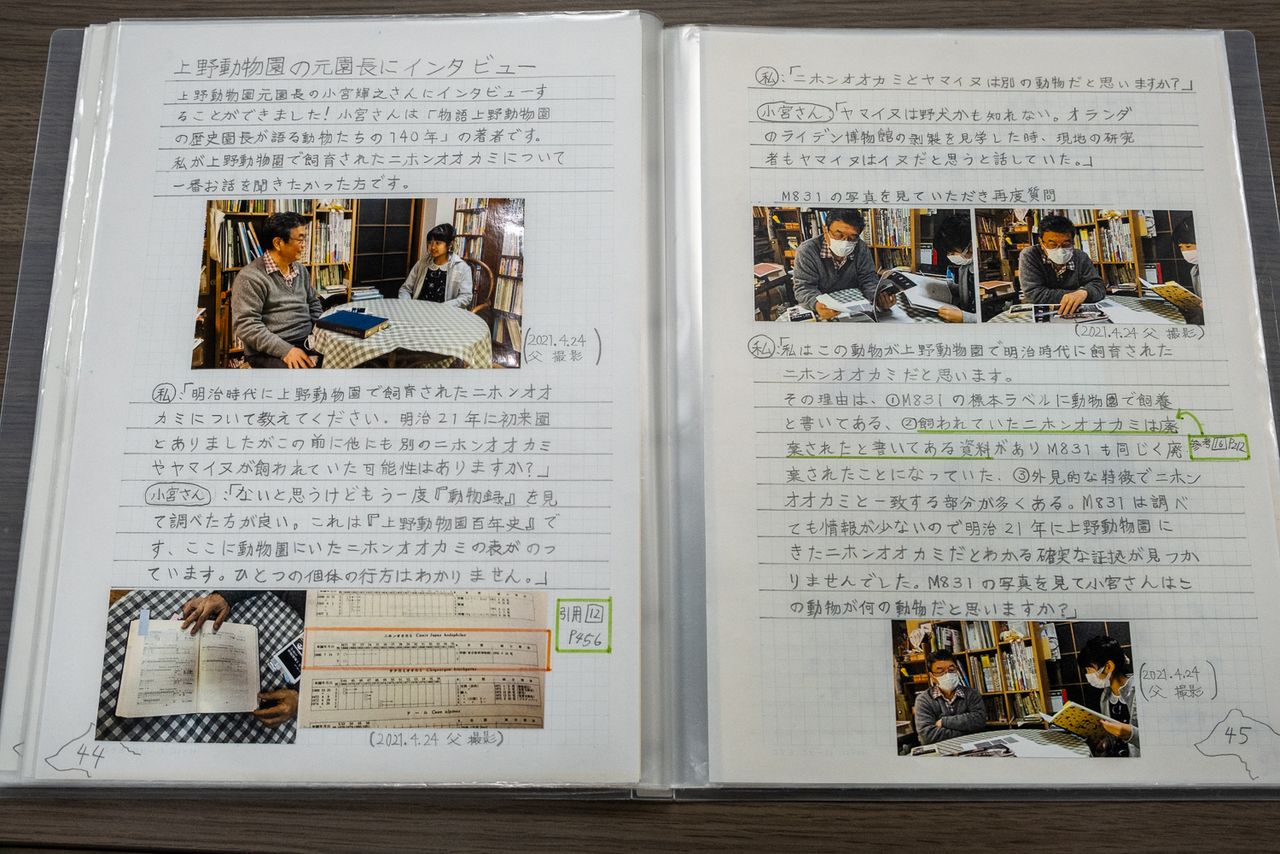

As part of her research, Komori interviewed a former director of Ueno Zoo, who wrote a history of the facility. (Courtesy the Foundation for Library Advancement)

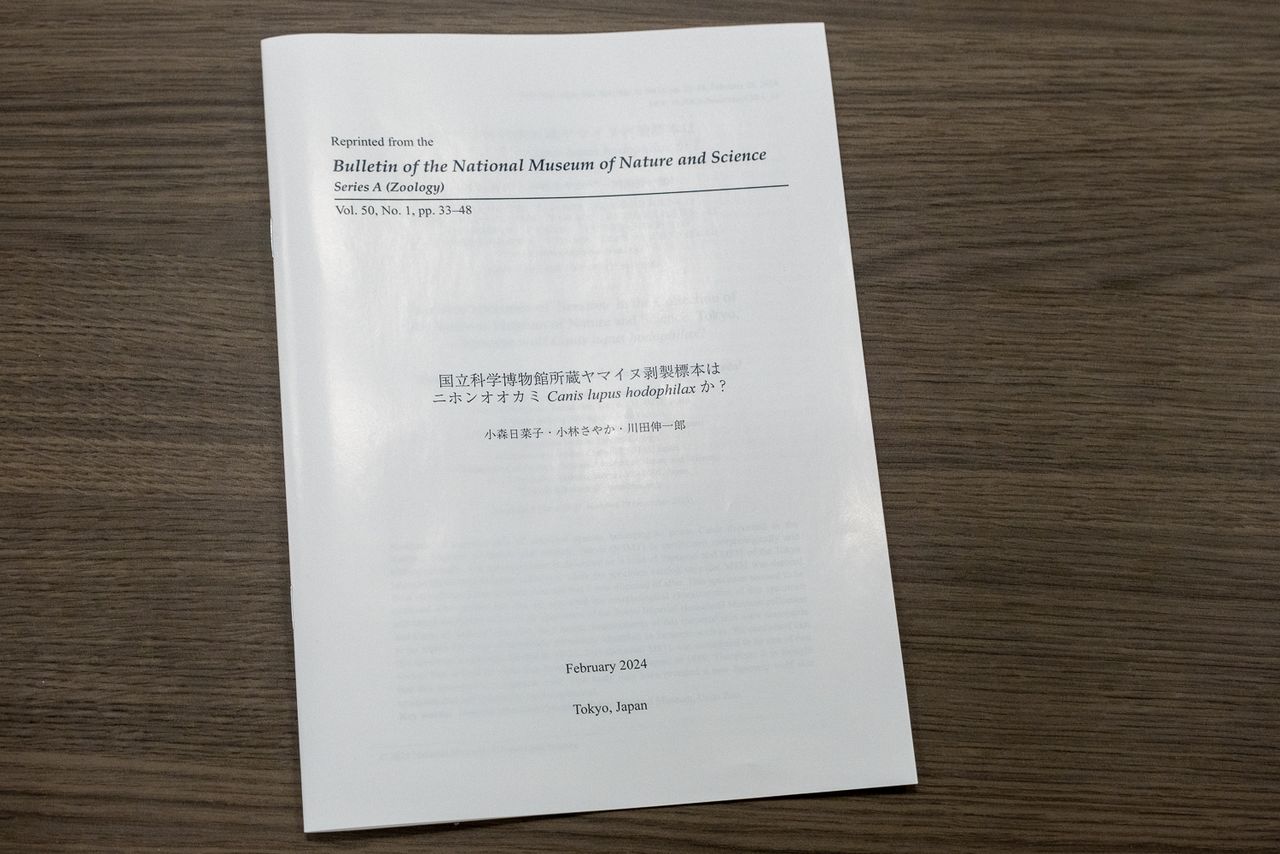

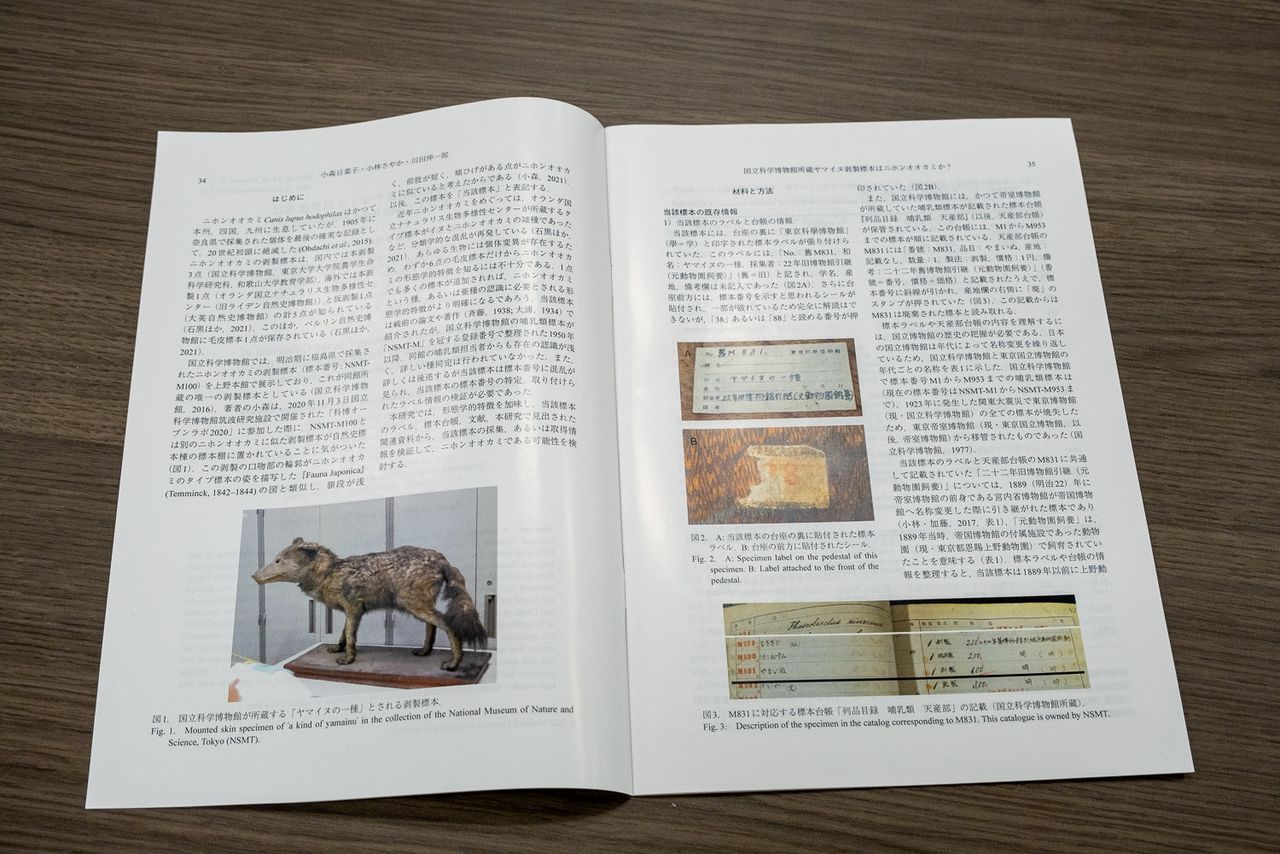

Impressed with Komori’s report, Kawada and Kobayashi suggested to the young researcher that the three team up to publish a scientific article based on her findings. Over the course of two years, Komori and her co-authors scoured reams of documents and other materials on Japanese wolves that might shed light on the specimen’s pedigree. After settling on a format and subjecting the paper to review, they published the article in February 2024 in the bulletin of the National Museum of Nature and Science, with Komori, now in the first year of junior high school, as the lead author.

Kawada lauds Komori’s work, saying that “the Japanese wolf is extinct, sadly, so we need more specimens to examine if we hope to gain a clearer understanding of its place in the canid family.” Relying mainly on previously published studies, the three compared these data against the morphology and traits of M831 and were able to declare with confidence that the specimen “falls within the range consistent with Japanese wolves.”

The article is the culmination of Komori’s dedicated research starting when she was in elementary school. (© Hayashi Michiko)

Missing Identity

Reaching this conclusion, though, was no easy task. The first order of business for Komori in her investigation was to get to the bottom of the specimen’s origins. The label M831 attached to the pedestal matched an entry in a specimen catalog kept at the museum, but there was a second damaged label with only an “8” and part of another number visible. More worryingly, however, was the entry, which included a character stamped in red indicating that M831 had been discarded. Confusing matters even more was the fact that the National Museum of Nature and Science’s predecessor, the Tokyo Museum, had been destroyed—documents, specimens, and all—in the conflagration that followed the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake.

Subsequently, part of the natural history collection along with records from the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum (now the Tokyo National Museum) had been transferred to the Tokyo Museum. More had been transferred during the tumultuous war years, tying the document trail into knots. To unravel the maze-like jumble of information, Kobayashi suggested that Komori draw up a list of all the canid specimens that had been held by the Imperial Household Museum and Ueno Zoo.

Poring over reams of microfilm, Komori found that in 1888 Ueno Zoo had taken possession of two juvenile Japanese wolves from Iwate Prefecture. Digging further, she was able to piece together clear evidence showing M831 to be one of the two animals. She had been right; the yamainu was a Japanese wolf.

Kobayashi Sayaka says that she interacted with Komori like any other researcher. (© Hayashi Michiko)

More Work to Do

Even with the published article, many unanswered questions remain. Kobayashi notes that while the Imperial Household Museum records identify the specimen as a Japanese wolf, it is possible that it is a wolf-dog hybrid produced from mating with a domestic dog. She says that genetic analysis is the only way to know for certain whether it is a purebred wolf or not. However, Kawada says that the museum has no plans to do DNA testing, which requires taking samples that damage specimens, an especial concern due to the age and poor condition of Komori’s wolf.

Determining if a specimen is a Japanese wolf typically involves analyzing the skull, but it is unclear if M831 contains any bones or is simply a mounted skin. Kawada hopes to take an X-ray of the animal someday, but at the moment he is pleased that the specimen managed to survive to the present and is garnering attention after so long in the shadows. “Future advances in DNA analysis may allow researchers to run tests from tiny samples,” he speculates. “This would certainly expand the research potential of specimens. I have to keep these things in mind and carefully preserve specimens for the next generation of scientists.

Kawata Shin’ichirō looks after the animal collection stored at the Tsukuba Research Departments, which includes some 86,000 mammal specimens alone. (© Hayashi Michiko)

Komori Hinako talks about the work that went into her research project. (© Hayashi Michiko)

Born a Researcher

A self-professed animal lover, Komori says that she has been fascinated by all things zoological since she was a toddler. At the age of three, for instance, she took an avid interest in endangered species after watching an online video on the topic, which led her parents to take her to the Museum of Nature and Science in an attempt to satiate their young daughter’s curiosity. Komori recounts how she was transfixed by the exhibits, spending what seemed like ages to her mother and father examining and comparing each of the animals on display. The museum became a regular outing for the family, and it was there that Komori first came face-to-face with the Japanese wolf.

Although Japanese wolves have been declared extinct, whispers of sightings continue to trickle from mountainous areas, which she says fed her curiosity. As a second grader, she did a research project on the animals, gathering information online and visiting places where wolves had been allegedly spotted or where they were historically known to have roamed. She interviewed locals and collected accounts of sightings, compiling her findings into a 50-page report.

Komori on the cover of her report expresses her desire to find the Japanese wolf. (© Hayashi Michiko)

Komori’s keen observations in her report belie her young age. (© Hayashi Michiko)

Komori shows off a selection of her reports, and research material about Japanese wolves that she has collected. She says when she was younger, she would ask her father for help or consult a dictionary when faced with old and archaic characters. (© Hayashi Michiko)

Nihon Ōkami

The Japanese wolf once roamed across the mountains and forests on each of the major Japanese islands, save for northernmost Hokkaidō. A fearsome creature, it kept the hordes of wild boar, deer, and other crop-damaging animals in check, earning it veneration in some areas as a guardian deity and messenger of the gods.

In modern times, though, the wolf began to succumb to external pressures, with diseases like rabies and canine distemper ravaging populations. In livestock breeding regions in northern Honshū and elsewhere, it was reviled as a pest, and in the late nineteenth century it was made the target of bounty hunting. The last known wild wolf was killed by hunters in the mountains of Nara Prefecture in 1905.

The appellation Nihon ōkami, or Japanese wolf, to describe the species is a relatively new invention, dating only from the postwar period. It is frequently listed in reference material as yamainu, and historically it went by such names as ōkami, ōinu, oino, and kasegi, suggesting the wide disbursement of the species.

Wolf statues stand guard at the Mitsumine Shrine in Chichibu, Saitama Prefecture. (© Hayashi Michiko)

Modern scientific study progressed in tandem with Japan’s rapid industrialization following the 1868 Meiji Restoration. Authorities rushed to hold national industrial exhibitions and establish museums dedicated to science and industry, which fueled a rush to collect and document every variety of flora, fauna, and mineral. Amid this, there was a modest effort to preserve specimens of the Japanese wolf, and much of what is known about the animal comes from a small collection of bones and mounted skins held by educational institutes and museums.

A mounted Japanese wolf specimen at the University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Agriculture. The animal was procured from Iwate Prefecture for the Second National Industrial Exhibition in 1881. (Courtesy University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Agriculture)

Taxonomic Confusion

The Japanese wolf became known to the broader world in the first half of the nineteenth century through the efforts of Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866). The Bavarian-born doctor, who spent six years at the Dutch trading post in Nagasaki, included three specimens among the huge collection of Japanese animals, plants, artworks, and maps that he took back with him to the Netherlands in 1830.

Siebold sent the specimens—a mounted skin, a skeleton with a skull, and two skulls—to Dutch zoologist Coenraad Jacob Temminck (1778–1858), head of the National Museum of Natural History in Leiden, describing them as being examples of ōkami and yamainu. Temminck determined that they differed from the grey wolf native to Eurasia and North America and represented a new subspecies, which he christened Canis hodophilax.

A drawing of the mounted specimen was included in the section on Japanese dogs and wolves in the nineteenth-century collection Fauna Japonica, and together with the skeleton with skull, it has served as type-specimens for subsequent research of Japanese wolves, despite being labeled as yamainu.

An illustration of Canis hodophilax from Fauna Japonica. (Courtesy of the Division of Biological Sciences, Kyoto University)

Recent analysis of the nuclear DNA of the Leiden specimens has shed light on their taxonomy. Among the three, the skeleton with skull was found not to be a wolf, but a domestic dog. The stuffed animal, meanwhile, is most likely a wolf-dog hybrid.

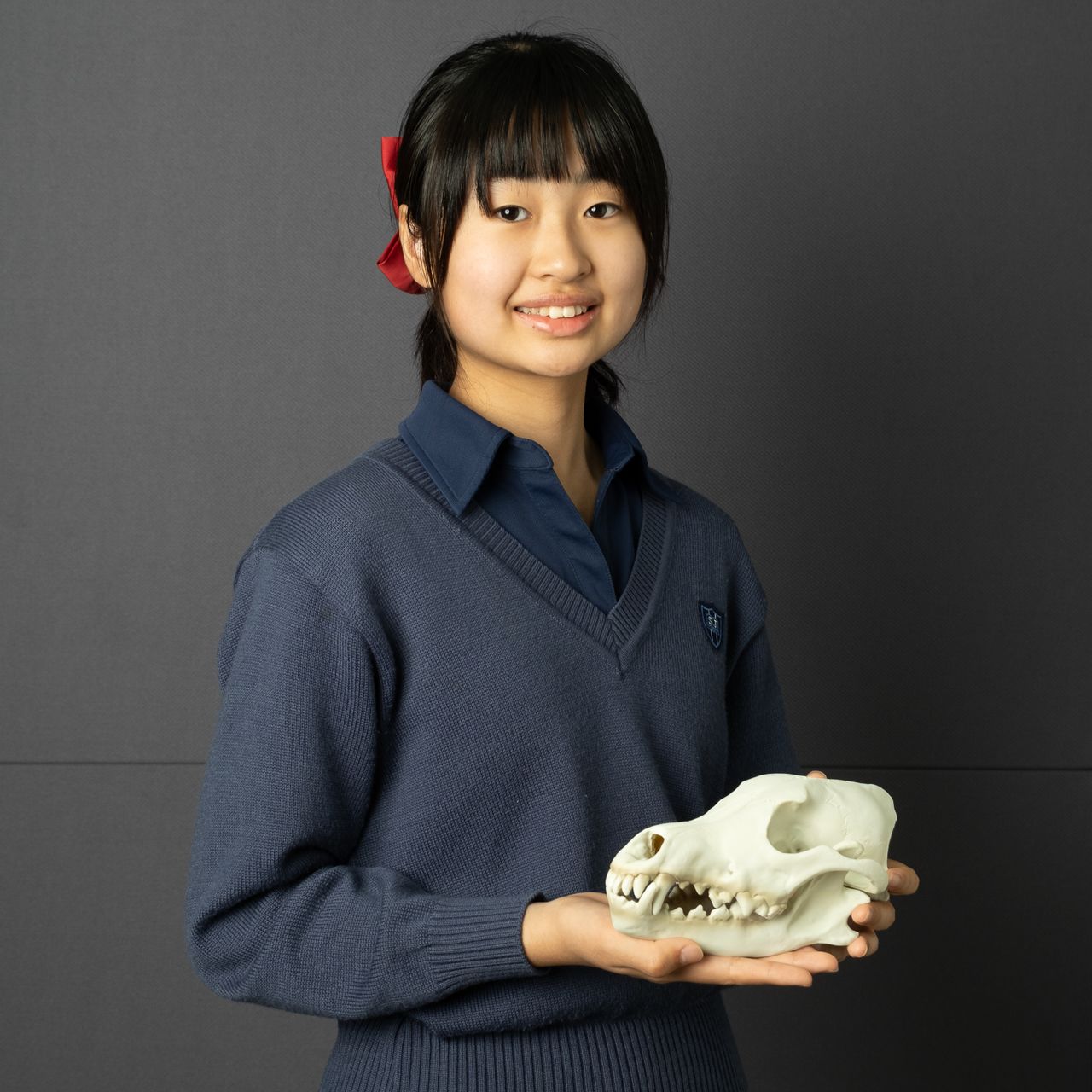

Komori holds a model of a Japanese wolf skull she received as a gift from her parents after publishing her report. (© Hayashi Michiko)

Komori hopes that the identification of M831 as a Japanese wolf will clear some of the mystery around the species and lead to new specimens and documents being discovered that will help flesh out the amount of available research material. “The more I study Japanese wolves,” she says, “the more interesting they are.” She intends to continue her research into the taxonomy of the creatures while delving deeper into the written record. “There are significant discrepancies among the different known specimens, but having so many unanswered questions is what makes the species so fascinating.”

Komori’s curiosity is certain to lead her down new and fascinating paths of research in the years ahead. Wherever it might take her, she can be expected to bring the same dedication and enthusiasm she has to her study of the Japanese wolf.

Komori and her wolf. (© Hayashi Michiko)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Komori Hinako and the Japanese wolf specimen she discovered at the National Museum of Nature and Science’s Tsukuba Research Departments. © Hayashi Michiko.)