From Refugee to Highly Skilled Engineer: The Syrian Man Working from Japan to Help His Homeland

People Society Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Refugees in Japan

Syria has been ravaged by civil war for 13 years and counting, fueling what the United Nations Refugee Agency has labeled as the “world’s largest displacement crisis.” As of May 2024, 13.8 million people have been forced from their homes. Some 6.4 million of those displaced have fled abroad, with the majority settling in neighboring countries like Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan. Western countries—notably Germany and Sweden—have also accepted thousands or tens of thousands of refugees.

Japan, on the other hand, remains averse to asylum seekers. While it granted refugee status to a record number of people for the second consecutive year in 2023, the total came to a mere 303 individuals—a recognition rate of around 2%—far below other G7 countries. In 2023, the government gave 17 Syrians leave to remain in the country out of what it called “humanitarian considerations,” but granted only one Syrian refugee status.

Refugee policy is a fraught issue, and it is unlikely that the situation in Japan will change significantly any time soon. The government, therefore, needs to provide other options for displaced people to remain in the country beside recognition as refugees. The Japanese Initiative for the Future of Syrian Refugees, which aims to be a bridge between Japan and Syria by helping refugees and their families built better futures, is one undertaking that is achieving results in this direction.

The JISR program, which is administered by the Japan International Cooperation Agency, provides assistance for young Syrians in places like Lebanon and Jordan who have been recognized as refugees by the UNHCR to come to Japan to study. After finishing a year-long Japanese language course, participants are eligible to receive assistance for two years to pursue a master’s degree at a Japanese university, with most choosing fields like engineering, telecommunications, management, or health sciences. The program covers travel costs, tuition, and living expenses, and those who bring their families to Japan are provided an allowance for dependents. Participants are able to intern with Japanese companies while they study. The program has brought 79 people to Japan since its launch in 2017, with a significant number of more than 50 individual who have completed the JISR program going on to work for Japanese companies.

Connecting Syrian IT Talent with Japan

Iskandar Salama came to Japan in 2018 as part of the second batch of students on the program. Today, the 32-year-old works as chief technology officer at BonZuttner, a systems development company.

Iskandar Salama. (© Nippon.com)

Iskandar studied computer science and programing at Damascus University, Syria’s leading institution of higher education, and went on to work as a web engineer and adjunct faculty member at the school. He says that he had always been fascinated by “high-tech Japan” and dreamed of studying artificial intelligence at the graduate level at a Japanese university. When he heard about the JISR program after fleeing Syria for Lebanon, he applied without hesitation.

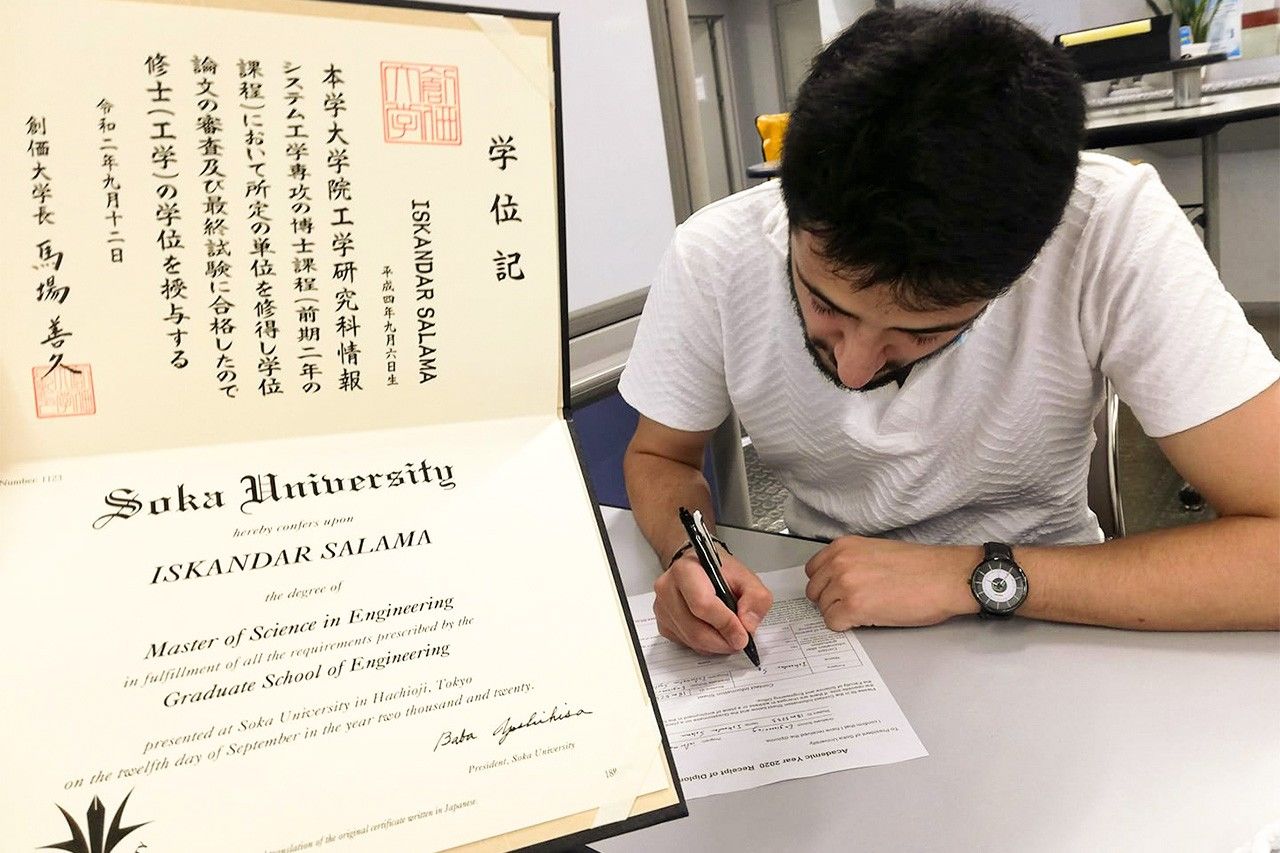

He was accepted to the Graduate School of Science and Engineering at Sōka University and took a job with Tokyo-based BonZuttner in 2020 after completing his master’s degree in engineering. He has continued to study generative AI and is working toward a doctoral degree. Salama is in Japan on a highly skilled professional visa, which will help him if he eventually decides to apply for permanent residency.

Iskandar proudly displays his engineering diploma from Sōka University. (© Iskandar Salama)

Iskandar’s main focus at BonZuttner is a project that commissions engineers in Syria and surrounding countries to develop software for mobile apps for Japanese companies. The project allows him to tap into his broad network of contacts in Syria and Lebanon to match talented engineers with work opportunities in Japan.

“I’m able to share the things I have learned and the experience I have gained in Japan with my fellow Syrians,” Iskandar explains. He says that the program is mutually beneficial, providing Syrians who have fled abroad or who are internally displaced opportunities to earn money by putting their technical skills to use while also helping alleviate the shortage of skilled IT workers in Japan.

“I want to establish a reputation for refugee workers in the IT industry in Japan,” Iskandar says, although he recognizes that convincing clients of the skills refugees have is a steep challenge. “Many people in Japan have only a passing understanding of Syria, so the first step is to raise awareness of the country and the situation there.” While much of international focus is on the plight of refugees, around 85 % of the Syrian population lives below the poverty line. Iskandar sees his homeland as offering great potential. “People just need the funding to enable them to develop their talents. What we try to do is put the right people in the right place and help them to become productive.”

While a student in Syria, Iskandar (left) was part of a team that won a collegiate programming contest. (© Iskandar Salama)

Tapping the Pool of Syrian Talent

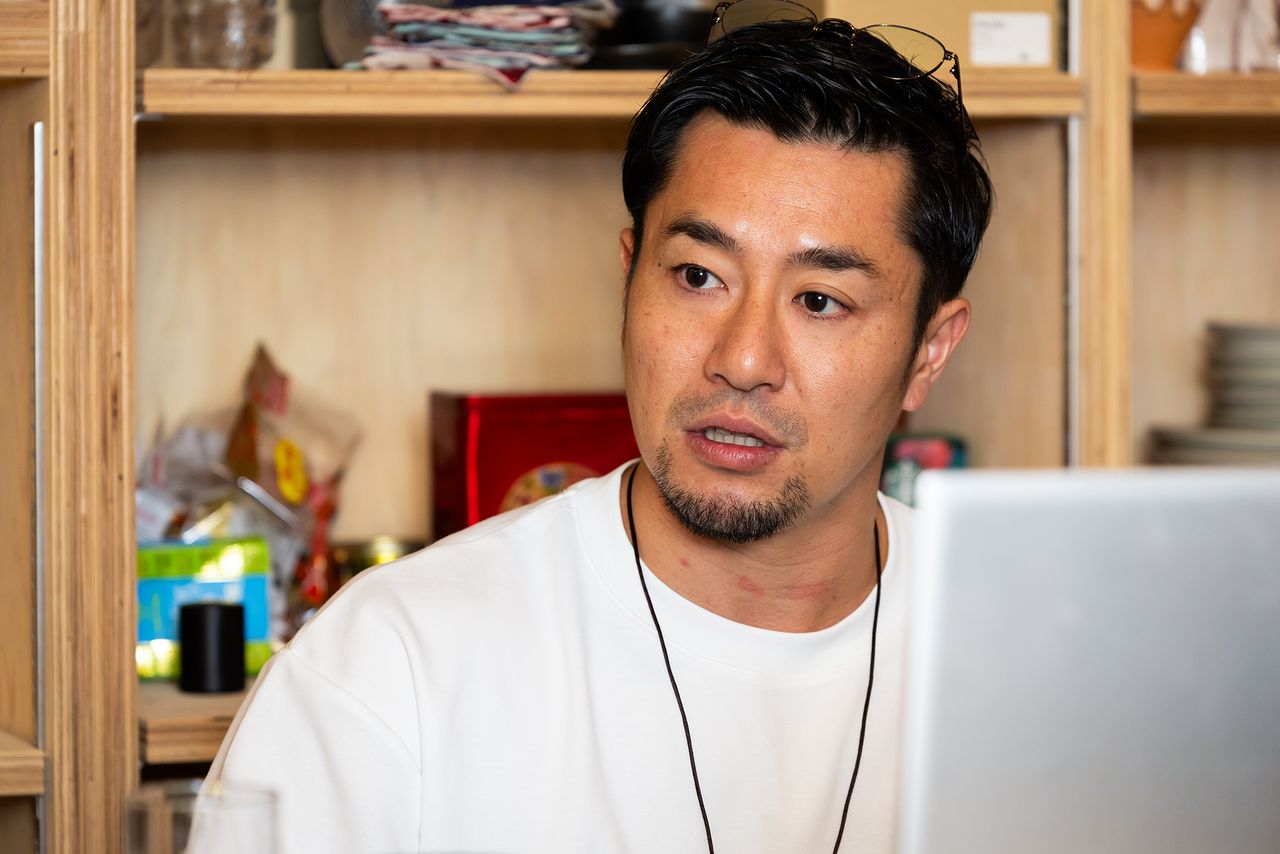

BonZuttner was founded by Sakashita Yūki with the aim of utilizing the experience and skills of refugees in IT fields. Today, it works to find jobs for Syrian engineers who have been forced to flee their homes by the ongoing conflict.

Sakashita first became aware of the terrible situation in Syria in 2015 when a shocking picture appeared in global press of a small Syrian boy whose body had washed up on a beach in Turkey after the boat carrying him and his family capsized. Sakashita eventually became involved with WELgee, an NPO providing support to refugees inside Japan, and it was through his volunteer work that he learned of the difficulty many Syrians face in finding work despite having IT skills that are in high demand.

Sakashita founded his company in 2019, convinced that he would succeed if he could find a way to tap these skills to fill the need for skilled IT workers in Japan. He was joined in his new endeavor by Maher Al Ayoubi, a Syrian IT engineer Sakashita met through his volunteer activities. Iskandar joined the firm the following year.

From left: Maher Al Ayoubi, Iskandar, and Sakashita Yūki. (© BonZuttner)

Sakashita insists that a fundamental solution to the refugee problem cannot be achieved by looking at displaced people from a stance of pity. “We need to view refugees as untapped human resources,” he declares. “They offer skills and experiences that can help revitalize Japanese society, which suffers from a dire lack of manpower brought on by population declines. I started the company with the idea of enabling Syrians to utilize their talents for the benefit of the Japanese business world.”

In Sakashita’s view, companies need to be actively involved in helping refugees capitalize on their IT skills and in developing their careers. He is among a growing group of business leaders and entrepreneurs who are taking the initiative to create employment opportunities for refugees. “It’ll certainly take time for these efforts to burgeon into a broader movement to create a more accepting society and provide a more inclusive kind of professional training,” Sakashita says. “But in Japan, the need of companies for IT workers is increasing all the time.”

Sakashita Yūki. (© Nippon.com)

Empowering Refugee Women

Iskandar calls attention to another significant project BonZuttner is running, one that supports refugee women in finding work. Launched in 2022 in collaboration with Baobab, a Japanese company that provides AI data annotation services, the program aims to provide women who are juggling childcare responsibilities remote-work opportunities in the IT industry. “It allows women, even those new to IT, to work according to their own schedule,” Iskandar explains. “All they need is a computer and internet access.”

Currently, the program mainly supports women in Syria, Ukraine, and various countries in Africa. BonZuttner is responsible for aspects of the program covering Syria and Lebanon, as well as Syrian women living in Japan, including spouses of JISR participants studying at Japanese universities.

Iskandar (third from right) with his coworkers at BonZuttner. (© BonZuttner)

Contributing to Syria from Japan

Iskandar is also involved in “Japan Bridge,” a group that supports people affected by the earthquake that hit Turkey and Syria in February 2023. The group consists mainly of JISR graduates living in Japan who raise money with the goal of providing permanent housing for people who lost their homes in the disaster. At the moment, work is underway on a residence funded by the group that will accommodate four families when it is finished.

During the week, Iskandar concentrates on his work and studies, but tries to leave room in his busy schedule for leisure activities on weekends. He has adjusted to life in Japan, although he admits that he misses home and speaks movingly of his hometown, where he says that everyone was like family. But for now, he remains determined to make the most of his opportunities in Japan by helping his fellow countrymen and others in need.

“If we can grow the company, we’ll be able to offer more opportunities for education and work to people from Syria and other countries in the Middle East,” he says. “In the future, I hope people with the right skills will be able to come and work in Japan, whether they are refugees or not. That’s what I am working toward. Even though I’m living far away, there’s still much I can do for my homeland. And when the time comes, I look forward to contributing to rebuilding Syria from Japan as well.”

Iskandar at the temple Sensōji in Tokyo’s Asakusa district. (© Iskandar Salama)

(Originally published in Japanese based on an interview by Itakura Kimie and Hassan Yūshi of Nippon.com. Banner photo: © Nippon.com.)