“The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō”: The Art of the Highway

Guide to Japan Art History Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Lyricism and Nostalgia

Utagawa Hiroshige was born as Andō Tokutarō in 1797, the son of a fire warden in Edo (now Tokyo). After his parents died successively in 1809, he became the head of the household. From a young age, he was immersed in art, and in 1811 he became an apprentice of the ukiyo-e painter Utagawa Toyohiro. He took the name Hiroshige, using a character from his mentor’s name, and also won the right to call himself Utagawa. He resigned his family position to a relative in 1823, and formally left the fire service in 1832, devoting himself to art until his death in 1858.

![Memorial Portrait of Ichiryūsai Hiroshige [Utagawa Hiroshige] (1797–1858) by Utagawa Toyokuni III. Hiroshige’s death poem is written, expressing a wish that even if he dies and goes to the Western Paradise, he wants to travel around and see the famous places there. (© Henry L. Phillips Collection, Bequest of Henry L. Phillips, 1939; courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art digital archive)](/en/ncommon/contents/japan-topics/2630022/2630022.jpg)

Memorial Portrait of Ichiryūsai Hiroshige [Utagawa Hiroshige] (1797–1858) by Utagawa Toyokuni III. Hiroshige’s death poem is written, expressing a wish that even if he dies and goes to the Western Paradise, he wants to travel around and see the famous places there. (© Henry L. Phillips Collection, Bequest of Henry L. Phillips, 1939; courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art digital archive)

Hiroshige’s master work, The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō, published from 1833, consisted of 55 prints, depicting all the stations of the titular road, as well as the departure point at Nihonbashi, Edo, and the destination of Sanjō Ōhashi bridge in Kyoto. While he created more than 20 later series about the Tōkaidō, this one, known as the Hōeidō edition after its publisher, was both a huge hit at the time, and the best-remembered by posterity. However, Hiroshige was virtually unknown, and Hōeidō a fledgling newcomer. What was the secret of the series’ success?

Inagaki Tomoko is a curator at Okada Museum of Art in Hakone, which is holding a two-part exhibition focusing on the Hōeidō version of The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō until December. She explains that illustrated guides to famous places had been published since the end of the eighteenth century, fostering a yearning for travel. Then, Jippensha Ikku’s comic novel Tōkaidōchū hizakurige (trans. by Thomas Satchell as Shank’s Mare), published at the start of the nineteenth century, became a massive bestseller, building interest in the Tōkaidō highway.

“Hiroshige’s novel approach saw him depict both the travelers on the Tōkaidō and the changes to the scenery through the seasons and in different weather and times of day,” says Inagaki. “This meant they overflowed with a lyricism absent from previous pictures of famous locations, which touched the hearts of the ordinary people. For example, rain is common in Hiroshige’s works, but he consciously distinguished between, for example, heavy evening showers, great downpours, and light drizzle. While reproducing nature with a vivid reality, he added arresting renderings of weather and people. This inspires a somehow nostalgic feeling that strikes to the heart.”

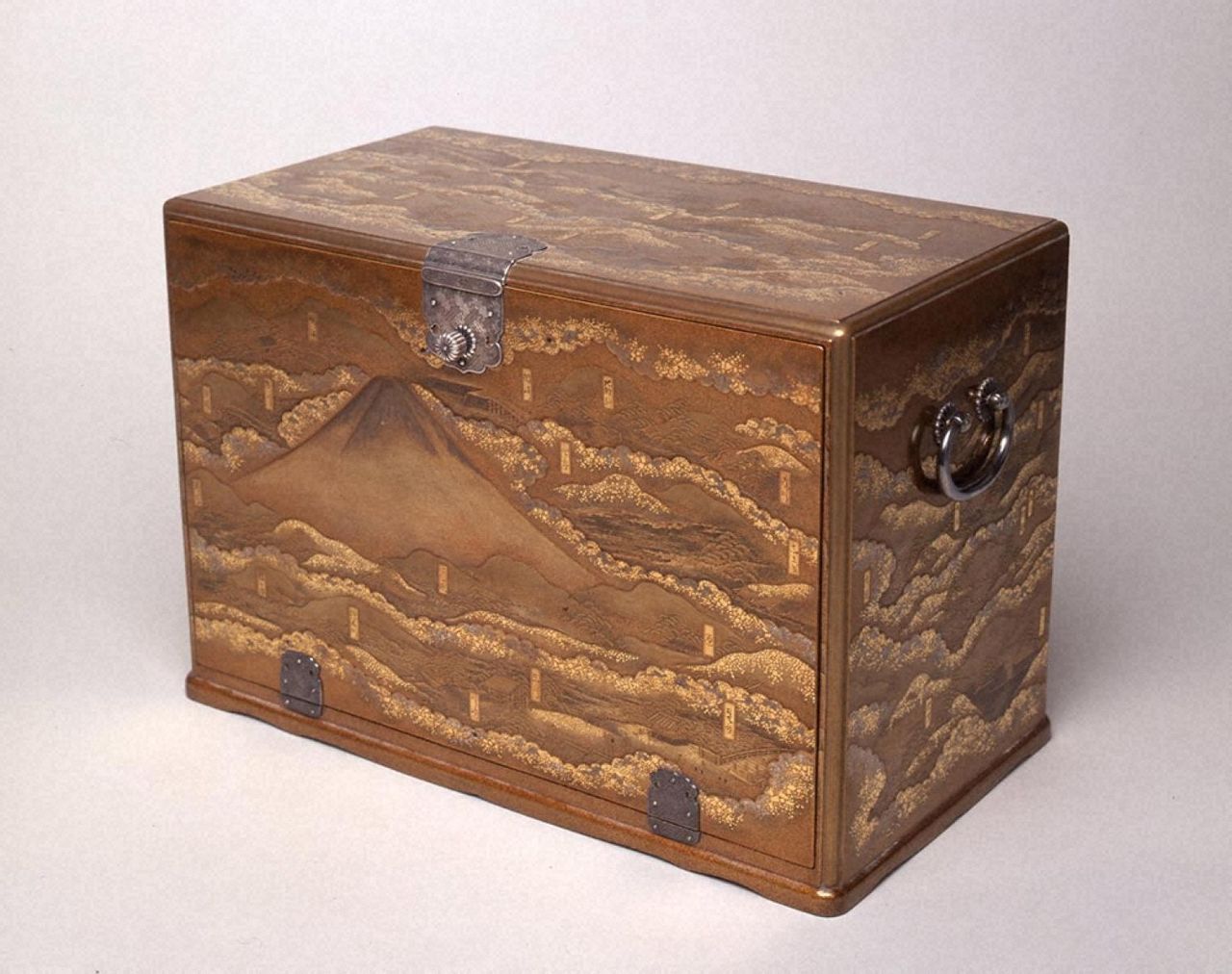

A chest depicting the Tōkaidō winding around four sides from Edo to Kyoto. (Courtesy Okada Museum of Art)

Hakone Patchwork

The Fifty-Three Stations print depicting Hakone is particularly renowned for its elaborate beauty. The mountainous terrain made this the most difficult part of the Tōkaidō to traverse, and Hiroshige depicted this unforgiving landscape in a patchwork of color: green, blue, yellow, and brown. In the distance, Mount Fuji stands modestly all in white, wearing its winter coat of snow.

“A daimyō’s procession, proceeding along a steep, narrow path toward the checkpoint, is represented only by hats,” Inagaki says. “The picture opens up gradually, until Lake Ashi and Mount Fuji come into view, giving a sense of the passing of time.”

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Hakone print from The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. (Courtesy Okada Museum of Art; appears in June–September exhibition)

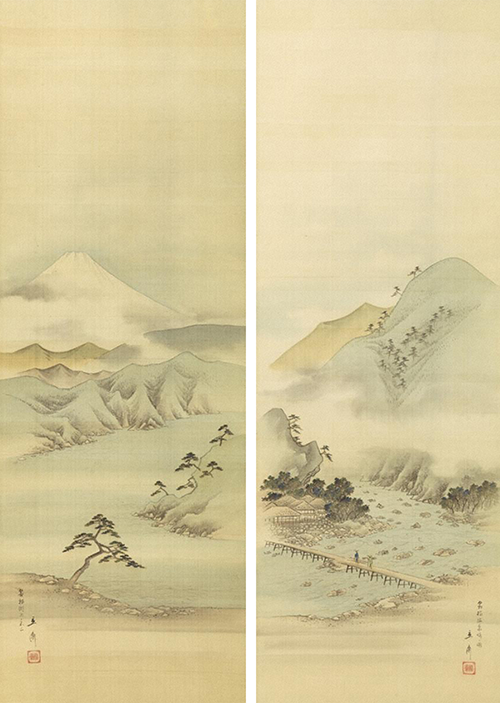

Hiroshige is famous for his woodblock prints, but in his later years, he also painted many pictures for the Oda clan in the Tendō domain (now Yamagata Prefecture). Among these were a pair of hanging scrolls, on show at the Okada Museum of Art exhibition, in the kind of subdued, refined style associated with samurai tastes. To the left is Lake Ashi, with Mount Fuji seen beyond, while to the right is a hot spring, thought to be Tōnosawa.

Pair of hanging scrolls by Utagawa Hiroshige. (Courtesy Okada Museum of Art)

There is some debate among researchers whether Hiroshige actually traveled any further than Hakone, with some saying that his Fifty-Three Stations works were not based on personal observations. One of his followers wrote that the shogunate ordered him to journey along the Tōkaidō to Kyoto in 1832, but the truth of this is not certain.

Inagaki comments, “For pictures west of Shizuoka, there are more cases where he based material on the source book Tōkaidō meisho zue [Illustrations of Famous Places on the Tōkaidō]. Meanwhile, you can feel the authenticity in the highway scenes up until Hakone, so some say he really walked this part. But there are few records, so it’s just impossible to say for sure.”

Hokusai a Rival?

Seven of the prints in the series feature Mount Fuji. While Hiroshige generally seeks variety with a balance of different seasons and weather, Fuji’s appearances tend to come on winter days.

The morning Fuji seen in the Hara print conveys the peak’s overwhelming scale. While elsewhere in the series, it plays a supporting part, viewed in the distance by travelers, here it takes a central role. Bathed in the morning glow, it stands in the middle of the picture, its summit extending beyond the frame.

The Hara print from Utagawa Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. (Courtesy Okada Museum of Art; appears in September–December exhibition)

A woman hurrying along the road turns at a crane’s cry, and lifts her hat to look up at Mount Fuji. Hiroshige superbly conveys how she is held there for the moment, reluctant to move on. “The ingenious composition emphasizes the sublimity of Mount Fuji in the morning sun,” Inagaki says.

The ukiyo-e master Hokusai was renowned for his prints of Mount Fuji. Hiroshige was more than 30 years younger, but he seems to have had a strong spirit of rivalry. In an introduction to his Fujimi hyakuzu (One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji), he wrote that Hokusai’s emphasis was on the interest of his designs, with Mount Fuji often reduced to just a part in these combinations of features. By contrast, Hiroshige said that his own works were based on sketches of the mountain just as he saw it.

“As an artist seeking to represent reality, the pride in his landscapes comes through,” Inagaki comments.

Gourmet Guidebook

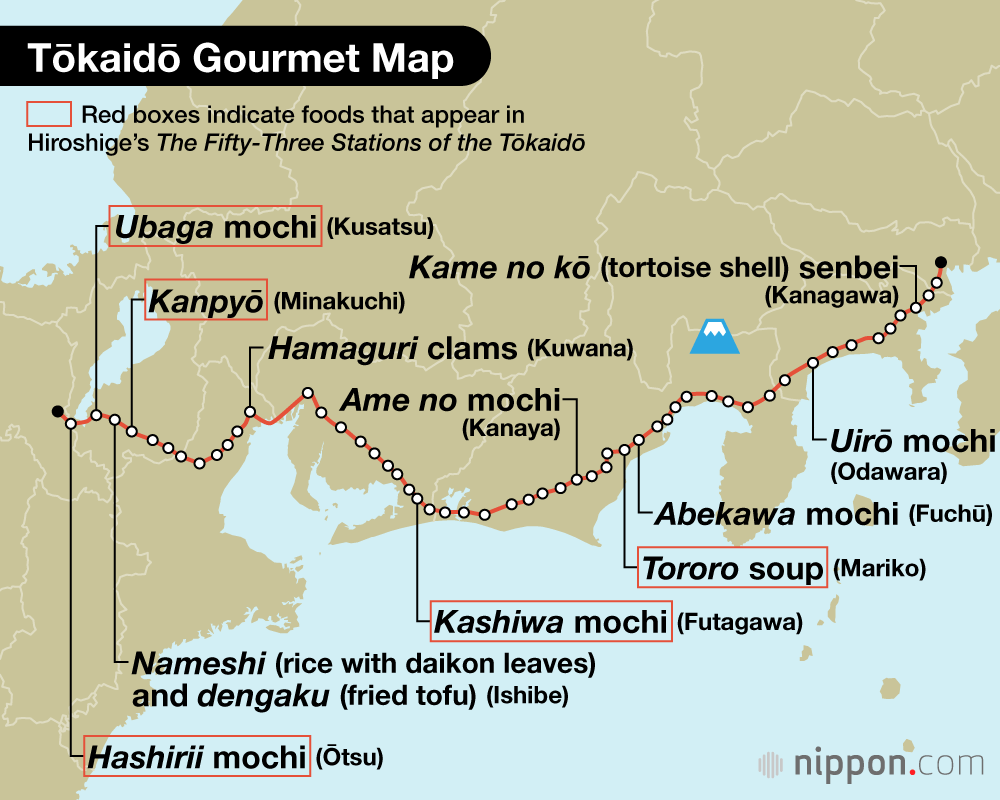

Eating local specialties is one of the joys of travel, and this was no different in the Edo period. Famous foods also appear in The Fifty-Three Stations.

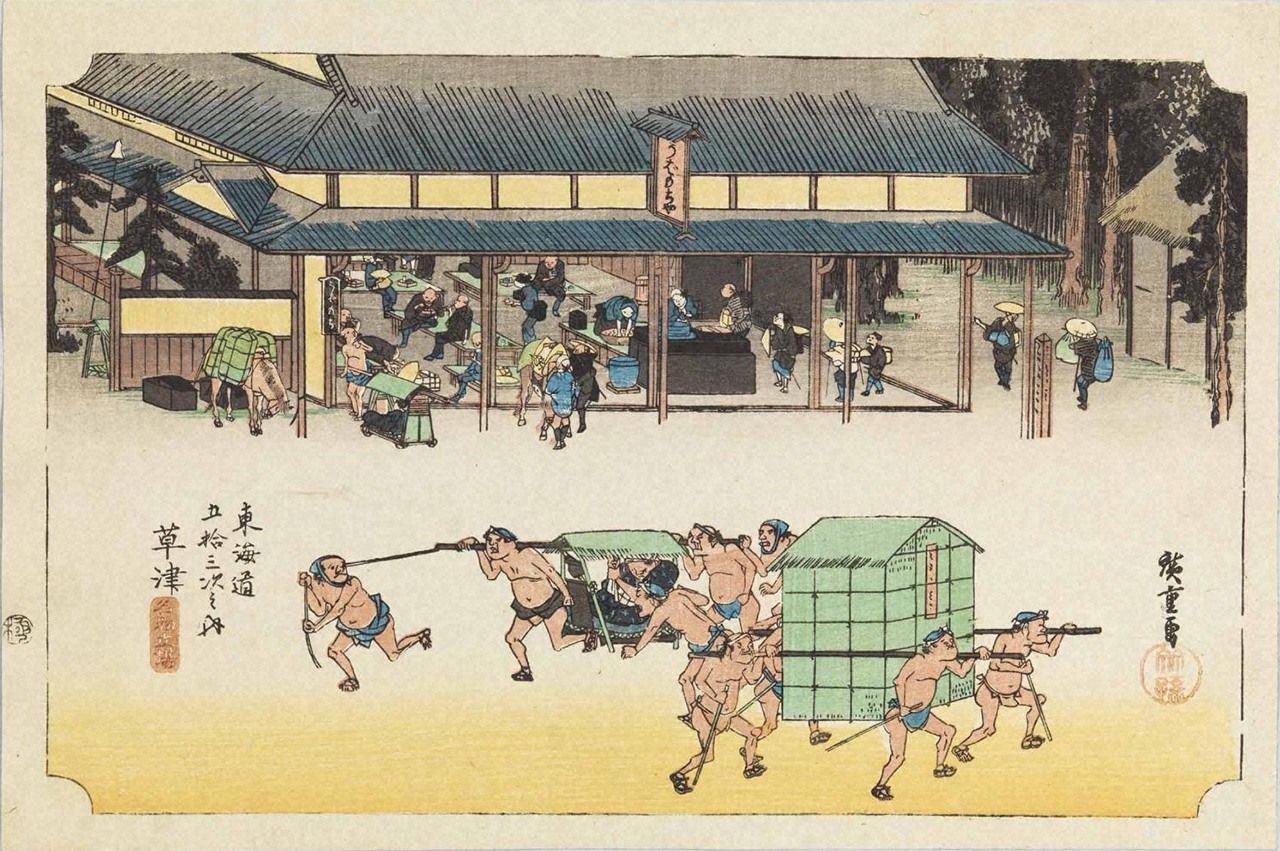

For example, the Kusatsu print shows a post house selling ubaga mochi, or “wet nurse’s mochi,” which is a breast-shaped rice cake wrapped in an bean paste. The delicacy is said to date back to 1569, when a wet nurse for the great-grandson of a vanquished daimyō hid him in her hometown of Kusatsu and earned money to raise him by making mochi snacks and selling them on the street.

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Kusatsu print from The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. (Courtesy Okada Museum of Art; appears in June–September exhibition)

Kusatsu was a transport hub, where the Tōkaidō and another Edo–Kyoto highway, the Nakasendō, crossed over each other after separating at Nihonbashi. In the foreground of the print, four men grip poles, carrying a large piece of luggage. As they move to the right, they are passed by five men hurrying to the left with a litter; the traveler inside holds on tight so he does not tumble out.

The next print is for Ōtsu, the last of the 53 stations before Kyoto, and this time hashirii mochi can be seen on sale. The word hashirii means “gushing spring water,” which is said to have been used when the specialty was first made in 1764. The thin rice cakes filled with smooth bean paste are shaped like swords in reference to a famous swordsmith of the past.

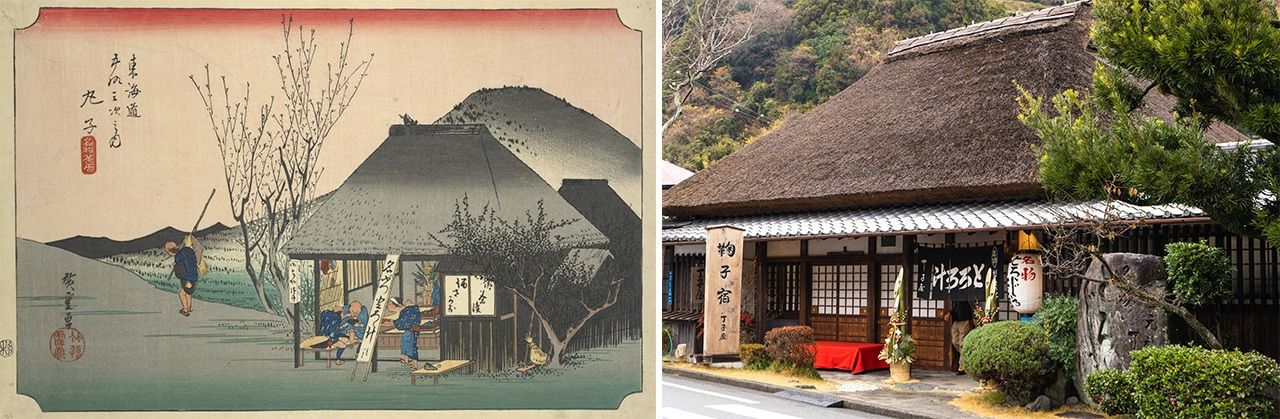

In the Mariko print, two men who look like they might be the comic heroes of Shank’s Mare enjoy the local dish tororo (grated yam) soup with sake. Hiroshige may have taken some inspiration from the hit novel.

Ubaga mochi (at left; courtesy Ubaga Mochiya) and hashirii mochi (at right; courtesy Hashirii Mochi Rōho)

At left, the Mariko print from Utagawa Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō (Courtesy New York Public Library); at right, Chōjiya in Mariko, founded in 1596, which appears in Hiroshige’s print and is still active today. (© Pixta)

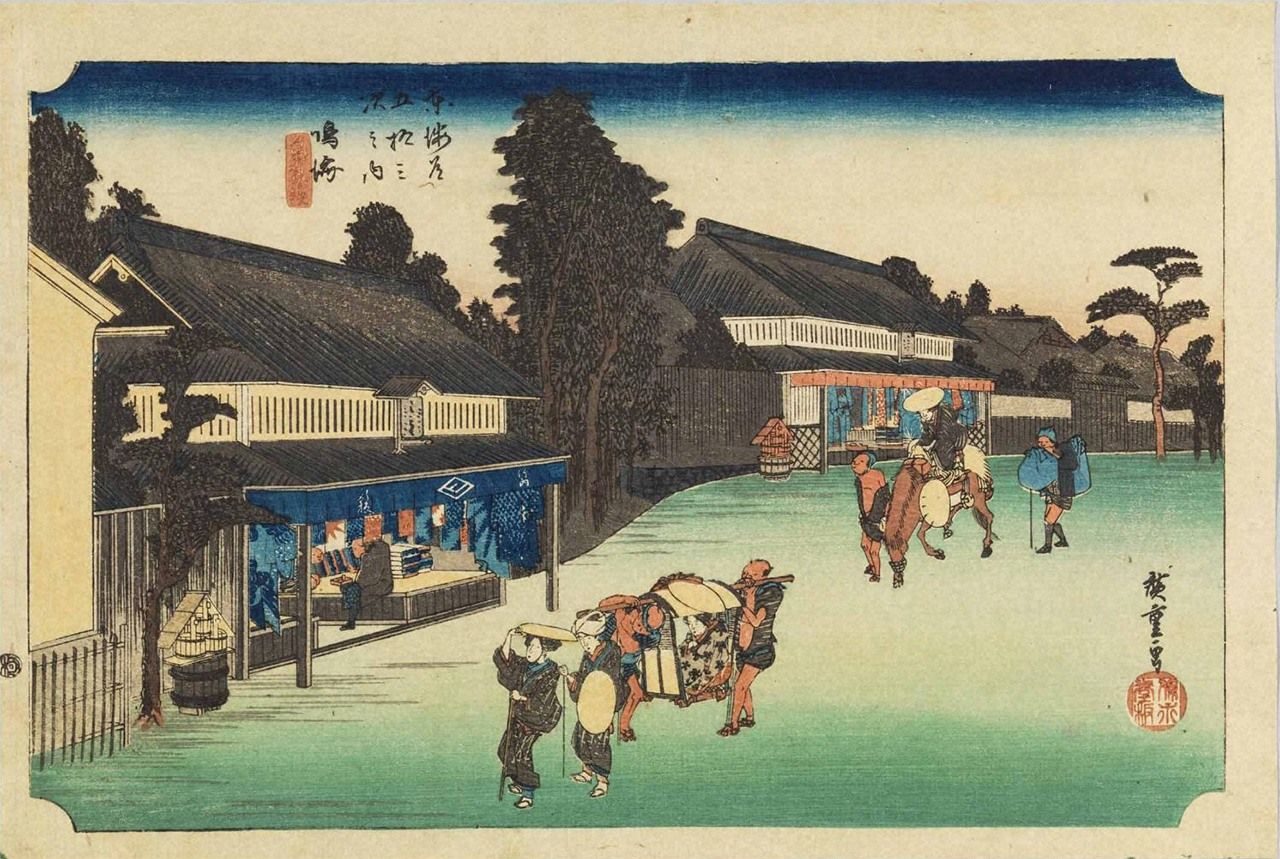

Other local products also feature in the prints. In Hiroshige’s rendering of the Narumi station (located in what is now Nagoya), there is a store selling Arimatsu tie-dyed fabric. Colorful materials are piled up inside the curtain and it looks like a customer is bargaining with the owner. Outside the store, a woman in an elegant kimono is being carried downhill in a palanquin. Perhaps she has bought some fabric herself. This print demonstrates how Hiroshige’s realism can inspire viewers to imagine their own stories.

“Apart from its aesthetic qualities, the Fifty-Three Stations also served as a guidebook,” Inagaki says. “This was probably a big reason that it became so successful.”

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Narumi print from The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. (Courtesy Okada Museum of Art; appears in June–September exhibition)

As well as displaying all 55 prints in The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō, the Okada Museum of Art exhibition includes many other famous works connected with the Tōkaidō, mainly by Edo and Kyoto artists and writers. Among the major names are the potter Ogata Kenzan, Edo artists Sakai Hōitsu and Suzuki Kiitsu, and Kyoto painters Itō Jakuchū and Maruyama Ōkyo.

The exhibition will have two parts, the first running from June 9 to September 12, 2024, and the second from September 13 to December 8. Original works in The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō will only appear in one part, but copies will be on display for prints that are not exhibited.

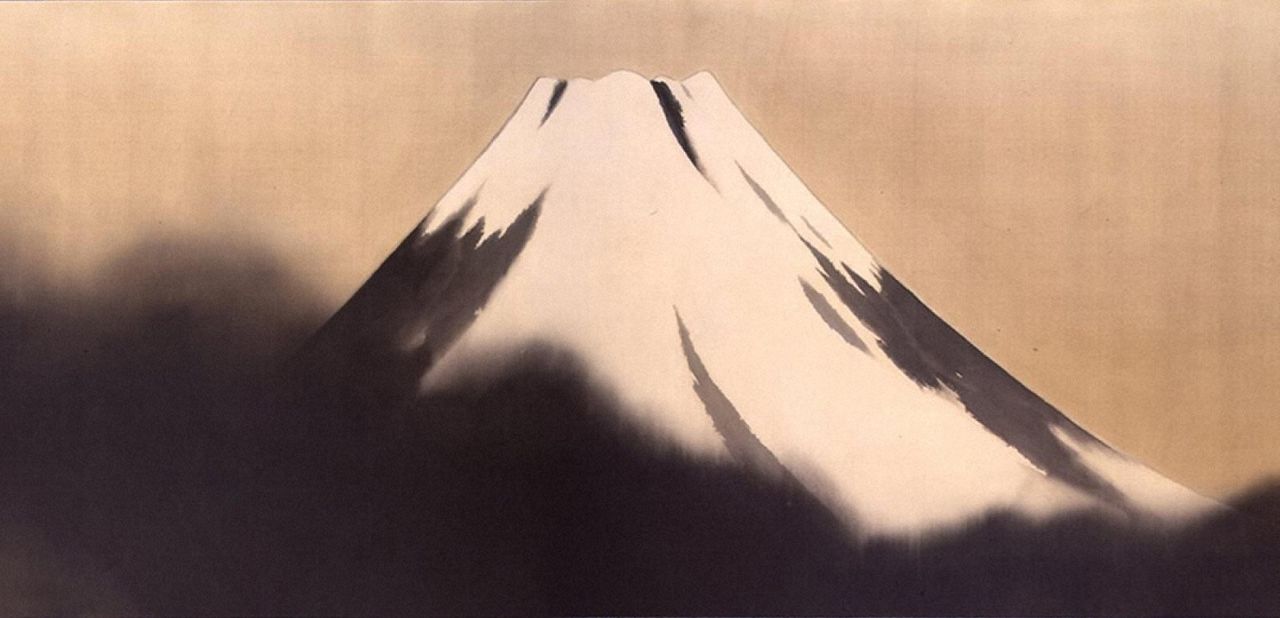

The museum also has a 1926 painting of Mount Fuji by the nihonga master Yokoyama Taikan, which is almost one meter tall and nine meters wide. (Courtesy Okada Museum of Art)

(Originally published in Japanese on June 22, 2024. Banner image: The Kyoto print in Utagawa Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. Courtesy Okada Museum of Art; appears in September–December exhibition.)