The Tōkaidō: Japan’s Most Famous Road

Guide to Japan History Art- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Military Road to Travel Route

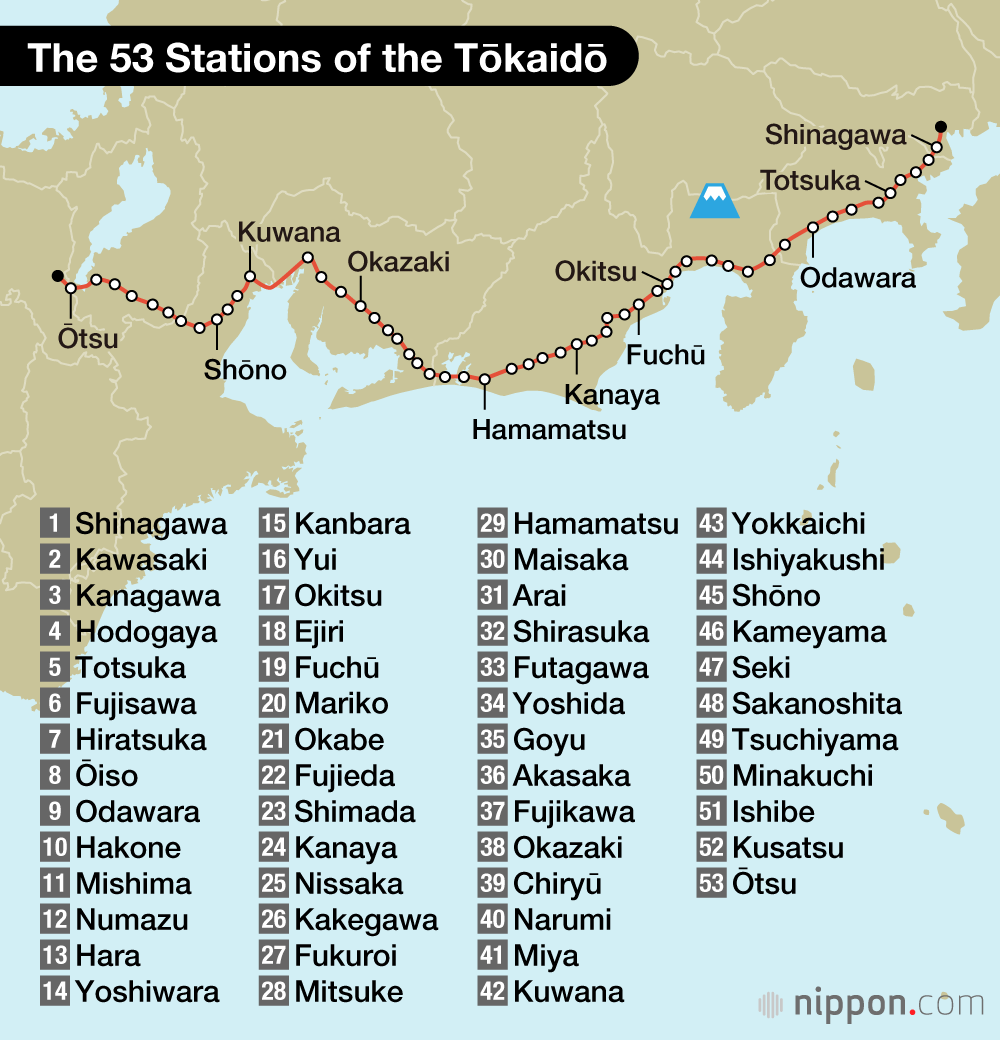

In the Edo period (1603–1868), the Tōkaidō was one of Japan’s Five Highways radiating from the capital of Edo (now Tokyo) and was a major artery connecting the city with Kyoto. The route, named for the administrative area it ran through, had been in use since ancient times, but received a major upgrade in the seventeenth century. This included the addition in 1624 of the last of the road’s famous 53 post stations at Shōno—forty-fifth on the route—in what today is Mie Prefecture.

The fish market at Nihonbashi, the eastern terminus of the Tōkaidō, in a woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige. (Courtesy National Diet Library Digital Collection)

The titular bridge at Nihonbashi was originally made of wood and was rebuilt multiple times due to fire and age. In 1911, it was replaced by a stone bridge, which was obscured when an expressway was built above it in 1963. (© Amano Hisaki)

After his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, Tokugawa Ieyasu set out to secure complete control of the country. Looking to ensure speedy communication between Edo and the imperial court in Kyoto and Osaka, the base of the rival Toyotomi clan, in 1601 he ordered that each of the stations along the Tōkaidō maintain 36 horses for the use of official messengers. Along with its military function, the road assured the safe, steady flow of goods and travelers.

With the introduction of the sankin kōtai system of “alternate attendance,” daimyō from the various domains had to show their allegiance to the shogunate by making regular visits to Edo. They were accompanied by a large entourage that included retainers and porters, with the increased traffic on the Tōkaidō spurring the development of a vast array of accommodations at the highway’s stations that served the varying ranks of travelers. Checkpoints were also introduced for security purposes, and while traffic generally flowed smoothly on the road, authorities created obstacles, such as banning bridges on some rivers, to control traffic.

A daimyō procession crosses the broad Ōi River. Bridges and ferries were banned on the waterway as part of the shogunate’s defense policy. (Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Library digital archive)

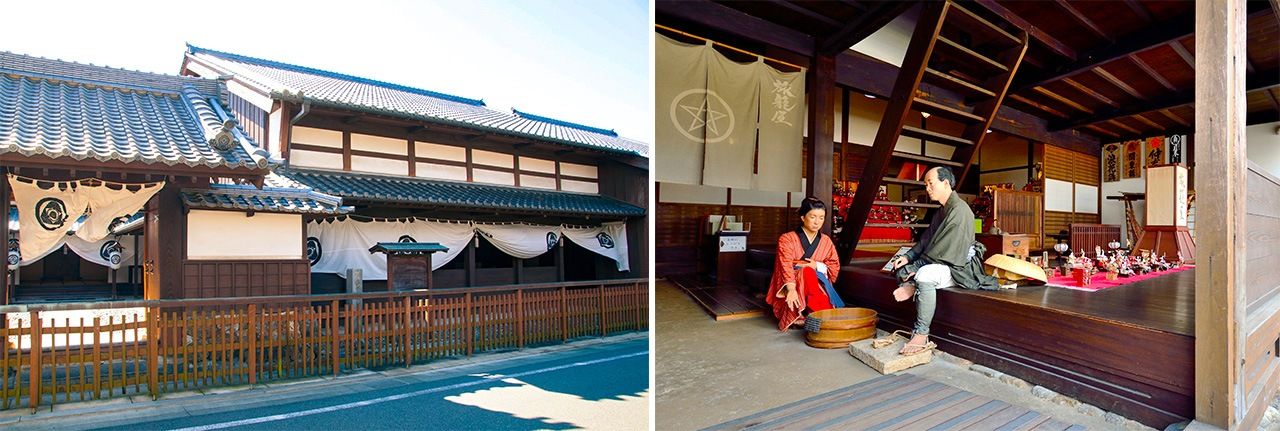

Now a museum, the Futagawa Shuku Honjin (left) in Toyohashi, Aichi Prefecture, was an inn for daimyō and other nobles that operated from 1807 to 1870; the nearby Seimeiya (right) provided accommodation for ordinary travelers. (© Pixta)

As the Edo period settled into a long, peaceful span, the Tōkaidō shifted away from its political and military nature to become a popular travel route for commoners and others making pilgrimages to places like Mount Fuji and Ise Shrine.

Mount Fuji had long been considered sacred, but the Edo period saw a sharp rise in the number of Fuji kō, associations dedicated to climbing Mount Fuji as a religious practice, whose members would journey in large numbers to the peak. Meanwhile, a steady stream of pilgrims to Ise Shrine also traversed the highway, with their numbers swelling on years deemed auspicious for visiting the sanctuary. There were three occasions, around 60 years apart, that were especially favorable, leading to stories of individuals who were unable to participate in the pilgrimage sending their dogs in their place, the canines carrying the funds for the journey with them around their necks.

A group of pilgrims perform the Ise Odori at Ishibe, the fifty-first stop on the highway, depicted in Utagawa Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. (Courtesy New York Public Library)

Fiction and Art

Writer Jippensha Ikku captured the hearts of the travel-loving commoners with his comic novel Tōkaidōchū hizakurige (trans. by Thomas Satchell as Shank’s Mare); the first volume became a bestseller when it was published in 1802. In the work, the two protagonists Yajirobei and Kitahachi blunder their way along the highway to Kyoto in a humorous travel journal incorporating witty descriptions of famous locations, regional foods, and local customs.

Utagawa Hiroshige’s woodblock print series The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō, published in the 1830s, also inspired wanderlust with its lyrical depictions of each of the stops along the road.

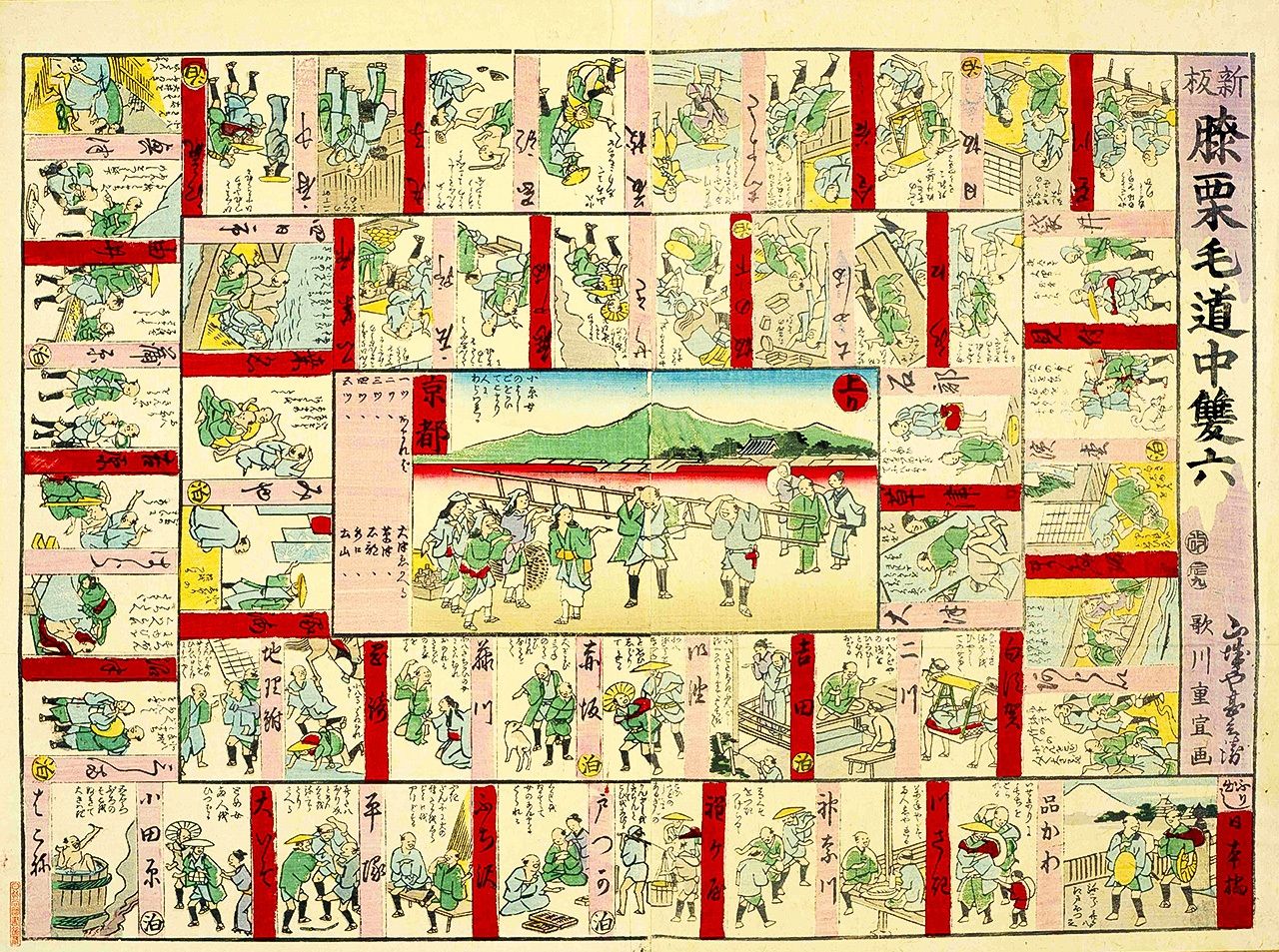

For those yearning to travel but unable to, themed sugoroku board games played with dice offered the chance for vicarious journeys with illustrated information about different stops on the highway.

A sugoroku board game based on Jippensha Ikku’s Shank’s Mare, with illustrations by Utagawa Shigenobu (later Utagawa Hiroshige II). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

A Healthy Pace

Contemporary records and fictional accounts suggest that the journey from the start of the Tōkaidō at Nihonbashi in Edo to its terminus at the Sanjō Ōhashi in Kyoto typically took around 13 to 17 days on foot.

The German doctor Philipp Franz von Siebold, who came to Japan in the late nineteenth century, took around two weeks to get from Kyoto to Edo. The fictional Yajirobei and Kitahachi leave the highway before the end to go to Ise Shrine, but it takes them 12 days to travel the 390 kilometers from Edo to Yokkaichi, the forty-third station. A typical pace of 30 to 40 kilometers a day shows that the ordinary Japanese of the day were healthy walkers.

Incidentally, ukiyo-e and other pictures often show women walking alone or in pairs, indicating that authorities maintained a high level of safety on the highway.

Rapid Communication

Relays of messengers called hikyaku performed a function similar to later postal or telephone services, with the couriers, whose title literally means “flying legs,” traversing the route in lightning-fast three to four days. The shogunate placed official messengers at each station to carry boxes containing letters and packages. There were also dedicated messengers for daimyō as well as private machi hikyaku used by private citizens.

The messenger system continued into the start of the Meiji era (1868–1912), but after the postal service came under government management in 1871, messenger service operators joined together to form a transportation company.

Modern-day ekiden relay races seek to channel the spirit of the hikyaku messengers. The most famous, the Hakone Ekiden in the New Year season, pits university teams against each other on a course that follows the old Tōkaidō for part of the two-day race from Tokyo to Hakone and back again.

A hikyaku messenger dashes through the post station of Hiratsuka in a print from Utagawa Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. (Courtesy New York Public Library)

What to Pack?

In the early nineteenth century, the travel boom, centering on Ise Shrine, spawned a raft of guidebooks. The Ryokō yōjinshū (Precautions for Travelers), for instance, advised travelers to carry items like a brush-and-ink case, a folding fan, needle and thread, a pocket mirror, a lantern, a candle, and a flint and steel fire starter. It also urged readers to bring a rope and hooks, which the work argued were priceless for drying washing at accommodation along the way.

A hit product in the Edo period, Odawara’s famous lanterns were said to protect against evil spirits and could be folded up when not in use and carried inside a kimono. (© Pixta)

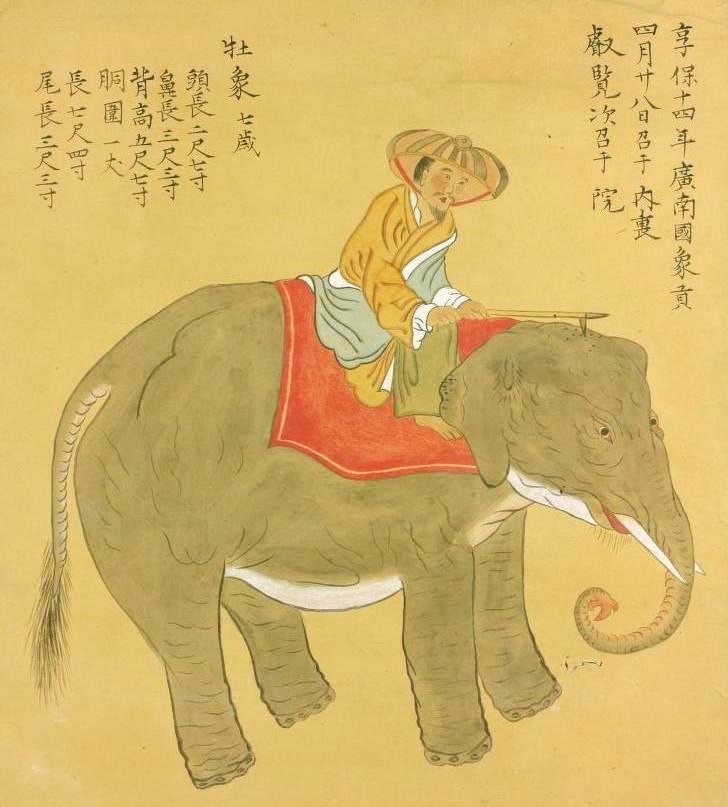

Not all the travelers on the highway were human. There is one memorable account from 1728 of a journey made by an elephant. In that year, a Chinese trader gifted a pair of elephants to Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshimune. The creatures arrived in Nagasaki from what is now Vietnam, and while the female died soon after reaching Japan, the male walked all the way to Edo, stopping at many of the Tōkaidō stations. Yoshimune is said to have marveled at the strange beast, which lived on in the Hamarikyū Gardens until 1742.

A drawing of the elephant that traveled the Tōkaidō highway. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

There was also a famous annual journey, which saw the transportation of Uji tea, grown near Kyoto, in stoneware jars to the shōgun’s household in Edo. In this display of power, even daimyō had to cede the way to shogunate officials carrying the tea, while common residents were prevented from tending their fields and instead had to prostrate themselves before the procession. This gave rise to a satirical children’s song warning to shut the doors when the tea jars were passing, and not to go outside even if called by their parents.

How Many Stations?

While the Tōkaidō is commonly known for its 53 stations, a number of official documents show an additional four post towns between Kyoto and Osaka, bringing the total to 57. The highway was extended as far as Osaka in 1619, incorporating another highway built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

In recent years, some local authorities have attempted to promote the 57-station highway, such as Moriguchi, which was the location of the last station on the extended route. However, the fame of Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō and other factors have kept the association with the original number strong.

The Station at Shinagawa

It is about eight kilometers from Nihonbashi to the first station at Shinagawa, which was adjacent to the sea in the Edo period but has moved inland as reclamation projects expanded the boarders of the city into the bay.

The area around today’s Shinagawa Station, now a major rail hub, is a bustling business district full of skyscrapers. However, around a 15-minute walk south of the area, near Kita-Shinagawa Station, is the location of the old Shinagawa post station. Stretching some 3.6 kilometers south along a road leading to Suzugamori, the site of a notorious execution grounds, it retains a hint of the Tōkaidō of yesteryear.

The post station of Shinagawa in Utagawa Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. (Courtesy New York Public Library)

Kita-Shinagawa Hondōri, is a curving shopping street that once ran along the coast. (© Pixta)

Satō Ryōta, the proprietor of Kaido Books & Coffee located on the Kita-Shinagawa Hondōri shopping street is working to reinvigorate interest in the street. He is joined by Tanaka Yoshimi, a former secondhand bookshop owner and enthusiastic walker of Japan’s old highways. Above the café is a space with around 10,000 books about Japan’s ancient highways, walking, and travel that also doubles as a venue for presentation and other events held in association with the local authority’s tourism division.

The short walk to the sea reveals lines of yakatabune pleasure boats and fishing vessels set against a backdrop of soaring buildings, creating an endearing scene combining old and new.

Kaido Books & Coffee stands out with its red bricks (left); the view across the water. (© Amano Hisaki)

(Originally published in Japanese on June 21, 2024. Banner image: Nihonbashi in Utagawa Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō depicts a daimyō’s procession crossing the bridge. Courtesy New York Public Library.)