Hokusai’s “Great Wave”: From Edo Period Mass Culture to the ¥1,000 Bill

Arts Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Wave that Swept the World

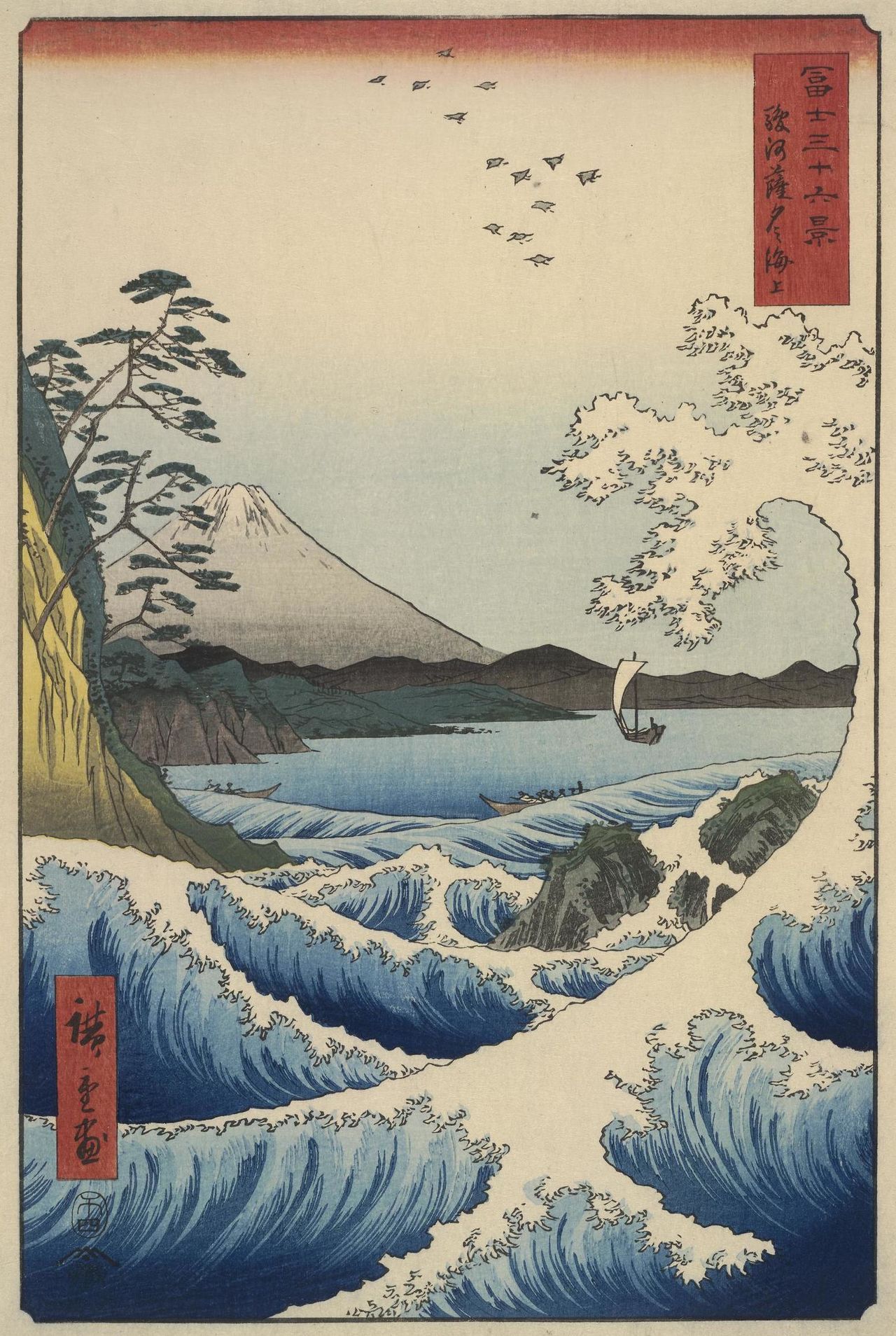

Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji is a series of ukiyo-e prints by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), who was in his seventies when he produced the work. Coinciding with a surge of interest in pilgrimages to the sacred mountain among the townspeople of Edo (now Tokyo), the series was an immediate hit, leading to the addition of 10 more prints. The series cemented the place of landscape pictures of “famous places” as a popular genre and inspired a galaxy of talented followers, including Utagawa Hiroshige. Hokusai’s masterpiece was a milestone in Japanese artistic history—and one whose impact was felt almost immediately far beyond Japan.

The series drew its inspiration from Fuji, the mountain that has been a symbol of Japan for centuries, was added to UNESCO’s World Heritage list in 2013, and has adorned the pages of Japanese passports since . Made up of masterfully composed pictures, the series depicts the mountain from near and far, but one image in particular has always made a special impression on people around the world: the view of the mountain as seen from beneath the Great Wave off Kanagawa. At least partly because of its international celebrity, this print was chosen as the design for the new ¥1,000 banknotes entering circulation in July 2024.

Katsushika Hokusai, the Great Wave off Kanagawa, from Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (around 1832). (Courtesy Sumida Hokusai Museum)

The print shows three fishing boats being tossed on turbulent seas and apparently about to be swallowed by a mighty wave, as the lofty peak of the sacred mountain looks on aloof and serene from a distance. The picture, known internationally as The Great Wave, has appeared on a French stamp and on the walls of a giant housing complex in Moscow. It has become a ubiquitous part of global mass culture, familiar to millions of people who have never visited Japan or heard the name of the artist.

Prices on the international art market reflect the reputation and popularity of Hokusai’s work. In 2024, a complete set of 46 prints from the series sold at auction for $3.6 million in the United States. Perhaps even more impressively, the year before that a single print of the Great Wave sold for $2.8 million. This was an early print made before the woodblocks started to erode from repeated use: first-generation prints are prized by collectors for the clarity and definition. Even so, this was a remarkable price for a print that circulates in hundreds of contemporary copies.

Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji on display at a New York auction house on September 17, 2023. (© Jiji)

The Wave’s Impact on the European Avant-Garde

The international popularity of Hokusai’s wave can be traced back to the Paris Exposition of 1867. The occasion marked modern Japan’s “debut” on the world stage, after more than two centuries of seclusion from international affairs. The exhibits of ukiyo-e and other artworks appealed to Europeans by the exoticism of their subjects and fresh style. Japanese art attracted further interest at subsequent exhibitions in 1878, 1889, and 1900, inspiring the japonisme movement.

Academic painting in nineteenth-century France was governed by a strict hierarchy of genres, headed by historical paintings of Biblical and mythical scenes, followed by portraiture and scenes of daily life. Landscapes and still-life pictures were not seen as worthy of serious critical consideration. But ukiyo-e prints appealed to ordinary people because of the immediacy of their subjects, which were often things drawn from nature, like flowers and insects. The pictures also inspired avant-garde artists, who incorporated Japanese ideas and techniques, having a formative influence on the emerging Impressionist movement.

Hokusai’s Wave, in which the huge wave dominates the composition, had a particularly strong impact on Western artists. Vincent Van Gogh was an avid collector of Japanese prints. A letter to his brother Theo in 1888, contains a vivid description of the picture: “Hokusai makes you cry out the same thing — but in his case with his lines, his drawing, since in your letter you say to yourself: these waves are claws, the boat is caught in them, you can feel it.”

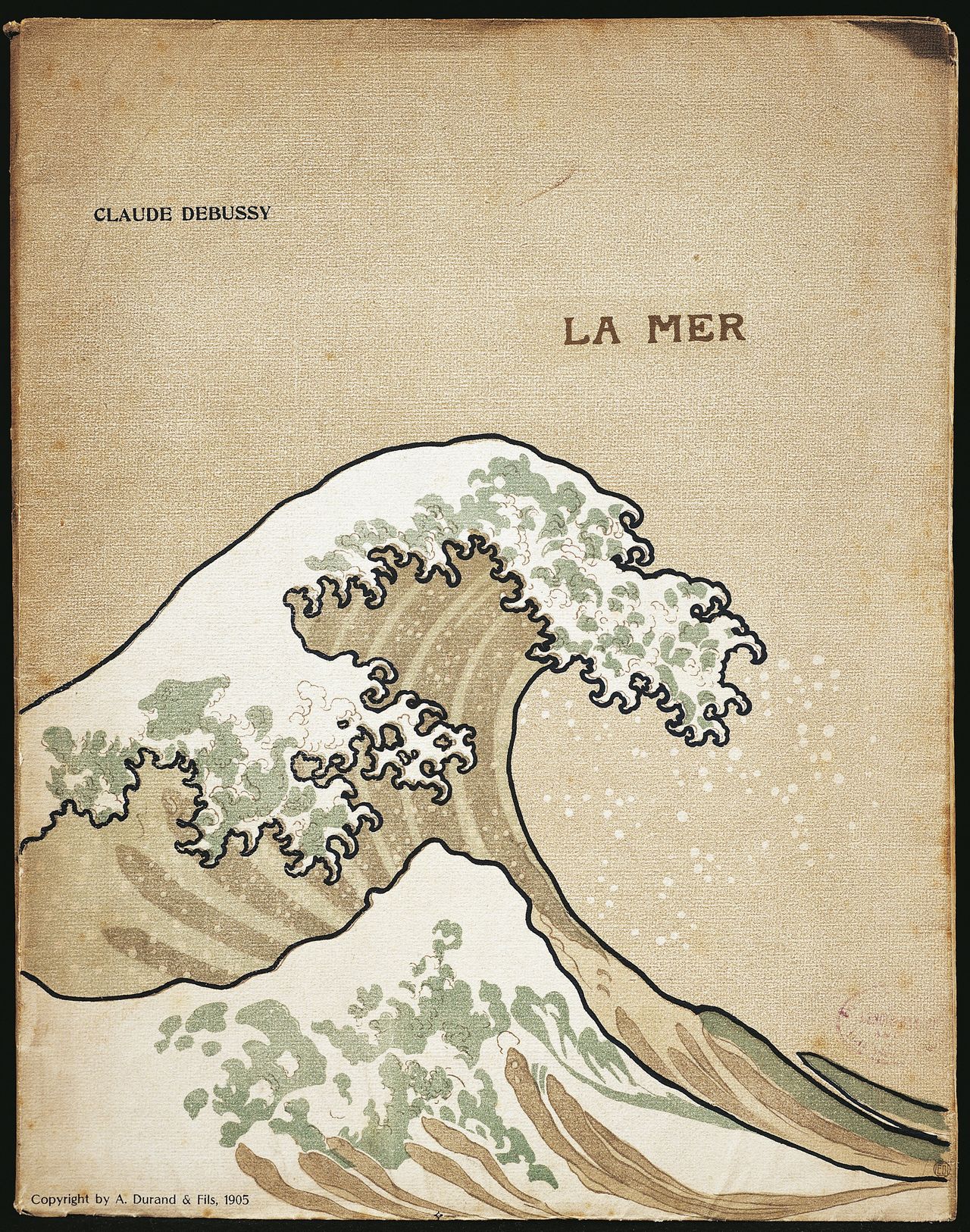

The French sculptor Camille Claudel produced a piece that combined a towering wave with three classical beauties bathing on a beach. The first edition of the music score for Claude Debussy’s La Mer carried a picture of a wave obviously inspired by Hokusai.

The first edition of the score for La Mer, by Claude Debussy (1905). (© Dea/G. Dagli Orti/De Agostini via Getty Images)

Hokusai Comes Home

Originally, ukiyo-e prints were cheap entertainment that sold for around the same price as a bowl of soba noodles, so those who produced them did not have the same concept of “art” as today. Their business model was to produce and sell in bulk, as widely as possible. Artists and their publishers therefore followed all the popular trends, producing pictures of popular kabuki actors and beauties (similar to “pop idol” merchandise today), poster-like pictures of famous places, and the unabashedly pornographic shunga or “spring pictures.”

But after the forced opening up of Japan to the Western powers from the 1850s, opening the country to a flood of foreign influences, the mood changed. People started to look down on the popular culture of the Edo period (1603–1868) as unsophisticated, feudalistic, and embarrassing. Unlike in the West, where the japonisme movement sustained a fascination for all things Japanese for some time, in Japan itself the interest in ukiyo-e soon faded, and collections of works by previously popular artists were scattered overseas. Hokusai’s works were no exception—by the time of the Meiji Restoration his prints were being used as packing material for more valuable goods shipped overseas. It was only following World War II that people in Japan recognized the artistic value of the prints again, after they became famous and prized overseas.

In 1999, 150 years after his birth, Hokusai was chosen by Life magazine as one of the “100 People of the Millennium”—the only Japanese person on the list. His international reputation has continued to soar in the twenty-first century, and major exhibitions of Hokusai’s work have been held at the Grand Palais in Paris (in 2014), the British Museum (2017), and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (2023), drawing large crowds.

In Japan too there have been a number of repeated exhibitions of his work in recent years, and many fine prints have returned from overseas. It is fair to say that the reevaluation of Hokusai’s importance in his homeland has been due in large measure to the foreign admirers who collected and preserved his work.

Some 350,000 people visited the Hokusai exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris. Picture from September 29, 2014. (© Reuters)

The International Roots of the Great Wave

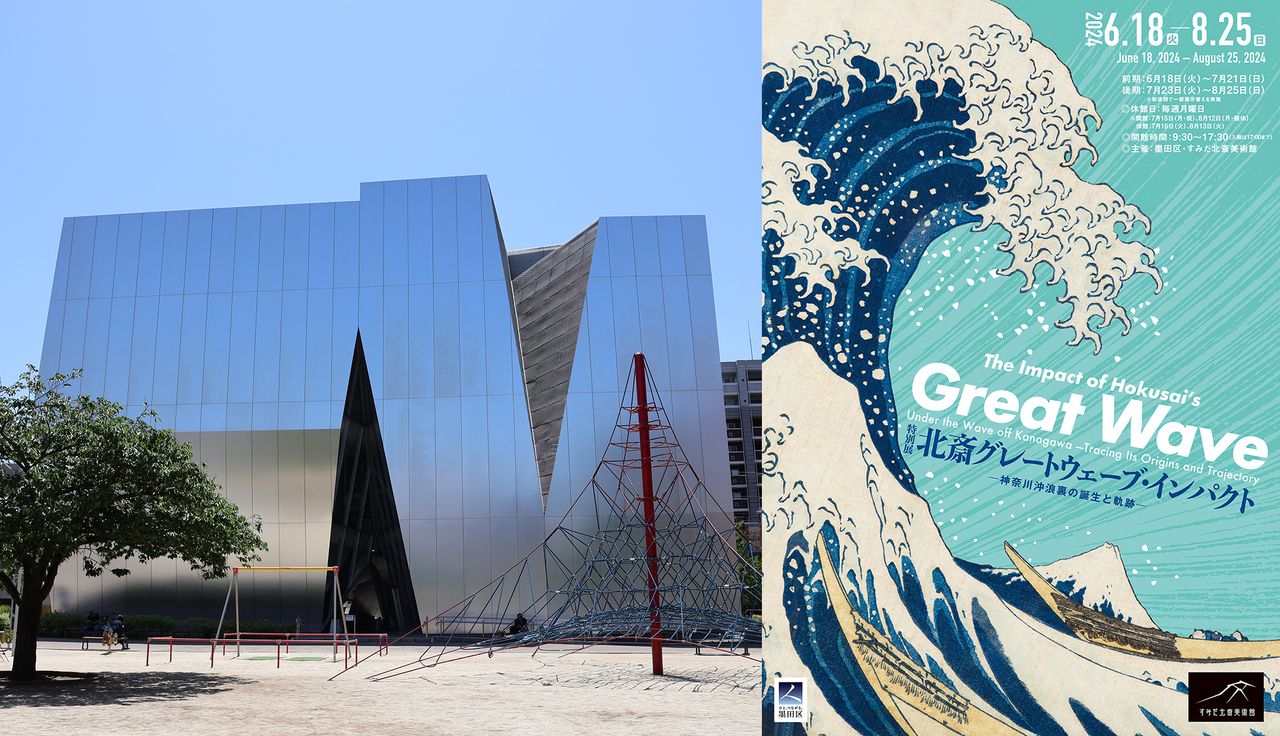

Why has this one picture in particular become so popular with people outside Japan? One reason may be that Hokusai himself was influenced by non-Japanese art, says Okuda Atsuko, chief curator at the Sumida Hokusai Museum in Sumida, Tokyo. Okuda recently helped organize a major exhibition on the picture: The Impact of Hokusai’s Great Wave, which runs until August 25, 2024.

Left: The Sumida Hokusai Museum, located close to where the artist was born, is popular with international visitors; (© Nippon.com). Right: A poster advertising the Great Wave exhibition, which runs from June 18 to August 25 (Courtesy Sumida Hokusai Museum).

Perhaps the most striking thing about the print is its stunning use of vivid blue. This was made possible by “Prussian blue,” invented in Germany in the eighteenth century. In Japan, this pigment was known as “Bero-ai” (Bero from Berlin, ai means indigo), and this new import made it possible for Hokusai to produce blues that were fresher and more eye-catching than anything people had seen before.

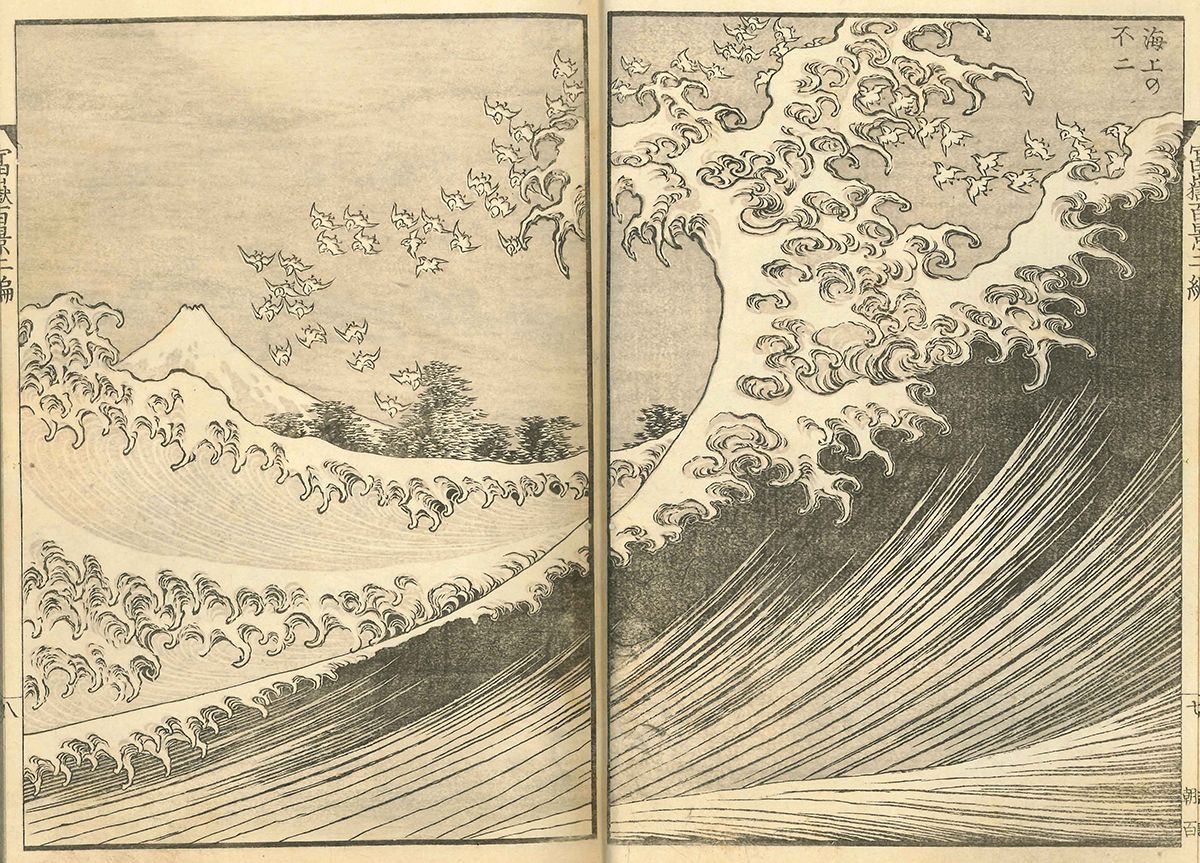

Hokusai’s prints of Fuji also draw on Western-style perspective. In the famous picture of the wave, the frame is skillfully composed to draw the viewer’s eye naturally from the wave that dominates the front of the picture to Mount Fuji further back. Okuda compares the famous print to a version of the same subject, produced around 30 years before, depicting a view of the sea off Honmoku in Kanagawa. “This earlier work already shows signs of this developing sense of depth and perspective,” she says.

Sea off Honmoku in Kanagawa, the “prototype” for the famous wave picture (1804–07). (Courtesy Sumida Hokusai Museum)

Accurate and detailed depiction of waves was one of the calling cards of the Rinpa school of painting to which Hokusai belonged in the early years of his career. This school played an important role in developing the brilliant, colorful yamato-e style of Japanese painting, which often dealt with subjects from nature. Hokusai also learned from the realism of Chinese paintings of birds and flowers (huaniao-hua), effectively using these techniques to capture the teetering head of the towering wave about to collapse into the spray.

Hokusai dedicated his life to his art. Over the course of his 88 years, he moved house 93 times, creating incessantly wherever he went. When he died, he left more than 30,000 artworks. He referred to himself as a “demon of painting,” and it was perhaps this voracious, demonic appetite for art that allowed him to absorb techniques from Japanese, Chinese, and Western traditions and combine them to produce works that show such a remarkable balance between realism and exaggeration for effect.

In total, Hokusai produced 102 images of Mount Fuji. Fuji Above the Sea (1834) from One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. Sumida Hokusai Museum. On view throughout the exhibition. (Courtesy Sumida Hokusai Museum)

Utagawa Hiroshige, The Sea at Satta, Suruga Province (1858), a late-period homage by a master printmaker to his great predecessor. (Courtesy the British Museum)

Hokusai’s wave has become a classic that has inspired countless homages and parodies. Artists continued to borrow from its style and composition to the present. At one stage, Hokusai’s works were treated as worthless scraps of paper. A century and a half later, they sell for millions of dollars. And now his most famous image will be printed on the national currency, to be seen by millions of people every day. How pleased the artist would be to see the impact that his great wave has had, constantly changing like the sea, and capturing the imagination of so many people around the world.

Inside the exhibition space at the Sumida Hokusai Museum, Tokyo (© Nippon.com)

For more details of the exhibition, see the website of the Sumida Hokusai Museum:

https://hokusai-museum.jp/?lang=en

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The reverse of the new 1,000-yen banknote (© Stanislav Kogiku / SOPA Images via Reuters Connect) at center, surrounded by, clockwise from top left: the Hokusai exhibition at the British Museum, January 10, 2017 (© Carl Court/Getty Images); Caumont Centre d’Art, Aix-en-Provence, November 6, 2019 (© AFP, Jiji); Hokusai’s wave in Lego in Denmark on December 28, 2022 (© LEGO Group/Cover Images via Reuters Connect). Collage by Nippon.com.)