Super Speed from a Super Cub: The Fastest-Ever Version of the Most Popular Vehicle Ever

Technology Sports- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Motor Sport Drama in the High Desert

At a dried-up salt lake in Utah, on a high desert plain where temperatures reach over 40 degrees Celsius in the summer, an annual event attracts speed freaks from all around the world: the Bonneville Motorcycle Speed Trials. Here a 16-kilometer-long straight course, built on the Bonneville Salt Flats, hosts a maximum speed certification competition every August, recognized by both the US National Motorcycle Association and the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme.

Divided into dozens of categories based on items such as engine type, displacement, and fuel type, over 200 teams from all over the world will gather to compete. Vehicles range from 50 cc motorcycles to cars with rocket engines.

There is no prize money even when someone wins, but people continue to compete in this speed contest. It has a history that spans over 110 years, and people compete with the sole aim of winning the title of “world’s fastest” for their category of choice.

The World’s Fastest Indian, a 2005 film starring Anthony Hopkins, is based on the true story of Burt Munro, the legendary rider from New Zealand who achieved the world’s fastest speed (in the under 1,000 cc motorcycle category) in 1962 at the age of 63.

There is a Japanese man who reminds us of Munro’s challenge. Chikakane Takushi is a film director from Kobe, Hyōgo Prefecture. Born in March 1962, Chikakane first raced in Bonneville when he was 56 years old. Since then, he has set six world speed records and continues to push himself to break even more.

A “Magic Modification” of Honda Sōichirō's Super Cub

“Ever since I was little, I admired Horie Kenichi,” says Chikakane, referring to a local ocean adventurer living in Ashiya, Hyōgo Prefecture. “He was older than me, and hailed from my hometown. He crossed the world’s widest ocean, the Pacific, in the world’s smallest yacht. I always wanted to try such a small, but great, adventure myself.”

When he was 16, Chikakane got his motorcycle license and became obsessed with road racing. But when he was 23, he fell during a race and broke 13 bones, including some in his neck and spine. It took him two and a half years to fully recover, and he was forced to retire from racing.

The memoirs he wrote during his hospital stay became quite popular, and he decided to become a writer. Afterward he expanded the scope of his work to include stints as a television writer and film director.

The impetus for his Bonneville challenge came from his second film, the 2016 Kiriko no uta, which delves into the world of small-scale, high-quality Japanese manufacturing. While doing research at a metal-processing company in Tokyo’s shitamachi area, he became fascinated by the amazing level of Japanese craftsmanship.

It was then that he set his new goal: to use the company’s technology to “magically modify” the 50 cc engine in a Honda Super Cub two-wheeler and try to achieve the world’s fastest speed at Bonneville.

The Honda Super Cub (a 2022 model pictured here) is the world’s best-selling motor vehicle of any kind. The first model debuted in 1958, and cumulative global production reached 100 million units in 2017. (© Honda)

The Super Cub is a symbol of Made in Japan. It was made by Honda Sōichirō, sometimes called the “Edison of the Orient.” The basic engine design of the bike, often used to deliver newspapers and mail, is around 50 years old, and the maximum output is only 3.7 horsepower. Regardless, Chikakane decided to stick with this four-stroke, air cooled engine for his endeavor.

“There’s no point in doing something that anyone can do. We set the fastest record with the most difficult mechanism and most unfavorable engine. ‘Made in Japan’ has made the seemingly impossible possible.”

Engineers from about 30 companies, mainly in the precision and fine metal processing industries, were captivated by Chikakane’s passion and offered to support him.

The main sponsor, NS Tool, is a leading manufacturer of small-diameter end mills, boasting the technology to carve letters into a single strand of hair using tools with an outer diameter of just 0.01 mm. These blades are essential for the fine machining of metal parts, and the company is a behind-the-scenes supporter of Japanese manufacturing.

“It’s not just anyone who could come up with the idea of putting a turbocharger on a 50 cc engine with the goal of maximum speed. Chikakane’s aim to create the world’s smallest and fastest motorbike matched our ideals,” recalls President Gotō Kōji.

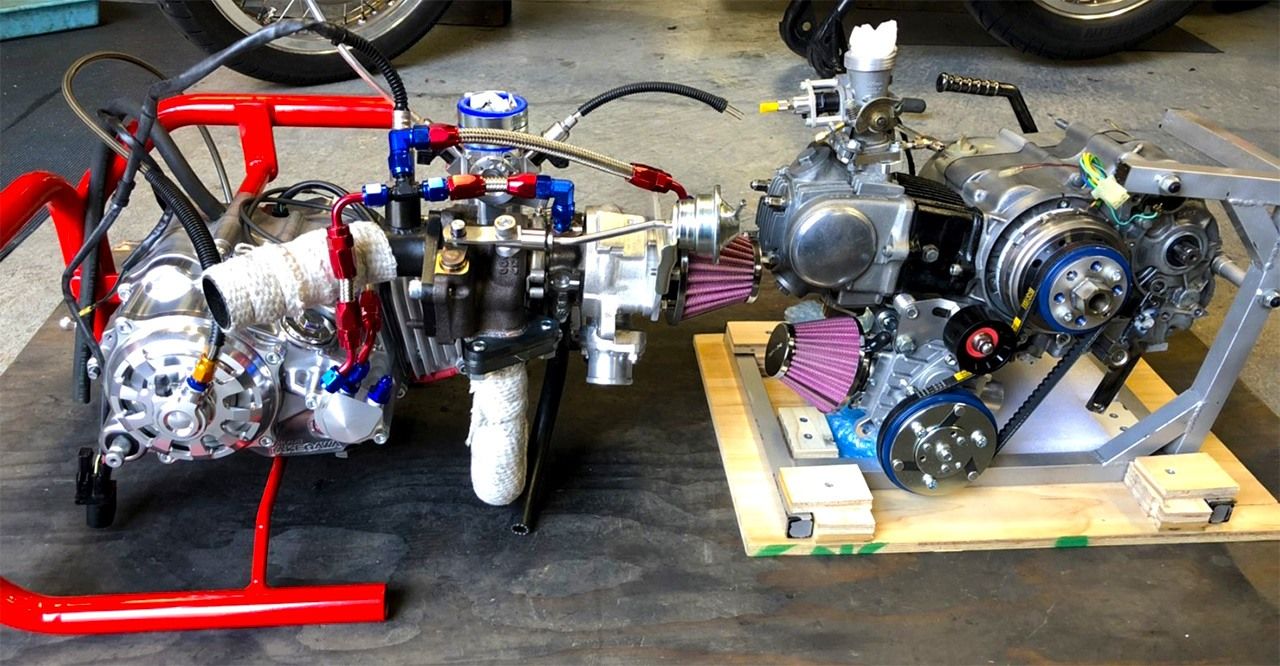

In 2017, a group of highly skilled engineers assembled the latest technology and materials to take on the Bonneville challenge. (Courtesy of Chikakane Takushi)

The challenge involved a two-year plan. In the first year, 2018, the team focused on collecting basic data and entered the 125 cc class, avoiding the lowest 50 cc class, in which there is a higher risk of being knocked out of a race.

The most ingenious design was put into the cowling, which is the key to aerodynamic performance. Knowledge on fluid resistance was accumulated through the development of speedboats, yachts, and racing canoes.

The motorbike recorded an average speed of 153.73 km/h and a top speed of 165.30 km/h. It set this record while completing the course 25 times in a row, earning it the title of “the world’s fastest Cub.”

The NSX-01, a machine designed to resemble a fish, was nicknamed the “Orange Tuna” at Bonneville and attracted a lot of attention. (Courtesy of Chikakane Takushi)

An Unprecedented Take on a 50 cc Classic

However, with this packaging, it would be impossible to break the 50 cc world record. Two major changes were needed.

The first was the engine. At Bonneville, where the air is thin and the temperature is high, power loss is unavoidable with a normal engine, making a supercharger essential. However, supercharging a small engine is extremely difficult, and no manufacturer in the world had succeeded in putting such a miniaturized turbodevicecharger into practical use.

The team that took on this difficult challenge was FC Design, a Hiroshima-based company that helped create the Fancy Carol, which took Guinness World Records in 2003 and 2004 for its fuel economy. There were no commercially available intercoolers to cool the air pressurized by the turbocharger, so with the cooperation of Yamato Radiator in Edogawa, Tokyo, a prototype was made and remade eight times.

The world’s smallest supercharged 50 cc engine. (© Chikakane Takushi)

The other change was to the body design. To minimize air resistance, the design plan prepared by Professor Haneda Takashi of the Shizuoka University of Art and Culture had the rider in a prone, head-first position like that taken by skeleton sled racers.

The unprecedented motorbike, the NSX-51, encountered unexpected trouble during the actual race, when the engine would not start. Fortunately, the team got it working just before the race deadline, and Chikakane put everything on the line in his first and only time attack.

Following a two-mile stretch to accelerate to top speed, racers enter the timed zone, a one-mile stretch over which their vehicles are clocked for speed. As Chikakane entered the measured section in his 2019 outing, he exhaled and kept from breathing in to avoid inflating his lungs and increasing air resistance with a higher back position. Measuring the distance racing by below him, he counted “one, two, three . . .” through the end of the measured section. At the count of 50, he at last lifted his head and took a quick breath.

The biggest problems to overcome on the slick surface of the salt flat are ruts left by fallen vehicles and fierce crosswinds. (Courtesy of Chikakane Takushi)

A Perfect Farewell for a Vanishing Legend

The official timekeeper beside the course gave a thumbs up, and soon Chikakane had the good news—an average speed of 101.77 km/h and a top speed of 128.63 km/h. A new world record for the 50 cc class!

However, shortly after that moment of joy, a feeling of disappointment began to well up inside. Due to engine trouble, the bike couldn’t open its throttle fully, and it was only able to complete one lap. Next year it would show its true worth, he vowed.

But this was not to be. The event was canceled in 2020 due to COVID-19. In 2021, disruptions to shipping logistics caused by the pandemic delayed transportation of the machines, and they did not arrive in time for the start of the race. In 2022, the decision was made to cancel the event before the team even traveled to the United States due to heavy, abnormal rainfall. The race was also canceled in 2023 due to Hurricane Hillary, which made landfall in Southern California. It was the first time a hurricane struck that area in 84 years.

“If only we could race, we’d be sure to break the world record,” was Chikakane’s constant thought for the four years that COVID-19 and abnormal weather kept him and his team from their goal.

At a test held at the Ogatamura Solar Sports Line circuit in Ogata, Akita Prefecture, in November 2023, Chikakane recorded an average speed of 117.05 km/h, 15 km/h faster than his own world record set at Bonneville, although this was unofficial.

For safety reasons, the Akita tests were conducted with engine speeds kept low, and the timed distance was 1,000 meters, 600 meters shorter than the mile-long track of Bonneville. Given that this record was achieved under unfavorable conditions, the team felt confident about their chances in the actual race. (Courtesy of Chikakane Takushi)

There is a reason why Chikakane is determined to take on the Bonneville challenge.

Amid the global trend toward reducing CO2 emissions, Japan’s pride and joy, small, high-performance motorcycles, are also becoming increasingly electrified. The 50 cc model Super Cub no longer meets increasingly stringent exhaust gas regulations, and its production will end in 2025.

“I want to create a record that my rivals will never be able to beat, so that this symbol of Made in Japan, which is destined to disappear, can have the best possible final farewell,” says the racer.

Chikakane Takushi is fired up to break the world record he has held for four years. (Courtesy of Chikakane Takushi)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Team members including Chikakane Takushi, standing at center, pose for a commemorative photo after winning a total of six titles in the 125 cc and 50 cc classes at the Bonneville Motorcycle Speed Trials held in Utah in August 2019. Courtesy of Chikakane Takushi.)