Government Cracks Down on Rampant Shellfish Poaching

Politics Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Industry Up in Arms

The changing marine environment and the warming of the oceans in recent years have adversely affected Japanese fisheries. Amid a decline in fish and shellfish production, Japan’s national and local governments alike are calling strongly for nonfisheries operators—that is, the general public—to comply with the rules governing the catching of fish and shellfish in coastal areas. With no end in sight to poaching, illegal fishing has become a resource management issue.

“Who owns the sea?” you might ask. The answer: no one. Japan’s Supreme Court has ruled that no entity can own the sea or create property rights on its surface. But that is not to say that anyone is free to catch fish and shellfish willy-nilly. In terms of the exploitation of marine resources, fisheries cooperatives and operators are granted licenses to fish by either the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries or the prefectural governor. In other words, the catching of fish or collection of shellfish in the sea by unlicensed persons can infringe on the rights of legitimate fishing operators.

In addition to prohibitions under the Fishery Act on the collection of abalone, sea cucumber, and the like, regulations created by individual prefectures also prohibit the gathering of shellfish in prohibited areas, as well as the use of certain equipment. Conduct that does not comply with relevant laws or regulations is classified as poaching, and offenders are subject to significant fines or imprisonment. The same penalties apply to overseas nationals as well, “irrespective of whether they are tourists on short-term visits, or long-term residents who are studying or working in Japan,” says the Fisheries Agency.

Illegal gathering of abalone carries a maximum fine of ¥30 million. (© Kawamoto Daigo)

Most Offenders Not Commercial Fishermen

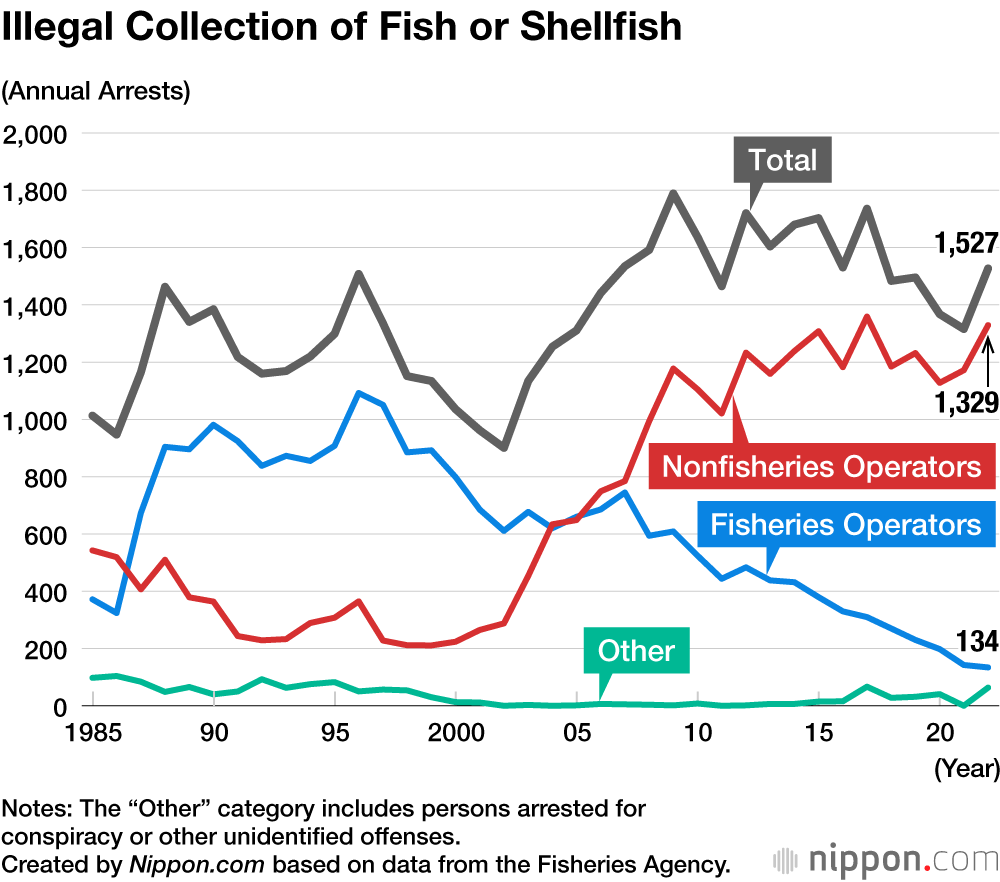

According to provisional statistics published by the Fisheries Agency, the number of people charged with poaching in 2022 under fishing-related laws or regulations was 1,527, which is a 16% increase on the year before. While there was a period of around five years during which reported incidents of poaching declined, it is once again on the rise, and has reached levels rarely seen in recent decades. Obviously, only a fraction of poachers are arrested, so the actual incidence of poaching is believed to be many times greater.

What is interesting is whether or not those arrested for poaching are commercial fishermen. Since 2004, the number of nonfisheries operators arrested for illegal fishing has climbed considerably, while the number of commercial fishermen breaking the law has fallen. Currently, the majority of those arrested are nonfisheries operators, a group that in 2022 represented 1,329 cases—nearly 90% of the total.

The Fisheries Agency believes that there is a heightened awareness of the importance of resource management among commercial fishermen, which contrasts with a lack of awareness by the general public that poaching is wrong, resulting in adverse effects on maritime resources. The Agency is joining forces with local governmental and other bodies to spread the message about poaching.

New Law Provides for Larger Fines

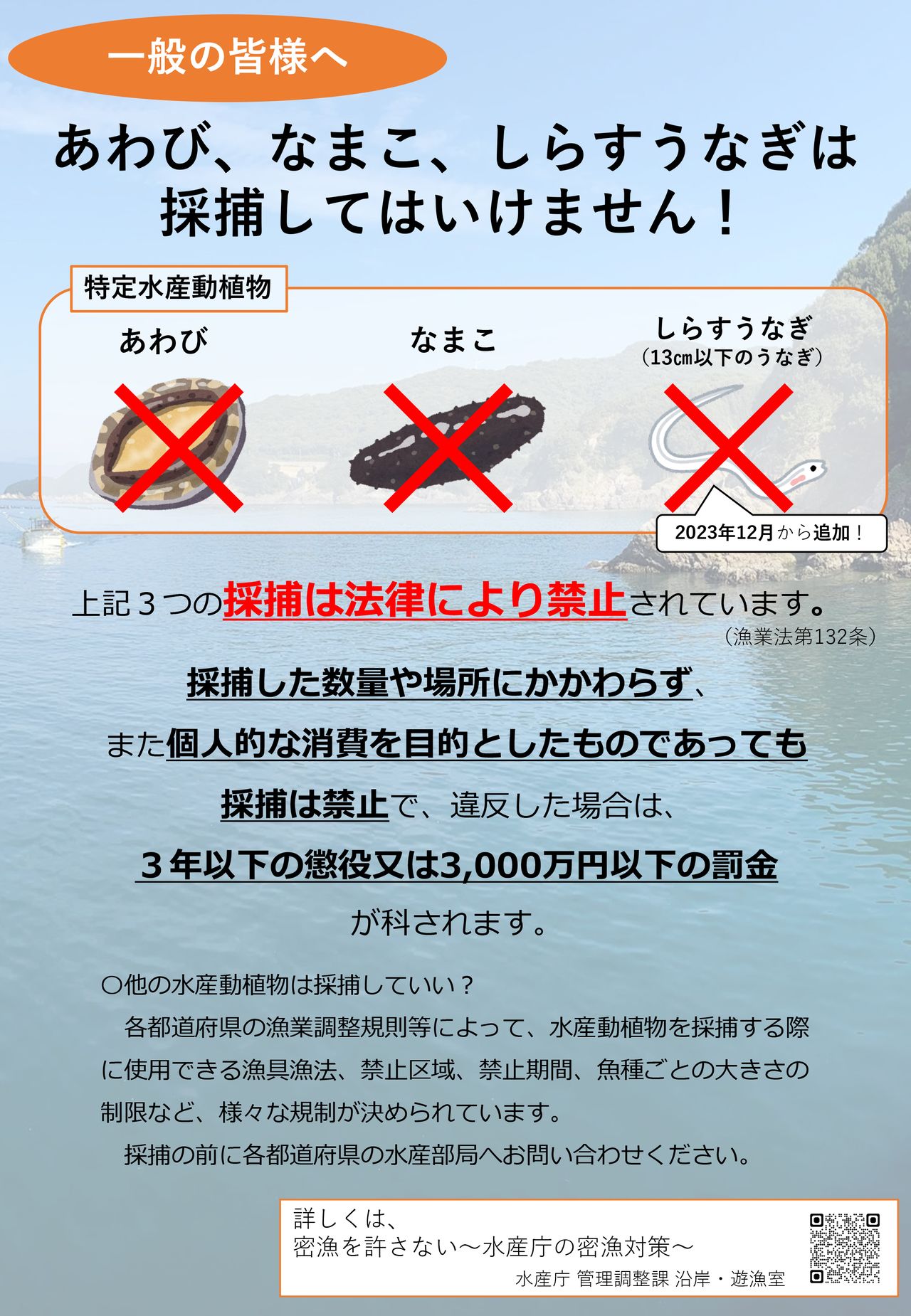

In the amended Fishery Act passed in December 2020, the government created provisions on the collection of specific maritime plants and animals, banning outright the collection of abalone and sea cucumbers. In December 2023, juvenile eels under 13 centimeters in length were added to this category. All collection of these creatures is illegal, irrespective of quantity, location, or whether the catch is intended for personal consumption, and violation is punishable by up to three years in prison or a fine of up to ¥30 million. The maximum fine for members of the public who collect turban shells or lobsters without a license was also increased, from ¥200,000 to ¥1 million.

This flyer explains that it is illegal to collect fish or shellfish without a commercial license. (Courtesy of the Fisheries Agency)

Social Media Abused

However, the stiffer penalties do not really appear to be working. Delicacies like abalone, sea cucumber, and turban shells (sazae) are transported via clandestine routes and form a valuable income stream for organized criminals. Poachers are therefore becoming more sophisticated. The Nagasaki prefectural government says that local poachers have become more organized, and have started using speedboats with modified engines and equipment allowing them to detect patrol vessels before they arrive. Recent years have seen an increase in the use of social media to recruit poachers and sell illegally gathered seafood online. People need to understand the law to make sure that what appears just to be a well-paid late-night job is not actually abetting criminal activity, and that their purchases of cheap shellfish may end up benefiting criminal gangs.

Poaching by foreign nationals is also on the rise, with illegal collection of blue crabs by Chinese and other foreign nationals rampant in both Tokyo and Ise Bays. In the coastal Hokuriku region, groups including Vietnamese nationals have been caught collecting shellfish delicacies. Despite the significant impact that poaching has had on natural resources in some regions, the difficulty in getting overseas nationals to observe the rules means that poaching is likely to become even more of a problem.

Sazae turban shells are a delicacy often targeted by poachers. (© Kawamoto Daigo)

Governments Take Action Against Recreational Poaching

The Fisheries Agency and local governments are also concerned about family and other groups who go to the beach for fun and ending up engaging in illegal collection of seafood, a practice described as “recreational poaching.” A Chiba fisheries operator angrily describes cases of groups have gone to the beach for a barbecue, and either collected abalone or turban shells to put on the barbecue, or used prohibited equipment to clear the area of every last turban shell or clam. The operator says that seaweed, including kelp and hijiki, is also being harvested illegally.

Shellfish collection is illegal at Chiba’s Kujūkuri beach. (© Pixta)

National and local governments are joining forces to educate the public on the rules by putting up signs and stepping up monitoring of the coastline. The Fisheries Agency says that different prefectures have different rules on illegal fishing, so members of the public should make themselves familiar with the rules for their area before going to the beach.

A look at the rules by municipality shows that most parts of Kanagawa Prefecture are covered by common fishery rights, under which the collection of abalone, turban shells, wakame, and kelp constitutes a violation. Here, while rakes up to 15 centimeters wide can be used to collect shellfish from designated tidal areas, the use of dredges and “ninja claw” rakes, which feature netting between the claws, is prohibited. In Aichi Prefecture, the tools that can be used by nonfisheries operators are specifically defined as fishing rods and specific types of nets, and fishing seasons and allowable sizes are specifically designated for the collection of abalone, striped mullet, juvenile eels, and other specific varieties.

“Ninja claw” rakes are readily available online, but their use is prohibited in many coastal areas. (© Pixta)

Members of the public forage for shellfish in Yokohama’s Marine Park. Several can be seen using illegal “ninja-claw” rakes. (© Kwamoto Daigo)

Bluefin Tuna Also Subject to Restrictions

The popular pastime of fishing is also subject to restrictions, with strict rules applying to the “diamonds of the sea”—bluefin tuna. Japan’s regional fisheries coordination committees have instructed that all bluefin tuna under 30 kilograms (even those caught accidentally while fishing for other species) must be released immediately. One bluefin tuna weighing 30 kilograms or more per person can be kept, but fishermen are still obliged to report their catch to the authorities, either using an app or other means. Starting in spring 2024, catches must be reported within three days. (Members of the public previously had up to five days to report their catch). Those who fail to comply will be ordered to do so by the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, with penalties levied if they ignore that order, according to the Fisheries Agency.

The number of fish that can be caught in a given period is also capped, and if there is a chance that the total catch will exceed the maximum, the season may be cut short. Indeed, the catching of large bluefin tuna was banned from April 6 to May 31, 2024. Violation is punishable by up to one year in prison and a fine of up to ¥500,000.

Ignorance of the law and casual offending are not excuses either. If you are going to the beach or going fishing, you should check local rules and information. And don’t even think about hauling in loads of bluefin tuna to make a quick buck!

A poster warning of restrictions on bluefin tuna fishing. (Courtesy of the Fisheries Agency)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A “no poaching” sign in Shakotan, Hokkaidō. © Kawamoto Daigo.)

Related Tags

fish environment resources marine strategies fishing poaching shellfish illegal