Center Ring: Exploring The Theatrical Side of Sumō

Sports- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Deciding Champions

Japan’s national sport of sumō boasts a long list of distinct traditions, from the distinguishing garb and hairstyles of wrestlers to the various rituals performed at tournaments. Among the numerous time-honored elements are some that bolster the show value of the sport.

One fairly recent invention is the championship system. Sumō in its earliest form was a simple battle of strength—it was reputedly much rougher than the sport today—and for most of history there was no formal structure for awarding titles or prizes to top-performing wrestlers. It was only in the end of the Meiji era (1868–1912) that an institutionalized system emerged whereby the wrestler with the best record at each tournament was crowned champion.

Takerufuji celebrates his victory at the spring tournament in Osaka on March 24, 2023, with his mother, Ishioka Momoko, at his side. He was the first sumō wrestler in 110 years to win the championship in his debut appearance in the upper makunouchi division. (© Jiji)

The first formal tournaments took place in the early Heian period (784–1183) and were held at the imperial court as part of a lavish celebration called sumai no sechie. The annual court event featured the best wrestlers from around the country, who competed as part of either the left or right garrison of the imperial guard.

Sumai no sechie eventually fell out of favor as the popularity of sumō ebbed and flowed over the centuries. The early decades of the Edo period (1603–1868) saw the rise of kanjin-zumō, public bouts held for the benefit of Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines. Wrestlers were grouped into two factions, east and west, with matches only taking place between wrestlers from opposite sides. Proceeds went toward construction and repairs of buildings. The events proved extremely popular, drawing large crowds of spectators.

Although sumō’s popularity was somewhat low in the early years of the Meiji era, 1909 saw the opening of the dedicated indoor arena Ryōgoku Kokugikan in Tokyo. It was during this period that the idea of crowning an overall champion at tournaments first emerged, helped along by the influence of the media and Western sports.

The Nihon Sumō Kyōkai, the managing association for the sport, initially instituted a group championship system that awarded a championship flag to either the east or west team based on the overall record of wrestlers in each faction. As there were no intrateam bouts during this period, fans were said to support their favorite wrestlers as well as their preferred side.

Around the same time, the newspaper Jiji Shinpō began awarding a prize to wrestlers who finished undefeated at tournaments. It also started the tradition of displaying large portraits of recent champions inside the arena. Such early attempts to establish a championship system had to contend with the age-old rules of sumō, which allowed for a range of ambiguous outcomes.

Along with a straightforward win or loss, a match could end in a draw, absence, or no-contest. (To add still more confusion to matters, if one wrestler failed to show up for a match, his opponent would also be marked as a no-show despite being there.) Each was recorded in its own column and did not count toward the final record of wrestlers.

Maegashira Takahanada (left), who would later take the name Takanohana and go on to become a yokozuna, and ōzeki Konishiki stand with their championship portraits at an unveiling ceremony in Tokyo in 1992. The presentation of portraits of the winners of the previous two competitions takes place the day before the start of each of the three tournaments held at the Kokugikan in Tokyo. (© Jiji)

Championship portraits hanging inside the Kokugikan. Commissioned by the Mainichi newspaper company, the images are of the winners of the last 32 tournaments. (© Jiji)

Controversy emerged in 1914 when the wrestler Ryōgoku claimed the top record in his debut appearance in the makunouchi division. Earning nine wins, he edged out yokozuna Tachiyama with eight wins to lead the east to victory. Some questioned the historic championship, as both undefeated wrestlers had sat out one bout, but Tachiyama, who also had one draw, saw his chance of earning a decisive ninth victory vanish when his opponent withdrew—some claimed for false reasons.

The Sumō Association officially adopted the individual championship system in 1926 following the establishment of the Emperor’s Cup the previous year, a prize still awarded to the top finisher of the makunouchi division. In line with this, the organization subsequently introduced new rules over a two-year span to guarantee that tournaments ended with one clear-cut winner. These included mandating rematches for draws and making uncontested bouts forfeitures.

Another significant change came in 1947 with the initiation of a playoff structure to decide championships in the case of tie records. The war years had taken a toll on the sport’s popularity, and the association felt that replacing the old custom of awarding the title to whichever wrestler was ranked higher would spice things up. These and other measures succeeded in adding to the excitement of sumō, setting the stage for its resurgence in the postwar period.

Prematch Spectacle: The Ring-Entering Ceremony

One of sumō’s grandest and most recognizable rituals is the dohyō-iri performed before the start of makunouchi division bouts. The first reliable account of it dates from the Kyōhō era (1716–36), but little other evidence remains as to the origins of the captivating show.

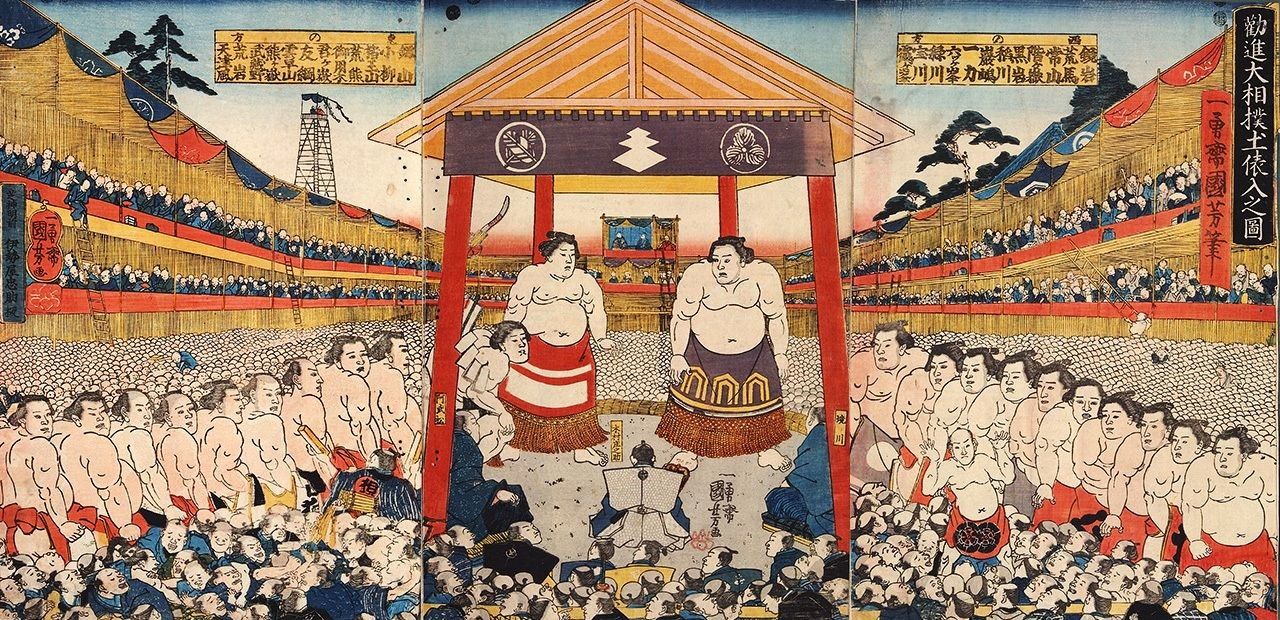

An 1849 print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798–1861) depicts the ring-entering ceremony. (Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library collection)

The dohyō-iri is all about projecting power to the audience through the facial features of the wrestlers and displays of ritual clapping and stomping. Kashiwade is a style of clap in which wrestlers bring both palms strongly together in honor of the Shintō deities. This is followed by shiko, a stomp that involves lifting each foot in turn high into the air and then firmly striking the ground in an expression of dominance over evil earthly spirits.

Prior to the Meiji era, wrestlers competing in the makunouchi division would perform kashiwade and shiko during the ring-entering ceremony in a similar manner as yokozuna do today, extending one hand out before stomping the ground to demonstrate their strength and balance. As the number of competitors in the division increased from the traditional 10, however, having so many burly wrestlers perform shiko while packed tightly around the ring became problematic, if not outright dangerous. Subsequently, shiko was done away with, and wrestlers now clap and raise both hands into the air before slightly lifting their decorative keshō mawash worn for the ceremony.

The custom of calling out the name of each wrestler as they make their appearance for the dohyo-iri is also relatively new. Traditionally, wrestlers entered and exited the ring during the ring-entering ceremony with little fanfare or regard to rank or stable. The current system, whereby wrestlers are led in order of rank into the arena by an umpire (gyōji) and step onto the dohyō as their name is called, was adopted in 1965 to make the ceremony more interesting for fans.

Wrestlers stand in a circle during the ring-entering ceremony. It is only performed prior to the start of matches in the jūryō and makunouchi divisions, the top two. (© Jiji)

The yokozuna dohyo-iri follows the makunouchi group ring-entering festivities. It was initially performed in 1789 by Tanikaze and Onogawa, the first two wrestlers to officially hold the rank of yokozuna. According to records, the wrestlers wore keshō mawashi and a special thick white rope called a shimenawa around their waists and were each led into the ring in turn by an attendant (tsuyuharai) bearing a large sword. It is unknown what form the ring-entering ceremonies took, but custom would dictate that the performance fit their rank of yokozuna and was conducted without undue pomp.

The yokozuna dohyo-iri grew in grandeur over the subsequent decades, with new elements added, including raising slowly from a crouch with one or both arms extend after performing a shiko stomp. Two distinct forms eventually emerged, the Shiranui style distinguished by both arms held opened and the Unryū style characterized by the left arm being bent and the right extended to the side.

Yokozuna Terunofuji performs the ring-entering ceremony in the Shiranui style. (© Kyōdō)

Fancy Pants

The mawashi, a wrestler’s sole attire in the ring and during practice, has its roots in a simple loincloth called a fundoshi. In the past, it was common for people to strip down to just the bare essentials when engaged in strenuous manual labor, and as a matter of course the fundoshi was adopted as sumō attire. Over time the garb evolved into the different types of mawashi worn today.

The type of mawashi donned by jūryō and makunouchi wrestlers for bouts is called shimekomi. These are made from silk satin woven in the Hakata-ori style. One of their distinguishing features is a stiff piece of fabric known as a sagari that tucks into the front and from which hangs numerous belt cords. Most sagari have 19 cords, but wrestlers can sport more or fewer, the only stipulation being that the total is odd—even numbers are considered inauspicious as they can be easily “broken.”

Takayasu slaps his shimekomi to prepare himself for a bout. (© Jiji)

Practice mawashi, on the other hand, are simple, cotton affairs. Those worn by wrestlers of the two highest-ranked jūryō and makunouchi divisions are white, while lower-ranked makushita wrestlers wear black mawashi for both practice and bouts.

Gōnoyama (left) pushes ōzeki Kotozakura during practice as lower-ranked wrestlers look on. (© Jiji)

All for Show

In contrast to the practice mawashi and shimekomi, the apron-like keshō mawashi worn during the ring-entering ceremony and special events is purely for aesthetics.

In the early part of the Edo period, white linen loincloths were the norm. However, as silk and satin come into use, wrestlers began adding picturesque patterns embroidered with gold and silver thread around the edges of their mawashi.

The decorative mawashi proved problematic the more ornate they became, with wrestlers’ fingers and hands often becoming entangled during bouts. By around the mid-eighteenth century, keshō mawashi and shimekomi had become distinct items, with the former being worn specifically for the ring-entering ceremony. The front part of the keshō mawashi steadily extended downward until it reached the top of wrestlers’ feet, the length it is today, providing more space for increasingly flamboyant designs.

Keshō mawashi are not cheap, typically starting at ¥800,000 and going up from there. Wrestlers usually do not front the costs, as the ornate items are generally gifted by patrons, fan clubs, or sponsors. The designs of keshō mawashi reflect the donor, such as featuring a company’s product, or have some significance to the wrestlers, like a nickname or item from their home prefecture or country.

From left: Takamizakari’s keshō mawashi plays on his “Robocop” nickname; Atamifuji’s displays a brand of custard pudding from his hometown; and Tobizaru’s features the Monkey King, a legendary character who, like the wrestler, is small but powerful. (© Jiji)

Two keshō mawashi stand out in particular for their opulence. The first was owned by Meiji-era yokozuna Hitachiyama and featured a laurel tree with leaves inlaid with pearls, rubies, and other jewels, and a 5-carat diamond as the centerpiece. This extravagance was only outdone by the keshō mawashi of Wakashimazu, which came with an eye-popping ¥150 million price tag and displayed a soaring eagle grasping a 10-carat diamond. (It is said that the mawashi itself was worth around ¥5 million, with the bulk of this value coming from the glittering gem.)

Although such sumptuous keshō mawashi are not seen today, the items remain one of the most eye-catching and expressive aspects of sumō.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Makunouchi wrestlers in keshō mawashi perform the ring-entering ceremony. © Jiji.)