Beyond Hachikō: Japan’s Many Tributes to Faithful Canines

Culture Guide to Japan History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Tragic Tale: The First Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition’s Dogs (Tachikawa, Tokyo)

The grounds of the National Institute of Polar Research’s Polar Science Museum in western Tokyo’s Tachikawa are home to a cluster of 15 statues of Sakhalin huskies. Together, they serve as a memorial to dogs left behind on the frozen continent after the first Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition of 1957–58.

This breed is also called Karafuto-ken in Japanese, taking its name from the former name used for the island Sakhalin, or Karafuto. They have long been kept as working dogs in Hokkaidō because of their hardiness. They can endure temperatures as low as minus 40 degrees Celsius, are obedient to humans, and are physically powerful. They can also go as long as two weeks without eating.

When officials decided to use Karafuto-ken as sled dogs for the Antarctic expedition, they selected 40 of the roughly 1,000 dogs in Hokkaidō for training, and the 20 top specimens were sent to Antarctica along with the expedition.

But then, in February 1958, when bad weather meant the second team replacement expedition was canceled and the first team had to be evacuated from Shōwa Base, the 15 surviving dogs were left chained in place.

The next January, 11 months later, another team returned to the base and were amazed to find that two of the dogs had broken off the chain and survived. Their names were Taro and Jiro, and their miraculous story inspired the 1983 film Nankyoku monogatari (Antarctica), later remade in 2006 as Eight Below, bringing them international fame in recent decades.

At left, statues of Taro and Jiro are on display in Nagoya port in front of the Antarctic exploration ship Fuji. At right is a photograph of Taro (left) and Jiro (right). (© Jiji)

The Japanese Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals erected a monument to the 15 dogs in September 1959 at the entrance to Tokyo Tower. The statues were later moved during maintenance of the tower grounds and in 2013 were donated to the NIPR, which installed them at their present location. With that, after nearly 50 years, the dogs were symbolically reunited with the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition.

The statues are varied, with some showing dogs seeming to howl sadly, while others cuddle up to sleep. Perhaps they are dreaming of their Hokkaidō homeland while awaiting the return of the expedition team.

The 15 bronze statues at the NIPR (left) were made by Andō Takeshi, the same artist who made the statue of Hachikō outside Shibuya Station (© Amano Hisaki). The picture at right shows the statues as they were outside the entrance to Tokyo Tower (© Jiji).

Bunkō, the Survivor Firedog (Otaru, Hokkaidō)

With its red brick warehouse district and quaint atmosphere, the western Hokkaidō city of Otaru retains the feel of its glory days of the early twentieth century. In front of one canalside brick building, known as the former Otaru Warehouse, stands a single bronze dog statue. This is Bunkō, and her statue has become a famous spot for tourists to visit in Otaru.

The statue of Bunkō stands near the entrance to the former Otaru Warehouse, built in 1893. (© Pixta)

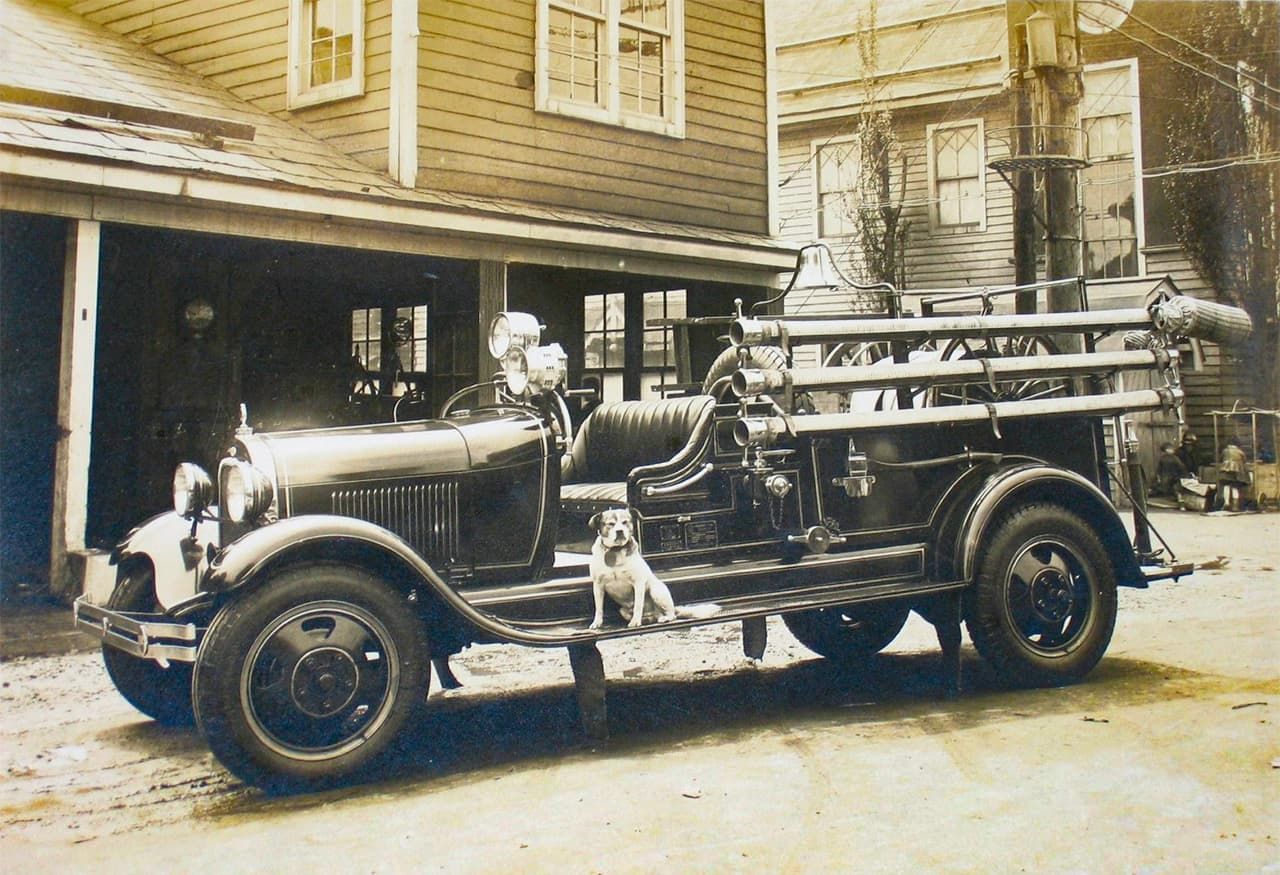

Bunkō was a mixed-breed dog kept by firefighters at the Otaru Fire Headquarters. The stories say that whenever they went out on a call, she would be the first on the truck and rode on the sideboard all the way to the fire. She went out on over 1,000 calls. Newspapers, magazines, and radio shows spread stories of her brave assistance as she kept onlookers back, carried the fire hose in her mouth, and more.

There were stories about how Bunkō learned to board the fire truck and get down on command. (Courtesy of the Otaru City Fire Headquarters)

She was rescued as a puppy when a fire fighter heard her whimpering in the remains of a burned-out building and took her back to raise at the fire house. She had a reputation as a very good dog, who loved wearing her uniform and even went off to visit the veterinarian on her own when she was sick.

She passed away on February 3, 1938, under the watchful gaze of many friends. She was 24 years old, which would be over 100 for a human.

Her bronze statue was installed in front of the warehouse in 2006. Ever since, the statue of fashion icon Bunkō has become a favorite of visitors for her various seasonal scarves, mufflers, and outfits.

There is another spot in Otaru where one can meet Bunkō, the Otaru Museum of History and Nature, next to the warehouse. The museum exhibits Bunkō's mounted remains. You can go see her yourself, with her white fur and brown spots, droopy ears, and mischievous grin.

Bunkō’s statue sports a scarf given by a resident. (© Yoshida Rieko)

At left, on the anniversary of Bunkō's death each year, residents offer up her favorite treat of caramels (© Yoshida Rieko). At right is the mounted body of Bunkō on display (courtesy of the Otaru Museum of History and Nature).

Dogs Standing In on the Pilgrimage to Ise Jingū, (Ise, Mie Prefecture)

The grand shrine of Ise Jingū stands at the top of all of Japan’s approximately 80,000 shrines. Among the shops lining the pilgrimage route to the outer shrines stands a venerable souvenir shop, Ise Sekiya Honten. A popular photo spot before the shop is a statue called Hishaku Dōji, of a child holding a ladle—hishaku—riding on the back of a dog.

The sculptor, Yabuuchi Satoshi, left an explanation on the sculpture’s pedestal.

“Long ago, many people longed to take a pilgrimage to Ise Grand Shrine, but those who could not make the trip on their own could have their desire fulfilled by dogs who went in their place. You could see dogs on the path to Ise Jingū, looked after by fellow travelers, with hishaku on their backs. The child in this statue signifies the dog’s kind heart.”

The Hishaku Dōji statue in front of Ise Sekiya Honten. (Courtesy of Ise Sekiya Honten)

With the completion of the Tōkaidō highway in the Edo period (1603–1868), the Ise pilgrimage became a major event that sparked faithful fervor in the common people, and once every 60 years a mass pilgrimage filled the road. It was called okagemairi, a pilgrimage to receive the favor—okage—of the divinities.

Some who could not make the journey due to illness or other reasons sent okageinu—pilgrimage dogs—in their place. These dogs traveled to Ise Jingū with hishaku strapped to their backs.

The first documented mention of these dogs dates to 1771. The head priest of the shrine wrote that a dog had come to receive a blessing in place of its owner, Takada Zen’emon of the province of Yamashiro (present day Kyoto).

The dogs wore tags indicating the name and home of their owners and explaining that they were on the pilgrimage to the shrine, as well as strings of money around their necks.

Naturally, the dogs could not find the shrine on their own, never having seen it before. There was, in fact, a support system in place, known as “village sendoff,” where people along the road would guide the dogs from village to village. At the time, people believed that offering the dogs a warm welcome would earn them a blessing as well, so it seems there were very few who stole money from the dogs.

An ukiyo-e by Utagawa Hiroshige, Yokkaichi, Hinagamura oiwake, sangūdō (Yokkaichi: The Junction of the Road to Ise Shrine at Hinaga), includes an okageinu in front of the torii. (Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art New York City, United States)

However, in the 1870s, restrictions on dog ownership spread across Japan, and pet owners became much more careful about managing their dogs, changing the situation. The okageinu began to disappear from the roads.

But now, 150 years later, they are once more becoming a hot topic. At Okage Yokochō, a shop district lying before Ise Grand Shrine’s gate, owners can bring their dogs for a bit of okageinu cosplay. Visitors can adorn their dogs with sacred shimenawa ropes and cloths for a walk around the area. As a bonus, they also receive an omamori charm against illness.

At left, a modern day okageinu out for a walk through Okage Yokochō; at right, the hugely popular Okageinu Phone Strap souvenir. (Courtesy of Okage Yokochō)

Chirori, Japan’s First Therapy Dog (Chūō, Tokyo)

Just a five-minute walk from the Ginza Station on the Tokyo Metro through the bustling streets of Ginza can take you to the quiet Tsukiji River Ginza Park, near the Kabukiza theater. There, you can see a statue of a mother and her pups. This is a memorial to Chirori, a rescue dog who went on to become Japan’s first therapy dog.

A monument to Chirori and her pups at the entrance to the park, near the nursing home where she served as a therapy dog. (© Amano Hisaki)

Therapy dogs help soothe and support elderly and other patients undergoing medical treatment or nursing care. There are numerous reports of their effects in contributing to emotional stability and improving dementia, as well as helping stroke recovery.

In the summer of 1992, Chirori was slated for euthanasia at a shelter when she was rescued by Ōki Tōru, a musician and founder of the International Therapy Dog Association. Despite starting out as an abandoned crossbreed with a lame right leg, she helped care for the elderly and the weak for well over a decade, until her death in the spring of 2006.

Her great charm was in her adorable eyes. She would make affectionate eye contact with her partner, soothing the troubled hearts of patients.

The stories are beyond counting. People threw themselves into rehabilitation out of pure desire to reach out and pet Chirori; others saw their paralyzed hands began to move again; and there were some who regained the ability to speak, or even the will to live.

Chirori’s greatest gift, though, was in paving the way for other abandoned pets to become therapy dogs, says Ōki.

“When I visited hospitals after the Great East Japan Earthquake, everyone already knew about therapy dogs and welcomed me. Those who had lost their own dogs in the tsunami would grip pictures of their pets while they hugged the therapy dogs tight.”

Hasegawa Satokichi, at right, nuzzling Chirori. After Chirori’s comfort helped him through rehabilitation, he recovered from needing intensive nursing care to being able to stand on his own. Ōki Tōru is at left. (Courtesy of the International Therapy Dog Association)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Fifteen bronze statues at the National Institute of Polar Research Polar Science Museum. They were made by Shibuya Station’s Hachikō statue artist Andō Satoshi in memory of the Karafuto-ken who died when the first Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition had to evacuate and leave them behind. © Amano Hisaki.)