Shibusawa Eiichi (1840–1931): Scion Shibusawa Masahide Reminisces

Economy Society History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Looking Back at a Storied Ancestor

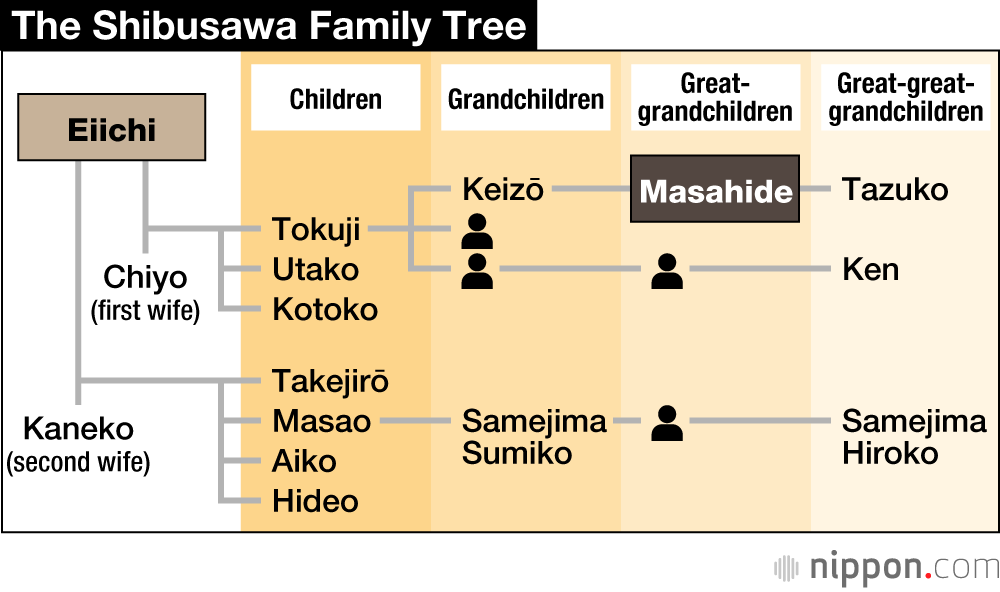

Shibusawa Masahide was born in 1925 to Keizō, grandson of the famed Japanese entrepreneur Shibusawa Eiichi (1840–1931), in London, where Keizō was employed by the Yokohama Specie Bank, predecessor of the Bank of Tokyo and now part of MUFG Bank.

Masahide on his great-grandfather Eiichi’s lap. (© Shibusawa Memorial Museum)

In a sepia-toned photograph, Eiichi dandles Masahide on his knee. “I believe this photo was taken in the fall of 1925. I was born in February, so I was around six months old. My family had returned from London that month, and I think the photo was taken because Eiichi wanted to hold me.”

Only three personages have ever been depicted on Japan’s ¥10,000 banknote. The first two were Prince Shōtoku (574–622), an Asuka period (593–710) statesman, and the educator Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835–1901). Shibusawa Eiichi, featured on the new bank note to be issued in July 2024, joins them now.

“How do I feel about that?” quips the great-grandson. “Nothing in particular. I do think it was a good choice, though, and it’s an honor for our family.”

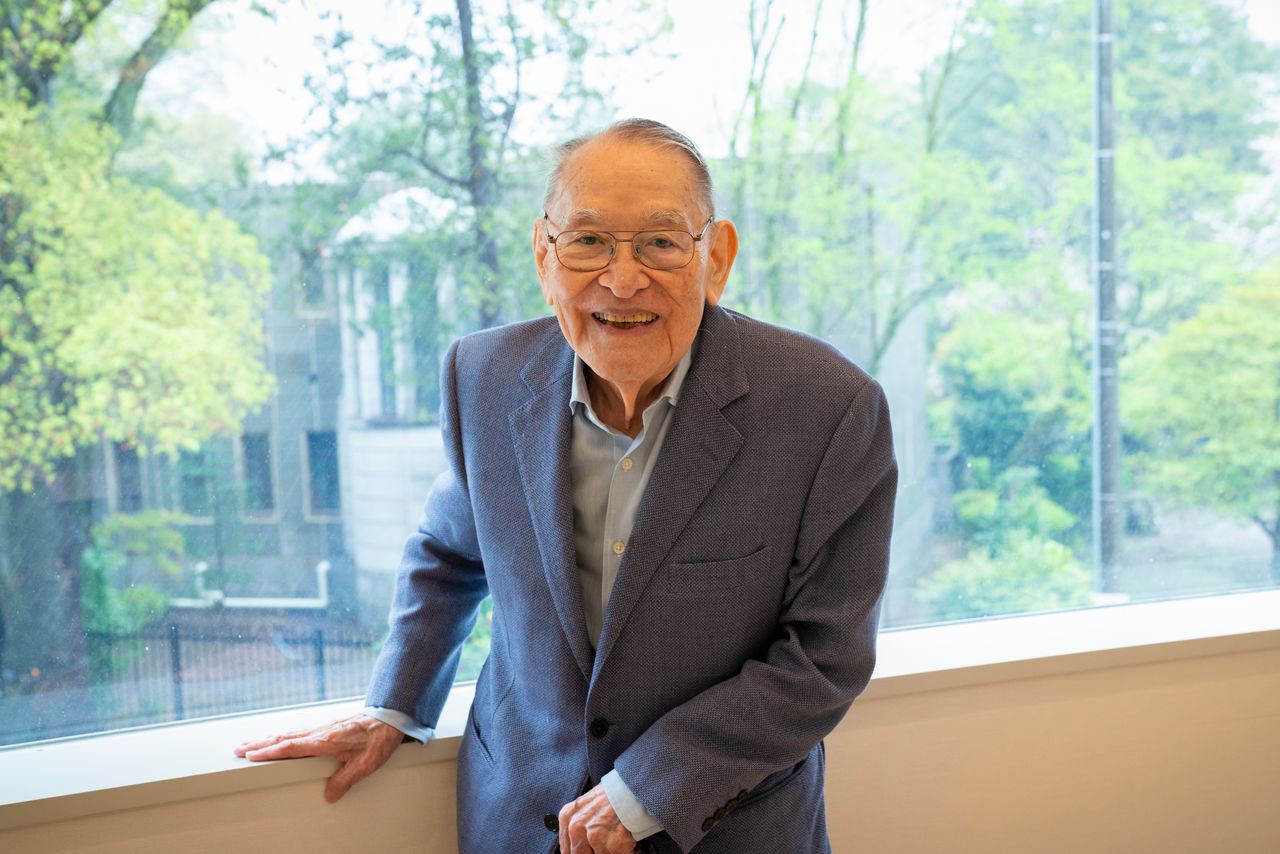

Aged 99, Masahide has outstripped Eiichi in longevity, who himself lived a long life. (© Ōsawa Hisayoshi)

The family remains home to the spirit of entrepreneurship that drove its members’ celebrated ancestor. Among Eiichi’s great-great-grandchildren are Shibusawa Tazuko, executive officer of the Shibusawa Memorial Museum; Shibusawa Ken, founder and chairman of Commons Asset Management; and Samejima Hiroko, founder and principal of the Andu Amet brand, which produces fair-trade luxury handbags in Ethiopia.

Eiichi died at the age of 91, when Masahide was six years old. The great businessman’s many activities kept him fully occupied and left him little time for family life. As his great-grandson recalls: “At the age of four or five, my only impression of Eiichi was that he was an important man. I recall that his funeral was quite a grand affair.”

Ultranationalist Beginnings

Born in 1840 to a prosperous farming family in what is today Fukaya, Saitama Prefecture, Eiichi was caught up in ultranationalist fervor and plotted in 1863 to attack and burn the foreign settlement in Yokohama. The plot fell through, and fearing arrest, Eiichi escaped to Kyoto, where he entered the service of the household of Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the last Tokugawa shōgun.

“It was a good thing that Eiichi wasn’t able to carry out the attack,” says Masahide. “Otherwise, he would have been killed.”

In 1867, Eiichi traveled to France as a member of a delegation representing Japan at an international exposition in Paris, an experience that exposed him to the progress evident in modern Western countries and led him to renounce his nationalist views. He espoused the drive to modernization promoted by the new Meiji government, which he joined as a finance ministry official. Resigning his post a few years later to become an entrepreneur, Eiichi ultimately founded and operated over 500 banks, companies, and organizations, many of which are still in operation today (often in different forms), as seen in the first list at the bottom of the article.

The new ¥10,000 note depicting Shibusawa Eiichi. (© Jiji)

Not a Zaibatsu

But Eiichi’s great-grandson Masahide, who has produced several scholarly works about his ancestor, asserts that his activities went far beyond those of a businessman.

“Rather than being an out-and-out entrepreneur, Eiichi was more a person of culture, or if you will, someone who thought of what would be best for his country. I don’t think he ever touched a project that was sensitive or risky. On the other hand, if he believed he could provide something of value, he didn’t hesitate to put himself forward, whether it be for the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce, the Imperial Hotel, or other projects. If someone came to him with an idea, he would marshal his connections and round up a team to work on it. He was very public-spirited.”

Eiichi’s contemporary Iwasaki Yatarō, head of the Mitsubishi business conglomerate, espoused a completely different business philosophy. In a speech given before the Saitama Employers’ Association in 2010, Masahide related the following episode. Iwasaki Yatarō invited Eiichi to cruise on a pleasure boat, where he proposed that the two should monopolize operations in order to take control all of Japan’s business between them. Eiichi refused to cooperate, citing his belief in gappon shugi—the philosophy of ethics and integrity in business based on Confucian teachings. To the fabulously wealthy Iwasaki, thoroughly imbued in the American-style way of doing business, Eiichi, who believed in everyone pooling their monetary resources to modernize Japan’s economy, must have seemed quite naïve in his approach.

As we have seen, Eiichi had a hand in setting up many of what are today’s Japan’s most illustrious enterprises. But in most cases, he was not at the helm for very long. “Eiichi was always very receptive to ideas for bringing Japan up to par with the West and ready to join in,” notes his great-grandson. “However, rather than being directly involved in managing, he was more of a supporter.”

For a man of his age, Masahide has astonishing recall and gives clear, concise answers. I commented that some people refer to Shibusawa as having established a zaibatsu, a conglomerate like the Mitsubishi concern, an assertion he emphatically rejects.

“Nothing could be farther from the truth! It was like this: If Eiichi’s worth at the time was ten million yen, the wealth of conglomerates like Mitsubishi or Mitsui was something like 300 or 500 million yen, money that gave them immense power. Certainly, Eiichi wanted money so that he could wield influence, but I don’t think he wanted to grow his wealth simply for personal aggrandizement.”

Masahide was interviewed at the Shibusawa Eiichi Memorial Foundation’s Seien Bunko, an important cultural artifact built by the Shimizu-gumi (today Shimizu Corporation) the year he was born. (© Ōsawa Hisayoshi)

Working for the Public Benefit

Masahide emphasized Eiichi’s role as a philanthropist who was involved in over 600 social enterprises. The present forms of some of them are in the second list below.

According to Masahide: “Eichi personally headed the Tokyo Yōikuin orphanage [later the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Geriatrics and Gerontology], Japan Women’s University, and the Tokyo Jogakkan girls’ schools. While he jointly managed most of the commercial enterprises he founded, I suppose that in the case of schools, he felt that he should be directly involved. I believe that he manifested his intentions most clearly through his culture-related undertakings.

“Rather than economic issues per se, even from his early years Eiichi cared most deeply about the kind of country Japan should become. In general, people prioritize work, but Eiichi seems to have struck a good balance between work and his drive to help build the modern Japanese nation.”

Masahide smiles as he looks at family photos. (© Ōsawa Hisayoshi)

Honoring the Shōgun Yoshinobu

Although rarely mentioned as one of Eiichi’s great accomplishments, Masahide touched on his great grandfather’s work on a biography of Yoshinobu, the last shōgun of the Tokugawa line. Eiichi never forgot how Yoshinobu had protected him after his abortive plot to destroy the foreign settlement at Yokohama, nor his invitation to travel to Europe as part of an official Japanese delegation. Whenever the opportunity presented itself, Eiichi would travel to visit Yoshinobu in Shizuoka, where he was living quietly in retirement.

Eiichi put the biography compilation in motion, enlisting many notable figures, including Fukuchi Gen’ichirō, head of the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun (today the Mainichi Shimbun), to work on the project. After more than 20 years of labor, an eight-volume biography of Yoshinobu was produced, which appeared four years after the former shōgun’s death. Eiichi most likely wanted to set the record straight about the role that Yoshinobu had played as the Tokugawa years drew to a close and the new Meiji government was born.

“Eiichi felt that Yoshinobu’s accomplishments had not been fairly portrayed, and the biography was his attempt to rectify this. I believe that the two were very close. I suppose that few people gave much thought to Yoshinobu once the Meiji era (1868–1912) began, but Eiichi certainly did. That biography is a valuable document about one period of Japan’s [modern] history.”

At the end of our interview, I asked Masahide once more about the choice of Eiichi for one of the new banknotes.

“I think it’s a good choice, because nowadays there are few people like him.”

There is a saying that finance is the lifeblood of the economy. Eiichi’s long life covered turbulent times in Japanese history, from the waning years of the Edo period (1603–1868) through to the 1930s. As the face of the new ¥10,000 note, he will become part of today’s economic lifeblood. Today, when global capitalism has spread disparity and division, that banknote will serve to remind us of Eiichi’s stance of ethics and integrity in business.

Shibusawa Masahide with the bust of his great-grandfather on which the banknote likeness was modeled. (© Ōsawa Hisayoshi)

Principal Commercial Enterprises Founded by Shibusawa Eiichi

- Mizuho Bank

- Resona Bank

- Ōji Holdings

- Tokyo Gas

- IHI

- Isuzu Motors

- Tokio Marine and Nichidō Fire Insurance Co.

- Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings

- Tōyōbō

- Taiheiyō Cement

- Mitsukoshi

- Tokyo Metro

- Kirin Holdings

- Shimizu Corporation

- Tokyo Rope Manufacturing

- Imperial Hotel

- Sapporo Holdings

- Asahi Group Holdings

- Taisei Corporation

- Furukawa Electric

- Fujitsu

- Yokohama Rubber

- Tōyō Keizai

- Kawasaki Heavy Industries

- Tōhō

- Imperial Theater

- Tokyo Kaikan

- Tokyo Bankers’ Association

- Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Tokyo Stock Exchange

Main Social Enterprises in Which Shibusawa Eiichi Played a Role

- Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Geriatrics and Gerontology

- Japanese Red Cross Society

- Tokyo Jikei University School of Medicine

- Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japan Foundation for Cancer Research

- Hitotsubashi University

- Kōgakuin University

- Tokyo Keizai University

- Tokyo Jogakkan Schools for Women

- Japan Women’s University

- Takushoku University

- Urban redevelopment of Den’en Chōfu (Ōta, Tokyo)

- The Japan-India Association

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Shibusawa Masahide, at the Shibusawa Memorial Museum in Tokyo’s Asukayama, where Eiichi spent the last years of his life. © Ōsawa Hisayoshi.)