Ahead of the Times: Flag-Waving Communication and Japan’s Dōjima Rice Exchange

Economy History Travel Guide to Japan- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Pioneering Futures Market

Japan’s monumental economic legacy includes one of the world’s first organized futures markets, the Dōjima Rice Exchange. Standing on the northern bank of the Dōjima River in Osaka, it was initially dominated by different groups of merchants. In 1730, the Tokugawa government, seeing it as an instrument for adjusting the price rice, authorized it as a place where merchants could trade in rice certificates and speculate on securities, much as modern traders do today.

A stone monument in the shape of a grain of rice marks the location of the Dōjima Rice Exchange. (© Abe Haruki)

Despite the market’s forerunner status, its historical importance has largely faded from public consciousness. Visiting the site, now dominated by the towering Hanshin Expressway, a rice-shaped stone monument and a placard emblazoned with a print by famous ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Hiroshige are all that mark where the market once stood.

Dōjima’s legacy has not been completely forgotten, however. For instance, tours of the Chicago Board of Trade, a pioneering futures exchanges first opened in 1848, cite the Japanese market’s legacy. Dōjima’s importance in modern derivative trading has also been the subject of scholarly studies by modern economists.

One aspect of the rice market that has been overlooked, however, is how prices and other information from Dōjima were quickly and reliably relayed, sometimes across great distances. Below I will look at the system of flag-waving communication (hatafuri tsūshin) that emerged to meet this vital need.

Time is Money

The fortunes of rice brokers hinged on their ability to stay abreast of the latest market conditions. Early on, dedicated couriers called kome bikyaku conveyed information to and from merchants in different economic centers. Although speedier than other types of courier services, they still took many hours to relay information from Dōjima to neighboring rice exchanges in places like Nara and Kyoto. Telescopes had been introduced in Japan in the 1600s, and flag-waving communication arose from the demand for even quicker transmission of information by utilizing the technology to rapidly send market prices and other news over long distances.

Few details are known about flag-waving communication during the Edo period (1603–1868). However, a historical survey carried out by the Osaka municipal government published in 1932 credits a rice broker from the village of Wakai in present-day Nara Prefecture with the first attempts of transmitting market information by optical means. According to the work, Ōsaka no hatafuri tsūshin (Osaka Flag-Communication) by economist Kondō Bunji, sometime around 1745 a rice broker named Gensuke arranged for signals to be sent from Honjō, a wooded area approximately two kilometers from the Dōjima market. Early attempts utilized such items as smoke, large umbrellas, lanterns, and hand towels, with flags eventually becoming the preferred mode of communication. These signals were verified at Jūsan Pass in the mountains east of Osaka with the aid of a telescope.

An information placard at the site of the Dōjima Rice Market. (© Abe Haruki)

It did not take long for the method to catch on. Brokers developed new techniques and set up their own dedicated transmission routes, adding relay points to extend range and in other ways improving the quality and speed of information being sent.

In 1775, the Tokugawa government clamped down on flag-waving communication and other methods of transmitting market prices. The reasoning behind the move is unclear, but some experts speculate that it was prompted by objections from leading rice couriers, whose services were the officially recognized means for communicating market information, suggesting flag-waving was quickly gaining dominance. For whatever reason, it attracted the attention of the shogunate, who deemed it problematic and ordered brokers to stick to established procedures for sharing market information.

The prohibition order initially covered only nearby of Settsu, Kawachi, and Harima, and brokers wasted no time in exploiting this loophole by having couriers ferry information outside of restricted areas, then switching to flag-waving signalers. There were others who ignored the rules outright and continued to carry out flag-waving communication clandestinely. The government time and again issued new ban orders, but seemingly to little effect as evidence suggests that signaling networks continued to connect Dōjima with rice markets in Kyoto, Ōtsu, Nara, Wakayama, and Hyōgo.

Jet-Like Speed

The government maintained its ban until 1865. By then, Japan had signed a number of treaties with Western powers who were pressuring the country to open further. In September of that year, a flag-waving signaler either in Amagasaki or on Mount Rokkō—it is unclear which—spotted a flotilla of British, Dutch, and French military vessels in the waters off Kobe and relayed his discovery to the regional shogunal representative. Citing the incident, the head of the rice exchange in Kyoto petitioned the government to lift its ban on flag-waving communication, which it did, opening the way for its broad use at Dōjima and elsewhere.

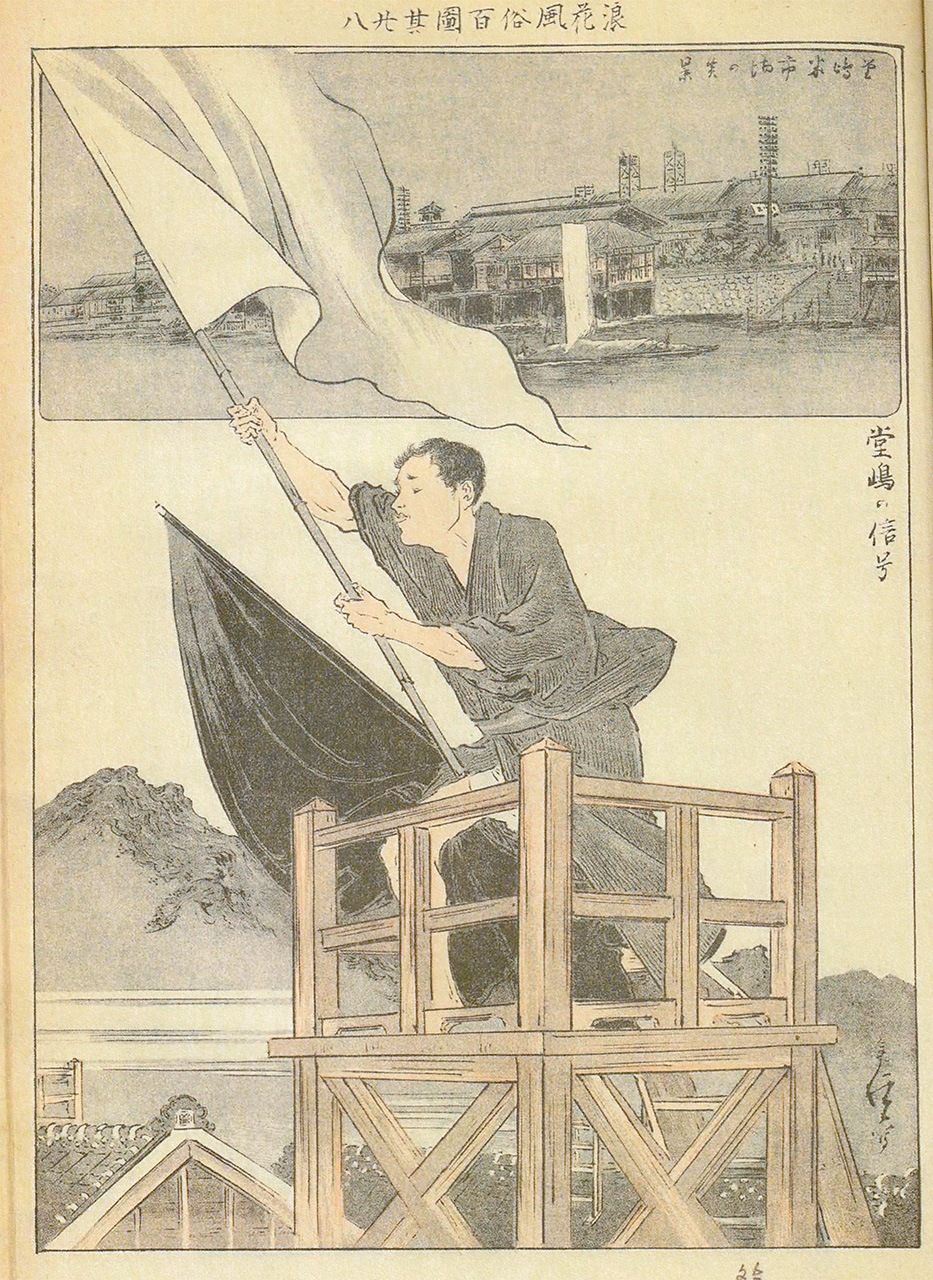

A signaler waves a flag from a platform atop the Dōjima Rice Exchange in a print from the series Naniwa fūzoku hyakuzu zukai (One Hundred Views of Naniwa). (Courtesy National Diet Library)

The network rapidly expanded westward to Okayama, Hiroshima, and Hakata and eastward to Kyoto, Nagoya, Shizuoka, and the capital of Edo (now Tokyo). Shibata Akihiko, a leading expert on flag-waving communication, retraced many of these routes and found that the distance between relay points ranged from 4 to 22 kilometers. These points were typically set in the mountains or at passes, many of which still bear names like Hatayama (flag mountain) indicating their importance in flag-waving communication.

Shibata, based on reenactments of flag waving, found that a message sent from Dōjima would reach Wakayama in 3 minutes, Kyoto in 4 minutes, Kobe in 7 minutes, Kuwana in northern Mie Prefecture in 10 minutes, Okayama in 15 minutes, and Hiroshima in just under 40 minutes. The rate amounts to an average speed of 12 kilometers a minute or a blistering 720 miles an hour—roughly the same speed as a passenger jet.

Messages to the capital of Edo took a considerably longer eight hours due to Mount Hakone standing in the way, an obstacle requiring information to be relayed on foot between Mishima and Odawara. However, this was still a significant improvement from the three to five days that courier services took to traverse the route.

Flags and Signs

The system for conveying information was sophisticated and utilized an array of flags of different sizes and colors. Although there are no records showing the techniques of flag signalers from the Edo period, it can be assumed to be very similar to that from the Meiji era (1868–1912) described in Kondō’s work.

Signalers used flags of smooth, plain-woven muslin, waving large ones (91 cm x 167 cm or 97 cm x 152 cm) on cloudy days and smaller ones (61 cm x 106 cm) in fine weather. Black flags were utilized at relay points in the mountains, where there was a relatively clear line of sight, and white flags in low-lying areas dominated by foliage and other obstructions.

Signalers initiated messages by swinging a flag straight down the center. To transmit number amounts, the flag was swung to the right to express tens and to the left to indicate ones. For instance, “24” would be expressed with two swings to the right and four to the left. The receiver at the next relay point would confirm the transmission by repeating it. If there was a mistake, the sender would swing his flag straight up and down and then left to right to indicate an error.

Signalers often used a type of shorthand consisting of corresponding numbers (aiin) decided and shared ahead of time that corresponded to certain figures (“5” could be assigned to verify “14”). To limit the risk of information being stolen, codes and keys were devised, such as adding or subtracting amounts to change numerical values, not unlike modern encryption methods. However, such added safeguards came at extra cost to senders.

The characters of the Japanese phonetic alphabet were also given numerical values, enabling worded messages to be sent.

A Distinct System

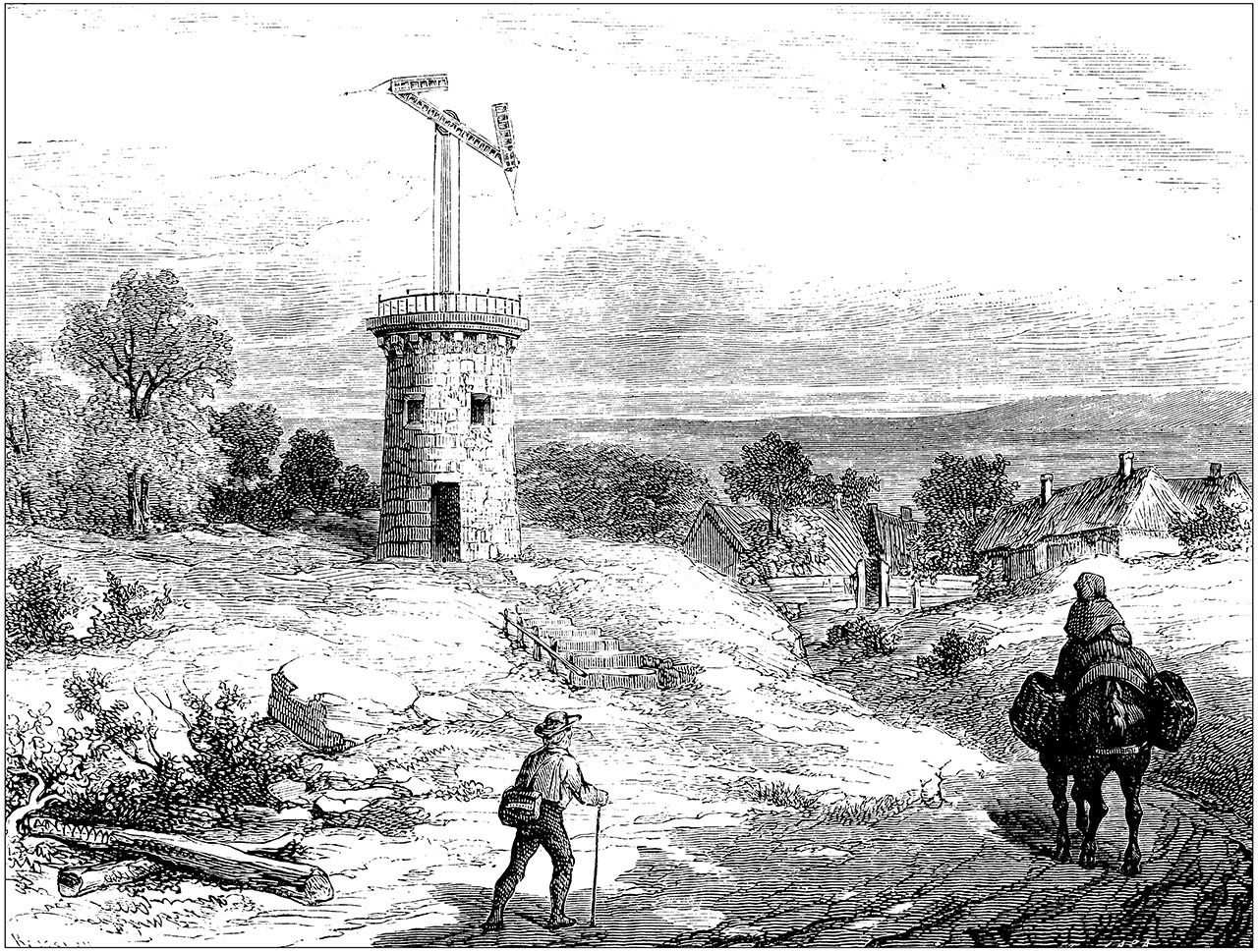

There are examples of optical signaling in the vein of Japan’s flag-waving communication from other countries as well. One of the best known is the Chappe telegraph by French inventor Claude Chappe. First demonstrated in 1793, it consisted of lines of relay towers equipped with a wooden mast supporting a movable crossbeam and two pivoting arms that could be positioned to indicate numbers and letters.

The government started using the telegraphs for military purposes during the French Revolution, and Napoleon extended the network within France to some 600 kilometers. With the system, a message sent between Paris and Brest, a distance of 551 kilometers, reached its destination in eight minutes. The technology spread across Europe, extending 14,000 kilometers at its peak.

A Chappe telegraph. (© Getty Images)

In Japan, Chappe’s telegraph garnered attention but was not adopted as the native flag-waving system was already established. Comparing the two modes, the proliferation of Chappe’s telegraph was driven by military need, whereas Japan’s flag-waving communication, save the incident off the coast of Kobe, was purely an economic endeavor.

The demand for speedy information sustained flag-waving communication into the early twentieth century, even as means such as the telegraph and telephone took hold. However, it eventually disappeared, bringing to close a chapter stretching back some 300 years.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: An illustration of flag-waving signalers from Fūzoku kidanzu Ōtsu Oiwake sono ni sōba hatafuri narabi ni kanrin junra no zu [Account of Flag-Waving Market-Price Signalers at Oiwake in Ōtsu]. Courtesy National Diet Library.)