The Prescience and Universality of Tezuka’s Manga Masterpiece “Black Jack”

Manga Anime Health Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Monumental Work of Medical Manga

Don’t you think it’s presumptuous that humans can determine the lives and deaths of other living things?

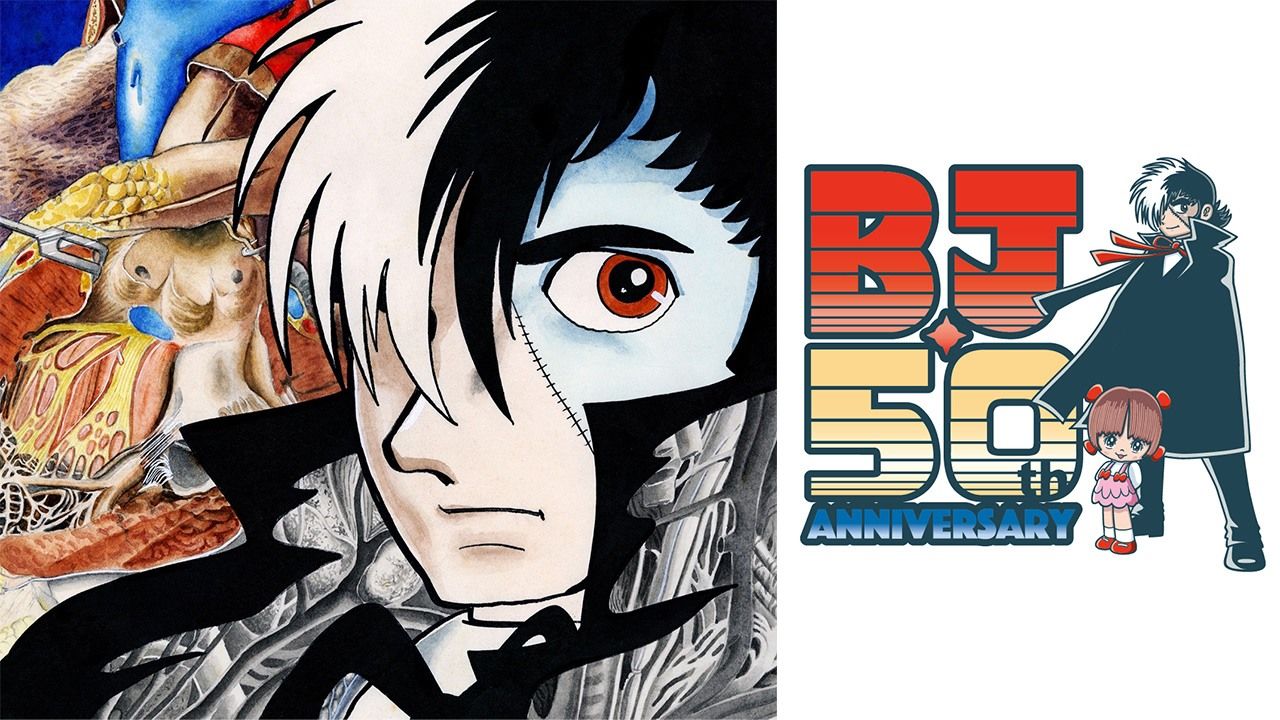

This is one of the most famous lines from Black Jack. November 2023 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the debut of Tezuka Osamu’s medical-themed masterpiece.

Black Jack began serialization in 1973. This was the year of George Lucas’ American Graffiti, and the year the United States began its withdrawal from Vietnam. It was the peak of Japan’s second postwar baby boom, marking the beginning of a birthrate decline that continues today. It was an era the historian Eric Hobsbawm described this as “the turning point from the golden age to the crisis decades.” Such was the world in which Black Jack arrived.

The first installment appeared in a manga magazine called Shōnen Champion. It was a hothouse for creativity, featuring classics such as Mizushima Shinji’s baseball series Dokaben and Yamagami Tatsuhiko’s Gaki deka (Kid Cop), and continues to produce hits today, such as Grappler Baki (Itagaki Keisuke) and Yowamushi Pedal (Wataru Watanabe).

The series is named for its protagonist, a Japanese doctor named Hazama Kuroo, who calls himself Black Jack. He is a genius with a scalpel, capable of saving patients with miraculous feats of surgery. But he possesses no medical license, and charges exorbitant fees for his services. Dark rumors abound that he conducts human experiments, and he is ignored by the mainstream medical community.

As it turns out the rumors are true. But he also possesses a fierce desire to save lives, making him a complicated man full of contradictions.

A famed scene from the manga in which the spirit of Doctor Honma speaks to Black Jack, delivering the line at the top of this article, after the loss of a surgery patient. (© Tezuka Productions)

Black Jack is the creation of Tezuka Osamu, a pioneer of incorporating cinematic techniques into what came to be called “story-driven manga.” Revered for creating classics including Astro Boy, Adorufu ni tsugu (trans. Adolph), and Hi no tori (Phoenix), he is widely known as the “God of Manga” today.

Born in 1928 in the city of Toyonaka, Osaka, he grew up during the war. As a child he immersed himself in films and stage plays. He also had an affinity for astronomy and loved collecting insects.

Eventually he entered a junior high school famed for its strict rules. But Japan was at war, and Tezuka, with his weak physique, was sent to a “health and discipline academy,” designed to prepare “unfit” youth for military service. In his autobiography Boku wa mangaka (I Am a Manga Artist), he wrote of suffering brutal hazing there.

The experience formed the basis for the deep aversion to war and totalitarianism seen in his oeuvre. Black Jack is grievously injured in an explosion as a child, caused by an unexploded munition from a former military facility.

Due to the military’s carelessness, his mother loses her limbs and ability to speak, and his father runs off with his mistress. Black Jack’s injuries are so severe that the medical establishment gives up on him altogether, save for one Honma Jōtarō. Dr. Honma’s dedication inspires Black Jack to pursue medicine as a career.

In the academy, Tezuka suffered an arm injury serious enough that he developed sepsis, raising the specter that it might have to be amputated. But the doctor who successfully treated him opened his eyes to the nobility of the profession, and he resolved to become a doctor himself.

In 1945, he enrolled in the Medical Department of Osaka Imperial University. He made his professional manga debut at this time, juggling his studies all the while. After a medical internship, he obtained a medical license and eventually completed his research on the sperm of pond snails that earned him his doctorate in medicine.

As a physician, Tezuka had a tendency to envision his patients’ faces as if they were manga characters, penning caricatures of their features, and jotting down story ideas in the midst of examinations. It was during this time that Tezuka developed his concept of an idealized doctor, which he later used as the basis for Black Jack.

Born in Osaka Prefecture in 1928, Tezuka Osamu made his professional manga debut in 1946 and continued producing work at a prodigious rate until his passing at the age of 60 in 1989. (© Tezuka Productions)

A Manga Master Wrestles With a Human Dilemma

Every episode of Black Jack tells a self-contained story. In one, Black Jack is paid a huge sum to treat the war injuries of a wealthy family’s son. In another, he saves the life of an elderly man who finds his life’s purpose in caring for a zelkova tree. In one particularly bold episode he buys an entire hospital to perform surgery on a benefactor. The series explores rare conditions and diseases, such as a mysterious condition such as one where a patient’s body begins sprouting tree-like buds.

Some of the conditions defy scientific explanation. One involves a growth resembling a human face; another, a strangely shaped tumor that hinders removal using supernatural powers. In that episode, Black Jack successfully removes the “tumor,” which turns out to be a parasitic twin, and nurses it into independent life as his assistant, Pinoko.

Sometimes, Black Jack even plays the supporting role. An episode titled “Memories of an Old Woman” stars a protagonist who is a struggling nurse. She quits her job to become a wet nurse for a certain child. The child later undergoes a surprising transformation, becoming no less than the president of the United States, making this episode perfectly capture the theme of the series: “in saving a person, you may change history.”

Tezuka shies away from realism, focusing more intently on the stories of the characters. This is designed to heighten the depiction of human wants and desires. This is deliberate; if realism were the point, then more photorealistic drawings would be a better choice. Unbound by the shackles of realism, Tezuka’s imagination can soar.

These days, this kind of stylistic approach is much more appreciated. But back in Tezuka’s time, society at large still had a strong bias against manga. The painstaking detail with which Tezuka portrayed his scenes led to criticism about the reality of his stories. Indeed, the medical techniques he portrayed were already outdated even by his era.

But Tezuka insisted that his aim was not to portray medical techniques with scientific accuracy. He stylized them to accentuate his theme. And that theme, in a nutshell, was the dilemma of being human.

For instance, as Tezuka writes in the novel Garasu no chikyū o sukue (Save Our Mother Earth): “When Black Jack cures a patient, he is also extending their life. And in fact this is true of medicine as a whole. So as a result, fewer will die, and the numbers of elderly will continue to increase, leading to a very aged society. What do you think about that?”

Tezuka spoke of how Black Jack struggled with this dilemma. Simply extending life does not guarantee happiness. But human desire, instinct, is to save the life we see before us. Thus, Dr. Honma muses about the “presumptuousness” of humans.

“What is a doctor’s purpose?” cries Black Jack. (© Tezuka Productions)

The Universality of Tezuka’s Themes

Wrestling with such deep and fundamental themes, Black Jack feels just as relevant today as when Tezuka put it to paper. In fact, his foresight can at times be astonishing. But perhaps most impressive is how it wrestles with adult themes within the framework of a children’s manga. Despite its depth it remains engaging enough for elementary schoolers to pick up and enjoy.

In fact, I myself began reading Black Jack in elementary school. I would peruse issues on the rack at the bookstore (something shoppers are asked not to do today, though at the time, many stores would let it pass). I’d become so engrossed that I would lose track of time, looking up in shock to see it had grown dark outside, then racing home on my bike.

It’s understandable that an adult might want to make a manga about the medical field. But drawing one for children, and making it so engrossing that they get caught up in it, is something that has a great deal of value beyond simple entertainment. I know I am not the only one who feels this way about Tezuka and his work.

Medicine deals with life or death, making it dramatic by nature. Black Jack paved the way for many other medical manga, such as Mafune Kazuo’s Super Doctor K, Yamamoto Kazuki’s God Hand Teru, and Nagai Akira and Nogizaka Tarō’s Iryū (Team Medical Dragon), all of which feature preternaturally skilled doctors.

There are even works that reference it directly, such as Satō Shūhō’s Burakku Jakku ni yoroshiku (Say Hello to Black Jack). And others slip into the realm of science fiction, such as Murakami Motoka’s Jin, which features a doctor who slips back in time to the end of the Edo period (1603–1868).

Initially they followed in the footsteps of their mentor by making characters surgeons (though Say Hello to Black Jack opened with the protagonist as an intern). But thereafter, the medical-manga genre flourished and grew to encompass fields such as disaster medicine, obstetrics, medical education, radiology, and more. Today, 50 years after Black Jack debuted, even child psychologists are getting their own series.

Saving a life may indeed change history. But some manga have that power, too. Black Jack is certainly one of them. I predict it will continue to grow in popularity over the years. Perhaps its eponymous protagonist may attain the status of a Sherlock Holmes, who remains a beloved presence a century after his debut.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image: Scenes from the Tezuka Osamu’s Black Jack Exhibition, held from October 6 to November 6, 2023, at Tokyo City View. © Tezuka Productions.)