Horror at School: The Spread of Scary Stories Among Japanese Children and Teachers

Society Culture Lifestyle Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Why Do Children Like Being Scared?

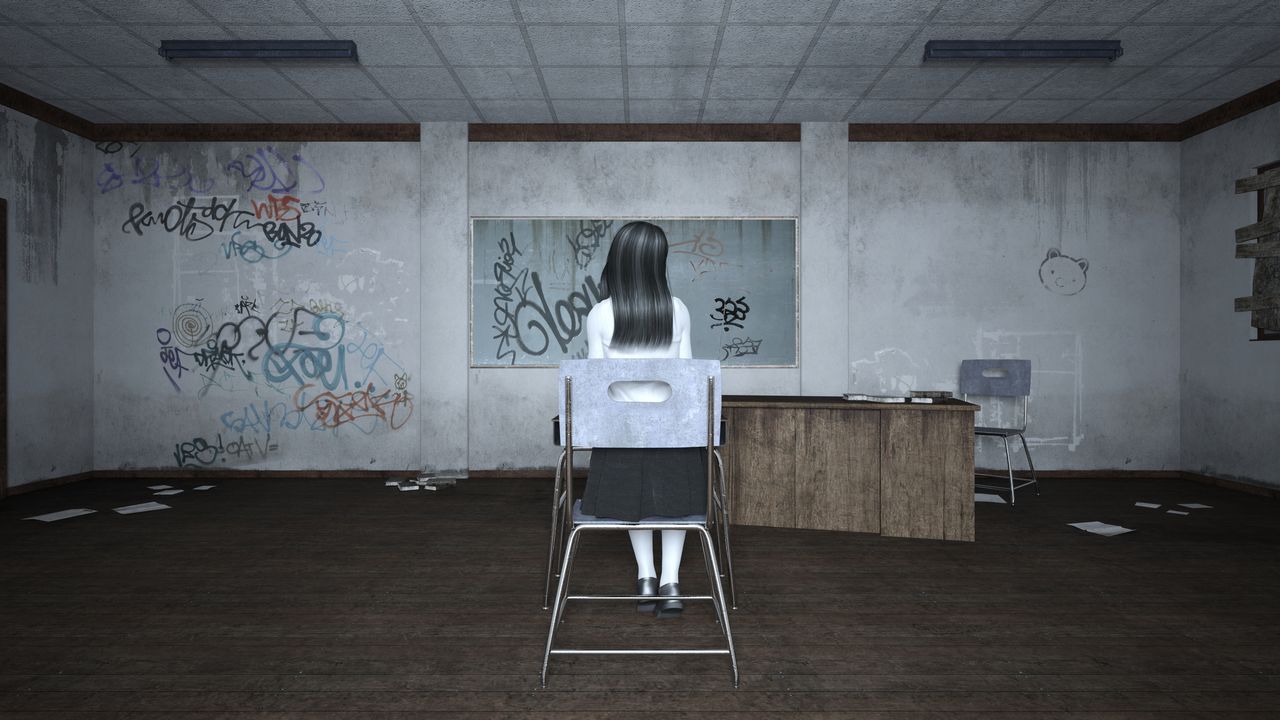

Japanese children enjoy kaidan (scary stories) with a school setting, and these make regular appearances in popular culture. One of the most notorious characters is Toire no Hanako-san (Hanako in the Toilet), who has been famous across Japan since the 1990s.

“My childhood came right in the middle of the school kaidan boom, and there were lots of related books in the school library,” says Yoshioka Kazushi, a specialist in the sociology of education. “I got invited to join a group going to test whether Hanako really was in the toilet or not. And we talked about the Murasaki Babā [Purple Hag], who dressed all in purple and also appeared in the restroom—I have some terrifying memories.”

“Why do children like scary stories?” Yoshioka asks. “Research on children’s culture rarely looks at topics that are considered lowbrow like school kaidan. That’s why I wanted to delve deeper into the meaning these kinds of stories have for children.”

Yoshioka says that kaidan about schools and the areas around them have been passed down since the Education Order of 1872 set in motion the construction of modern schools across Japan. It was only in 1990, however, that the publication of a book by folklorist Tsunemitsu Tōru firmly established the school kaidan genre.

Tsunemitsu was a junior high school teacher, and after classes each day he asked students about the stories and rumors spreading among them. Many of these were kaidan connected to school. Tsunemitsu started publishing a series of books for children introducing Hanako and others, initiating a new craze.

Hanako in the Toilet

In the restroom, a voice asks, “Do you want red paper or blue paper?” Choose red and you die all bloody, choose blue and you perish blue-faced.

This is another common school kaidan. There are many versions, such as one where the voice asks unwary toilet users if they want to wear a red hanten (a kind of jacket)—when they react, their clothes are suddenly drenched in their own blood.

“Stories about hands coming out of the toilet go back a long way,” Yoshioka says. “And there are variations based on the particular variety, with tales of faces either appearing in the water of squat toilets or seen watching from above when people using Western-style toilets look up.”

Apparently, the Hanako story was originally in the “hand from the toilet” pattern. The following is said to have been told in Iwate Prefecture around 1948.

In an elementary school gymnasium restroom, a child went into the third cubicle. “Number Three Hanako,” a voice said, and a white hand emerged from the toilet.

Originally presented as only a disembodied voice, Hanako developed a standard look through appearances in children’s books, manga, and anime, as a girl with an okappa bob, wearing a white shirt and red skirt.

While there are many different stories about what Hanako does, in the classic version, someone knocks three times on the cubicle door, saying “Hanako, let’s play.” She replies, “OK,” and promptly appears and drags the foolish person into the toilet.

Some children who have undertaken a dare add extra details based on their experience. “For example, at the moment they call for Hanako, there might be a great rushing sound of water into the bowl or the creaking of a door, and these elements lead to new variations on the story,” Yoshioka says.

In August 2023, a haunted house event was held at a closed-down elementary school in Aritagawa, Wakayama Prefecture. Participants took on the mission of getting a book from Hanako and carrying it back to the school library. (Courtesy Aritagawa municipal government; poster by children’s book author Yamamoto Takashi)

Setting Conditions

“Once, I looked into the places where kaidan take place in schools. The restroom was the most popular location by far,” Yoshioka says. “After that, it was ordinary classrooms. Dedicated classrooms for subjects like science, music, or art were not that common.

“In folklore studies, the toilet is seen as a boundary space between this world and the next, where there’s a great possibility of encountering supernatural yōkai creatures. Personally, I think that rather than anything extraordinary leading to the appearance of yōkai, it’s the places that children use regularly each day where these creatures manifest themselves.

“Notably, it’s possible to avoid them too. Hanako only appears in a particular cubicle on one floor of a particular building. Restrooms are somewhere children go every day, and also easy places to set conditions. You can relax, knowing it’s safe if you don’t use that cubicle and don’t call her name.

“Classrooms are the same. You can set times when you really shouldn’t go, like midnight, and conditions like the need to position the desks into a particular shape, hold hands in a circle, and chant a spell to summon the yōkai. By setting it up so that nobody encounters yōkai unless they really make the effort to do so, it’s possible to control them.”

Some psychological research suggests that children tell scary stories as a reaction against the restrictive school environment. However, Yoshioka thinks it is simply the case that children, like adults, enjoy being frightened.

“For both adults and children, fear and fun are two sides of the same coin,” he says. “But children have a different way of dealing with their fear, compared with adults who control it through the awareness that kaidan are just fiction. Children have a greater sense of the reality of ghosts and monsters, but they can enjoy their fear through agreed conditions that keep it to a manageable level.

“Thinking that something is there is frightening enough. Sometimes kids might want to test the legend together, and then hold their heads high if nothing happens. ‘We got away with it!’ In that sense, completing a shared ordeal can be a rite of passage that brings people together, and also a communication tool.”

“Island” Friend Groups

From the late 1970s to the 1980s, an urban legend about a kuchisake onna, or “slit-mouthed woman,” spread initially among children attending cram schools before going nationwide. However, Yoshioka thinks it would be hard for such a phenomenon to happen today.

“Children don’t have the same connections now. In class, they tend to group themselves into ‘islands’ of four or five that don’t communicate with each other. Each group may have its own kaidan, but they don’t generally spread.”

He also notes that children don’t have as much time with each other as they used to. “Kids used to stay at elementary school after classes were over until it got late. Now as soon as lessons finish, they’re all sent home to their parents and so on, or they stay in afterschool care. They’re always under the eyes of adults, and they don’t have any time when they just play as children together.”

He adds, “While they have friends in cram school, it’s usual for parents to drop them off and pick them up, so there’s no chance to talk with each other on the way home.”

Self-Censorship

Once, teachers used to tell kaidan to children. Depending on their generation, Japanese people might recall classes pestering their elementary school teachers to “tell a scary story” when there was unfilled class time.

Yoshioka says, however, that since the 1990s craze for school kaidan, teachers have gradually stopped taking on this role. “Once I conducted interviews with teachers aged from their thirties to their fifties. I found that around the year 2000, there was a shift toward self-censorship and not sharing scary stories in the classroom.”

In the 2002 academic year, revised curriculum guidelines incorporated a “period for integrated studies” encouraging students to cultivate individuality as part of an emphasis on giving children room to grow. Yoshioka saw through the interviews though that this yutori, or “relaxed,” education for children was anything but for instructors, who were adapting to the new teaching methods and snowed under with lesson preparation. “Many said that they didn’t have time for chatting about topics like kaidan. There was also more consideration paid to children who didn’t want to hear such stories. Everyone was very aware of what parents and caregivers would think.”

As well as being cautious of the risk of complaints if children could not go to the bathroom alone or were unable to sleep at night, teachers also wanted to maintain class order. “If the class got in a panic, it would be a problem for the lesson that followed,” Yoshioka says. “They seem to have thought that it was best to stay exactly within the time set by the ministry of education and be able to explain the educational meaning of anything if questioned by parents.”

He goes on: “At the same time, providing books with kaidan for children who do want to know about them has become essential to education that considers student needs. Then it’s left to their individual responsibility.”

Yoshioka says that teachers regularly share school kaidan with each other. For example, he heard from one teacher with an affinity for the supernatural about the ghost of a girl called Lily-chan. One deputy head said, “Come here at night, and you can see something white shimmering under that streetlight.” Another teacher told him of an incident that took place when locking up—the door of a room that was rumored to be haunted had slammed shut by itself. Yoshioka comments, “Apparently, it’s common for headteachers or deputy heads to tell new teachers about the school’s ghosts.”

Children and Teachers in Separate Worlds

“My greatest discovery concerning school kaidan is the complete separation between teachers and children,” Yoshioka says. “Teachers talk about them only among themselves, and children enjoy their stories only with each other. Their relationship has been reduced to educating and being educated.”

The days are gone from schools when children held their breath as the teacher recounted a terrifying tale, and they shared their excitement while establishing emotional ties. “School kaidan aren’t culture for children alone,” Yoshioka says. “They can become communication tools that transcend generations. I feel that we should bring back those times when adults and children could have fun together through chatting without a specific educational goal.”

(Originally written by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com and published in Japanese on August 30, 2023. Banner photo © Pixta.)

Related Tags

education toilet children elementary schools teacher urban legend ghost stories